Social Welfare: Interdisciplinary Approach eISSN 2424-3876

2025, vol. 15, pp. 269–290 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/SW.2025.15.15

Men Devote More Time to Work, While Women Focus on Personal Life?

Viktorija Tauraitė

Vytautas Magnus University, Lithuania

E-mail: tauraiteviktorija@gmail.com

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7045-7570

https://ror.org/04y7eh037

Abstract. The purpose of this study is to examine the empirical content of time allocation between work and personal life among men and women, identifying differences in the average daily time between the two genders. The theoretical aspects of time allocation are analyzed by using comparative literature analysis and summarization methods. Empirical research is conducted by using statistical data analysis, correlation analysis, non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test and data collection methods: survey, time diary and semi-structured expert interview. The target population of this study comprises self-employed individuals in Lithuania.

The results indicate that, from a gender perspective, men allocate most of their daily time to personal life; sleep; other physiological needs; leisure (in a narrow sense); and travel, while women allocate their time primarily to work; household; and family care. This means that women focus on work activities and activities related to the family (in terms of time). On the other hand, men devote more time per day to personal life. The article also examines scientific hypothesis H11: the average daily time allocated to work differs between self-employed men and women in Lithuania; this hypothesis has been rejected.

Keywords: time allocation, personal life, work, self-employed individuals, work-life balance.

Received: 2025-01-28. Accepted: 2025-12-01

Copyright © 2025 Viktorija Tauraitė. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

Time allocation and its effective allocation between work and personal life is a highly relevant topic in the 21st century. Discussions about time allocation and work-life balance are frequently held at both national and international levels. This is supported by previous scientific studies (e.g., Piasna & De Spiegelaere, 2021; Irfan et al., 2023; Bocean et al., 2023; Isa & Indrayati, 2023; Ortiz-Bonnin et al., 2023, and others).

It is obvious that the topic of time allocation for work and personal life is significant both in the context of an individual household and on a national scale. It must be admitted that effective time allocation for work and personal life is a complex task that not everyone is able to successfully cope with. Problems can be caused by personal characteristics, attitude towards work and personal life, the number of children in the family, time planning skills, aspirations, goals, priorities, and more. On the other hand, it is worth focusing on self-employed individuals, for whom, on the one hand, it is relatively easier to independently control the time devoted to work and personal life. On the other hand, the clear and specific boundary between work and personal life is disappearing. Considering these aspects, as well as the increasing relevance of self-employed individuals within the population, this article primarily focuses on self-employed people.

Regardless of gender, both men and women face challenges in time allocation. However, there is often a prevailing stereotype that a woman’s primary role is associated with home care, child-rearing, and similar responsibilities, while men dominate in the professional sphere, striving for career advancement and leadership positions. Therefore, this article emphasizes the peculiarities of time allocation among self-employed individuals, aiming to identify existing similarities and/or differences between men and women.

It is appropriate to conduct an in-depth analysis of the allocation of time between work and personal life in terms of gender at a national level, as it allows for a more accurate, clear and specific analysis of the trends prevailing in a particular country. This article focuses specifically on Lithuania. This decision is not incidental; there is a noticeable lack of such studies in Lithuania. For example, prior to 2000, only a few time allocation studies were conducted in Lithuania (Fisher et al., 2000). As such, time allocation research is not common in Lithuania, and the topic has not been sufficiently explored, despite it being a frequent subject of discussion. Furthermore, in Lithuania, self-employed individuals constituted 11.8% of the employed population in the fourth quarter of 2024 (Official Statistics Portal, 2025). This category of employed individuals is growing and expanding in Lithuania, making the analysis of their time allocation characteristics particularly relevant.

The scientific value of this article can be highlighted at both methodological and empirical levels. From a methodological perspective, it is worth emphasizing that a mixed empirical study is being conducted, which combines aspects of quantitative and qualitative research methods, creating a unique research methodology. The primary methodological aim is related to the accurate and distinctive execution of the study, collecting primary empirical data, and analyzing self-employed individuals in Lithuania regarding their time allocation characteristics. Empirically, the study provides new data on time allocation concerning key areas of time allocation, not only in general terms but also from a gender perspective. Additionally, the empirical data are compared with expert recommendations obtained during this mixed empirical study. Finally, the collected primary data on time allocation for work and personal life provide an opportunity to correctly present the content of the time allocation of self-employed persons in Lithuania both in general terms and from a gender perspective.

Thus, the object of the study is self-employed individuals in Lithuania, focusing on their time allocation for work and personal life, identifying differences and similarities in time allocation between men and women.

Research problem: What is the content of time allocation for work and personal life among men and women?

The aim of the study is to examine the empirical content of time allocation between work and personal life among men and women, identifying differences in the average daily time between the two genders.

The novelty of the research is associated with the creation and implementation of a unique research methodology. At the empirical level, the results of this study contribute to the diversity of research findings and provide an opportunity for a broader and more detailed understanding of a specific category of employed individuals – self-employed persons. Furthermore, the results of this study will complement the field of empirical research on the time allocation for work and personal life in Lithuania and will provide an opportunity to identify the main differences and similarities between men and women in the area of time allocation.

The theoretical aspects of time allocation are analyzed by using comparative literature analysis and summarization methods. The empirical research is conducted by using statistical data analysis, correlational analysis, the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test, and data collection methods such as survey, time diary, and semi-structured expert interview. Thus, from a methodological point of view, a mixed empirical study is conducted. The SPSS software is used for data processing and analysis.

Literature Review

Time allocation between work and personal life

The work-leisure (personal life) model describes the behavior of labor supply participants in the labor market, when individuals’ time is allocated to two main areas: work and leisure (Kool & Botvinick, 2014; Vasilev, 2016; Kabukçuoğlu & Martínez-García, 2016; Bocean et al., 2023; Goenka & Nguyen, 2016; Ortiz-Bonnin et al., 2023, and others). In this article, leisure is used in a broad sense, corresponding to the concept of time dedicated to personal life. In other words, leisure is understood as the time remaining after work, that is, the time allocated to unpaid work, including various forms of leisure activities. This definition of leisure is also utilized by other scholars, including Douglas and Morris (2006), Aguiar and Hurst (2007), Borghans et al. (2014), Eisenhauer (2014), Manski (2014), and others. On the other hand, Aguiar and Hurst (2007) use a narrow definition of leisure. Researchers categorize leisure into four time-related categories: entertainment, relaxation, social activities, and active leisure.

In this article, work time is defined as the time allocated to paid labor. This concept of work time is referenced in time allocation or related studies by researchers such as Aguiar and Hurst (2007), Borghans et al. (2014), Maoz (2010), Bocean et al. (2023), Manski (2014), Kool and Botvinick (2014), and others.

It can be assumed that self-employed individuals find it easier to balance work and personal life, as they have greater control over their time compared to, for example, employed workers. Based on this kind of logic, scholars such as J. I. Gimenez-Nadal et al. (2012), T. Konietzko (2015), M. Knapková et al. (2021), D. J. Agness et al. (2022), M. Knapková (2024) and others, analyze the time allocation characteristics of self-employed individuals between work and personal life.

