Social Welfare: Interdisciplinary Approach eISSN 2424-3876

2025, vol. 15, pp. 197–212 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/SW.2025.15.11

Reasons of Social Exclusion of Elderly Persons

Aristida Čepienė

Šiauliai State Higher Education Institution, Lithuania

E-mail: a.cepiene@svako.lt

https://ror.org/01w69qj84

Nina Grigienė

Mažeikiai District Family and Child Welfare Centre, Lithuania

E-mail: ninagrige@gmail.com

Abstract. The article analyses social exclusion experienced by elderly persons living in one-person households in remote rural areas, its reasons and ways of reducing social exclusion. The qualitative research was conducted by employing the structured interview method, whereas the data collected in the study were processed by using deductive thematic analysis. The results of the study have revealed that the elderly encountered financial difficulties, health problems, lack of household utilities, poor infrastructure of their place of residence, challenges of modern technologies, inaccessibility of services and inequality of their provision, limited public transport, challenges in healthcare institutions, a lack of security, and a lack of information. Social exclusion is determined by low self-esteem, psychological experiences, loneliness, a lack of communication, emigration and the loss of loved ones, as well as absence of close neighbours. It is highly important for elderly persons to keep their homes and live in them as long as possible. In order to reduce social exclusion of the elderly, it is of importance to ensure that they can live in their own homes as long as possible, while being provided social services and help at home as needed. It is also relevant to improve the infrastructure of elderships: organisation and financing of transport, advocacy in contacting banks, healthcare facilities and other institutions, adaptation of the environment and residential premises for the elderly; also, it is essential to install security systems and ensure good condition of roads. To reduce social exclusion, it is fundamental to ensure that elderly people should have the opportunity to communicate, which can be achieved through development of volunteer activities and establishment of a mobile psychological service.

Keywords: social exclusion, elderly persons, one-person household.

Recieved: 2024-10-25. Accepted: 2025-09-29

Copyright © 2025 Aristida Čepienė, Nina Grigienė. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access journal distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

Relevance of the topic. Ageing is a process that takes place throughout a person’s life. Population ageing is a socio-demographic reality of the whole of Europe, posing challenges to social protection and public service systems (Mikulionienė et al., 2018). Elderly persons are those persons who have reached the retirement age and who are unable to independently take care of their personal lives and participate in public life due to their age (Law on Social Services of the Republic of Lithuania, 2006). The National Network of Poverty Reduction Organisations (2020) states that elderly persons living in small villages and isolated hamlets face not only limited access to social services but also limited access to basic services (shops, medical facilities). Due to low income, it is prohibitively expensive for such individuals to reach the said facilities, which is why they encounter major challenges and face an increasing social exclusion. Adomaitytė-Subačienė (2023) confirms that social exclusion includes limited opportunities to use public resources and services, and they are excluded from participation in social life, which is particularly relevant for older people living in remote areas. This situation requires efficient social work tools and strategies to support this group of persons. In this case, social work plays an important role: its purpose is to reduce social exclusion, help elderly persons to maintain their dignity, independence and connections with the community (Ministry of Social Security and Labour, 2024). Home-based social services enable elderly persons to stay in their homes for as long as possible, while maintaining social ties with the family, relatives, society and enhancing their social well-being (Law on Social Services of the Republic of Lithuania, 2006).

Lithuanian researchers analysed social exclusion in general aspects for persons experiencing poverty, the elderly and other target groups (Mikulionienė, 2016). Mikulionienė, Rapolienė and Valavičienė (2018) analysed social exclusion of Lithuanian elderly people living alone in an international context. Bagdonas, Kairys and Zamalijeva (2017) provide exhaustive guidelines for research on old people’s functioning, senility, and ageing. Rapolienė and Tretjakova (2021) analysed the problem of loneliness in the elderly population, while Rapolienė et al. (2017) sought to reveal social exclusion experiences among older people (aged 60 years and older) living alone.

Foreign authors (Dahlberg & McKeea, 2018; Lee, 2021; Cotterell, Buffel, & Phillipson, 2018; Prattley, Buffel, Marshall, & Nazroo, 2020; Urbaniak & Walsh, 2019) examined social exclusion of older people from the European perspective. Lee (2021) analysed how social exclusion affects the subjective wellbeing of elderly people in Europe. Urbaniak and Walsh (2019) explored the effects of interlinked natural and critical life changes on social exclusion among older adults. O’Rourke et al. (2018) analysed interventions and strategies to address loneliness/social connection in older people.

In scientific studies, both Lithuanian and foreign authors (e.g., Mikulionienė, Rapolienė, Lee, Urbaniak, Walsh) analyse the topics of social exclusion among the older population, thereby revealing the aspects of structural, emotional, and institutional support. However, little attention has been paid to elderly persons living in one-person households in remote rural areas, where their experience becomes less visible and understandable.

