Social Welfare: Interdisciplinary Approach eISSN 2424-3876

2025, vol. 15, pp. 142–159 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/SW.2025.15.8

Breast Cancer Support Groups and Benefits Associated with Their Participation: A Narrative Literature Review

Merle Varik

Tartu Applied Health Sciences University

Nooruse 5, Tartu 50405, Estonia

E-mail: merlevarik@nooruse.ee

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8173-1056

https://ror.org/04twzkg92

Heli Mäesepp

Tartu Applied Health Sciences University

Nooruse 5, Tartu 50405, Estonia

E-mail: heli.maesepp@emu.ee

https://ror.org/04twzkg92

Maikela Dolgin

Tartu Applied Health Sciences University

Nooruse 5, Tartu 50405, Estonia

E-mail: maikellad@gmail.com

https://ror.org/04twzkg92

Abstract. Support groups are widely established in the world and serve as effective psychoeducational interventions, reducing stress, anxiety, and depression while enhancing the overall well-being and self-efficacy. The study aimed to describe the characteristics of support groups tailored for women diagnosed with breast cancer and the benefits associated with their participation. The narrative literature review strategy was applied. A search was performed in PubMed, Science Direct, and EBSCO from 2013 to 2023, and SANRA was used to evaluate the quality of the articles. The narrative analysis incorporated 29 research articles. The study findings reveal that support groups are held at various stages of the cancer journey, and participation in support groups significantly benefits women diagnosed with breast cancer by providing social support, information, and knowledge. Peer support and forming social bonds contribute to well-being, while communication opportunities address social needs. Overall, support groups are an opportunity to empower women, and participation in them is a valuable chance for individuals to connect, share experiences, increase knowledge of the disease, and receive the necessary emotional reinforcement.

Keywords: breast cancer, women, support groups, well-being.

Recieved: 2025-03-06. Accepted: 2025-06-27

Copyright © 2025 Merle Varik, Heli Mäesepp, Maikela Dolgin. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access journal distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

The incidence of breast cancer has increased in recent decades. In 2020, 2.3 million new cases of breast cancer were diagnosed worldwide, whereas, in the past five years, 7.8 million women have been diagnosed with the disease (Breast Cancer, 2023). Since the 1990s, breast cancer mortality rates have started to decline, which can be attributed to the implementation of screening programmes enabling early disease detection and more effective treatment modalities. Breast cancer patients experience emotional and psychological challenges during treatment and after recovery from the disease. These challenges include fatigue, discomfort, changes in the body image, the impact of the disease on work and personal life, financial difficulties, and uncertainty about the future (McCaughan et al., 2017; Stephen et al., 2017; Kadravello et al., 2021). High levels of stress, anxiety, depression, decreased psychosocial well-being, and reduced self-efficacy have been observed among women diagnosed with breast cancer (McCaughan et al., 2017; Ghanbari et al., 2021; Alshamsi et al., 2023; Ursavaş & Karayurt, 2017).

The significance of furnishing psychosocial support for women diagnosed with breast cancer to augment their well-being, both during and after treatment, cannot be overstated, and various psychoeducational interventions have been implemented: information materials are shared, and counselling and training sessions are provided. Additionally, breast cancer support groups (SG) have become a common psychoeducational intervention suitable for women with the disease, allowing them to share personal experiences and learn from those of other patients (McCaughan et al., 2017; Alshamsi et al., 2023; Lin et al., 2022; Wells et al., 2014).

Since members of breast cancer support groups have personal experience with the illness, they can share information based on this experience with other group members regarding cancer treatment, its side effects, coping with daily life, and other topics (Beck & Keyton, 2014). Compared to counselling provided by healthcare professionals, the atmosphere in SGs is more relaxed and informal, allowing many women to express themselves more freely (Lognos et al., 2022). Despite the benefits of SG in reducing stress, anxiety, and depression while enhancing well-being and self-efficacy, breast cancer support groups remain relatively uncommon in the Baltic countries. This gap underscores the idea to develop and integrate these interventions to provide essential psychological and emotional support for women diagnosed with breast cancer. To address this need, the present article aimed to describe the characteristics of support groups for women diagnosed with breast cancer and the benefits associated with their participation.

Methodology

This study uses a narrative literature review within the biopsychosocial framework to explore how biological, psychological, and social factors shape the experiences of women with breast cancer. The biopsychosocial approach (Borrell-Carrió et al., 2004) provides a comprehensive understanding of how support groups impact well-being, while highlighting the roles of physical health, emotional coping, and social support, as well as psychological resilience and social connectedness in health outcomes. The narrative literature review is a flexible, rigorous, and practical method, grounded in the interpretivist paradigm (Sukhera, 2022), that allows for critical examination and synthesis of existing knowledge. Unlike systematic reviews, which follow rigid protocols, narrative reviews uncover patterns, conceptual connections, and context-specific meanings across studies (Greenhalgh et al., 2018). This approach is particularly useful in interdisciplinary fields and broad research questions, identifying trends, gaps, and suggesting future research avenues (Ferrari, 2015).

