Social Welfare: Interdisciplinary Approach eISSN 2424-3876

2025, vol. 15, pp. 82–105 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/SW.2025.15.5

Mapping Welfare Diversity: A Regional Analysis of Türkiye’s Welfare Regime through Esping-Andersen’s Welfare Regimes Typology

Nurten Ebru Özdemir

Bitlis Eren University, Turkey

E-mail: neozdemir@beu.edu.tr

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3113-2378

https://ror.org/00mm4ys28

Doğa Başar Sarıipek

Kocaeli University, Turkey

E-mail: sariipek@kocaeli.edu.tr

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3525-5199

https://ror.org/0411seq30

Gökçe Cerev

Kocaeli University, Turkey

E-mail: cerevgokce4@gmail.com

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9908-343X

https://ror.org/0411seq30

Abdülkadir Akturan

Piri Reis University, Turkey

E-mail: aakturan@pirireis.edu.tr

https://orcid.org/0009-0008-9107-0333

https://ror.org/02eq60031

----------------------------------------------------------

This study was supported by the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey under the TÜBİTAK 1002B project and produced within the scope of a doctoral thesis.

----------------------------------------------------------

Abstract. This study develops a comprehensive regional welfare map of Türkiye by using Esping-Andersen’s welfare typologies with the objective to analyze regional variations in welfare policies. By focusing on poverty and unemployment as key indicators, the research categorizes Türkiye’s welfare systems at both macro and micro levels, offering valuable insights for shaping future social welfare policies. A total of 243 semi-structured interviews were conducted across all 81 provinces with Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) selected based on their involvement in welfare-related activities. The data, analyzed by using Maxqda software, reveals that Turkey exhibits a hybrid welfare system, incorporating liberal, conservative, and social democratic elements, with significant regional disparities. NGOs play a critical role in bridging gaps in the State welfare provision, particularly in regions with limited State intervention. Supported by the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey (TÜBİTAK), this study makes a significant contribution to the welfare typology literature and provides practical insights for reducing regional inequalities.

Keywords: Regional welfare map, poverty, unemployment, welfare typologies, welfare regime in Türkiye.

Introduction

Welfare policies form a central pillar of social policy, by virtue of shaping the structure and functioning of societies by addressing key issues such as poverty, unemployment, and social inequality. These policies are not only mechanisms of economic redistribution, but they also reflect the ideological underpinnings of State governance. Welfare is thus more than just an economic issue; it is a socio-political framework which influences every aspect of a country’s development. Since the outbreak of Industrial Revolution, welfare systems have become integral to ensuring social stability and addressing the disruptions caused by economic modernization, including the rise of income inequality and the shifting dynamics of labor markets.

The Esping-Andersen’s welfare regimes typology – liberal, conservative, and social democratic – provides a robust framework for analyzing how different countries are approaching welfare provision. This typology is traditionally applied at the national level, categorizing states based on the degree to which the market, state, NGOs, or family plays a role in welfare distribution. However, such a national focus often overlooks the significant regional variations within countries, especially those with diverse social, economic, and political landscapes. Türkiye, with its distinct regional disparities and unique socio-political history, represents an important case for studying welfare at the regional level. Table 1, which provides a classification of regional units in Türkiye, serves as the foundation for this study by delineating the territorial divisions that shape the welfare dynamics across the country. Given its geographic position straddling Europe and Asia, Türkiye’s welfare system is influenced by a combination of Eastern and Western welfare traditions, thereby making it a compelling subject for examining its regional welfare typologies.

The objective of this study is to create a comprehensive regional welfare map of Türkiye by applying the Esping-Andersen’s welfare regimes typology to different regions, as detailed in Tables 2 through 13. A particular focus is placed on the indicators of poverty and unemployment, as these two measures offer tangible insights into the effectiveness of the social welfare policies and provide a basis for comparing welfare outcomes across different regions. While poverty and unemployment are prevalent across Türkiye, they manifest in distinct ways across different welfare regime regions, as detailed in Tables 2 through 13, each of which presents the welfare structure of a specific region.

This research is pioneering in the sense that it provides the first in-depth regional analysis of welfare in Türkiye, going beyond national categorizations to explore how welfare systems operate on a micro level. Supported by the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey (TÜBİTAK), the study employs a qualitative research approach to capture the nuanced ways in which welfare policies are implemented and experienced across Türkiye’s diverse regions. Semi-structured interviews were conducted across all 81 provinces, involving 243 representatives from the relevant institutions, including Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), whose activities in each welfare regime region are explored in Tables 2 through 13. These organizations were selected based on their type of activity, scope, the number of beneficiaries, and their involvement in welfare-related policies, thus providing a rich source of qualitative data.

The analysis, conducted by using Maxqda software, allowed for the identification of regional welfare typologies, highlighting the variations in welfare regimes across Türkiye’s subregions. Tables 2 through 13 present a detailed examination of each region’s welfare regime, while illustrating the prevalence of State, market, and NGO involvement in welfare provision. For example, Table 2 (Istanbul Subregion) and Table 3 (Western Marmara) highlight the significant role of market-driven welfare, whereas Tables 4 and 5 (Aegean and Eastern Marmara) show a mixed welfare model with substantial State intervention. Similarly, Tables 6 through 9 (Western Anatolia, Mediterranean, Central Anatolia, and Western Black Sea) reveal variations in family-based and NGO-driven welfare approaches.

Furthermore, the study examines how poverty and unemployment, as key indicators, vary across different regions and the extent to which the currently existing welfare policies are addressing these issues. Tables 4 through 13 provide an in-depth look at regional welfare disparities, illustrating how socio-economic factors shape welfare distribution. The classification of regions according to the Esping-Andersen’s typology, outlined in these tables, allows for a structured comparison of welfare outcomes across Türkiye.

The role of different welfare providers – the market, the State, and the family – is also assessed through the comparative analysis of different regional welfare models presented in Tables 2 through 13. Additionally, detailed case studies of specific provinces, captured within these tables, further illustrate the nuances of welfare implementation at the local level. Finally, the comparative analysis summarized in Table 13 (Southeast Anatolia) highlights the overall successes and challenges of different welfare models in Türkiye, offering critical insights for both academia and policymakers.

By integrating regional analysis into welfare state research, this study provides a framework for developing targeted welfare policies which take into account the specific needs and challenges of different regions. The findings contribute not only to the academic literature on welfare state typologies but also offer practical guidance for policymakers seeking to address regional disparities in the social welfare provision.