Research problem. Considering the findings of the study “Provision of Social Services and their Compliance with the Needs of the Population in Municipalities” (2021), it is evident that the planning of municipal social services in rural areas is not sufficiently accurate and oriented towards the specific needs of the population. There is a lack of data on vulnerable population groups, nor are there any clear priorities for the development of social services, which limits the opportunities of elderly persons to receive the appropriate assistance and increases their social exclusion.

The research object: reasons of social exclusion of elderly persons.

The purpose of the research: to find out the reasons of social exclusion of elderly persons living in rural one-person households.

Research samples and participants

The qualitative research was conducted by employing the structured interview method, which can be successfully used as the main method for information collection. This method allows to get to know the subject more thoroughly, to obtain more detailed, open and extensive answers. Structured interviews can also provide a more in-depth understanding of the subjects’ opinion, their feelings, attitude, experience and knowledge, allow to go deep into the perspectives of the research participants, and obtain more abundant data (Flick, 2009). The study involved six elderly persons living in homesteads: three women and three men. The subjects were selected based on a mixed method of purposive sampling: convenience and criterion sampling. Criterion selection was applied, because persons of a similar age (75–95 years old), living in remote rural one-person households that are located 1.5–3 kilometres from the village centre were invited to participate in the study. The research participants are widowed or single, and their adult children live in cities or have emigrated abroad. Convenience sampling was employed, as the research participants were chosen from municipalities that are known to the researchers, but it was sought to ensure the most diverse sociodemographic context possible.

lthough the sample of six individuals is relatively small, the gender balance, different age distribution, marital status, different distances to the centre of the settlement, and varying levels of household utilities help to create the diversity and richness of data, allowing a more exhaustive analysis of the causes of social exclusion in a specific context.

Research methods

The data collected in the study were processed by using deductive thematic analysis according to Braun and Clarke (2019). According to the authors, the said method is flexible, does not have strict boundaries, and can be simulated according to the circumstances of the research being conducted. Data coding was performed by employing latent and semantic codes: semantic codes denoted the direct meaning of the thoughts expressed by the subjects, while latent codes interpreted deeper sociocultural and emotional contexts behind the statements. After the initial code generation, the codes were checked and corrected in several stages. In the first stage, all interview recordings were transcribed, and any personally identifiable data was removed.

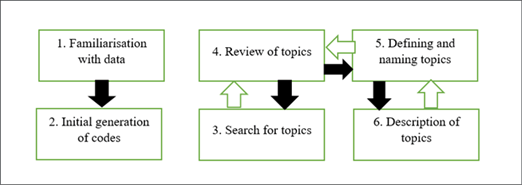

Data saturation was reached when themes and subthemes began to repeat during coding, and newly obtained information no longer provided additional analytical value. This strengthened the reliability of the thematic analysis and justified the generalisation of the research findings. The thematic analysis of the study was performed by using deductive (or theoretical) coding, where both coding and themes are grounded by pre-existing theories related to social exclusion and quality of life of elderly persons (Naeem et al., 2023). The stages of the thematic analysis process (n=6) are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Stages of the thematic analysis of research data

Source: compiled by the authors of the paper, based on Braun and Clarke, 2019

The steps of thematic analysis – from familiarisation with the data to the formation and description of final themes – were implemented according to the six phases outlined by Braun and Clarke (2019) (see Fig. 1). First, the interviews were transcribed, semantic and latent codes were identified, then, the codes were combined into themes and subthemes that reflected the dimensions of social exclusion. Finally, the themes were described, and the data were illustrated with authentic quotes.

The chosen thematic analysis method allows for both flexibility and interpretation in analysing the data, and there are clear steps in the process, which ensure transparency and reliability of the research findings.

Research ethics

The research was conducted in accordance with the research ethics principles of benevolence, voluntariness, informed consent, and confidentiality. The research participants were provided with full information about the study that the information collected about research participants during the interviews would be available only to the researchers. The research participants were assigned fictitious names.

Analysis of the research results

To increase the reliability of data analysis and the consistency of interpretation, we used researcher triangulation in the study: two researchers independently analysed part of the interview transcripts, performed separate coding, and identified preliminary themes. The results were then compared and reconciled. Different interpretations were discussed until a general consensus was reached. Inter-coder agreement was also assessed: coding was repeatedly reviewed by one of the researchers so that to ensure the logical consistency of the themes and their correspondence to the chosen theoretical dimensions of social exclusion. This way, the risk of subjectivity was reduced, and the reliability of the analysis was enhanced.

The deductive thematic analysis involved generation of initial statement codes of the interviews with the research participants, which were grouped into themes with subthemes. The generation of themes was guided by the theoretically analysed dimensions of social exclusion. The paper elaborates on the dimensions of social relations and services, amenities and mobility, which are most relevant for the research participants.

The dimension of social relations

Analysing the dimension of social relations, social relations of elderly persons, which lead to social exclusion, were found out. The theme and subthemes with the assigned initial statement codes, distinguished in this context, are presented in Table 1.