Search strategy

Articles published between 2013 and 2023 in English were sourced from electronic databases such as PubMed, Science Direct, and EBSCO, by using search terms like ‘women’, ‘breast cancer’, ‘benefits’, and ‘support groups’. Search strategies were adapted to every database with the use of mesh terms.

The screening process, which was carried out independently by two authors, ensured relevance based on the following inclusion criteria: (1) nature of SG for women, (2) benefits of participation, and (3) study design, including qualitative and quantitative methods or literature reviews. The quality was assessed by using the Scale for the Assessment of Narrative Review Articles, as outlined in (Baethge et al., 2019), and decisions on article inclusion were made collaboratively by all authors.

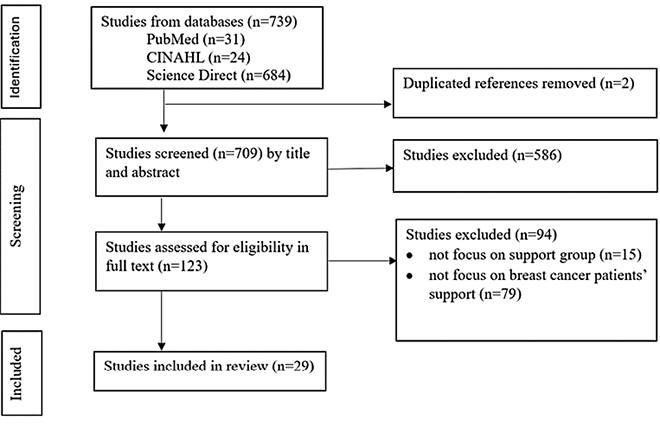

We identified a total of 739 publications. After deduplication, titles and abstracts were screened, and 123 articles were selected for full-text review. Finally, we included 29 publications: 24 empirical studies and 5 literature reviews (Figure 1).

Data analysis

In the initial stages, the key themes were identified inductively, coded, and grouped into categories, facilitating the detection of recurring patterns and relationships across the studies (Baethge et al., 2019). The biopsychosocial framework guided the synthesis of the literature and supported the identification of both patterns and gaps in understanding the benefits of SG. The analysis was conducted by two researchers working collaboratively to identify and categorize key themes, followed by an independent analysis by a third researcher. The results were then compared to assess the consistency and overlap between the assigned codes. Any discrepancies were discussed and resolved through further deliberation, thereby ensuring a unified and coherent approach to data interpretation. This process contributed to the overall reliability and consistency of the findings. Together, we identified six categories: (1) structure, duration, and facilitator; (2) activities, topics, and methods; (3) psychosocial support; (4) increased knowledge and awareness; (5) health behaviour; and (6) self-perception and resilience. These categories were subsequently grouped into two themes: (1) characteristics of SG, and (2) the benefits associated with breast cancer patient participation in SG.

Details of the included studies are summarised in Appendix 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the database search and study selection

Results

Characteristics of support groups for women diagnosed with breast cancer

Structure, Duration, and Facilitators

Support groups for women diagnosed with breast cancer can be either structured or unstructured and take place either face-to-face or online. In structured SGs, the format and content of meetings are regulated. The range of topics discussed in the SG may be predefined or adapted to the participants’ needs, with each meeting focusing on a specific theme (Irawati et al., 2019) or shaped by the composition and characteristics of the group (Pongthavornkamol et al., 2014). The number of members in the SG ranged from 8 to 20 individuals in one face-to-face group (Beck & Keyton, 2014; Pongthavornkamol et al., 2014; Abu Kassim et al., 2013). It has been observed that participants experience more significant benefits when group membership is homogeneous. When there is too much diversity within the group, it can hinder meaningful connections, as members may struggle to relate to each other’s issues (Clougher et al., 2023).

In addition to face-to-face meetings, online SG are becoming more common (McCaughan et al., 2017; Stephen et al., 2017; Kadravello et al., 2021; Lepore et al., 2014; Bender et al., 2013; Sillence, 2012; Chee et al., 27; Batenburg & Das, 2014; Moon et al., 2017; Harmon et al., 2021), either combined or integrated with various technology solutions (Ghanbari et al., 2021; Jung et al., 2023; Swartz et al., 2022). These groups often incorporate various technological tools such as social networks (Kadravello et al., 2021; Sillence, 2013), mobile applications (Ghanbari et al., 2021; Jung et al., 2023), and even video games to increase engagement and support (Swartz et al., 2022). Adoption of innovative solutions in support group settings enhances choices, thereby allowing the participation of people previously hindered by time constraints or other limitations. Modern technological solutions facilitate the aggregation of more members with similar diagnoses, thus allowing more credible peer support and ensuring better availability of information (Bender et al., 2013). Overcoming spatial constraints also enables more specialised online SG to be organised, such as those tailored for minority populations (Chee et al., 2017). Despite these advantages, online SG participants may be less active in group discussions and may only engage by reading posts, although even passive participation is still considered valuable (Bender et al., 2013; Hu et al., 2019). Moon et al. (2017) highlighted the importance of breast cancer survivors in online groups, as they provide valuable emotional support and share information on topics such as symptoms and treatment.