The need to balance work and personal life is extremely important and relevant in the current context of the modern world, both nationally and internationally. The interest and growing popularity of the concept of work-life balance can be seen in the early 21st century. However, some differences can be identified in the time allocation between men and women.

Characteristics of time allocation between women and men

Men and women may face different challenges in balancing work and personal life (in terms of time). This is also stated by scientists Yokying et al. (2016). According to Bauer et al. (2007), Lajtman (2016), Yokying et al. (2016), Isa and Indrayati (2023), and other authors, balancing work and personal life is simpler for men. One reason for this may be related to an increased integration of women into the labor market in Thailand (Yokying et al., 2016), India (Saha et al., 2016), and, generally, an extensive list of countries worldwide.

Contrasting findings are reported by Hayman and Rasmussen (2013). The researchers find that men experience a lower work-life balance than women. Thus, there is no unequivocal opinion regarding the complexity of balancing work and personal life in relation to gender. On the other hand, differences in time allocation may also depend on the stereotypes expressed in the respective country. For example, in some European countries, the prevailing view is that women should be responsible for the household. Brosch and Binnewies (2018) describe this perspective as traditional. In this case, it should be more challenging for working women to balance work and personal life (Fernandez-Crehuet et al., 2016; Beiler-May et al., 2017).

Guerrina (2015), Fernandez-Crehuet et al. (2016), Yokying et al. (2016), and other authors emphasize that work-life balance for women may also be related to the number of children in the family: the more children there are in the family, the more time should be devoted to home care and children. In this scenario, it should be more difficult for working women to balance work and personal life. On the other hand, Hayman and Rasmussen (2013) do not identify significant differences between men and women, but find that the more children, the more difficult it is to balance work and personal life for both men and women. Representatives of the International Labour Office (2011) emphasize that achieving work-life balance on a national and/or international scale could contribute to reducing gender inequality in the labor market and in the context of personal life.

According to Cowling (2007), balancing work and personal life is important only for women. However, Piasna and De Spiegelaere (2021) emphasize that it is relatively more difficult for women to balance work and personal life due to commitments assumed in both work and family spheres. On the other hand, Yokying et al. (2016) are not so categorical by observing that most often, people with relatively low wages, denoted by a high level of education, but especially women, face difficulties in balancing work and personal life.

Additionally, in the context of time allocation, not only the gender but also the age is important. For example, Aguiar et al. (2018) investigate the characteristics of time spent on work and leisure between men and women but additionally distinguish categories such as younger men and younger women, and older men and older women. Moreover, the characteristics of time allocation between men and women may also depend on work commitments or job specifics, such as the possibility of remote work. These circumstances are further analyzed by Del Boca et al. (2020). This field of research can be supplemented by the findings of the researchers Chung and Van der Lippe (2020): flexible work schedules provide opportunities for both men and women to achieve a better work-life balance. Thus, the characteristics of time allocation can be analyzed from various perspectives.

In conclusion, the discussions and contradictory research results related to the time allocation for work and personal life by gender encourage further research in this area, finding answers about the allocation of time by gender.

Research Methodology

Research methods

In this article, the following methods are applied:

Comparative literature analysis and summarization methods – in order to correctly evaluate the results of the empirical study, it is necessary to review, analyze, and synthesize previous scientific studies in which time allocation was investigated. This allows an objective assessment of the study results within the context of prior research. The method of scientific literature analysis is also used by other researchers (e.g., Bocean et al., 2023; Irfan et al., 2023; Isa & Indrayati, 2023, and others) when analyzing the characteristics of time allocation.

Empirical study focuses on the category of the individually employed population – specifically, on self-employed persons. This decision was made because these individuals have the ability to independently control their time allocation. The flexibility of working hours, especially in achieving work-life balance, is also noted by other scholars, such as Chung and Van der Lippe (2020). Self-employed individuals are defined as employed residents aged 15 and over who may or may not hire employees, do not receive a salary, but earn corresponding income or a share of profits and meet at least one of the following criteria: owning a business; working under a business certificate; or engaging in farming. This definition is based on the State Data Agency (2017).

The in-depth and exploratory analysis of time allocation is conducted in Lithuania. This decision is not arbitrary, as there is a noticeable deficiency of such studies within the country. For example, prior to 2000, only a few time allocation studies had been conducted in Lithuania (Fisher et al., 2000). Thus, time allocation research is infrequent in the Lithuanian context, and the topic is not sufficiently developed, even though time allocation and related phenomena are frequent subjects of discussion. Additionally, in the fourth quarter of 2024, self-employed individuals constituted 11.8% of the employed population in Lithuania (Official Statistics Portal, 2025). This category of employed individuals has been growing and expanding in Lithuania, thereby making the analysis of their time allocation characteristics particularly relevant.

Statistical data analysis is essential for comparing the data under study, identifying the prevailing trends and critical aspects. This method has also been used by other researchers (e.g., Knapková, 2024; Piasna and De Spiegelaere, 2021, and others), whose object of study is the time allocation or related characteristics. This method is used in this study to analyze empirical data from a survey, a time diary, and a semi-structured expert interview.

Correlation analysis is a useful method for identifying the presence of statistical or non-statistical relationships between variables. It is used by other researchers (e.g., Agness et al., 2022; Gimenez-Nadal et al., 2012; Irfan et al., 2023, and others) to study time allocation or related aspects. Correlation analysis is used in this study to identify the relationships between: (1) the number of children in the family and the average amount of time spent on family care per day; (2) the number of children in the family and the ranking of family care (priority of time allocation area according to importance); (3) the average amount of time spent on sleep and the average amount of time spent on family care; work per day; (4) the average amount of time spent on sleep per day and the average monthly net income; (5) the average amount of time spent on work per day and the average amount of time spent on science/studies; household; family care; leisure per day; (6) the average amount of time spent on science/studies per day and the average amount of time spent on family care; leisure per day; (7) the average amount of time spent on household per day and the average amount of time spent on family care; leisure; travel per day; (8) the average amount of time spent on family care per day and the average amount of time spent on leisure; travel per day. For correlation analyses, Pearson’s, Spearman’s, and Kendall’s tau-b correlation coefficients were utilized with a 95% confidence level.

The nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test is used to compare two independent groups and determine if they come from the same population by comparing their ranked values. This method is used in this study to examine the following hypotheses: (1) the average daily time devoted to work differs between self-employed men and women in Lithuania; (2) net monthly income differs between self-employed men and women in Lithuania. More details of these scientific hypotheses are described at the end of this section.

Primary data collection methods: survey, time diary, and semi-structured expert interview. To conduct the most up-to-date statistical data analysis in the field of time allocation and to analyze time allocation data from various aspects, it was decided to collect primary data in accordance with international standards and the essential principles of the prevailing methodology. The survey was chosen to identify the respondents’ needs, knowledge about the main principles of time allocation, and net income. These aspects are important for examining the content characteristics of time allocation. Researchers (e.g., Clark et al., 2010; Borghans et al., 2014; Balducci et al., 2016, and others) also use survey in the context of time allocation research.