The research aimed to analyse the reasons for living in single-person households. In their old age, elderly persons live alone in their family home. Living alone, the elderly may experience loneliness due to the loss of loved ones. Not all individuals have lost their loved ones, and some live separately due to family circumstances. Jurgis confirms this when he says: “<...> My granddaughter took my wife with her some four years ago... That’s where she is staying <...>” (Jurgis). Loneliness is also influenced by natural human development, when children grow up, leave their homes, start their own families, and parents are left alone to grow old and wait for the ‘sunset’. As it can be observed, children live in different parts of Lithuania: some close to their parents; whereas others live further away. Some close people emigrate in the hope of a better life and leave their old parents alone. Ona says: “<…> One is abroad <...>grandchildren <...> abroad <…>” (Ona). It can be stated that, due to emigration, the elderly face communication barriers with their grandchildren. Bronė confirms this: “<...> We tried here to talk with translations, with everything [laughs], well, but I don’t know... Something didn’t work out for me <...> So, we wave to each other, write to each other, say cheese, cheese and that’s it [laughs]” (Bronė).

Table 1.

The dimension of social relations

|

Themes |

Theme definition |

Sub-themes |

Initial statement codes |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1. Aspects of social exclusion of elderly persons |

Research participants tell about their families, relationships and the provided assistance, the place of residence of their loved ones. They talk about daily difficulties they experience as they grow older and their health declines. Regardless of difficulties, subjects expressed participants felt nostalgic for their youth, denied the present, and talked about preparing for death. All subjects mentioned the importance of communication in their lives. |

Reasons of living in single-person households |

Living alone |

|

Reasons of loneliness |

|||

|

Loved ones living in Lithuania |

|||

|

Emigration of loved ones |

|||

|

The importance of retaining one’s home and maintaining autonomy |

The desire to stay in one’s home |

||

|

The desire to live together with children |

|||

|

Psychological experiences |

Denial of reality and longing |

||

|

Fear of death |

|||

|

Ageing and its challenges |

Declining health and limited mobility |

||

|

The impact of health on everyday life |

|||

|

Primary social network and relationships |

Social circle of loved ones |

||

|

Relationships with loved ones |

|||

|

Visiting loved ones |

|||

|

Socialising with neighbours and friends |

|||

|

The need for communication |

When analysing social relations of elderly individuals, it is of importance to mention the essential aspect of keeping one’s home and maintaining autonomy. The results of the study reveal that all subjects enjoy their homes and see a great meaning of life here. Elderly persons stated that they would like to live with their children only in a critical case of an illness, because they do not want to make life difficult for them. Latent feelings can be discerned in the statements of research participants; i.e., the desire to be with their children and, at the same time, to preserve their autonomy: “<...> I would be satisfied if children were around. Again, on the other hand... I don’t want to be a burden <…> I’m tearing myself apart [laughs] <...>” (Bronė). It can be assumed that elderly persons, due to feeling safe and comfortable at home and wishing to remain autonomous and independent, choose to live alone in their home.

Psychological experiences are another aspect of social relations, which reveals the denial of reality, longing for the past and the perception of loneliness. The research participants state: “<...> I’m now [78 years old], I don’t feel that old... I feel like I’m in my 60s, no more” (Bronė). Loneliness of elderly persons can also increase the fear of death and lead to thoughts about the meaning of one’s life. This feeling is common to other research participants too. Jurgis accentuated: “<...> I’m not afraid to die <…> And as to being alone... Well, I don’t know, if I lose consciousness... I don’t know if I would recover, I can’t tell” (Jurgis). Social ties of elderly persons are significantly affected by ageing, which usually manifests itself by declining health and limited mobility and activeness. Zita emphasises: “<...> I walk a little, potter around the hut, I can’t climb at all, I can’t reach, I can hardly walk <...>” (Zita). It can be assumed that the research participants face various diseases leading to the loss of their autonomy and a reduced quality of life. The health condition can influence daily functioning, such as household chores or interacting with other people. Jurgis regretted that he could no longer work because of his aching legs and arms and his dizzy head: “I feel dizzy. <…> I wouldn’t be sitting now too... But it aches <...>” (Jurgis). As it can be seen from the presented statements, the research participants face physical problems affecting their daily life.