The duration of SG varies from 1 to 8 weeks (Alshamsi et al., 2023; Pongthavornkamol et al., 2014; Björneklett et al., 2013). However, longer participation has been shown to produce better results. For example, Beck and Keyton (2014) described a long-term SG that was operating for seven years, primarily with breast cancer survivors. Meeting duration typically falls within the range of 50–90 minutes (Irawati et al., 2019; Beck & Keyton, 2014; Pongthavornkamol et al., 2014); however, some of them were longer, with some lasting up to 3 hours 40 minutes (Leşe et al., 2014).

SGs are usually facilitated by healthcare professionals or social workers, or solely by patients with extensive experience (McCaughan et al., 2017; Stephen et al., 2017), or a mixture of both (Beck & Keyton, 2014). Several researchers emphasized that healthcare professionals should facilitate the meetings (Stephen et al., 2017; Clougher et al., 2023; Hu et al., 2019) because, without the guiding role of a professional, there is a risk that misinformation about breast cancer may spread within the group. The central role of a facilitator is to provide information to group members, primarily in the form of facts rather than opinions and recommendations. Additionally, the facilitator is involved in questioning group members and expressing emotions (Beck & Keyton, 2014). The role of the facilitator can involve directing the conversation towards specific topics, leading the discussion, and intervening in the conversation in order to maintain a safe environment if group members behave hostilely towards each other (Stephen et al., 2017). Therefore, autocratic individuals are not suitable as facilitators but rather as those who can empower group members and motivate them to ask questions and share their stories (Ursavaş & Karayurt, 2017).

Activities, topics, and methods

The activities offered in SG vary widely depending on the group’s structure and focus. Sometimes, participation is part of a broader patient support program that includes lectures, training, and cognitive behavioural therapy (Alshamsi et al., 2023). Other groups may focus primarily on educational content, such as treatment options, coping strategies, and lifestyle adjustments (Lepore et al., 2014; Ono et al., 2016). Often, a combination of activities is tailored to meet the group’s specific needs (Pongthavornkamol et al., 2014; Clougher et al., 2023; Lepore et al., 2014; Ono et al., 2016). Educational and therapeutic elements are frequently integrated with physical activities (e.g., yoga, exercise), spiritual practices (e.g., mindfulness, meditation), and reflective tools (e.g., journaling) to support emotional processing and self-awareness (Shannonhouse et al., 2014). Interactive methods, such as role-play, skill-building, and group problem-solving, are also employed to enhance emotional resilience and coping abilities (Pongthavornkamol et al., 2014). Topics often extend beyond illness management to include the body image, intimacy, depression, anxiety, and ethical issues (Lepore et al., 2014; Ono et al., 2016). For example, Lepore et al. (2014) conducted a six-session program covering self-esteem, physical activity, and mental health, while Ono et al. (2016) included communication, ethical issues and role-playing scenarios. Additionally, technology-enhanced interventions have emerged, such as a video game and a mobile app-based SG designed to promote physical activity, where the participants could engage individually and share results with the group (Swartz et al., 2022).

Benefits associated with breast cancer patient participation in support groups

Psychosocial Support

Women diagnosed with breast cancer often face uncertainty regarding the disease, treatment options, and outcomes – not only at the time of diagnosis, but throughout and beyond the course of treatment.

Coping with treatment-related physical and emotional side effects can be challenging, while creating a significant need for both emotional and social support (Stephen et al., 2017; Lin et al., 2022; Lognos et al., 2022). This need is a common motivation for joining breast cancer support groups, where participation is often driven by the desire to meet unmet psychosocial needs, even when initially motivated by a more casual interest (Leşe et al., 2014). SGs help address these needs by fostering emotional support through shared experiences, and enabling participants to connect with others facing similar challenges (Bender et al., 2013). These groups provide a safe environment where women can express their concerns and receive non-judgemental feedback, offering emotional relief, particularly for those lacking supportive conversation partners in their personal lives (Clougher et al., 2023).

A key benefit of participation is the receipt of personalised emotional support from fellow members, which not only helps women cope more effectively with the psychological impact of breast cancer but also fosters a sense of empowerment (Lognos et al., 2022; Ono et al., 2016). Numerous studies provide empirical evidence for the psychosocial benefits of SG, including reductions in anxiety (Ghanbari et al., 2021; Alshamsi et al., 2023; Pongthavornkamol et al., 2014), stress (Jung et al., 2023), and depression (McCaughan et al., 2017; Alshamsi et al., 2023; Lepore et al., 2014; Björneklett et al., 2013; Batenburg & Das, 2014). Furthermore, Alshamsi et al. (2023) reported that women who participated in support groups after recovering from breast cancer demonstrated significantly higher quality of life scores compared to non-participants.