Methodologically, the survey was developed based on the Harmonized European Time Use Survey (HETUS, 2007) and contributions from the author of the study. Structurally, the questionnaire consisted of seven sections (control questions; respondent’s needs; satisfaction with work, personal life and aspects of happiness; respondent’s knowledge of the economics of happiness, concepts and basic principles of time allocation; wages; substitution/income effect; demographic questions). Due to the limited scope of this article, only a part of the empirical data from the survey will be analyzed. The main focus will be on the respondent’s needs, knowledge of the basic principles of time allocation, and salary.

The time diary is most used to identify individuals’ behavior in the context of time allocation. In this study, the time diary was chosen to identify the respondents’ average time-allocation patterns for corresponding time allocation domains. This method in the field of time allocation is also used by other researchers, such as T. DeJonge et al. (2016), E. Brosch and C. Binnewies (2018), and others.

From a methodological point of view, the time diary was filled out by respondents over two calendar days: one working day and one day off. The time diary identified the following primary areas of time allocation: sleep; other physiological needs; work; study/education/self-education; household; family care; leisure, travel, and other activities. These time allocation areas were identified based on the methodological aspects of HETUS (2007). The main aim of the time diary methodological instrument is to collect empirical data on the average daily time values of self-employed individuals, which are allocated to the relevant area of time allocation.

The respondents for the survey and time diary were self-employed individuals in Lithuania.

Semi-structured expert interviews are typically used to identify in-depth, expert-type insights in the study domain. In this study, a semi-structured expert interview was chosen to identify time allocation features and recommendations in the analyzed domain. This method in the field of time allocation is also used by other scholars such as W. De Wet et al. (2016), C. Lyonette (2015), and others.

The semi-structured expert interview was structured in six main areas: area of expertise; type of expert; time allocation; job satisfaction, personal life and happiness aspects; links between time allocation and happiness; demographic questions. Due to the limited scope of this article, the primary focus will be on the characteristics of time allocation and the recommendations identified by the experts.

The informants for the semi-structured expert interviews were experts from eight categories (which were identified and correspondingly linked to the relevant areas of time allocation): medicine; healthy lifestyle; economics and business; education and science; social sciences; culture; transportation; politics and law. The interview data were analyzed by using content analysis. The main criteria for selecting experts were their field of expertise and work experience (at least 5 years).

The primary data collected using the survey, time diary, and interview methods are interpreted as average data reflecting the relevant category being analyzed, including areas of time allocation. The data collection period was from September 2, 2019, to November 30, 2019. Conducting a mixed empirical study using survey, time diary and semi-structured interview requires a lot of time, knowledge and opportunity resources. Therefore, this article is based on empirical data from 2019, which is planned to be repeated in the future for comparative data analysis.

The survey data representatively reflect the self-employed population in Lithuania with a probability of 97%. A total of 1073 surveys and time diaries were found to be valid. The survey and time diary data were matched based on these five criteria: type of economic activity; county; the gender; age and type of individual. This article will primarily focus on the general results of self-employed individuals and their characteristics by gender.

A total of 48 experts participated in the semi-structured expert interviews (six from each identified category). The most common tenure among experts was 5 years (14.6%), 20 years (12.5%), and 30 years (10.4%).

Data processing and analysis were conducted by using the SPSS software. Statistically, the respondent who answered the survey and time diary questions was most often a person working in the services sector (51.4%), living in the Vilnius region (71.5%), male (60.9%), falling within the 25–54 age category (71.5%), and seeking to balance work and personal life (72.6%). The majority of experts interviewed were from Vilnius County (79.2%), with a gender distribution that was similar: 52.1% female and 47.9% male. Most interviews were conducted with individuals seeking to balance work and personal life (77.1%).

Scientific hypothesis

This article tests scientific hypothesis using a significance level of 0.05.

H11: the average daily time allocated to work differs between self-employed men and women in Lithuania.

This hypothesis shall be confirmed if the average daily time allocated to work by self-employed men and women significantly differs statistically, with p < 0.05. A non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test is applied.

The standard gender stereotype of time allocation is most prevalent: men spend relatively more time on work, and women on their personal lives. From this statement, it can be assumed that men should spend relatively more time on work than women. Consequently, the average daily time spent on work between men and women should differ statistically significantly.

The combination of all applied empirical methods enables a broader, more comprehensive, and more accurate examination of the content of time allocation between men and women, highlighting the most important aspects.

Results and Discussion

Key insights on the importance of general and time allocation areas for men and women

Across genders, the three main areas of time allocations remain consistent with the overall findings (respectively: women; men): work (33.6%; 35.8%); family care (27.4%; 27.0%); sleep (18.8%; 20.4%; see Table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of time allocation area by importance of self-employed persons in Lithuania

|

Priorities |

General |

Gender |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Ranks |

Self-employed persons |

Ranks |

Men |

Ranks |

Women |

|

|

Work |

1 |

34.9% |

1 |

35.8% |

1 |

33.6% |

|

Caring for the family |

1 |

27.1% |

1 |

27.0% |

1 |

27.4% |

|

Sleep |

1 |

19.8% |

1 |

20.4% |

1 |

18.8% |

|

Other physiological needs |

4 |

20.4% |

4 |

22.2% |

3 |

23.8% |

|

Housework |

5 |

19.2% |

5 |

19.3% |

5 |

19.0% |

|

Leisure |

6 |

23.3% |

6 |

21.9% |

6 |

25.5% |

|

Travel |

7 |

48.1% |

7 |

47.0% |

7 |

49.8% |

|

Science/studies |

8 |

74.4% |

8 |

73.4% |

8 |

76.0% |

|

Other activities |

9 |

99.5% |

9 |

99.7% |

9 |

99.3% |

Note. Leisure is used in a narrow sense. ‘1’ indicates the most significant area of time allocation; ‘9’ indicates the least significant area of time allocation. Percentages are provided for each area of time allocation separately (indicating the most frequently chosen response option); thus, the total exceeds 100%.

Nevertheless, it has been observed that that, for women, taking care of the family is more important, while for men, work and sleep are more important. This reflects classical gender stereotypes: women allocate their primary role to family, while men focus on work. Additionally, this argument can be substantiated by the differences in the number of children respondents have in their families based on gender. For example, the majority of women report having two children (44.8%), whereas a significant proportion of men report having no children (40.7%). It is understandable that having more children in the family necessitates devoting more time to family care. This can be supported by the results of a correlational analysis indicating a statistically significant relationship (p < 0.05) with 95% confidence between the number of children in the family and the average daily time devoted to family care, although the correlation is very weak (ρ = 0.131). In other words, the more children one has in the family, the more time is devoted to family care (or vice versa).