Theoretical Background

Social policy practices play a crucial role within the framework of welfare and welfare typologies. Their main aim is to mitigate social inequalities, support disadvantaged groups, and create mechanisms which would guarantee the fulfillment of fundamental needs for all individuals. One of the key objectives for states is to develop and implement effective policies that enhance welfare, which is a central concern in the social policy (Şenkal, 2024; Küçükoba, 2022). To improve societal welfare, it is essential to first accurately assess the current level of welfare, and then measure the progress achieved after implementing these policies. Therefore, the success of welfare policies is closely tied to the precise measurement of welfare. This underscores the importance of selecting the appropriate indicators for evaluating welfare. Poverty and unemployment statistics are widely recognized as two critical indicators in this regard (Koray, 2005). These issues have historically been, and still continue to be, major challenges for both developed and developing countries, presenting significant risks that demand attention.

Poverty is a conceptually multidimensional issue widely discussed in the literature. As a critical aspect of welfare policies, poverty must be evaluated from various angles, including the differing development levels of countries, the diversity of social resources and needs, the impact of time and place, and the variations in expectations and consumption habits. The lack of a universal consensus on the definition of poverty further complicates the development of a single, all-encompassing definition. Historically, poverty was first understood through the lens of accessibility and deprivation of material resources. This perspective primarily framed poverty as the inability to meet basic needs such as nutrition, shelter, and physiological necessities, which are essential for survival (Rowntree, 1901). This economic interpretation of poverty emphasized the insufficiency of income to cover these minimum needs (Lewis, 1966).

However, as perceptions and contributing factors evolved over time, the concept of poverty expanded to include an individual’s ability to meet the standards of the society in which they live. Thus, poverty began to be assessed by using not only material but also subjective data. Today, poverty is defined in broader terms, by encompassing social, cultural, technological, and other criteria which vary across different quantitative and qualitative dimensions (Zimmermann and Graziano, 2020; Benjamin, 2006). This evolution has led to the emergence of two main approaches to defining poverty: the one-dimensional view, which focuses on per capita income and expenditures by using a single indicator, and the multidimensional view, which considers not only economic factors but also social, cultural, and political elements (Padda and Hameed, 2018).

The multidimensional approach to poverty is crucial for the development of social policies which address not just economic growth but also social development. This broader perspective defines poverty more generally as the lack of sufficient income to maintain a sustainable standard of living, or the deprivation of essential physiological needs such as food, shelter, water, and more.

Unemployment is widely recognized as the second crucial indicator for measuring welfare. Historically and in the present day, the most significant impact of unemployment remains the individual’s inability to meet their needs due to a lack of income. The industrial revolution brought about profound changes, transforming unemployment into a chronic issue with global implications, and leading to its entrenchment as a persistent problem. Unemployment is not only an economic challenge but also a social and psychological one, affecting both individuals and society at large due to various factors. As such, unemployment is intrinsically linked to welfare. The adverse effects of unemployment are now felt across entire societies, making it a global issue which concerns all nations (Uyar, 2008).

Poverty and unemployment are central concerns in welfare policies, particularly within the realm of social policy, and are crucial to the overall well-being of society. Welfare policies address these issues while also influencing the reshaping of other domains such as economic policies, tradition, culture, politics, and broader social policies. The scope and implementation of welfare policies vary based on a country’s level of development, as well as on its economic, political, and cultural structures. Despite these variations, the common objective of welfare policies across states is to enhance the welfare of both individuals and society. In this context, welfare policies are often closely associated with the concept of the social state, and they aim to meet individuals’ basic needs, reduce poverty and social exclusion, and promote equality and justice. To achieve these goals, states employ a wide range of social policy instruments, including social insurance, social security, cash and in-kind benefits, and subsidies (Briggs, 1961).

Within the realm of social policy, states have taken on various roles in their pursuit to enhance the societal welfare. Initially, states acted as passive observers in welfare policies, but, over time, they adopted a more interventionist stance, and ended up becoming central to the implementation of these policies (Roosma and Van Oorschot, 2020; Yay, 2020). The welfare state model that many states have embraced integrates a combination of social policies, social expenditures, institutional arrangements, and regulatory frameworks, all aimed at improving welfare outcomes (Esping-Andersen, 1991).

Those states which adopt welfare policies have been classified in various ways based on the methods they employ (Mishra, 1997; Flora, 1986). Among these classifications, Esping-Andersen’s “Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism” (1990) stands out as a seminal framework in the study of the welfare state typologies. According to Esping-Andersen (1990; 1999), welfare state regimes are characterized by legal and organizational complexities. He defines them as systematic, legal, and organizational functions that regulate the interactions within the state-economy-household triangle, shaped by historical development (Kaariainen and Lehtonen, 2006).

Esping-Andersen’s ideal welfare state typology possess a holistic structure that enables welfare states to develop policies addressing the challenges and risks individuals may encounter throughout their lives. He categorizes welfare states into three distinct typologies: Liberal, Social Democratic, and Corporatist/Conservative, each reflecting different welfare policies practiced globally to varying degrees (Esping-Andersen, 1990). The diversity of these typologies is rooted in the roles of the market, state, and family. In Esping-Andersen’s framework, the market is central to the Liberal model, the family to the Conservative model, and the state to the Social Democratic model.

Esping-Andersen’s objective in developing this welfare regimes typology was to create a mid-level theory of welfare systems which would avoid both theological and functionalist approaches, which would emphasize commonalities and convergence, as well as post-modern perspectives, and which would focus on national and sub-national uniqueness (Gough, 2001; Frericks, Gurín, and Höppner, 2023). In the light of these approaches, the cultural, structural, and institutional characteristics of states are crucial in shaping welfare regimes. The overarching goals of welfare policies are to maximize the standards of equality and social citizenship, to provide basic income protection to citizens, and to minimize social exclusion. Consequently, welfare policies are significant both at the national level and within regions of a country, where distinct welfare regimes may emerge based on regional characteristics.

Research Methodology and Application

Purpose and Importance of the Research

In Türkiye, unemployment and poverty are not treated as issues necessitating direct political intervention, largely due to the country’s adopted welfare typologies, which incorporate various mechanisms to prevent these problems from becoming chronic (Buğra and Keyder, 2003: 16). This study aims to map the regional distribution of welfare typologies, identify the welfare models prevalent in different regions, and analyze their role in shaping welfare state structures. By utilizing unemployment and poverty indicators, this research contributes to the social policy literature by offering a regional assessment of the welfare typologies. Therefore, this study aims to create a regional welfare map of Türkiye by using Esping-Andersen’s Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism as a framework. While the currently existing research on welfare regimes generally focuses on national-level evaluations, this study uniquely examines and interprets welfare regimes at the regional level within a single country, specifically, Türkiye. This makes the study a pioneering contribution to the literature. Additionally, it holds significant value in guiding micro-level welfare policies in Türkiye, with a focus on improving welfare through unemployment and poverty indicators at the regional level, and fostering advancements in the social policy.