Increased knowledge and awareness

Breast cancer SGs for women help satisfy the educational or informational needs of group members, as participation in the group enables women diagnosed with breast cancer to obtain important information (Alshamsi et al., 2023; Beck & Keyton, 2014; McCaughan et al., 2017; Leşe et al., 2014; Bender et al., 2013; Harmon et al., 2021). The primary reasons for joining SG were obtaining information about the disease, seeking advice from women with breast cancer experience, and becoming better informed so that to make treatment-related decisions (Harmon et al., 2021). Access to accurate information is especially valuable, as women with breast cancer often face high levels of uncertainty. Meeting their informational needs helps to clarify what lies ahead, thus reducing anxiety and fostering a sense of control (Bender et al., 2013). SG may offer guidance on various topics, including treatment options, managing daily life, physical activity, nutrition, healthy lifestyle choices, patient rights, and interpreting health information (Lognos et al., 2022; Alshamsi et al., 2023; Leşe et al., 2014). Additionally, SGs contribute to psychological adjustment by offering a space for women to learn how to manage treatment-related side effects and emotional challenges (Harmon et al., 2021). Supplementing SG meetings with topics that improve psychological coping skills, such as stress management, problem-solving, and training, may also contribute to meeting psychological needs.

Health Behaviour

SG not only provides emotional reassurance but also plays a crucial role in enhancing health behaviour. The acquisition of information and heightened awareness have been shown to foster positive changes in health behaviours, contributing to more informed and proactive management of one’s health. The study by Pongthavornkamol et al. (2014) highlighted that participation favours women’s health behaviour. By assessing various aspects of health behaviour, including interpersonal relationships, nutrition, responsibility for health, physical activity, stress management, and spirituality, the study found improvements in the participants’ health behaviours both in the short term (5–7 weeks post-participation) and long-term perspective (six months later). A randomised controlled trial conducted by Jung et al. (2023), focusing on a mobile application-based breast cancer SG (n=185), showed that the participants had higher levels of physical activity. The study concluded that mobile application-based groups effectively increase physical activity in breast cancer patients. The study by Swartz et al. (2022) demonstrated that participation in a video game-based breast cancer SG increased the physical activity of the group members. The research findings showed that the video game promoted physical activity and significantly increased physical activity. Furthermore, the results of this study showed that participation in the video game-based SG increased the physical capacity of women with breast cancer and improved their walking speed.

Self-perception and resilience

Participation in a SG helps women gain a different perspective on their illness and move forward with their lives despite the disease and its side effects. Being a member of a group provides examples from other women diagnosed with breast cancer and the chance to meet others who have successfully recovered from the disease and/or managed their lives despite it. These interactions can foster an increased self-confidence in coping with the challenges posed by the disease (Ono et al., 2016). Additionally, participation in support groups has been linked to an increased self-esteem, alongside reduced anxiety (Ghanbari et al., 2021). In the study by Shannonhouse et al. (2014) involving 14 breast cancer survivors, it was found that participation in SG led to a change in priorities for some women. Consequently, the experience of breast cancer was reframed and increasingly viewed as a form of personal rebirth, despite the negative aspects associated with the disease. It was noted that, in terms of its prevalence, breast cancer was perceived as a new form of normalcy. Similarly, a randomised controlled trial conducted by Björneklett et al. (2013) involving 382 participants showed that women in SG experienced improved cognitive functioning, body image perception, and future perspective compared to those in the control group. However, in a quasi-experimental study among 76 women diagnosed with breast cancer, the indicator of self-efficacy was, on average, 1.4 times higher among participants than non-participants, and the sample for this study included only women undergoing chemotherapy. One possible explanation for this result is that many women who did not participate in SG may have received similar social support from family members and close relatives. (Irawati et al., 2019).

Discussion

The benefits of participating in support groups have been acknowledged in previous studies, particularly in relation to mental health, with positive outcomes attributed to an enhanced resilience as well as emotional and social support. However, the extent of these benefits depends on structural and contextual factors, including the group format, facilitation, duration, and activities. Homogeneous groups tend to foster stronger connections and better outcomes, whereas diversity may hinder mutual understanding.

SG may be structured or unstructured, and conducted either face-to-face or online. While structured groups offer thematic consistency, unstructured formats may allow greater flexibility. Homogeneous composition often enhances peer bonding and the relevance of discussions, while excessive diversity may inhibit connection (Clougher et al., 2023). Online formats, enhanced by digital tools like social media, mobile apps, and gamified platforms, expand access but may discourage from more active participation (Bender et al., 2013; Jung et al., 2023; Swartz et al., 2022). The group duration ranges from 1 to 8 weeks, with longer involvement linked to greater benefit. Meetings typically last 50–90 minutes. Facilitators, whether healthcare professionals, or peers, play a pivotal role in ensuring the success of a SG. Professional facilitators can help mitigate misinformation (Stephen et al., 2017), while peer-led or co-facilitated groups may foster a stronger emotional connection and trust (Beck & Keyton, 2014; McCaughan et al., 2017). The diversity of activities ranged from psychoeducational workshops to physical exercises. These findings highlight the importance of a tailored approach, whereby the group’s focus adjusts to its participants’ changing needs to increase SG effectiveness. Further research should explore how SG characteristics can be adapted to better reflect the participants’ needs across various stages of illness, and how facilitation practices and content design can support consistent engagement and a psychologically safe environment.