These research findings are consistent with those obtained by Fagan et al. (2012). In such situations, family care often becomes a priority compared to other areas. These insights are confirmed by a correlational analysis showing a statistically significant relationship (p < 0.05) with 95% confidence between the number of children in the family and the rank assigned to family care (according to its importance among all areas of time allocation), although the relationship is weak (ρ = -0.203). In other words, the more children one has in the family, the lower is the rank assigned to family care within the time allocation areas (or vice versa). Considering the fact that the lower is the rank assigned to the respective area of time allocation, the more important the time allocation area is, it can be concluded that the more children there are in a family, the more important the time allocation area related to taking care of the family (or vice versa). Therefore, no significant differences in the ranking order among the most important areas of time allocation were identified based on gender. Conversely, certain areas of time allocation are more important (in terms of frequency of choice) for women, while others are more important for men.

Among self-employed individuals in Lithuania in 2019, women (earning 801–1000 euros: 30.2%) more frequently earn more than men (earning 701–900 euros: 29.6%). However, this gender wage gap is not statistically significant. This is supported by the fact that, with 95% confidence, the monthly net income received by men and women does not significantly differ (p > 0.05). This indicates that the monthly net income does not statistically differ between self-employed men and women in Lithuania.

Nevertheless, the monthly net income received by both women and men does not meet their expectations. Both women (46.4%) and men (47.2%) are typically willing to work an additional hour (01:00) to achieve their desired level of monthly net income.

Both women (96.4%) and men (94.9%) are aware of the recommendations regarding the time allocation between work and personal life. However, women accumulated greater knowledge in this area. This may be attributed to personality traits such as curiosity and inquisitiveness, etc. To accurately identify potential causes in this case, a more comprehensive study would be required.

Characteristics of time allocation content between men and women

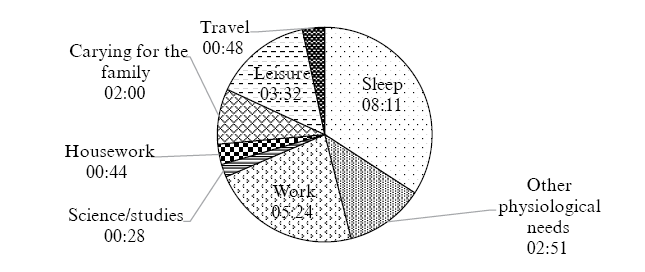

In 2019, self-employed individuals in Lithuania allocated an average of 77.5% of their daily time to personal life, while 22.5% was dedicated to work (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Structure of daily time allocation for self-employed individuals in Lithuania in 2019

Note. Leisure is used in a narrow sense. No time is allocated for other activities. Due to rounding, there may be a deviation of up to 00:02 hours.

In detailing the time allocation of Lithuanians in 2019, it should be noted that, in the context of personal life, the majority of daily time is allocated to sleep (34.1%), leisure (in a narrow sense; 14.7%), and other physiological needs (11.9%; see Figure 1).

Time for work and personal life. Self-employed individuals in Lithuania spend on average 77.5% of their daily time to personal life and 22.5% to work (see Figure 1). Assessing the ratio between time spent on work and personal life, it can be said that this ratio is positive. The opposite situation, according to Makabe et al. (2015), would be identified if the time spent on work exceeded the time spent on personal life.

With 95% confidence, logical associations have been established between time allocated to work and other areas of time allocation. It has been determined that the more time is allocated to work, the less time is allocated to sleep (ρ = -0.364); to science/studies (ρ = -0.180); to household (ρ = -0.214) and to family care (ρ = -0.288; the cause-and-effect relationship may be of an opposite nature). It has been identified that, with 95% confidence, there exists a statistically significant (p < 0.05), but weak (ρ = -0.306), negative relationship between the average daily time allocated to work and the time allocated to leisure (in a narrow sense). Similar results were obtained by Fuess (2006) in his analysis of the Japanese labor market.

In summarizing the connections between time allocated to work and other areas of time allocation, it is important to note the findings by Lajtman (2016): the more time is allocated to work, the more frequently work-life conflict is identified. According to Aziz and Cunningham (2008), long working hours contribute to workaholism. Therefore, long working hours unbalance the optimal allocation of time and can ultimately lead to a number of negative consequences.

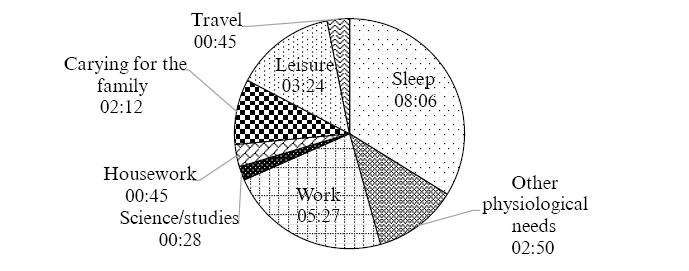

A similar proportion of time allocated to work and personal life is observed when analyzing respondents by gender (women: 77.2% for personal life, 22.8% for work; men: 77.6% for personal life, 22.4% for work; see Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2.

Time allocation structure of self-employed women in Lithuania in 2019

Note. Leisure time is used in a narrow sense. No time is allocated for other activities. Due to rounding, there may be a discrepancy of up to 00:03 hours.

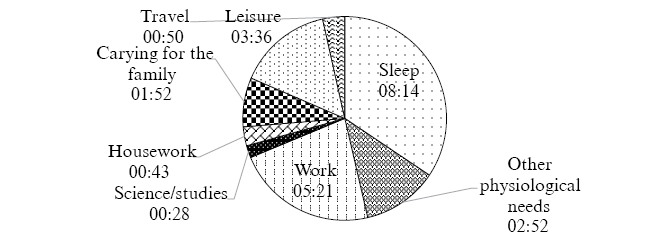

On the other hand, men allocate more time (by 00:05 hours) daily to personal life, whereas women devote more time to work. This fact contradicts the classical time allocation between genders, as emphasized by Rubiano-Matulevich and Kashiwase (2018). According to the results of that study, men dominate in the sphere of personal life, while women dominate in the workplace (in terms of time allocation). On the other hand, upon testing Hypothesis H11, it was rejected (p > 0.05). This indicates that, on average, the time allocated to work does not differ between self-employed men and women in Lithuania.

Figure 3.

Time allocation structure of self-employed men in Lithuania in 2019

Note. Leisure time is used in a narrow sense. No time is allocated for other activities. Due to rounding, there may be a discrepancy of up to 00:04 hours.

Brunnich et al. (2005), Booth and Van Ours (2007) and other researchers, including Ramey and Francis (2009), have established that the time allocated to work tends to increase over time. This increase is associated with a rise in the time that women spend on work, while the time that men spend on work has decreased. Nevertheless, Yokying et al. (2016) emphasize that long working hours are a serious issue among women. All of this has a negative impact on health and productivity. Differences in time allocation for work between men and women are not always identifiable. For example, Burke and El-Kot (2009) find that men and women allocate a similar amount of time to work. In contrast, Snir and Harpaz (2006), Fagan et al. (2012), Hamermesh (2019) and other researchers find out that women allocate more time to personal life than men.