Social relations of elderly persons are significantly affected by relations with the primary social network. The research participants willingly talk about their children and grandchildren. When talking about other loved ones, the subjects were restrained and did not speak. It can be assumed that, in their old age, elderly people communicate most with children and their families, and socialise with others minimally, which is due to the declining health. Most of the research participants get along with their loved ones, but there are cases when they do not communicate with their children. Jurgis states: “I don’t socialise at all... With no one <...> They could kill me <...>” (Jurgis). When analysing Jurgis’ statements, one can get the impression that this family has a lot of grievances against each other, which is why the old man feels rejected and lonely. As it was mentioned above, emigration not only causes the feeling of loneliness but also worsens relationships between loved ones, as the language barrier prevents the elderly from communicating with grandchildren and children’s spouses. Yet, in this context, Zita stated that her daughter-in-law was hostile; although she did help, but she always criticised: “The daughter-in-law grumbles at me a lot <...> everything is messy, she thinks that I can do all housework” (Zita). In addition to good connection of elderly persons with the family and friends, visiting loved ones is also very important. The research participants state: “<...> Grandchildren also don’t forget, they visit me, and bring great-grandchildren to see” (Ona); “Whoever will wish to visit such old... [They] used to visit” (Kazys). As it can be seen, the research participants not only wait for visitors, but, with the help of their children, also go on visits themselves. However, let us consider a statement by Kazys: “But it’s good for me to be at home... I don’t want... It’s best for me to stay at home” (Kazys); hence, it seems that elderly persons often prefer to passively spend their time at home. The statements of the subjects also reveal that they try to justify the infrequent visits of their loved ones. Here, Zita understands: “Children work, they need to earn a living. [My] son doesn’t have time, he comes running here as if a house is on fire <…>” (Zita). Fellowship with neighbours and friends is also integral to the primary social network. Elderly people often feel the need to communicate with others and be socially active in order to reduce the feelings of loneliness. The research participants enjoy good neighbourly relations. Although they do not have any neighbours living nearby, they still know about each other, are interested, and talk on the phone. Jurgis admits: “I don’t socialise with anybody. I don’t know, I don’t need other people’s news” (Jurgis). Here, the person’s possibly hidden closedness and introversion, or the desire to distance oneself from inappropriate persons is highlighted: “Here, not far from here, such drunkards live, they fight, drink <…>” (Jurgis). The research participants also emphasised the lack of communication: “<...> Well, I lack communication a lot [laughs]” (Bronė) and expressed the need for a psychologist: “<...> It would also be good if some psychologist would come occasionally... [pauses to think]. <...> There are such things that you don’t want to say to your loved ones <...>” (Bronė).

Summarising the first topic, it can be stated that elderly persons live in one-person households because they have lost their loved ones or are single, and their children live separately. It is highly important for them to retain their home and stay in it, they want to live with their children only in the critical case of illness. The subjects go through various psychological experiences when thinking about death and preparing for it, although they feel much younger; they would also like to live with their children, although they do not want to burden them with their worries. In addition, elderly persons experience the consequences of ageing (illnesses, reduced mobility), which limit their daily life. Communication is extremely important; they mostly communicate with their children and grandchildren, and they truly value and appreciate communication with their neighbours. It can be assumed that social relations of the elderly are important for their social well-being.

The dimension of services, utilities and mobility

The analysis of the dimension of services, utilities and mobility has revealed challenges encountered by elderly individuals. The elderly are experiencing various difficulties every day, while living in remote rural settlements in one-person households (homesteads). The theme and subthemes with the assigned initial statement codes, distinguished in this context, are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

The dimension of services, utilities and mobility

|

Themes |

Theme definition |

Sub-themes |

Initial statement codes |

|---|---|---|---|

|

2. Challenges faced by old age persons in the areas of service provision, adaptation of utilities and mobility |

Research participants talk about the challenges they face living alone in remote homesteads, their living conditions, the help they receive from their loved ones and neighbours, their attitude towards modern technologies, and the difficulties these technologies are posing. They also tell about the inconveniences experienced in public transport, difficulties in contacting doctors, and the use of self-medication methods. Research participants expressed a negative attitude towards long-term social care, and only very few persons admitted that they wanted to live in social care institutions. |