Emotional support and shared experience lie at the heart of SG, fostering empathy, reducing isolation, and enabling expression without judgment. These groups promote self-esteem, empowerment, and psychological resilience (Shannonhouse et al., 2014, Beck & Keyton, 2014), aligning with the biopsychosocial model, where emotional and cognitive resources are interdependent. As emotional safety increases, participants become more receptive to informational support, thus reinforcing this bidirectional dynamic (Clougher et al., 2023).

While many studies confirm that SG participation alleviates anxiety, depression, and stress (Ghanbari et al., 2021; Alshamsi et al., 2023), some report no significant effects (Björneklett et al., 2013; McCaughan et al., 2017). Women in SG often report reduced physical and mental fatigue (Björneklett et al., 2013; Chee et al., 2017). However, the impact of SG on physical health outcomes remains underexplored. As SGs primarily address emotional and social needs, their direct influence on physical health may be limited. Nevertheless, improvements in mental health may indirectly enhance physical well-being by lowering stress, promoting healthier self-care, and encouraging positive lifestyle changes (Pongthavornkamol et al., 2014; Jung et al., 2023; Swartz et al., 2022). Additionally, some studies highlight a positive influence of SG on health behaviours, with their participants reporting increased physical activity and healthier lifestyle choices. Technological integration via apps or gamification can further enhance these effects by embedding support and self-monitoring into daily routines. These platforms allow users to track metrics such as activity levels, while also offering emotional and social support to reduce isolation.

Support groups are fundamentally built on interpersonal social support, involving information exchange, mutual advice, constructive feedback, and addressing both emotional and informational needs (Beck & Keyton, 2014). Beyond individual benefits, such support structures contribute to broader social processes by fostering a culture of shared knowledge and collective empowerment. They also play a key role in promoting positive body image and self-acceptance (Lepore et al., 2024; Björneklett et al., 2013). As Clougher et al. (2023) note, meeting emotional needs increases receptiveness to information, thus reinforcing the reciprocal nature of emotional and informational support.

Our findings align with the biopsychosocial framework which views health as the result of dynamic interactions between biological, psychological, and social factors. Support groups exemplify this model by simultaneously addressing emotional needs, encouraging adaptive coping strategies, and fostering social connectedness, all of which contribute to the overall well-being. Improvements in mental health may indirectly support physical health, thus illustrating the reciprocal nature of these domains within the biopsychosocial paradigm. Through collective support and shared experience, SGs help normalize the emotional challenges of breast cancer, while fostering resilience and empowerment. Participation provides meaningful social interaction, addressing social needs and reducing isolation. Future research should examine barriers to implementation in the Baltic region and explore culturally adapted models that ensure accessibility and sustainability. Moreover, positioning SG within broader social science frameworks may help illuminate their role in fostering social cohesion, empowerment, and resilience among women with breast cancer.

Conclusion

Breast cancer support groups serve as vital social structures that offer both emotional and informational support, facilitating coping and adaptation for women diagnosed with breast cancer. These groups play a crucial role in addressing emotional and social needs by fostering connections, encouraging the exchange of experiences, and providing psychological reinforcement. Participation in SG is associated with numerous benefits, including improved mental health outcomes such as reduced stress, anxiety, and depression, along with an enhanced quality of life and the overall well-being. Additionally, SG can positively affect physical health by promoting healthier lifestyles and an increased physical activity.

Strengthening collaboration between healthcare professionals and support networks is essential to ensure the effective integration of SG into healthcare systems, so that women could be provided with comprehensive support throughout the treatment and recovery journey.

Author contributions

Merle Varik: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, visualization.

Heli Mäesepp: methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing – review and editing

Maikela Dolgina: methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing – review and editing

References

Abu Kassim, N. L., Hanafiah, K. M., Samad-Cheung, H., & Rahman, M. T. (2013). Influence of support group intervention on quality of life of Malaysian breast cancer survivors. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health, 27(2), NP495–NP505. https://doi.org/10.1177/1010539512471074

Alshamsi, H. A., Asee, H. A., Obeid, D. A., & Aljohi, A. (2023). The efficacy of psychoeducational support group for Saudi breast cancer survivors. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, 24(2), 569–574. http://doi.org/10.31557/APJCP.2023.24.2.569

Baethge, C., Goldbeck-Wood, S. & Mertens, S. (2019). SANRA—a scale for the quality assessment of narrative review articles. Research Integrity and Peer Review, 4(1), Article 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41073-019-0064-8

Batenburg, A., & Das, E. (2014). Emotional approach coping and the effects of online peer-led support group participation among patients with breast cancer: a longitudinal study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 16(11), Article e256. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3517

Beck, S. J., & Keyton, J. (2014). Facilitating social support: member–leader communication in a breast cancer support group. Cancer Nursing, 37(1), E36–E43. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0b013e3182813829

Bender, J. L., Katz, J., Ferris, L. E., & Jadad, A. R. (2013). What is the role of online support from the facilitators’ perspective of face-to-face support groups? A multi-method study of the use of breast cancer online communities. Patient Education and Counseling, 93(3), 472–479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2013.07.009

Björneklett, H. G., Rosenblad, A., Lindemalm, C., Ojutkangas, M. L., Letocha, H., Strang, P., & Bergkvist, L. (2013). Long-term follow-up of a randomised study of support group intervention in women with primary breast cancer. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 74(4), 346–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2012.11.005