However, in terms of time allocated to personal life, the dominant areas of time are sleep (33.8% for men; 34.4% for women) and leisure (in a narrow sense; 14.2% for men; 15.0% for women; see Figure 3). This actual time allocation contradicts the areas of time allocation indicated by the respondents, according to their importance: in the area of personal life, the most important areas for both men and women were caring for the family and sleeping time allocation (see Table 1 for more details). This situation may have arisen because both men and women perceive family care as the most important aspect of personal life, but practical realities dictate that sleep becomes the primary area of time allocation within personal life. Furthermore, in practice, the importance of leisure (in the narrow sense) is noticeable, which was not distinguished among the most important areas of time allocation. Nevertheless, both men and women allocate the least time daily to science/studies (1.9% for both) and other activities (0% for both; see Figure 2 and Figure 3). This actual time allocation aligns with the ranking of time allocation areas according to the respondents’ perceived importance. However, there are noticeable contradictions between the identified areas of time allocation according to importance and the actual time allocation. In this situation, the research presented in this article is extremely important.

Time allocated to personal life: sleep. Self-employed individuals allocate, on average, the most time to sleep within the personal life area – 34.1% (08:11 hours; see Figure 1). The time allocated to sleep falls within the recommendations of medical experts (within a range from 06:30 hours to 09:00 hours). However, allocating less than 06:00 hours of sleep per day, according to Masaitienė and Sakalauskaitė-Juodeikienė (2018), Sakalauskaitė-Juodeikienė and Masaitienė (2018), and the European Society of Cardiology (2018), may lead to various health issues over time. Nevertheless, the time allocated to sleep shows a decreasing trend: in the 20th century, the average daily time allocated to sleep decreased from approximately 09:00 hours to 06:05 hours. All this justifies the need for a more detailed analysis of time allocation.

It has also been established with 95% confidence that the less time is allocated to sleep, the more time is devoted to family care (ρ = -0.141; the cause-and-effect relationship may be of an opposite nature). However, sleep is often the area of time allocation that compensates for the lack of time for other activities. This aspect is also emphasized by Williams (2008).

It has been determined with 95% confidence that there is a statistically significant (p < 0.05) but weak (ρ = -0.364) negative correlation between the average daily time allocated to sleep and the time allocated to work. It would be a mistake to assume that spending less time for sleeping and more time for working will ultimately result in a higher net monthly income. Based on the correlation analysis, it has been found with 95% confidence that there is a statistically insignificant (p > 0.05) correlation between the average daily time allocated to sleep and the net monthly income. However, the researchers Gibson and Shrader (2015), studying the labor market in the USA from 2003 to 2013, delivered the opposite findings: in the short term, an increase of 01:00 hour in weekly sleep duration results in a 1% increase in the employee wages, while in the long term, it results in a 4.5% increase.

It has been found that men allocate more time to sleep daily than women (difference: 00:08 hours; see Figure 2 and Figure 3). Thus, minimal gender differences are identified in this aspect. On the other hand, Hamermesh (2019) indicates that there is no difference between the genders regarding the time allocated to sleep.

Time allocated to personal life: other physiological needs. Self-employed individuals allocate, on average, 02:51 hours per day to other physiological needs (such as eating, personal hygiene, etc.; see Figure 1). The actual time allocated to other physiological needs aligns with the recommendations of healthy lifestyle experts (ranging from 01:15 hours to 03:15 hours).

In terms of gender, minimal differences are observed: men allocate 0.2 percentage points more time daily to other physiological needs than women (see Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Time allocated to personal life: science/studies. Self-employed individuals allocate, on average, 00:28 hours daily to science/studies (see Figure 1). According to education and science experts, insufficient time is allocated to science/studies. The time allocated to this area should be increased by at least 00:22 hours per day (recommendation is given to devote from 00:50 hours to 02:40 hours). So, there is a need to adjust the time allocated to science/studies.

Connections between the time allocated to science/studies and other time allocation areas have been identified. With 95% confidence, it has been determined that the more time is allocated to science/studies, the less time is devoted to work (ρ = -0.180); family care (ρ = -0.078); leisure (in a narrow sense; ρ = -0.274; the cause-and-effect relationship may be of an opposite nature).

There are no differences between the genders regarding the time allocated to science/studies, as both women and men allocate, on average, 00:28 hours daily to this time allocation area (see Figure 2 and Figure 3). However, Hamermesh (2019) indicates existing gender differences in the time allocated to science/studies: women allocate more time to this area than men.

Time allocated to personal life: household. Self-employed individuals allocate, on average, 3.1% of their daily time, or 00:44 hours, to household (see Figure 1). However, the time allocated to household and its importance are often overestimated. This can be substantiated by the fact that these individuals most frequently rank household as the fifth most important area of time allocation (at 19.2%; see Table 1). On the other hand, based on actual data on the amount of time spent on household by self-employed individuals, it was found that this area of time allocation is in seventh place. This indicates that the time allocated to household is perceived as more important by individuals than the amount of time they can actually afford to devote to it. Nevertheless, the time allocated to household per day falls within the recommended time interval specified by social experts (within a range from 00:30 hours to 03:10 hours).

It has been identified that the household area is related to other time distribution areas. With 95% confidence, it has been established that the more time is allocated to household, the more time is dedicated to family care (ρ = 0.113); less to work (ρ = -0.214); leisure (in a narrow sense; ρ = -0.134); and travel (ρ = -0.169; the cause-and-effect relationship may be of an opposite nature).

In terms of gender, minimal differences are noted: women allocate 0.1 percentage points, or 00:02 hours, more time daily to household than men (see Figure 2 and Figure 3). This indicates a relatively similar distribution of roles within the household when performing household chores. On the other hand, Rubiano-Matulevich et al. (2019) indicate that women allocate more time to household than men.

Time allocated to personal life: family care. Self-employed individuals allocate, on average, 8.3%, or 02:00 hours per day, to family care (see Figure 1). However, there are noticeable contradictions: respondents most commonly (27.1%) indicate that this is one of the most important areas of time allocation in terms of importance, but, in terms of time allocated, this area of time allocation is in the fifth place. This only confirms the fact that relatively insufficient time is allocated to family care. According to recommendations from social experts, the time allocated to family care area falls within the recommended limits (suggested from 01:00 hours to 09:30 hours).

Connections between family care and other time allocation areas have been established. With 95% confidence, it has been determined that the more time is allocated to family care, the more time is devoted to household as well (ρ = 0.113), but less to sleep (ρ = -0.141); work (ρ = -0.288); science/studies (ρ = -0.078); leisure (in a narrow sense; ρ = -0.360); and travel (ρ = -0.091; the cause-and-effect relationship may be of an opposite nature).