Challenges experienced in single-person households |

Place of residence |

|

Difficulties experienced |

|||

|

Utilities |

|||

|

Advantages and disadvantages of modern technologies |

|||

|

Public transport |

|||

|

Expectations in the nursing context |

Need for long-term care |

||

|

Avoidance of long-term care |

|||

|

Experiences in healthcare facilities |

Attitude of elderly persons to doctors |

||

|

Challenges of visiting doctors |

|||

|

Self-medication |

|||

|

Provision of informal assistance |

Help from loved ones |

||

|

Help from neighbours |

Life in single-person households can be complicated and challenging for older people. The research participants live in remote one-person households, which are located 1.5 km to 3 km from the nearest village centre. Bronė described her place of residence very vividly: “<...> So you drive through village X, and then you drive to village Z <…> there, I am still about more than one kilometre to the settlement <...> This is a homestead here <…>” (Bronė). The research participants have been living in their homes since birth, or since the creation of their families. It seems that the physical distance to the nearest village centre did not create any significant difficulties, but, instead, only toughened up these individuals. Elderly people living in single-person households may face various difficulties related to the household, utilities, outdoor work and other factors. Ona states: “<...> It is difficult with firewood... <…> it is more difficult with that water that you have to bring <...> I need help to mow a lawn <...> I can’t do it myself” (Ona). Some try to highlight the advantages of living in the village, this way hiding the difficulties they are experiencing. Bronė states: “<...> I am really happy to live in that village... And... Cats [emphasised] live... And there was a dog, <...> and some hens... <…> you don’t need anything else” (Bronė). Ona and Zita singled out the difficulty while shopping; they told: “The shop is three kilometres away, I can’t go there on my own <…>” (Ona). The lack of utilities in the household also causes many challenges. It can be assumed that the poor financial and material situation and the infrastructure of the place of residence prevented individuals from improving their living conditions. Some tried their best to manage their household at least minimally: “<…> In my house, water is supplied from the well” (Jurgis), while others managed according to their personal needs and possibilities: “I have a hydrophore, my husband fixed it when we moved in <...>” (Bronė). Meanwhile, some are still planning: <…> I don’t have any utilities... <…> But maybe I’ll buy this year <...>” (Stasys). Most of the research participants had excuses for themselves why things are the way they are. Kazys said: “<…> First, you know, it’s old construction, there was no sewage system inside. <…> Well, you can’t install so quickly” (Kazys). It was also noticed when conducting the research that the subjects were using old household appliances; this is what Zita says: “<…> That Riga [her washing machine] doesn’t work any longer... so they bought a small one called Maliutka [another brand of washing machines]” (Zita). As stated by the research participants, laundry is one of the most challenging tasks, because they have to wash by hand, or their children help them. It turned out when conducting the study that all research participants had bought solid fuel (firewood), and some of them even for several heating seasons. The advantages and disadvantages of modern technologies can also be attributed to challenges. Modern technologies can make life easier, but, at the same time, they pose new challenges: “I don’t know how, I don’t understand… Everything with that computer. I couldn’t do it on my own, they need all kinds of nonsense now <…>” (Ona). All research participants mentioned that they were using phones: some can only receive calls, whereas others call their children themselves. If the phone is used by every subject, the computer is used only by every sixth research participant. Modern technologies are developing rapidly, which makes it difficult for elderly people to understand and accept them. The research participants stated that they were unable to register with medical institutions, banks, or contact any specialist. Although technologies are improving, there are still areas in Lithuania where telephone and Internet connections are inaccessible to the local residents. Jurgis also states the same: “No, I can’t buy a computer, because <...> there is no Internet... Otherwise I would buy it” (Jurgis). Not only technologies, but also public transport poses challenges for elderly people living in remote single-person households. They experience difficulties related to the accessibility and convenience of public transport. Bronė states: “<…> I have to walk about 4 kilometres to the bus stop <...>” (Bronė). Nor is Ona happy: “The bus stop is half a kilometre away from my home, the polyclinic is also a long way from the bus stop, my health doesn’t allow to walk that much, and I can’t take a taxi, since I don’t have money, my pension is small” (Ona). Public transport schedules are also inconvenient, more tailored to pupils’ needs, they run in the morning and afternoon, and they do not run at all during school holidays. The research subjects tell: “<…> I leave at half past seven, and I have to wait there all day to come home” (Ona); “[School bus]. If children have holidays, the bus doesn’t run at all… Then what remains is neighbours and children” (Bronė). The research revealed that there was a lack of information about the public transport times and directions. The lack of information makes it difficult to reach the distant city. In addition, the immediate environment of the bus stops is not adapted for elderly persons who have physical disabilities. Zita complains: “It’s hard when you have to get in, get out <…>” (Zita). Among all the disruptive challenges, it turned out that there were municipalities where the district’s public transport took passengers for free. Based on the subjects’ statements, it can be stated that elderly people avoid using public transport services and prefer their children’s or neighbours’ help. Stasys even expressed indignation: “These buses are just for the sake of appearances... Well, for children to go... Not for the elderly” (Stasys). There is valid reason to believe that public transport services do not meet the needs of elderly persons.

Elderly persons who are unable to take care of themselves and require constant specialist care may be provided with long-term inpatient care services. The analysis of the provided data revealed the respondents’ expectations for long-term care; therefore, it can be stated that there is a minimal need for this service: only 1 out of 6 research participants wants to be admitted to a long-term care facility. Most are not interested in such supply, are very cautious and timid about long-term care, which seems to evoke unpleasant latent feelings of uselessness, abandonment, and ‘the approaching end’ for the respondents. It can be assumed that elderly people living in remote single-person households prefer to stay in their own homes and choose long-term inpatient care only in an emergency situation, when there is no other option.