Borrell-Carrió, F., Suchman, A. L., & Epstein, R. M. (2004). The biopsychosocial model 25 years later: principles, practice, and scientific inquiry. Annals of family medicine, 2(6), 576–582. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.245

Breast Cancer. (2023). World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/breast-cancer. Accessed 4.09.2023

Ferrari, R. (2015). Writing narrative style literature reviews. Medical Writing, 24(4), 230–235. https://doi.org/10.1179/2047480615Z.000000000329

Chee, W., Lee, Y., Im, E. O., Chee, E., Tsai, H. M., Nishigaki, M., & Mao, J. J. (2017). A culturally tailored Internet cancer support group for Asian American breast cancer survivors: a randomised controlled pilot intervention study. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 23(6), 618–626. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633X16658369

Chou, F. Y., Lee-Lin, F., & Kuang, L. Y. (2016). The effectiveness of support groups in Asian breast cancer patients: an integrative review. Asia-Pacific Journal of Oncology Nursing, 3(2), 157–169. https://doi.org/10.4103/2347-5625.162826

Clougher, D., Ciria‐Suarez, L., Medina, J. C., Anastasiadou, D., Racioppi, A., & Ochoa‐Arnedo, C. (2023). What works in peer support for breast cancer survivors: a qualitative systematic review and meta‐ethnography. Applied Psychology: Health and Well‐Being, 16(2), 793-815. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12473

Ghanbari, E., Yektatalab, S., & Mehrabi, M. (2021). Effects of psychoeducational interventions using mobile apps and mobile-based online group discussions on anxiety and self-esteem in women with breast cancer: randomised controlled trial. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 9(5), Article e19262. http://doi.org/10.2196/19262

Greenhalgh, T., Thorne, S., & Malterud, K. (2018). Time to challenge the spurious hierarchy of systematic over narrative reviews?. European journal of clinical investigation, 48(6), Article e12931. https://doi.org/10.1111/eci.12931

Harmon, D. M., Young, C. D., Bear, M. A., Aase, L. A., & Pruthi, S. (2021). Integrating online community support into outpatient breast cancer care: Mayo Clinic Connect online platform. Digital Health, 7, 20552076211048979. https://doi.org/10.1177/20552076211048979

Hu, J., Wang, X., Guo, S., Chen, F., Wu, Y. Y., Ji, F. J., & Fang, X. (2019). Peer support interventions for breast cancer patients: a systematic review. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 174, 325–341. https ://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-018-5033-2

Irawati, H. R., Afiyanti, Y., & Sudaryo, M. K. (2019). Effects of a support group to self-efficacy of breast cancer patients that receiving chemotherapy. JKKI: Jurnal Kedokteran dan Kesehatan Indonesia, 10(3), 246–254. https://doi.org/10.20885/JKKI.Vol10.Iss3.art7

Jung, M., Lee, S. B., Lee, J. W., Park, Y. R., Chung, H., Min, Y. H., & Chung, I. Y. (2023). The impact of a mobile support group on distress and physical activity in breast cancer survivors: randomized, parallel-group, open-label, controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 25, Article e47158. https://doi.org/10.2196/47158

Kadravello, A., Tan, S.-B., Ho, G.-F., Kaur, R., & Yip, C.-H. (2021). Exploring unmet needs from an online metastatic breast cancer support group: A qualitative study. Medicina, 57(7), Article 693. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57070693

Lepore, S. J., Buzaglo, J. S., Lieberman, M. A., Golant, M., Greener, J. R., & Davey, A. (2014). Comparing standard versus prosocial internet support groups for patients with breast cancer: a randomized controlled trial of the helper therapy principle. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 32(36), 4081–4086. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.57.0093

Leşe, M., Leşe, I., & Mili, G. (2014). A support group for breast cancer patients: benefits and risks. Revista de Cercetare si Interventie Sociala, 46, 182–189. https://www.rcis.ro/images/documente/rcis46_13.pdf.

Lin, K. J., Lengacher, C. A., Rodriguez, C. S., Szalacha, L. A., & Wolgemuth, J. (2022). Educational programs for post-treatment breast cancer survivors: a systematic review. European Journal of Gynaecological Oncology, 43(2), 285–314. http://doi.org/ 10.31083/j.ejgo4302036

Lognos, B., Boulze-Launay, I., Élodie, M., Bourrel, G., Amouyal, M., Gocko, X., & Oude Engberink, A. (2022). The central role of peers facilitators in the empowerment of breast cancer patients: a qualitative study. BMC Women’s Health, 22(1), Article 308. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-01892-x

McCaughan, E., Parahoo, K., Hueter, I., Northouse, L., & Bradbury, I. (2017). Online support groups for women with breast cancer. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 3(3), Article CD011652. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011652.pub2

Moon, T. J., Chih, M. Y., Shah, D. V., Yoo, W., & Gustafson, D. H. (2017). Breast cancer survivors’ contribution to psychosocial adjustment of newly diagnosed breast cancer patients in a computer-mediated social support group. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 94(2), 486–514. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699016687724

Ono, M., Tsuyumu, Y., Ota, H., & Okamoto, R. (2016). Subjective evaluation of a peer support program by women with breast cancer: a qualitative study. Japan Journal of Nursing Science, 14(1), 38–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/jjns.12134

Pongthavornkamol, K., Mahakkakanjana, N., & Meraviglia, M. G. (2014). Improving health promoting behaviors and quality of life through breast cancer support Group for Thai women. Pacific Rim International Journal of Nursing Research, 18(2), 125–137. https://he02.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/PRIJNR/article/view/13369.