Women allocate, on average, 1.4 percentage points more time daily to family care than men (see Figure 2 and Figure 3). In this case, the classic time allocation model is evident: women dominate in the area of family care, while men dominate in the work sphere. Similar findings are reported by Rubiano-Matulevich et al. (2019). However, the results of this study are not entirely typical of previous research or prevailing stereotypes. As previously mentioned, it has been established that women allocate more time to work, while men allocate more time to personal life. Additionally, women also allocate more time to family care than men.

Time allocated to personal life: leisure (in a narrow sense). Self-employed individuals in Lithuania allocate, on average, 14.7% of their daily time, or 03:32 hours, to leisure (in a narrow sense; see Figure 1). Internationally, differences are noted. For example, Wei et al. (2016) indicate that, in studies of the labor markets in China, the USA, and Japan, relatively the most time for leisure (in a narrow sense) is allocated in the USA, while the least is allocated in Japan.

When analyzing the labor market of self-employed individuals in Lithuania, discrepancies between the importance and the duration of time allocated again become apparent. Leisure (in a narrow sense) is identified as the sixth most important area (see Table 1). However, in terms of time allocated, this time allocation area can be classified as ranking the fourth (see Figure 1). This means two possibilities: 1) too much time is allocated to leisure (in a narrow sense); 2) the importance of leisure (in a narrow sense) is undervalued. Based on the recommendations of cultural experts, it is likely that the first scenario applies, as the duration of time allocated to leisure (in a narrow sense) exceeds the maximum limit recommended by experts (advisable from 00:47 hours to 02:55 hours).

Connections between leisure (in a narrow sense) and other time allocation areas have been identified. With 95% confidence, it has been determined that the more time is allocated to leisure (in a narrow sense), the less time is devoted to the household (ρ = -0.134); work (ρ = -0.306); science/studies (ρ = -0.274); and family care (ρ = -0.360; the cause-and-effect relationship may be of an opposite nature). Similar, but relatively stronger, relationships have been identified between the average daily time allocated to leisure (in a narrow sense) and the time allocated to work (ρ = -0.306); science/studies (ρ = -0.274); and family care (ρ = -0.360). The results of this study coincide with the conclusions of the analysis by Wei et al. (2016): in China, the USA, and Japan, a negative correlation exists between the time allocated to leisure (in a narrow sense) and the time allocated to science/studies and work. Fuess (2006) also identifies a negative correlation between work and leisure (in a narrow sense). The findings of this research allow to say that there are relevant connections between leisure (in a narrow sense) and other time allocation areas.

Men allocate 0.8 percentage points more time daily to leisure (in a narrow sense) than women (see Figure 2 and Figure 3). Nonetheless, leisure (in a narrow sense) is one of the reasons that men allocate more time to personal life than women. The results of this study align with those of other researchers: Fuess (2006), Gálvez-Muñoz (2011), Rubiano-Matulevich et al. (2019), and others. For example, Fuess (2006) found that women allocate less time to leisure (in a narrow sense) than men.

Time allocated to personal life: travel. Self-employed individuals allocate, on average, 3.3% of their daily time to travel (i.e., 00:48 hours; see Figure 1). Discrepancies are again noted. The actual time allocation data for travel fall within the limits of expert recommendations (advised as from 00:18 hours to 00:52 hours).

Men allocate 0.4 percentage points more time daily to travel than women (see Figure 2 and Figure 3). This is logical, as men allocate more time to personal life than women, and travel is one of the time allocation areas that fall within personal life.

Time allocated to personal life: other activities. Self-employed individuals do not allocate time to other activities (see Figure 1). Although experts indicate that individuals should allocate between 00:05 and 01:25 hours to other activities, it is evident that this condition is not being met.

Thus, self-employed individuals in Lithuania allocate an average of 22.5% of their daily time to work and 77.5% to personal life. In terms of gender, men spend most of their time per day on personal life; sleep; other physiological needs; leisure (in a narrow sense); and travel, while women focus on work; household and family care. This means that women focus on work activities and activities related to the family (in terms of time allocation). Thus, in numerical terms, it was found that women spend more time on work than men, but, in statistical terms, no significant differences were identified.

Conclusions

The analysis of scientific literature reveals that the work-leisure (personal life) model characterizes the behavior of participants in the labor market regarding the allocation of time to work and personal life. The time allocated to work is understood as the total time spent on work activities while time spent on personal life includes all the remaining time of the day. Scientists analyze the time allocation between work and personal life from various perspectives. One of the objects of research may be the gender aspect. Some researchers argue that time allocation is relatively more complex for women, whereas others contend that women face greater challenges in time allocation. Given these and other nuances, it is essential to investigate the content of time allocation between men and women more broadly and comprehensively, aiming to identify the key differences and similarities between men and women.

From a methodological point of view, self-employed individuals in Lithuania are the target group of this research. The focus is on the content of time allocation between men and women, conducting mixed empirical research. More precisely, the study was conducted by using statistical data analysis, correlational analysis, the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test, and various data collection methods: survey, a time diary and semi-structured expert interview.

Across genders, the three main areas of time allocation remain consistent with general trends: work; family care; and sleep. Overall, the average net monthly income differs numerically for self-employed men (€701–900) and women (€801–1000). Statistical analysis indicates that the distribution of net monthly income for self-employed men in Lithuania does not significantly differ from that of self-employed women (p > 0.05).

On average, self-employed individuals in Lithuania allocate 22.5% of their daily time to work and 77.5% to personal life. A similar time allocation also dominates in terms of gender. Women allocate an average of 77.2% of their daily time to personal life and 22.8% to work, while men allocate 77.6% to personal life and 22.4% to work. However, upon testing H11, it was rejected (p > 0.05). This indicates that the average daily time allocated to work does not differ between self-employed men and women in Lithuania. Thus, in numerical terms, it was found that women spend more time on work than men, but, in statistical terms, no significant differences were identified.

In terms of gender, men spend most of their time per day on personal life; sleep; other physiological needs; leisure (in a narrow sense); and travel, while women focus more on work; household and family care. This means that women focus on work activities and activities related to the family (in terms of time allocation). On the other hand, men spend more time on personal life. This fact contradicts classical time allocation models between genders, and the results of this study provide an opportunity for further in-depth analysis and discussion regarding the content of time allocation between men and women.

A mixed empirical study on the content of time allocation of self-employed men and women in Lithuania has identified the following similarities and differences in terms of gender. Similarities include that both men and women allocate an average of equal time per day to science/studies (00:28 hours) and other activities (no time allocated, i.e., 00:00 hours per day). Differences indicate that men allocate more time to sleep (difference: 00:08 hours), other physiological needs (difference: 00:02 hours), leisure (in a narrow sense; difference: 00:12 hours), and travel (difference: 00:05 hours), whereas women allocate more time to work (difference: 00:06 hours), household (difference: 00:02 hours), and family care (difference: 00:20 hours).

The main limitations of the study are associated with methodological aspects. Methodologically, the content and structure of the questionnaire and time diary used to achieve the aim of this study were adjusted and modernized, compared to the methodological instruments used in HETUS. Furthermore, the primary empirical data from the questionnaire and time diary were collected over a three-month period rather than a full year, as was done in the case of the HETUS. Thus, this research could be improved by adjusting the research methodology in order to reduce the limitations of the study.