The experiences of elderly individuals in healthcare facilities are also an important aspect, as the elderly may have a specific attitude towards doctors and medical services. The analysis revealed that there were research participants who did not visit doctors at all. Here is what Stasys says: “<...> I went to see a doctor some five years ago and that’s all” (Stasys). Zita’s statement: “<…> How can they help me more” (Zita) highlights the subject’s disappointment with doctors, or perhaps the latent role of a victim. Sometimes, elderly persons get tired of the treatment process and start trusting only ‘recommended’ doctors. The research participants are glad that their loved ones accompany them to see doctors and take care of everything as needed. Elderly people face difficulties with registering for a doctor’s appointment. Ona says: “No, I can’t register with a doctor, the doctor’s appointment will be after two or three weeks, or after half a year” (Ona). Sometimes, upon receiving a visit, the subjects are disappointed, because, according to Jurgis: “<...> They say that they don’t have equipment... <...>” (Jurgis), and then, they have to register again for another doctor’s appointment. Elderly people living in remote rural areas are not provided with proper first aid, because paramedics face location challenges. Upon experiencing various difficulties, elderly people become cautious, they self-medicate, look for independent ways to solve health problems, and find out information about possible illnesses from television, mass media, and the circle of their loved ones. It can be assumed that every research participant chooses for himself/herself what treatment method is most acceptable and convenient for him/her.

When analysing challenges faced in the areas of service provision, adaptation of utilities and mobility, informal support provided to elderly persons is also an important aspect. In this context, the coverage of the primary social network providing informal support for the research participants became evident. The elderly receive help in the household: “Girls help, the son-in-law saws firewood, grandchildren stack it up” (Stasys). It can be stated that the participants in the study feel loved and needed, because Zita tells: “<…> They always ask: what do you, grandma, need” (Zita). When analysing the obtained research data, the most prominent was children’s assistance with transportation. The research participants state: “<…> They take me everywhere where I need... my son takes me everywhere” (Zita); “Whenever necessary, they take me to the shop” (Stasys). The research participants feel calm about their future because they trust their loved ones very much. Neighbours are also an important aspect in helping the elderly. The provided help reduces the research participants’ social exclusion and improves their quality of life. Neighbours are most often asked for help with ground work, transportation, and when the elderly want to socialise. Among the research participants, there are also those who are dissatisfied with their neighbours. Jurgis states: “There are no such... I don’t want... I don’t want any neighbours <...>” (Jurgis). Having analysed the aspect of neighbours’ assistance, one can rejoice the presence of friendly neighbourhood, which enriches the lives of elderly persons and fills them with meaning and quality.

To summarise, it can be stated that elderly persons experience various challenges due to their place of residence, lack of utilities, the inability to use modern technologies, and especially due to troubles with public transport. Despite experiencing all inconveniences, the research participants unequivocally choose their own homes rather than living with children or in long-term care institutions. When faced with various challenges arising in medical institutions, elderly people prefer self-medication and folk medicine methods. The quality of life of elderly people is improved by informal help from their loved ones and neighbours.

Discussion

After analysing the aspects of social relations of elderly persons which determine social exclusion, it can be stated that research participants confirm the opinion of Dudutytė and Adamonė (2022) that ageing causes social exclusion. They also agree with the statement of Walch et al. (2017) that the dimension of social relations includes connections with loved ones and neighbours, living in single-person households, and the impact of migration and health. According to Prattley et al. (2020), the increase in social exclusion is significantly affected by poor health of the population, and especially that of men. The data obtained suggest that poor health causes many difficulties to elderly persons. The Law on Social Services of the Republic of Lithuania (2006) regulates the provision of social services to elderly individuals, enabling them to stay in their own homes for as long as possible and to manage their households autonomously. Ambrazevičiūtė (2018) highlighted that elderly persons experienced a strong sense of loneliness due to emigration, and Prattley et al. (2020) stated that social exclusion was significantly influenced by elderly people’s relationships with family, neighbours and friends. On the grounds of analysing the available research data, it can be assumed that the absence of close neighbours causes loneliness among individuals who live in homesteads, and the loss of the loved ones also contributes to this feeling.

After analysing the challenges experienced by elderly people in the areas of service provision, adaptation of utilities and mobility, the research participants confirm the statement of Mikulionienė et al. (2018) that the dimensions of services, utilities and mobility are linked by the geographical location, environmental adaptation, limited public transport as well as dependence on private transport. According to Walsh et al. (2017), healthcare and other types of institutions are becoming difficult for older persons to access due to the lack of information and challenges posed by technologies. The Law on the Fundamentals of Protection of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities of the Republic of Lithuania (2024) ensures adaptation of housing and its environment for elderly persons who have disabilities, but the subjects’ responses show that the lack of household utilities nevertheless remains one of the main problems. A review by the association “National Network of Organisations for Poverty Reduction” (2020) states that, due to a low income, elderly people living in small villages and homesteads find it too expensive to reach the most necessary institutions (the shop, healthcare facility, bank), and therefore they face major challenges and an increasing social exclusion. According to Gečienė and Gudžinskienė (2018), with aging, the need for care increases, and social care becomes an increasingly important part of the social policy, although the majority (5 out of 6) of the research participants reject long-term social care. Considering the results of the study, it can be assumed that the elderly can refuse the offered assistance, since this is justified by the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (2016), which guarantees every person’s right to physical and mental integrity.