The fieldwork for this study was conducted in collaboration with NGOs which play a crucial role in the implementation of welfare policies. The research involved NGOs in each province of Türkiye, by employing an inductive approach serving the objective to explore the subject comprehensively across the country’s administrative structure.

Scope of the Research

The research encompasses Türkiye as a whole, with an applied field study conducted across the entire country. Specifically, the study was implemented in all 81 provinces, thus reflecting Türkiye’s administrative divisions. To delineate the scope and limitations of the research, the study utilized the three sub-levels of the Statistical Classification of Territorial Units (NUTS) provided by the Turkish Statistical Institute. This classification includes 12 regions at Level 1, 26 regions at Level 2, and 81 provinces at Level 3. The scope of this study is primarily limited to the 26 regions classified under NUTS Level 2 in Türkiye. This limitation is intended to structure Türkiye’s welfare map into 12 broader regions, considering regional and provincial development levels within the three-tiered NUTS classification. This approach enhances the effectiveness of the assessment. Under NUTS Level 1, Türkiye is divided into 26 regions, and, in order to ensure homogeneity among the subregions, factors such as the population structure and the metropolitan status, have been considered. Within this framework, welfare typologies at the subregional level have also been analyzed with the objective to provide a more comprehensive evaluation.

In this research, the data were analyzed across the 81 provinces of Türkiye, categorized into 26 regions at Level 2 according to the NUTS classification of the Turkish Statistical Institute. This classification ensured uniformity within sub-regions, and allowed for a balanced interpretation of economic, cultural, and social differences, particularly considering the population structure of each province. The research facilitated an assessment initially of the 26 regions, and, subsequently of Türkiye as a whole, by using an inductive approach. Fieldwork for the study involved conducting face-to-face interviews with 243 officials from NGOs, with three interviews conducted per province. The field study was carried out between September 2022 and April 2023.

Research Method and Question

This study employed a mixed research method, integrating both quantitative and qualitative approaches. The quantitative component utilized numerical data from official statistical institutions, specifically, the Turkish Statistical Institute, with the objective to provide a foundational framework of poverty and unemployment data. The qualitative component involved a semi-structured interview form, which had been developed in advance by using scientific methods.

To define the research problem in the qualitative segment, questions from the ‘role of the State’ scale of the International Social Research Programme (ISSP, 2006) were adapted. The semi-structured interview questions were initially reviewed by language experts, and subsequently finalized based on feedback from academic experts in the field. The research questions addressed in the semi-structured interviews are as follows:

• As a humanitarian aid organization, what are your attitudes towards providing employment opportunities for citizens seeking work?

• What is your stance on supporting health insurance for sick citizens?

• What assistance do you provide to ensure a minimum standard of living for elderly individuals?

• Do you offer a minimum level of income to unemployed citizens?

• How do you address income inequality between high-income and low-income citizens?

• Do you provide financial support for university students from low-income families? If so, what are the criteria and amounts?

• Do you assist individuals who are unable to acquire housing with their own resources?

• How do disparities in the prices of goods and services and wages in the labor market impact social assistance financially?

• What in-kind and cash aid do you provide to disabled individuals to ensure a minimum standard of living?

• Do you ensure a minimum standard of living for the children of low-income families, and if so, at what educational levels and ages?

Validity, Reliability and Ethical Approval

In scientific research, the credibility of the results largely hinges on the validity and reliability of the study. While validity and reliability are crucial, Gruba and Lincoln emphasized the importance of credibility over these traditional metrics in qualitative research (Houser, 2015; Merriam, 2013; Whittemore, Chase, and Mandle, 2001).

In qualitative research, ensuring credibility involves several factors beyond just validity and reliability. These include the appropriateness of the research conditions, meticulous pre-planning of the interview questions, thorough documentation of the research process, detailed description of the data, and the selection of a sufficiently large sample (Başkale, 2016). The primary focus in qualitative research is to explore and interpret the existence and meaning of the phenomena under consideration. Validity in qualitative research is assessed through the comprehensive and detailed reporting of data and the clarity with which the researcher explains how the conclusions were reached (Yıldırım and Şimşek, 2011).

In qualitative research, validity is defined as the researcher’s ability to observe and interpret the phenomenon as it exists, with minimal bias (Kirk and Miller, 1986). Reliability, on the other hand, is characterized by the researcher’s diligence in obtaining accurate information, which is essential for the scientific integrity of the research, including data collection and analysis.

To ensure validity and reliability in this study, input was sought from a panel of experts: four in social work, three in social policy, and three in labor economics and industrial relations. This expert feedback was used to evaluate the research questions based on their relevance, significance, and methodological alignment. Initially, a pool of 15 questions was reviewed by experts, resulting in the removal of five questions that fell below a 50% approval threshold. This process led to the creation of a refined 10-question semi-structured interview form.

Ethical approval for the research was granted by the Kocaeli University Institute of Social Sciences Ethics Committee under permission number 155728, dated 2021. Additionally, the study received support from the TÜBİTAK 1002 program.

Population and Sample of the Research

The primary objective of qualitative research is not to generalize findings across a specific population, but rather to achieve a comprehensive understanding of a phenomenon by capturing its diversity, richness, contradictions, and variations (Goetz and LeCompte, 1984). Qualitative research is inherently flexible, and this flexibility is evident throughout all stages of the research process. This characteristic allows for the simultaneous use of multiple sampling methods when making sampling decisions (Yıldırım and Şimşek, 2011). In this study, various purposive sampling techniques were employed to leverage the benefits of this flexibility and to enhance the depth of the research findings.

This research aims to conduct an in-depth examination of the phenomena of unemployment, poverty, and welfare, which are crucial aspects of social policy practices. To achieve this, it is essential that the study should not only cover a broad sample but also include participants who are well-versed and knowledgeable about these issues, thereby allowing for a thorough investigation (Islamoğlu and Alnıaçık, 2016). The study encompasses all 81 provinces within Türkiye’s administrative structure. The sample, intended to represent this entire population, includes 243 NGOs, with three organizations selected from each of the 81 provinces, within the framework of the NUTS 2 level (26 sub-regions) as per the scope and limitations of the research.