Shannonhouse, L., Myers, J., Barden, S., Clarke, P., Weimann, R., Forti, A., & Porter, M. (2014). Finding your new normal: outcomes of a wellness-oriented psychoeducational support group for cancer survivors. The Journal for Specialists in Group Work, 39(1), 3–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/01933922.2013.863257

Sillence, E. (2013). Giving and receiving peer advice in an online breast cancer support group. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 16(6), 480–485. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2013.1512

Stephen, J., Rojubally, A., Linden, W., Zhong, L., Mackenzie, G., Mahmoud, S., & Giese-Davis, J. (2017). Online support groups for young women with breast cancer: a proof-of-concept study. Supportive Care in Cancer, 25(7), 2285–2296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3639-2

Sukhera J. (2022). Narrative reviews: flexible, rigorous, and practical. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 14(4), 414–417. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-22-00480.1

Swartz, M. C., Lewis, Z. H., Deer, R. R., Stahl, A. L., Swartz, M. D., Christopherson, U., & Lyons, E. J. (2022). Feasibility and acceptability of an active video game-based physical activity support group (Pink Warrior) for survivors of breast cancer: randomized controlled pilot trial. JMIR Cancer, 8(3), Article e36889. https://doi.org/10.2196/36889

Ursavaş, F. E., & Karayurt, Ö. (2017). Experience with a support group intervention offered to breast cancer women. The Journal of Breast Health, 13(2), 54–61. https://doi.org/10.5152/tjbh.2017.3350

Wells, A. A., Gulbas, L., Sanders-Thompson, V., Shon, E. J., & Kreuter, M. W. (2014). African-American breast cancer survivors participating in a breast cancer support group: translating research into practice. Journal of Cancer Education, 29, 619–625. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-013-0592-8

Appendix

Table 1.

Summary of characteristics of included studies (n=29)

|

First author, |

Country |

Design |

Sample |

Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Abu Kassim et al. 2013 |

Malaysia |

Cross-sectional study |

80 patients: intervention group (n=57) and control group (n=23) |

Emotional well-being positively links to physical, functional, and social well-being. SGs should prioritize emotional support. |

|

Alshamsi et al. 2023 |

Saudi Arabia |

Retrospective cohort study |

54 survivors |

The support programme reduced distress, anxiety, and depression, and improved the quality of life. SGs support resilience and coping, aiding positive stigma. |

|

Batenburg et al. 2014 |

Netherlands |

2-wave longitudinal study |

109 patients |

Online participation improved emotional well-being. Coping style mattered more for less active users; active emotional processing was linked to better psychological outcomes. |

|

Beck et al. 2014 |

USA |

A mixed method |

8 SG meetings |

Members lead SG, rather than professionals. Facilitator training should focus on fostering interaction. Social support arises through dialogue and information sharing. |

|

Bender et al. 2013 |

Canada |

A cross-sectional survey |

73 filled out the questionnaire, and 12 follow-up interviews |

Online communities have bridged gaps in supportive care services by meeting the specific unmet needs of a subset of breast cancer survivors. |

|

Björneklett et al. 2013 |

Sweden |

Randomised controlled study |

261 patients |

SG participation improved cognition, body image, future outlook, and reduced fatigue and anxiety; no significant effect on depression. |

|

Chee et al. 2017 |

USA, South Korea, Taiwan, Japan, UK |

Randomised controlled intervention |

65 survivors, 5 experts |

There were significant positive changes in support care needs and physical and psychological symptoms of the control group. The intervention group showed significantly greater improvements in physical and psychological symptoms and the quality of life. |

|

Chou et al. 2016 |

USA |

An integrative review |

15 studies from 1982 to 2014 |

SGs offer psycho-education (health info, problem-solving, stress management) and effectively reduce distress while supporting the quality of life. |

|

Clougher et al. 2023 |

Spain |

Qualitative systematic review and meta‐ethnography |

Studies from 1997 to 2018, (n=345) |

SGs provide psycho-education (health info, problem-solving, stress management). Peer support builds mutual understanding, emotional connection, and supports a patient-centred journey. |

|

Ghanbari et al. 2021 |

Iran |

Randomised controlld trial |

82 patients: intervention group (n=41) and control group (n=41) |

Mobile apps decrease anxiety and improve self-esteem through psychoeducational interventions. |

|

Harmon et al. 2021 |

USA |

Survey |

102 Mayo Clinic patients using a moderated online patient platform |

Online platform use positively impacted education, empowerment, and peer support; 75% said the community met or exceeded expectations. |