Conclusion

The research results allow us to conclude that social exclusion of elderly persons living in one-person households in remote rural areas is determined by complex factors related to social, economic, health, infrastructure, and emotional dimensions. The reasons for social exclusion that emerged most clearly during the study were: living alone, loss of the loved ones or their emigration, health issues, inaccessibility of services and inequality in their provision, limited public transport, a lack of household amenities, low digital literacy, and a lack of information. Social exclusion is also reinforced by psychological experiences, loneliness, a low self-esteem, unwillingness to live in social care institutions, and a strong desire to stay in one’s home.

Taking into account the problems identified in the study, several practical guidelines for reducing social exclusion can be distinguished: it is important to ensure the opportunity for elderly people to live in their homes for as long as possible by providing complex home-based services; to develop infrastructure in elderships, while improving the accessibility of public transport, the condition of roads, the installation of security systems and the adaptation of housing to the needs of elderly persons; to promote the community spirit and volunteerism by creating conditions for volunteer assistance; to establish a mobile psychologist’s service as a way to reduce psychological isolation.

The results of the study are valuable for the development of social policy guidelines, especially in the area of social services development. They reveal the necessity to comprehensively address the problem of social exclusion of elderly persons not only through individual assistance but also through a systemic approach to the planning of services in rural areas.

The findings of the study should be viewed in the light of its limitations. The study involved only six informants, selected through convenience and criterion sampling, which limits the generalisability of the obtained conclusions. Familiarisation with the study sites and the possible selection bias may influence the interpretation of results. The study also did not apply triangulation or double coding for verification of data, which could enhance analytical accuracy.

Considering the results and limitations of the conducted study, it is recommended that future research should expand the analysis to include a larger and more diverse sample of elderly persons, as well as to compare the experiences of rural and urban population. It would be worth applying mixed research methods, supplementing qualitative interviews with quantitative questionnaires, in order to test the prevalence of social exclusion factors in a wider population. It is also essential to explore regional differences in accessibility to services and the impact of social innovation on the quality of life of older people.

This study significantly contributes to the understanding of social exclusion of older people in the rural context, thus highlighting the relevant problems related to maintaining autonomy, accessibility to services, and the fragility of social ties.

Author Contributions. All authors contributed equally to the conception, design, data acquisition, analysis, and writing of this manuscript.

References

Ambrazevičiūtė, K. (2018). Vyresnio amžiaus žmonių teisės į darbą įgyvendinimas visuomenės senėjimo sąlygomis [Enforcement of right to work of older people in ageing society]. [Daktaro disertacija, Mykolo Romerio universitetas [Doctoral dissertation, Mykolas Romeris University]. https://talpykla.elaba.lt/elaba-fedora/objects/elaba:27595137/datastreams/MAIN/content

Bagdonas, A., Kairys, A., & Zamalijeva, O. (2017). Senų žmonių funkcionavimo, senatvės ir senėjimo tyrimų gairės: biopsichosocialinio modelio prieiga [The Guidelines of Researches of Senility, Aging and Functioning of Old People: a Byopsychosocial Approach]. Socialinė Teorija, Empirija, Politika Ir Praktika [STEPP], 15, 80–102. https://doi.org/10.15388/STEPP.2017.15.10811

Braun, V., Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

Cotterell, N., Buffel, T., & Phillipson, C. (2018). Preventing social isolation in older people. Maturitas, 113, 80–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2018.04.014

Dahlberg, L., McKee, K. J. (2018). Social exclusion and well-being among older adults in rural and urban areas. Archives of gerontology and geriatrics, 79, 176–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2018.08.007

Dudutytė, A., Adamonė, D. (2022). Socialinė atskirtis Lietuvoje. Situacijos analizė. Kurk Lietuvai [Social exclusion in Lithuania. Situation analysis. Create for Lithuania]. https://jra.lt/uploads/situacijos-analize-socialine-atskirtis-lietuvoje-2022-1.pdf

Europos Sąjungos pagrindinių teisių chartija [Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union]. (2016). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/LT/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:12016P/TXT&from=EN

Flick, U. (2009). An Introduction to Qualitative Research (4th edition). London: SAGE Publications. https://elearning.shisu.edu.cn/pluginfile.php/35310/mod_resource/content/2/Research-Intro-Flick.pdf

Lee, S. (2021). Social Exclusion and Subjective Well-being Among Older Adults in Europe: Findings from the European Social Survey. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 76(2), 425–434. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbaa172

Lietuvos Respublikos Seimas. Lietuvos Respublikos asmens su negalia teisių apsaugos pagrindų įstatymas [Seimas of the Republic of Lithuania. Republic of Lithuania Law on the Fundamentals of Protection of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities] (galiojanti suvestinė redakcija [current consolidated version] 2024-01-01 – 2025-12-31). https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/TAIS.2319/asr