Evaluation of Research Findings

In the initial stage of coding the research data, the notes taken during face-to-face interviews were transcribed into Microsoft Word and underwent a preliminary evaluation. Following this evaluation, the data were imported into the Maxqda qualitative data analysis software according to the framework established by the researchers. Variables were assigned within the Maxqda program, and the coding process commenced. Upon the completion of the coding, the results were analyzed and interpreted within the defined scope of the study.

In this study, the data were analyzed across all 81 provinces within their respective sub-regions. During the evaluation phase, NGOs were coded with the letter ‘S’, and those interviewed in each province were identified as ‘S1’, ‘S2’, ‘S3’, in the coding system. The analysis was conducted by using the criteria established by Esping-Andersen’s Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. The criteria for Esping-Andersen’s welfare regimes’ classification are as follows:

• Liberal Welfare Regime: In this model, the market is the primary provider of welfare, with the State playing a compensatory role in addressing social issues. The State intervenes only as a last resort and provides need-based assistance financed through taxation. Access to aid is often bureaucratically intensive and procedurally complex.

• Conservative Welfare Regime: This model emphasizes the role of the State and prioritizes the family unit in the welfare system, while rejecting the market’s primary role. Social assistance is rooted in solidarity, and the preservation of traditional family structures is encouraged. The State complements the family institution when it falls short.

• Social Democratic Welfare Regime: This model features universal welfare policies with a focus on achieving full employment. The State is central to welfare provision, delivering social assistance through tax revenues. It promotes high social solidarity, egalitarianism, and comprehensive support services, particularly for disadvantaged groups.

Table 1.

Welfare regime of TR1 Istanbul Subregion

|

Theme |

Participants |

f |

|

TR100 İstanbul |

||

|

Liberal Welfare Regime |

S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S7, S9 |

7 |

|

Social Democratic Welfare Regime |

S1, S2, S3, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

7 |

|

Conservative Welfare Regime |

0 |

|

|

Total |

14 |

* The responses provided by participants revealed multiple themes.

In Türkiye’s administrative structure, the Istanbul Sub-region is identified as the first level. Analysis of interviews conducted with NGOs in this region highlights the prominence of both liberal and social democratic welfare regimes. As the most populous city in Türkiye, Istanbul plays a pivotal role in shaping the nation’s social, cultural, and economic landscape. Notably, the conservative welfare regime was absent from the findings for Istanbul. NGOs in this region primarily reported providing assistance to individuals unable to receive State support in cases of poverty. Regarding unemployment, these organizations focus on enhancing individuals’ employability rather than directly facilitating job placement.

Table 2.

Welfare regime of TR2 Western Marmara region

|

Theme |

Participants (TR2 Western Marmara Region) |

f |

||||

|

TR211 Tekirdağ |

TR212 Edirne |

TR213 Kırklareli |

TR221 Balıkesir |

TR222 Çanakkale |

||

|

Liberal Welfare Regime |

S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S7, S10 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7, S9 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7 |

28 |

|

Social Democratic Welfare Regime |

S2, S3, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S1, S2, S3, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S1, S3, S6, S9, S10 |

S1, S2, S3, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S3, S6, S9, S10 |

29 |

|

Conservative Welfare Regime |

S4, S6 |

S4, |

S4, S5 |

S4 |

S4, |

7 |

|

Total |

15 |

13 |

12 |

14 |

10 |

64 |

* The responses provided by participants revealed multiple themes.

Based on the evaluation of interviews with 15 NGOs across the Tekirdağ, Edirne, Kırklareli, Balıkesir, and Çanakkale provinces in the TR2 West region, it has been observed that social democratic and liberal welfare regimes are more prevalent, while conservative welfare provisions are present only to a limited extent. The welfare policies in this region are primarily influenced by market forces, with NGOs reporting that they provide partial assistance to those individuals and families who do not receive State aid. In terms of employment, these organizations focus more on intermediary activities to facilitate job placement instead of directly securing employment opportunities.

Interviews with 24 NGOs in the TR3 Aegean Region, encompassing the provinces of İzmir, Aydın, Denizli, Muğla, Manisa, Afyon, Kütahya, and Uşak, reveal a predominance of both liberal and social democratic welfare regimes. In this region, welfare policies are predominantly aligned with the social democratic welfare regime. NGOs serve either as complementary agents to the State, or directly on behalf of the State. In the realm of employment policies, there is a notable emphasis on activities aimed at directly integrating individuals into the labor force.

Table 3.

Welfare regime of TR3 Aegean region

|

Theme |

Participants (TR3 Aegean Region) |

f |

|||||||

|

TR310 İzmir |

TR321 Aydın |

TR322 Denizli |

TR323 Muğla |

TR331 Manisa |

TR332 Afyon |

TR333 Kütahya |

TR334 Uşak |

||

|

Liberal Welfare Regime |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7, S9 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7 |

S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S7, S9 |

S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S7, S9 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7, S9 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7 |

S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S7 |

47 |

|

Social Democratic Welfare Regime |

S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S3, S5, S6, S7, S9, S10 |

S1, S2, S3, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S1, S2, S3, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S2, S3, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S1, S2, S3, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S1, S2, S3, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S1, S2, S3, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

55 |

|

Conservative Welfare Regime |

- |

S4, |

S4, |

- |

- |

S4 |

S4 |

S4, |

5 |

|

Total |

14 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

13 |

14 |

13 |

14 |

107 |

* The responses provided by participants revealed multiple themes.

Table 4.

Welfare regime of TR4 Eastern Marmara region

|

Theme |

Participants (TR4 Eastern Marmara Region) |

f |

|||||||

|

TR411 Bursa |

TR412 Eskişehir |

TR413 Bilecik |

TR421 Kocaeli |

TR422 Sakarya |

TR423 Düzce |

TR424 Bolu |

TR425 Yalova |

||

|

Liberal Welfare Regime |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S6, S7, S9 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S6, S7, S9 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7, S9 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7, S9 |

S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S7, S9 |

48 |

|

Social Democratic Welfare Regime |

S2, S3, S5, S6, S7, S9, S10 |

S3, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S3, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S3, S4, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S2, S3, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S2, S3, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S2, S3, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S3, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

46 |

|

Conservative Welfare Regime |

S4, S5, S10 |

S4 |

S4 |

- |

S4 |

- |

- |

S4 |

7 |

|

Total |

17 |

13 |

11 |

11 |

13 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

101 |

* The responses provided by participants revealed multiple themes.

Interviews with 24 NGOs in the TR4 Eastern Marmara Region, including the provinces of Bursa, Eskişehir, Bilecik, Kocaeli, Sakarya, Yalova, Düzce, and Bolu, reveal a predominance of the liberal welfare approach, with the social democratic approach being the second most prevalent regime. The conservative approach is observed at a minimal level in this region. Social assistance, as well as poverty and unemployment support, are predominantly influenced by state-oriented policies. NGOs in this region tend to adopt complementary approaches that support and enhance the State’s efforts.