|

Hu et al. |

China |

Qualitative systematic review |

15 randomised controlled trial studies from 2006 to 2018 |

Peer support improves BC patients’ emotions, the quality of life (QoL), and treatment adherence, but web-based peer support without training is ineffective. Peer education is most effective for disease management, emotions, and QoL. |

|

Irawati et al. 2019 |

Indonesia |

Quasi-experimental design |

76 patients: experimental group (n=38) and control group (n=38) |

SG did not significantly improve cancer coping self-efficacy; however, patients receiving support had 1.4 times higher self-efficacy. |

|

Jung et al. 2023 |

South Korea |

Randomised controlled trial |

175 patients: intervention group (n=85) and control group (n=90) |

Intervention group showed positive attitudes towards daily walking. Feedback on step counts and rankings likely boosted self-efficacy. Mobile app-based community reduced mental distress and increased physical activity among BC survivors. |

|

Kadravello et al. 2021 |

Malaysia |

A qualitative study |

22 metastatic BC patients from WhatsApp SG; a total of 13,342 messages |

Women have unmet information, financial, and support needs. Online SG offer global community, fast info exchange, and availability. SG play a key role in providing peer support for patients with psychosocial issues. |

|

Lepore et al. 2014 |

USA |

Randomised controlled trial |

184 BC patients: standard internet SG (n=96) and prosocial internet SG (n=88) |

P-ISG participants showed more supportive behaviours (emotional, informational, companionate), posted more messages focused on others, and expressed less negative emotion. However, they had higher depression and anxiety symptoms post-intervention. S-ISG showed some psychological benefits. |

|

Leşe et al. 2014 |

Romania |

Retrospective study |

26 patients from 23 SG meetings |

Member interactions create a supportive environment where patients feel safer expressing thoughts and problems. They feel stronger in their fight against BC, more useful and confident, and better informed. |

|

Lin et. |

USA |

Systematic literature review |

24 educational programmes/interventions from 2000 to 2020 |

Educational programmes help manage post-treatment symptoms, support patients (including peer support), and improve the quality of life. Patients face persistent physical and psychological symptoms with numerous unmet needs. |

|

Lognos et al. 2022 |

France |

Qualitative study |

11 in-depth interviews with patients |

Patients shared experiences in associations and online forums, promoting engagement, helping individuals become patient-experts, and empowering them. |

|

McCaughan et al. 2017 |

USA |

Systematic literature review |

6 randomised controlled trials (n=492) |

Results show a minimal effect on psychosocial outcomes. Primary outcomes: emotional distress, uncertainty, anxiety, depression; secondary outcome: the quality of life. |

|

Moon et al. |

USA |

Secondary analysis |

236 participants from an online discussion group |

Breast cancer survivors were offered more emotional and informational support than newly diagnosed patients. Emotional support improved the quality of life and reduced depression, while informational support had no significant impact. |

|

Ono et al. 2016 |

Japan |

A qualitative study |

10 interviews with patients |

Peer support-based patient programmes could effectively complement the existing professional support within medical services. |

|

Pongthavornkamol et al. |

Thailand |

Quasi-experimental study |

59 women: experimental group (n=29) and control group (n=30) |

Health-promotion cancer SGs can effectively improve health behaviours and the quality of life in Thai women with breast cancer during and after treatment. Nurses should encourage participation to foster health-promoting behaviours as part of cancer care. |

|

Shannonhouse et al. 2014 |

USA |

A mixed-methods approach |

14 SG meetings |

Interactions with facilitators and SG members are crucial. Pairing experiential activities with wellness psychoeducation increased self-efficacy, enhanced knowledge of nutrition and exercise, and improved self-acceptance, self-awareness, and coping strategies. |

|

Sillence 2013 |

UK |

Qualitative study. |

425 messages posted to a BC support online forum |

Advice exchange in online breast cancer SGs is important. Healthcare professionals should recognize that patients use these forums and provide sufficient guidance to help them choose appropriate advice from peers. |

|

Stephen et al. 2017 |

Canada |

Randomised clinical trials |

96 young survivors: control group (n=47) and experimental group (n=49) |

Synchronous chat was challenging at times, but minimal technical coaching, structure, set topics, and professional facilitation ensured focused, meaningful conversations. A combined moderator indicated that more women benefited from the intervention group, with therapist-led SG being more effective. |

|

Swartz et al. 2022 |

USA |

Randomised controlled pilot trial |

60 survivors |

The intervention was feasible and acceptable. AVG sessions, PA coaching, and survivorship navigation had moderate effects on PA and physical functioning. AVGs with PA counselling can be used in breast cancer SGs to encourage PA and improve the physical function. |

|

Ursavaş et al. 2017 |

Turkey |

SG intervention |

SG meetings (n=20) and participants (n=37) |

SG allow women to discuss, receive education, and share experiences, helping them feel less alone and receive peer support and accurate information. Nurse- and psychologist-led SGs fostered mutual support among the participants. |

|

Wells et al. 2014 |

USA |

Qualitative study |

Secondary analysis of 20 videotaped interviews survivors |

The need for emotional peer support in SGs is greatest during and after treatment. Emotions peaked at diagnosis, followed by a need for ongoing emotional support. |

Note. SG – support group, BC – breast cancer