Taikomoji kalbotyra, 22: 36–58 eISSN 2029-8935

https://www.journals.vu.lt/taikomojikalbotyra DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Taikalbot.2025.22.3

Nijolė Tuomienė

Institute of the Lithuanian Language

nijole.tuomiene@lki.lt

ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6662-4615

Abstract. The study, based on empirical data collected at the beginning of the 21st century from 17 Lithuanian Language Atlas (LLA) points in the Šalčininkai district, aims to answer several questions: Under what circumstances did the local identity of multilingual people form and why did a significant group of people in the region choose to call themselves as locals (Lith. tuteišiai, Bel. тутэйшыя, мясцовыя, Pol. tutejszy, miejscowy)? The study aims to reveal the current consequences of this previously accepted choice of the population. After analysing sociolinguistic surveys of residents, recorded group discussions, and in-depth interviews with respondents, it can be stated that most respondents who call themselves locals, identify themselves as Poles. Most of the older villagers interviewed speak the Belarusian dialect po prostu (Eng. simple speech) in everyday life, the middle generation communicates mainly in Russian and Polish, and the younger generation communicates mainly in Polish, Russian, and Lithuanian.

Qualitative data analysis showed that the concept of identity of different generations of residents of Southeastern Lithuania is constantly changing, albeit slowly and insignificantly. The boundaries of ethnic identities in the region remain unclear. The processes of identity change in the Šalčininkai district have not yet been completed. Poles in the district often describe their regional identity with other categories, which determine identification with local areas. The study allows us to predict that regional local identity is gradually decreasing, and other forms of identification are strengthening, primarily ethnic (more characteristic of the middle generation of residents) and civic (more characteristic of the younger generation of residents) identities.

Keywords. Southeastern Lithuania, local identity, the line between “local” and “non-local”, ethnic identity, Belarusian dialect “po prostu” (Eng. simple speech)

Santrauka. Straipsnyje pagrindinis dėmesys sutelkiamas į Pietryčių Lietuvos gyventojų vietinės tapatybės formavimosi aspektus. Ieškoma sąsajų tarp istorinių aplinkybių nulemtos gyvenamos teritorijos valstybinės priklausomybės kaitos ir vietos gyventojų identiteto. Tyrimo, paremto XXI a. pradžioje iš 17 Lietuvių kalbos atlaso (LKA) punktų Šalčininkų rajone surinkta empirine medžiaga, tikslas – atsakyti į kelis klausimus: kokiomis aplinkybėmis susiformavo daugiakalbių gyventojų vietinis identitetas ir kodėl nemaža regiono gyventojų grupė pasirinko vadintis tuteišiais (brus. тутэйшыя, мясцовыя; l. tutejszy, miejscowi). Tyrimu siekiama atskleisti dabartines šio anksčiau priimto gyventojų pasirinkimo pasekmes.

Išanalizavus sociolingvistines vietos gyventojų apklausas, įrašytus grupinius pokalbius ir giluminius interviu, galima teigti, kad didžioji dalis Šalčininkų rajono gyventojų, kurie save vadina vietiniais, tuteišiais ar čionykščiais, save laiko lenkais. Dauguma apklaustų vyresniosios kartos kaimo gyventojų kasdieniame gyvenime kalba baltarusių tarme po prostu, vidurinės kartos žmonės dažniausiai bendrauja rusiškai ir lenkiškai, o jaunosios kartos – lenkiškai, rusiškai ir lietuviškai.

Kokybinė duomenų analizė parodė, kad skirtingų kartų Pietryčių Lietuvos gyventojų tapatybės samprata nuolat kinta, nors lėtai ir nežymiai. Regione išlieka etninių tapatybių ribų neaiškumas. Užbaigtų tapatybės kaitos procesų Šalčininkų rajone dar nėra. Savąjį regioninį identitetą rajono lenkai dažnai apibūdina kitomis kategorijomis, nusakančiomis tapatinimąsi su lokaliomis vietovėmis. Tyrimas leidžia prognozuoti, kad vyksta laipsniškas regioninio vietinio (lokalinio) tapatumo nykimas ir kitų identifikavimo formų, pirmiausia etninio (būdingesnio vidurinei gyventojų kartai) ir pilietinio (būdingesnio jaunesniajai gyventojų kartai) tapatumo stiprėjimas.