Table 5.

Welfare regime of TR5 Western Anatolia region

|

Theme |

Participants (TR5 Western Anatolia Region) |

f |

||

|

TR511 Ankara |

TR521 Konya |

TR522 Karaman |

||

|

Liberal Welfare Regime |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7, S9 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S6, S7, S9 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7, |

18 |

|

Social Democratic Welfare Regime |

S3, S4, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S3, S4, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S1, S2, S3, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

19 |

|

Conservative Welfare Regime |

- |

S3, S5 |

S4 |

3 |

|

Total |

12 |

15 |

13 |

40 |

* The responses provided by participants revealed multiple themes.

Interviews with nine NGOs in the TR5 Western Anatolia Region, specifically, in the provinces of Ankara, Konya, and Karaman, highlight the predominance of social democratic and liberal welfare regimes, with conservative welfare provisions being observed to a limited extent. Notably, the presence of the social democratic welfare regime in regions such as Konya and Karaman, which are predominantly conservative, underscores the significant role of the State in welfare policies. This finding reflects citizens’ expectations that welfare practices should primarily be managed by the State. In this context, NGOs in the region predominantly engage in activities that complement the State’s initiatives.

Interviews with 24 NGOs across the provinces of Antalya, Isparta, Burdur, Adana, Mersin, Hatay, Kahramanmaraş, and Osmaniye in the TR6 Mediterranean Region reveal that the social democratic welfare regime is predominant in the area. Additionally, the liberal welfare regime also plays a significant role, while the conservative welfare regime is present only to a limited extent. NGOs in this region primarily function as intermediaries, facilitating the distribution of State-sponsored poverty and unemployment aid. Consequently, most welfare assistance in this region is State-funded.

Table 6.

Welfare regime of TR6 Mediterranean region

|

Theme |

Participants (TR6 Mediterranean Region) |

f |

|||||||

|

TR611 Antalya |

TR612 Isparta |

TR613 Burdur |

TR621 Adana |

TR622 Mersin |

TR631 Hatay |

TR632 K. Maraş |

TR633 Osmaniye |

||

|

Liberal Welfare Regime |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7, S9 |

S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S7, S9, S10 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7, S9 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S6, S7 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7, S9 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7 |

47 |

|

Social Democratic Welfare Regime |

S1, S3, S4, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S1, S2, S3, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S2, S3, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S3, S4, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S1, S3, S4, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S1, S3, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S1, S3, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S1, S3, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

51 |

|

Conservative Welfare Regime |

S3 |

- |

S4 |

S5 |

S4 |

- |

S4 |

S4, S5 |

7 |

|

Total |

14 |

15 |

12 |

12 |

14 |

12 |

13 |

13 |

105 |

* The responses provided by participants revealed multiple themes.

Table 7.

Welfare regime of TR7 Central Anatolia region

|

Theme |

Participants (TR7 Central Anatolia Region) |

f |

|||||||

|

TR711 Kırıkkale |

TR712 Aksaray |

TR713 Niğde |

TR714 Nevşehir |

TR715 Kırşehir |

TR721 Kayseri |

TR722 Sivas |

TR723 Yozgat |

||

|

Liberal Welfare Regime |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7, S9 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7 |

S2, S4, S5, S7 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S6, S7 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7, S9 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7 |

42 |

|

Social Democratic Welfare Regime |

S3, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S3, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S3, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S3, S6, S9, S10 |

S3, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S3, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S1, S2, S3, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S3, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

41 |

|

Conservative Welfare Regime |

S4, S5 |

S5 |

S4 |

S1, S5 |

S4 |

S4 |

S4, S5 |

S4, S5 |

12 |

|

Total |

13 |

11 |

11 |

10 |

12 |

12 |

14 |

12 |

95 |

* The responses provided by participants revealed multiple themes.

Based on interviews with 24 NGOs across Kırıkkale, Aksaray, Niğde, Nevşehir, Kırşehir, Kayseri, Sivas, and Yozgat provinces in the TR7 Central Anatolia Region, it has been determined that welfare policies predominantly align with both the social democratic and liberal welfare regimes. Additionally, it was observed that the traditional protective family structure remains partially intact, resulting in a limited application of the conservative welfare regime in the region.

Table 8.

Welfare regime of TR8 Western Black Sea region

|

Theme |

Participants (TR8 Western Black Sea Region) |

f |

|||||||||

|

TR811 Zonguldak |

TR812 Karabük |

TR813 Bartın |

TR821 Kastamonu |

TR822 Çankırı |

TR823 Sinop |

TR831 Samsun |

TR832 Tokat |

TR833 Çorum |

TR834 Amasya |

||

|

Liberal Welfare Regime |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7, S9 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7, S9 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7, S9 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7, S9 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S6, S7, S9 |

S1, S4, S5, S6, S7 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7, S9 |

57 |

|

Social Democratic Welfare Regime |

S3, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S3, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S3, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S1, S3, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S2, S3, S4, S5, S6, S10 |

S1, S2, S3, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S1, S3, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S1, S3, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S1, S2, S3, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S1, S3, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

59 |

|

Conservative Welfare Regime |

S4 |

- |

S5 |

S4 |

S3, S5 |

S4, S5 |

S3, S4, S5 |

S4, S5 |

S3, S4, S5 |

S3, S4, S5 |

18 |

|

Total |

11 |

11 |

11 |

13 |

14 |

14 |

15 |

15 |

15 |

15 |

134 |

* The responses provided by participants revealed multiple themes.

Interviews with 30 NGOs across Zonguldak, Karabük, Bartın, Çankırı, Amasya, Kastamonu, Samsun, Çorum, Tokat, and Sinop provinces in the TR8 Western Black Sea Region revealed that the liberal welfare regime is predominant. The organizations indicated that welfare policies in this region largely operate within the market conditions, with the State playing a limited role. Following the liberal welfare regime, the social democratic welfare regime also features prominently, while the conservative welfare regime is observed but at a relatively minimal level.

Table 9.