Lietuvos Respublikos Seimas. Lietuvos Respublikos socialinių paslaugų įstatymas [Seimas of the Republic of Lithuania. Law of the Republic of Lithuania on Social Services] (galiojanti suvestinė redakcija [current consolidated version] 2024-07-01 – 2024-12-31). https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/TAIS.270342/asr

Lietuvos Respublikos socialinės apsaugos ir darbo ministerija [Ministry of Social Security and Labour of the Republic of Lithuania]. (2021). Tyrimo „Socialinių paslaugų teikimas ir jų atitiktis gyventojų poreikiams savivaldybėse“ataskaita [Report on the study “Provision of social services and their compliance with the needs of the population in municipalities”]. https://socmin.lrv.lt/uploads/socmin/documents/files/pdf/SP%20TYRIMO%20ATASKAITA_2021.pdf

Lietuvos statistikos departamentas [Lithuanian Department of Statistics]. (2023). Pagrindiniai šalies rodikliai [Key country indicators]. https://osp.stat.gov.lt/pagrindiniai-salies-rodikliai

Lietuvos statistikos departamentas [Lithuanian Department of Statistics] (2024). Nuolatinių gyventojų skaičius pagal lytį ir amžiaus grupes mieste ir kaime metų pradžioje [Number of permanent residents by gender and age groups in urban and rural areas at the beginning of the year]. https://osp.stat.gov.lt/web/guest/statistiniu-rodikliu-analize?hash=76e9a07e-db64-4315-bc75-99dce4594805#/

Mikulionienė, S. (2016). Lietuvos vyresnio amžiaus žmonių socialinės atskirties rizika: akademinis ir politinis diskursas [The risk of social exclusion among older people in Lithuania: academic and political discourse]. In M. Taljūnaitė (Ed.), Lietuvos gyventojų grupių socialinė kaita [Social change of Lithuanian population groups] (pp. 154–188). Lietuvos socialinių tyrimų centras [Lithuanian Social Research Center]. https://www.lstc.lt/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Socialine_kaita_visas.pdf#page=154

Mikulionienė, S., Rapolienė, G., & Valavičienė, N. (2018). Vyresnio amžiaus žmonės, gyvenimas po vieną ir socialinė atskirtis: monografija [Older people, living alone and social exclusion: a monograph]. Vilnius: Lietuvos socialinių tyrimų centras [Vilnius: Lithuanian Social Research Centre]. https://www.lstc.lt/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/VIENAS1.pdf

Nacionalinis skurdo mažinimo organizacijų tinklas [National Network of Poverty Reduction Organizations]. (2020). Skurdas ir socialinė atskirtis Lietuvoje [Poverty and social exclusion in Lithuania]. https://www.smtinklas.lt/wp-content/uploads/simple-file-list/Metine-skurdo-ir-socialines-atskirties-apzvalga/Skurdas-ir-socialine-atskirtis_2020.pdf

Naeem, M., Ozuem, W., Howell, K., & Ranfagni, S. (2023). A Step-by-Step Process of Thematic Analysis to Develop a Conceptual Model in Qualitative Research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 22, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069231205789

O’Rourke, H., M., Collins, L., & Sidani, S. (2018). Interventions to Address Social Connectedness and Loneliness for Older Adults: a Scoping Review. BMC Geriatrics, 18, Article 214. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-018-0897-x

Prattley, J., Buffel, T., Marshall, A., & Nazroo, J. (2020). Area effects on the level and development of social exclusion in later life. Social science & medicine (1982), 246, Article 112722. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112722

Rapolienė, G., Mikulionienė, S., Gedvilaitė-Kordušienė, M., & Jurkevits, A. (2018). Socialiai įtraukti ar atskirti? Vyresnio amžiaus žmonių, gyvenančių vienų, patirtys [Socially included or excluded? Experiences of older people living alone]. Socialinė Teorija, Empirija, Politika Ir Praktika [STEPP], 16, 70–82. https://doi.org/10.15388/STEPP.2018.16.11441

Rapolienė, G., & Tretjakova, V. (2021). Vienišumo raiška ir veiksniai Lietuvoje bei Europos šalių kontekstas [Expression and factors of loneliness in Lithuania and the context of European countries]. Filosofija, Sociologija. 32(4), 394–406. Lietuvos mokslų akademija [Lithuanian Academy of Sciences]. https://www.lmaleidykla.lt/ojs/index.php/filosofija-sociologija/article/view/4623/3835

Urbaniak, A., & Walsh, K. (2019). The interrelationship between place and critical life transitions in later life social exclusion: A scoping review. Health & place, 60, Article 102234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.102234

Walsh, K., Scharf, T., & Keating, N. (2016). Social exclusion of older persons: a scoping review and conceptual framework. European journal of ageing, 14(1), 81–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-016-0398-8