Future research may explore various aspects of the phenomenon of time allocation alongside other relevant dimensions. For example, the characteristics of time allocation content across age categories, types of economic activity, and residential locations could be investigated. The focus could shift to analyzing the causes and consequences at a macroeconomic level, both nationally and internationally. Additionally, a similar study could be conducted in a different base country and with a different population.

The scientific contribution of this study lies at the methodological and empirical levels. From a methodological perspective, it is worth emphasizing that a mixed empirical study is being conducted, which combines aspects of quantitative and qualitative research methods, creating a unique research methodology. Empirically, the collected primary data on time allocation for work and personal life provide an opportunity to correctly present the content of the time allocation of self-employed persons in Lithuania both in general terms and from a gender perspective.

References

Aguiar, M., Bils, M., Charles, K. K., & Hurst, E. (2018). Leisure luxuries and the labor supply of young men (February 22, 2018). Retrieved January 13, 2025, from https://econ.la.psu.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2023/05/leisureluxuriesfeb212018_updated.pdf

Aguiar, M., & Hurst, E. (2007). Measuring trends in leisure: The allocation of time over five decades. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122(3), 969–1006. https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.122.3.969

Auerbach, A. J., & Hassett, K. A. (2022). Valuing the time of the self-employed (NBER Working Paper No. 29752). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w29752

Aziz, S., & Cunningham, J. (2008). Workaholism, work stress, work-life imbalance: exploring gender’s role. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 23(8), 553–566. https://doi.org/10.1108/17542410810912681

Bauer, F., Groß, H., Oliver, G., Sieglen, G., & Smith, M. (2007). Time use and work–life balance in Germany and the UK. Anglo-German Foundation for the Study of Industrial Society. https://web.archive.org/web/20170314012836/http://www.agf.org.uk/cms/upload/pdfs/R/2007_R1453_e_time_use_and_work-life_balance.pdf

Beiler-May, A., Williamson, R. L., Clark, M. A., & Carter, N. T. (2017). Gender Bias in the Measurement of Workaholism. Journal Of Personality Assessment, 99(1), 104–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2016.1198795

Bocean, C. G., Popescu, L., Varzaru, A. A., Avram, C. D., & Iancu, A. (2023). Work-Life Balance and Employee Satisfaction during COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability, 15(15), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511631

Booth, A. L., & van Ours, J. C. (2007). Job satisfaction and family happiness: The part-time work puzzle (Discussion Paper No. 2007-20). Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA). https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/91984/1/2007-20.pdf

Borghans, L., Collewet, M., Seegers, P. (2014, June 15-16). Measuring preference for leisure using hypothetical choices [Conference presentation]. 14th journées Louis-André Gérard-Varet Conference, Aix-en-Provence, France.

Brosch, E., & Binnewies, C. (2018). A Diary Study on Predictors of the Work-life Interface: The Role of Time Pressure, Psychological Climate and Positive Affective States. Management Revue, 29(1), 55–78. https://doi.org/10.5771/0935-9915-2018-1-55

Brunnich, G., Druce, P., Ghissassi, M., Johnson, M., Majidi, N., Radas, A. L., Riccheri, P. R., De Sentenac, C., & Vacarr, D. (2005). Three case studies of time use survey application in lower and middle-income countries. Institute of Political Studies of Paris (Sciences-Po). https://web.archive.org/web/20220119145016/http://www.levyinstitute.org/undp-levy-conference/papers/paper_Vacarr.pdf

Burke, R. J., & El‐Kot, G. (2009). Work intensity, work hours, satisfactions, and psychological well‐being among Egyptian managers. Education, Business and Society: Contemporary Middle Eastern Issues, 2(3), 218–231. https://doi.org/10.1108/17537980910981787

Chung, H., & van der Lippe, T. (2020). Flexible Working, Work–Life Balance, and Gender Equality: Introduction. Social Indicators Research, 151(2), 365–381. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-018-2025-x

Cowling, M. (2007). Still at work? An empirical test of competing theories of the long hours culture (IES Working Paper No. WP٩). Institute for Employment Studies. https://www.employment-studies.co.uk/system/files/resources/files/wp٩.pdf

de Wet, W., Koekemoer, E., & Nel, J. (2016). Exploring the impact of information and communication technology on employees’ work and personal lives. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology/SA Tydskrif vir Bedryfsielkunde, 42(1), Article a1330. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v42i1.1330

DeJonge, T., Veenhoven, R., Kalmijn, W., & Arends, L. (2016). Pooling Time Series Based on Slightly Different Questions About the Same Topic Forty Years of Survey Research on Happiness and Life Satisfaction in The Netherlands. Social Indicators Research, 126(2), 863–891. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-0898-5

Del Boca, D., Oggero, N., Profeta, P., & Rossi, M. (2020). Women’s and men’s work, housework and childcare, before and during COVID-19. Review of Economics of the Household, 18, 1001–1017. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-020-09502-1

Douglas, E. J., & Morris, R. J. (2006). Workaholic, or just hard worker? Career Development International, 11(5), 394–417. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620430610683043

Eisenhauer, J. G. (2014). Labor supply with Friedman-Savage preferences. Studies in Economics and Finance, 31(2), 186–201. https://doi.org/10.1108/SEF-08-2012-0095

European Society of Cardiology. (2018, August 27). Finding the sweet spot of a good night’s sleep: not too long and not too short [Press release]. Retrieved January 14, 2025, from www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2018/08/180826120746.htm

Fagan, C., Lyonette, C., Smith, M., & Saldaña-Tejeda, A. (2012). The influence of working time arrangements on work-life integration or ‘balance’: A review of the international evidence (Conditions of Work and Employment Series No. 32). International Labour Office. https://www.auca.kg/uploads/Migration/digest_26/04.pdf

Fernandez-Crehuet, J. M., Gimenez-Nadal, J. I., & Reyes Recio, L. E. (2016). The national work-life balance index©: the European case. Social Indicators Research, 128(1), 341–359. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-1034-2

Fisher, K. (2000). Exploring new ground for using the Multinational Time Use Study (IEA Discussion Paper No. 2000-28). Institute for Economic Analysis. https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/92133/1/2000-28.pdf

Fuess, S. M., Jr. (2006). Leisure time in Japan: How much and for whom? (Discussion Paper No. 2002). Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA). https://docs.iza.org/dp2002.pdf

Gálvez-Muñoz, L., Rodríguez-Modroño, P., & Domínguez-Serrano, M. (2011). Work and Time Use By Gender: A New Clustering of European Welfare Systems. Feminist Economics, 17(4), 125–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2011.620975

Gibson, M., & Shrader, J. (2015). Time use and productivity: The wage returns to sleep [Working paper]. Williams College, Department of Economics. https://web.williams.edu/Economics/wp/GibsonShrader_Sleep.pdf