Welfare regime of TR9 Eastern Black Sea region

|

Theme |

Participants (TR9 Eastern Black Sea Region) |

f |

|||||

|

TR901 Trabzon |

TR902 Ordu |

TR903 Giresun |

TR904 Rize |

TR905 |

TR906 Gümüşhane |

||

|

Liberal Welfare Regime |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S6, S7 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7, S9 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7, S9 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S6, S7 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7 |

34 |

|

Social Democratic Welfare Regime |

S1, S3, S5, S9, S10 |

S1, S3, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S1, S3, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S1, S3, S5, S6, S7, S9, S10 |

S1, S3, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S1, S3, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

36 |

|

Conservative Welfare Regime |

S3, S4 |

S4 |

S4 |

S3, S4, S5 |

- |

S4 |

8 |

|

Total |

13 |

12 |

13 |

16 |

12 |

12 |

78 |

* The responses provided by participants revealed multiple themes.

Interviews with 18 NGOs across Trabzon, Ordu, Giresun, Rize, Artvin, and Gümüşhane provinces in the TR9 Eastern Black Sea Region revealed that the social democratic welfare regime is predominant. Additionally, the liberal welfare regime also plays a significant role in the region. The findings indicate that State aid is central to welfre policies in this area, with NGOs primarily adopting supportive roles.

Table 10.

Welfare regime of TRA Northeast Anatolia region

|

Theme |

Participants (TRA Northeast Anatolia Region) |

f |

||||||

|

TRA11 Erzurum |

TRA12 Erzincan |

TRA12 Bayburt |

TRA21 Ağrı |

TRA22 Kars |

TRA23 Iğdır |

TRA24 Ardahan |

||

|

Liberal Welfare Regime |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7 |

S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S7, S9 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7, S9 |

S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S7 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7, S9 |

S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S7, S9 |

42 |

|

Social Democratic Welfare Regime |

S2, S3, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S1, S3, S4, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S1, S2, S3, S4, S6, S9, S10 |

S2, S3, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S2, S3, S5, S6, S7, S9, S10 |

S2, S3, S4, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S2, S3, S6, S9, S10 |

45 |

|

Conservative Welfare Regime |

S4 |

- |

- |

S3 |

S3, S4 |

S3, S10 |

S4 |

7 |

|

Total |

12 |

12 |

14 |

13 |

15 |

15 |

13 |

94 |

* The responses provided by participants revealed multiple themes.

Interviews with 21 NGOs in Erzurum, Erzincan, Bayburt, Ağrı, Kars, Iğdır, and Ardahan provinces within the TRA Northeast Anatolia Region revealed that the social democratic welfare regime is predominant. Additionally, the liberal welfare regime is also significant in the region, whereas the conservative welfare provisions are observed to a limited extent.

Table 11.

Welfare regime of TRB Middle East Anatolia region

|

Theme |

Participants (TRB Middle East Anatolia Region) |

f |

|||||||

|

TRB11 Malatya |

TRB12 Elazığ |

TRB13 Bingöl |

TRB14 Tunceli |

TRB21 Van |

TRB22 Muş |

TRB23 Bitlis |

TRB24 Hakkâri |

||

|

Liberal Welfare Regime |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7 |

S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S7, S9 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7, S9 |

S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S7, S9 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S6, S7 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7, S9 |

S1, S2, S3, S5, S7, S9 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7 |

48 |

|

Social Democratic Welfare Regime |

S2, S3, S5, S6, S7, S9, S10 |

S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S2, S3, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S2, S3, S5, S6, S10 |

S2, S3, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S1, S3, S4, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S1, S3, S5, S6, S7, S9, S10 |

S1, S2, S3, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

53 |

|

Conservative Welfare Regime |

S3, S4 |

S3, S4, S5 |

S3, S4, S5, S7 |

S4 |

S4, S10 |

S3, S4, S5 |

S4, S5 |

S4, S10 |

19 |

|

Total |

14 |

18 |

16 |

13 |

14 |

16 |

15 |

14 |

120 |

* The responses provided by participants revealed multiple themes.

Interviews with 24 NGOs across the provinces of Malatya, Elazığ, Bingöl, Tunceli, Van, Muş, Bitlis, and Hakkâri in the TRB Middle East Anatolia Region reveal that the social democratic welfare regime is predominant. Notably, this region exhibits a higher level of conservative welfare provisions compared to others. In this context, the family institution, while secondary to the State, plays a significant role in the implementation of welfare policies. NGOs in this region offer welfare-enhancing support in areas where the State’s provision is insufficient, and the family institution serves as a crucial complementary entity.

Interviews conducted with 27 NGOs in the provinces of Gaziantep, Adıyaman, Kilis, Şanlıurfa, Diyarbakır, Mardin, Batman, Şırnak, and Siirt within the TRC Southeastern Anatolia Region reveal that social democratic welfare practices are predominant. Additionally, the liberal welfare regime is also present in the region. Although the traditional welfare regime is observed, it appears at a limited level, and is significantly influenced by the region’s traditional family structure.

Table 12.

Welfare regime of TRC Southeast Anatolia region

|

Theme |

Participants (TRC Southeast Anatolia Region) |

f |

||||||||

|

TRC11 Gaziantep |

TRC12 Adıyaman |

TRC13 Kilis |

TRC21 Şanlıurfa |

TRC22 Diyarbakır |

TRC31 Mardin |

TRC32 Batman |

TRC33 Şırnak |

TRC34 Siirt |

||

|

Liberal Welfare Regime |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7, S9 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7, S9 |

S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S7 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7, S9 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7, S9 |

S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S7 |

S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S7, S10 |

S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S7, S9 |

S1, S2, S4, S5, S7, S9 |

56 |

|

Social Democratic Welfare Regime |

S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S6, S7, S9, S10 |

S1, S2, S3, S5, S6, S7, S9, S10 |

S1, S2, S3, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S2, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S1, S2, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S2, S3, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

S2, S3, S4, S5, S6, S7, S9, S10 |

S2, S6, S9, S10 |

S3, S5, S6, S9, S10 |

58 |

|

Conservative Welfare Regime |

- |

S3, S4, S5 |

- |

S1, S3 |

S3 |

S4, S9 |

S3, S4 |

S3, S4, S5 |

- |

13 |

|

Total |

15 |

17 |

13 |

13 |

13 |

14 |

17 |

14 |

11 |

127 |

* The responses provided by participants revealed multiple themes.

Discussion

Esping-Andersen’s welfare state typology, introduced in 1990, classifies 18 countries into three categories based on their socio-economic, political, and socio-cultural structures. However, as the number of countries has grown, and as social structures have evolved, the relevance and inclusiveness of this classification have been increasingly questioned. According to the United Nations data from 2022, there are now 208 countries worldwide, yet, Esping-Andersen’s typology has not been systematically updated, which is leading to criticism. These critiques extend beyond the increase in the number of countries to include shifts in family structures, gender roles, and social policy practices. For example, changes in intra-family roles – such as women becoming primary household heads, or the emphasis on family-based rather than individual social assistance – underscore the limitations of the existing framework. Additionally, the reliance on social insurance schemes as a key criterion for defining welfare typologies tends to overlook the diversity of social policy reforms and practices. This approach oversimplifies the complex and dynamic nature of welfare systems, making it increasingly difficult to fit countries into a single, rigid classification. As a result, many nations exhibit characteristics of multiple welfare typologies simultaneously, necessitating a reassessment of the flexibility and validity of the current classification models.

A review of the literature on welfare typologies in Türkiye highlights the influential works of Buğra and Keyder (2013) and Gülden and Özalp (2017). In New Poverty and Turkey’s Changing Welfare Regime, Buğra and Keyder examine the impact of poverty on welfare typologies through interviews with Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) in Istanbul. Their study underscores the inadequacy of CSO-provided assistance and emphasizes the need for a more active role of the State’s social assistance mechanisms. They advocate for cash-based rather than in-kind social aid, particularly targeting women, and stress the importance of enhancing support for children’s education.

Gülden and Özalp (2017), in Classification Studies of Welfare Regimes: The Gender Dimension, explore the intersection of gender and welfare state classifications. Their research analyzes how different welfare typologies shape gender roles and assesses Türkiye’s position within this framework. By drawing from both national and international literature, they construct a welfare map of Türkiye, based on which, they identify unemployment and poverty as the central indicators of social and welfare policies. Additionally, their study employs a novel approach by incorporating interviews with humanitarian aid organizations operating in Türkiye. This perspective provides deeper insights into the welfare models shaping Türkiye’s social policy landscape and offers alternative viewpoints on the classification of its welfare regime.

This study represents a significant contribution to both the academic literature on the welfare regime typologies and the practical field of social policy. By developing a comprehensive regional welfare map of Türkiye, this research sheds light on the intricate ways in which welfare policies are shaped by local conditions, revealing a complex interplay between national frameworks and regional specificities. The findings demonstrate that Türkiye does not conform neatly to any single welfare typology but rather exhibits a hybrid model that incorporates elements of the liberal, conservative, and social democratic welfare systems. This mixed typology reflects the diverse socio-economic and political landscapes within the country, where different regions experience varying degrees of State intervention, market influence, and reliance on family structures for welfare provision.

One of the key findings of this study is the pivotal role played by Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) in shaping welfare outcomes at the regional level. In many parts of Türkiye, NGOs fill critical gaps in the State’s welfare provision, particularly in those regions where the State’s presence is limited, or where market-driven welfare solutions are inadequate. These organizations are instrumental in addressing the needs of disadvantaged groups, such as the unemployed, older adults, and low-income families, through a combination of direct assistance and advocacy. The active participation of NGOs highlights the importance of non-governmental actors in the Turkish welfare system and underscores the need for policies which would foster collaboration between the State, the market, and civil society.

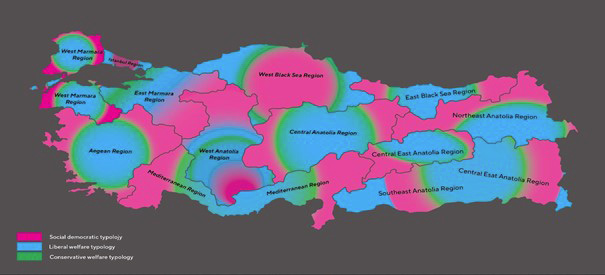

The regional welfare map developed through this research provides a detailed picture of how welfare policies are being implemented and experienced across Türkiye. In regions like Western Anatolia and the Aegean, social democratic welfare models are more prevalent, characterized by a high degree of State intervention in social welfare. In contrast, regions like Eastern Anatolia and Southeastern Anatolia exhibit a stronger reliance on conservative welfare models, where family and community networks play a more significant role in supporting individuals. The liberal welfare model, marked by a greater reliance on market forces, is more evident in economically developed regions such as Istanbul and the Marmara region, where State welfare is often seen as a supplement to market-driven solutions. The findings indicate that NGOs serve a crucial complementary function in delivering welfare services, particularly in regions where the State support is insufficient. This variation in regional welfare policies across Türkiye underscores the importance of developing social policy solutions that are responsive to local needs. In other words, NGOs in Türkiye are playing a vital role in supporting and enhancing the implementation of welfare policies, by filling gaps where public provisions fall short.

Figure 1.

Welfare typology map of Türkiye

Source: Authors’ own research. (Prepared by İnal Demiral)

This study’s findings have important implications for policymakers. By recognizing the regional disparities in welfare provision, policymakers can develop more targeted and effective social policies which would address the specific needs of different regions. For instance, regions with higher levels of poverty and unemployment may require more robust state intervention and greater support for NGOs, while more affluent regions may benefit from policies that encourage market-based solutions and promote private sector involvement in welfare provision. The regional welfare map also provides a valuable tool for assessing the impact of existing policies and identifying areas where further intervention is needed.

Moreover, this research contributes to the broader understanding of welfare state development in countries which do not fit neatly into the traditional welfare typologies. Türkiye’s mixed welfare model challenges the notion that welfare systems must conform to a single typology, and instead demonstrates the adaptability of welfare policies in response to local conditions. This has broader relevance for other countries with diverse socio-political contexts, where regional disparities necessitate a more flexible approach to the welfare policy.

Conclusion

Türkiye’s diverse socio-economic, political, cultural, and geographical characteristics, spanning the East-West and North-South axes, have shaped its cosmopolitan structure since the inception of the Republic. Over time, the country has undergone significant transformations in its welfare regime due to various economic and political policies. This evolution, influenced by both domestic dynamics and global trends, defies simple classification within a single welfare model. While not fully embracing either a market-driven liberal approach or a universal social democratic regime seen in developed nations, Türkiye’s welfare policies have evolved notably.

The collaboration between the State, primarily through Social Assistance and Solidarity Foundations (SYDD), and Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) highlights this transformation. NGOs, operating under means-tested criteria, play a pivotal role in delivering social services to vulnerable groups such as the elderly, disabled individuals, women, and children. Initially classified under Esping-Andersen’s Conservative (Corporatist) welfare model, Türkiye’s welfare landscape has shifted over time, increasingly resembling aspects of the Southern European model. However, it defies strict categorization due to its hybrid nature incorporating elements from multiple welfare regimes.

Regional analyses underscore this complexity, revealing Türkiye’s welfare system as a hybrid which integrates conservative, liberal, and social democratic elements. NGOs are instrumental in addressing unemployment and poverty, acting as intermediaries in the labor market and ensuring effective distribution of charitable aid. Despite some regional variations where traditional social structures prevail, national programs targeting children are widespread. This dynamic and multidimensional welfare structure calls for region-specific interventions so that to address socio-economic disparities effectively.