Gimenez-Nadal, J. I., Molina, J. A., & Ortega, R. (2012). Self-employed mothers and the work-family conflict. Applied Economics, 44(17), 2133–2147. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2011.558486

Goenka, A., & Nguyen, M. -H. (2016). General existence of competitive equilibrium in the growth model with an endogenous labor-leisure choice and unbounded capital stock. Conference Paper of the Vietnam Economist Annual Meeting 2016, Article 78. https://veam.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/109.-Manh-Hung-Nguyen.pdf

Guerrina, R. (2015). Socio-economic challenges to work-life balance at times of crisis. Journal of Social Welfare and Family Law, 37(3), 368–377. https://doi.org/10.1080/09649069.2015.1081223

Hamermesh, D. S. (2019). Spending Time: The Most Valuable Resource. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Harmonised European Time Use Survey (HETUS). (2007). Main Activities. Retrieved January 14, 2025, from https://web.archive.org/web/20190309212710/https://www.h6.scb.se/tus/tus/StatMeanMact1.html

Hayman, J., & Rasmussen, E. (2013). Gender, caring, part time employment and work/life balance. Employment Relations Record, 13(1), 45–58. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.529048508948948

International Labour Office. (2011). Work–life balance. http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_norm/---relconf/documents/meetingdocument/wcms_163642.pdf

Isa, M., & Indrayati, N. (2023). The role of work–life balance as mediation of the effect of work–family conflict on employee performance. SA Journal of Human Resource Management/SA Tydskrif vir Menslikehulpbronbestuur, 21(0), Article a1910. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajhrm.v21i0.1910

Kabukçuoğlu, A., & Martínez-García, E. (2016). The market resources method for solving dynamic optimization problems (Working Paper No. 274). Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, Globalization and Monetary Policy Institute. https://dx.doi.org/10.24149/gwp274

Knapková, M. (2024). Work-life dynamics: Comparing time use of employees and self-employed individuals in Slovakia. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 10, Article 101177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2024.101177

Knapková, M., Martinkovičová, M., Kaščáková, A. (2021). Time Allocation And Feelings Of Happiness Of Self-Employed Persons – A Gendered Perspective. ACC Journal, 27(2), 63–72. https://doi.org/10.15240/tul/004/2021-2-006

Konietzko, T. (2015). Self-Employed Individuals, Time Use, and Earnings. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 36, 64–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-014-9411-6

Kool, W., & Botvinick, M. (2014). A labor/leisure tradeoff in cognitive control. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 143(1), 131–141. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031048

Lajtman, M. K. (2016). Impact of personal factors on the work life conflict and its co-influence with organizational factors on employee commitment in Croatia [Doctoral dissertation, University of St. Gallen]. https://www.bib.irb.hr:8443/1265489/download/1265489.MirnaKL-PhDThesis.pdf

Lyonette, C. (2015). Part-time work, work–life balance and gender equality. Journal of Social Welfare & Family Law, 37(3), 321–333. http://doi.org/10.1080/09649069.2015.1081225

Makabe, S., Takagai, J., Asanuma, Y., Ohtomo, K., & Kimura, Y. (2015). Impact of work-life imbalance on job satisfaction and quality of life among hospital nurses in Japan. Industrial Health, 53(2), 152–159. https://doi.org/10.2486/indhealth.2014-0141

Manski, C. F. (2014). Identification of Income-Leisure Preferences and Evaluation of Income Tax Policy. Quantitative Economics, 5(1), 145–174. https://doi.org/10.3982/QE262

Maoz, Y. D. (2010). Labor Hours in The United States and Europe: The Role of Different Leisure Preferences. Macroeconomic Dynamics, 14(2), 231–241. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1365100509090191

Masaitienė, R., & Sakalauskaitė-Juodeikienė E. (2018). Nemiga. Ką svarbu žinoti [Brošiūra].

Official Statistics Portal. (2025). Employment and unemployment [Data set]. State Data Agency (Statistics Lithuania). https://osp.stat.gov.lt/statistiniu-rodikliu-analize#/.

Ortiz-Bonnin S, Blahopoulou J, García-Buades ME, Montañez-Juan M. (2023). Work-life balance satisfaction in crisis times: from luxury to necessity – The role of organization‘s responses during COVID-19 lockdown. Personnel Review, 52(4), 1033–1050. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-07-2021-0484

Piasna, A. & De Spiegelaere, S. (2021). Working Time Reduction, Work-Life Balance and Gender Equality. Dynamiques régionales, 10(1), 19–42. https://shs.cairn.info/revue-dynamiques-regionales-2021-1-page-19?lang=en.

Ramey, V. A., & Francis, N. (2009). A century of work and leisure. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 1(2), 189–224. https://doi.org/10.1257/mac.1.2.189

Rubiano-Matulevich, E., & Kashiwase, H. (2018, April 18). Why time use data matters for gender equality—and why it’s hard to find. Data Blog. https://blogs.worldbank.org/opendata/why-time-use-data-matters-gender-equality-and-why-it-s-hard-find.

Rubiano-Matulevich, E., Viollaz, M., & Walsh, C. (2019, September 9). Time after time: How men and women spend their time and what it means for individual and household poverty and wellbeing. Data Blog. https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/opendata/time-after-time-how-men-and-women-spend-their-time-and-what-it-means-individual-and

Saha, A. K., Chaudhuri, S., & Mazumdar, S. S. (2016). Work-Life Balance of Women Teachers in West Bengal. Indian Journal of Industrial Relations, 52(2), 217–229. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44840810

Sakalauskaitė-Juodeikienė, E., & Masaitienė, R. (2018). Naujas nemigos apibrėžimas, etiopatogenezė, diagnostikos ir gydymo algoritmas. Neurologijos seminarai, 22 No.3(77), 164–173. https://www.journals.vu.lt/neurologijos_seminarai/en/article/view/27824/27058

Snir, R., Harpaz, I. (2006). The workaholism phenomenon: a cross-national perspective. Career Development International, 11(5), 374–393. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620430610683034

State Data Agency. (2017). Savarankiškas darbas [Metainformacija]. https://osp.stat.gov.lt/documents/10180/0/savarankiskas+darbas_metainfo.

Vasilev, A. (2016). Aggregation with a mix of indivisible and continuous labor supply decisions: The case of home production. International Journal of Social Economics, 43(12), 1507–15012. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSE-04-2015-0098

Wei, X., Huang, S. S., Stodolska, M., & Yu, Y. (2015). Leisure time, leisure activities, and happiness in China. Journal of Leisure Research, 47(5), 556–576. https://doi.org/10.18666/jlr-2015-v47-i5-6120

Williams, C. (2008). Work-life balance of shift workers. Perspectives on Labour and Income [Catalogue no. 75-001-X], 9(8), 5–16. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/75-001-x/2008108/pdf/10677-eng.pdf

Yokying, P., Sangaroon, B., Sushevagul, T., & Floro, M. S. (2016). Work-life balance and time use: lessons from Thailand. Asia-Pacific Population Journal, 31(1), 87–107. https://doi.org/10.18356/1a175191-en