In conclusion, this study has synthesized data from across Türkiye’s 81 provinces to provide a comprehensive overview of the nation’s welfare landscape. The findings reveal that Türkiye exhibits a hybrid welfare system, characterized by a blend of liberal, conservative, and social democratic elements. Regional disparities are significant, with some areas relying more heavily on the State’s intervention, while others depend on family support or market-based solutions. NGOs play a crucial role in bridging gaps in welfare provision, particularly in regions where the State’s support is limited. By integrating these diverse regional patterns, this research offers a holistic understanding of welfare in Türkiye, highlighting the need for targeted policies that address the specific needs of each region while leveraging the strengths of the various welfare models in place.

This research emphasizes the pivotal role of NGOs, the influence of regional conditions on welfare models, and the necessity of comprehensive approaches to enhance the social cohesion and equity nationwide. Future research should continue by exploring these regional nuances amidst the ongoing economic, political, and social transformations, aiming to inform adaptive welfare strategies that meet evolving societal needs and challenges.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely appreciate the invaluable contribution of all the NGOs involved in this research.

Declaration of interest statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the submission of this manuscript.

Funding details

This research was supported financially by the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey under the TÜBİTAK 1002B project and produced within the scope of a doctoral thesis.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [N.E.Ö.], upon reasonable request.

Author contributions

N.E.O: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing - original draft, visualization. D.B.S: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing - review & editing. G.C.: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing - review & editing, visualization. A.A.: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing - review & editing.

References

Başkale, H. (2016). Nitel Araştırmalarda Geçerlik, Güvenirlik ve Örneklem Büyüklüğünün Belirlenmesi [Validity, Reliability and Determination of Sample Size in Qualitative Research]. Dokuz Eylül Üniversitesi Hemşirelik Fakültesi Elektronik Dergisi [Dokuz Eylul University Faculty of Nursing Electronic Journal], 9(1), 23-28.

Baran, B., Rojas, A., Britez, D., & Baran, L. (2006). Measurement and analysis of poverty and welfare using fuzzy sets. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Systemics, Cybernetics and Informatics, 99.

Briggs, A. (1961). The welfare state in historical perspective. European Journal of Sociology/Archives Europeennes de Sociologie, 2(2), 221-258.

Buğra, A., & Keyder, Ç. (2003). Yeni yoksulluk ve Türkiye’nin değişen refah rejimi [New poverty and Turkey’s changing welfare regime]. Ankara: UNDP.

Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Princeton University Press.

Esping-Andersen, G. (1991). The three political economies of the welfare state. Sociologický Časopis/Czech Sociological Review, 545-567.

Flora, P. (1986). Growth to limits: The Western European welfare states since World War II, 4. Walter de Gruyter.

Frericks, P., Gurín, M., & Höppner, J. (2023). Mapping redistribution in terms of family: A European comparison. International Sociology, 38(3), 269-289. https://doi.org/10.1177/02685809231168135

Goetz, J. P., & LeCompte, M. D. (1984). Ethnography and qualitative design in educational research. Academic Press.

Gough, I. (2001). Globalization and regional welfare regimes: The East Asian case. Global Social Policy, 1(2), 163-189.

İslamoğlu, A. H., & Alnıaçık, Ü. (2014). Sosyal bilimlerde araştırma yöntemleri [Research methods in social sciences]. Beta Yayınevi.

Kaariainen, J., & Lehtonen, H. (2006). The variety of social capital in welfare state regimes: A comparative study of 21 countries. European Societies, 8(1), 27-57.

Kirk, J., & Miller, M. L. (1986). Rehability and validity in qualitative research. Sage.

Koray, M. (2005). Sosyal Politika [Social Policy]. İmge Kitabevi, İmge Kitabevi Yayınları, 2. Baskı, Ankara.

Küçükoba, E. (2022). Refah devleti bağlamında sosyal politika, sosyal hizmetin tarihi gelişimi ve Türkiye [Social policy in the context of the welfare state, the historical development of social work and Turkey]. Toplumsal Politika Dergisi [Journal of Social Policy], 3(2), 164-176.

Lewis, O. (1966). The culture of poverty. Scientific American, 215(4), 19-25.

Merriam, S. B. (2013). Nitel araştırma: Desen ve uygulama için bir rehber [Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation] (Translated by S. Turan). Nobel Yayıncılık.

Mishra, R. (1997). Globalization and the welfare state. Edward Elgar.

Padda, I. U. H., & Hameed, A. (2018). Estimating multidimensional poverty levels in rural Pakistan: A contribution to sustainable development policies. Journal of Cleaner Production, 197, 435-442.

Roosma, F., & van Oorschot, W. (2020). Public opinion on basic income: Mapping European support for a radical alternative for welfare provision. Journal of European Social Policy, 30(2), 190-205. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928719882827

Rowntree, B. S. (1901). Poverty: A study in town life. Macmillan.

Şenkal, A. (2024). Küreselleşme Sürecinde Sosyal Politika [Social Policy in the Process of Globalization]. Umuttepe Yayınları.

Tokol, A., & Alper, Y. (2015). Sosyal politika [Social Policy] (6th ed.). Dora Yayınevi, Bursa.

TÜİK. (2012). İstatistik göstergeler 1923-2011[Statistical indicators 1923-2011]. TÜİK. http://www.tuik.gov.tr

Ülgen, G., & Özalp, L. F. A. (2017). Refah rejimleri sınıflandırma çalışmaları: cinsiyet boyutları [Classification of welfare regimes: gender dimensions]. Marmara Üniversitesi İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Dergisi [Marmara University Journal of Economics and Administrative Sciences], 39(2), 639-658.

Whittemore, R., Chase, S. K., & Mandle, C. L. (2001). Validity in qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research, 11(4), 522-537.

Yay, S. (2020). Tarihsel süreçte Türkiye’de sosyal devlet [Social state in Turkey in the historical process]. 21. Yüzyılda Eğitim ve Toplum Eğitim Bilimleri ve Sosyal Araştırmalar Dergisi [Journal of 21st Century Education and Social Educational Sciences and Social Research], 3(9), 147-162.

Yıldırım, A., & Şimşek, H. (2011). Sosyal bilimlerde nitel araştırma yöntemleri [Qualitative research methods in social sciences]. Seçkin Yayıncılık.

Zimmermann, K., & Graziano, P. (2020). Mapping different worlds of eco-welfare states. Sustainability, 12(5), 1819. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12051819