Raktažodžiai. Pietryčių Lietuva, vietinė (tuteišių) tapatybė, riba tarp „vietinio“ ir „nevietinio“, etninė tapatybė, baltarusių tarmė „po prostu“

____________

Copyright © 2025 Nijolė Tuomienė. Published by Vilnius University Press.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use,

distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Southeastern Lithuania is a unique region of the Lithuanian state. As a borderland where Baltic and Slavic cultures, Catholicism, and Orthodoxy merge, this region inevitably acquires specific features compared to the rest of the country. Thus, intensive processes of identity change have taken place and are still ongoing in the whole Southeastern Lithuanian border region. This is particularly evident when it comes to the change of the so-called local identity. In the last decade of the 20th century, researchers of Southeastern Lithuania (e.g., Garšva, Grumadienė 1993 (ed.); Daukšas 2008: 53–68; Korzeniewska 2013: 169–177; Šliavaitė 2015: 27–51; Marcinkevičius 2016a: 22–34, Vyšniauskas 2020b: 29–47) recorded a significant number of people who identified themselves without specifying their ethnic identity, instead referring to themselves as locals (Lith. tuteišiai, Bel. тутэйшыя, Pol. tutejszy). Historical events, when Southeastern Lithuania was taken as a spoil for other countries, undoubtedly played a role in this.

This paper uses the term Southeastern Lithuania, which is already well established in scientific literature, due to the historical rather than geographical concept of this region. Today’s Southeastern Lithuania is a border region, distinguished from the rest of the country primarily by its ethnic composition and the active multilingualism of its population, where the status of the Lithuanian language is the weakest. Standard Lithuanian is used in official communication only when it is absolutely necessary.

The inhabitants of the Šalčininkai district in Southeastern Lithuania do not associate or identify themselves with the population to the north of Vilnius city, in the northern part of the present-day Vilnius district. Therefore, the data collected in those areas were not included in this study, as it was considered more appropriate to analyze the data from the north of the Vilnius district separately and from a different perspective. The main difference between these two relatively small regions is in the spoken languages, since, unlike the southeastern part, the northeastern area is predominantly Polish with no Belarusian spoken (Čekmonas, Grumadienė 1993: 108–114; Czekmonas 2017: 115–127).

It is very important to conduct research in this region, during which, based on scientific methods, data would be collected and analyzed about the people living here, their self-perceptions, attitudes, relations with the Lithuanian state, and other ethnic groups living here. When analyzing complex identity problems, the author of the work takes the position that it makes the most sense to let people define their identity themselves, without imposing any categories on them in advance. In this way, it is possible to obtain the most accurate information possible about who the residents of Southeastern Lithuania consider themselves to be, and how and why they construct such an identity.

The aim of the study is to determine the specifics of the construction of local identity among the inhabitants of Southeastern Lithuania and answer the question: Does local identity transition into ethnic (or other) identity? Based on the latest empirical data, the study intends to describe the boundary they draw between their “own” geographical space and the rest of Lithuania, and reveal the concept of localness (so-called Tuteishness, meaning “of local origin”) that still exists in the region. The object of the research is the local identity of the current inhabitants of Southeastern Lithuania. The investigation is based on empirical data collected at the beginning of the 21st century from 17 points of Lithuanian Language Atlas (Lietuvių kalbos atlasas, LLA) as part of a geolinguistic and sociolinguistic survey covering the whole of Lithuania1. The inhabitants of these 17 points were multilingual; most of them spoke Belarusian (so-called po prostu, meaning “simple speech”) in their everyday life, had varying levels of proficiency in Polish and Russian, and a few, especially the younger ones, spoke Lithuanian.

The complexity of the study is reflected in the following objectives:

1. To determine whether there is a link between: a) the change in the state affiliation of the inhabited territory due to historical circumstances; and b) the deliberate avoidance of the population to declare their ethnic or even state identity.

2. To reveal why a significant group of the region’s population has long identified themselves as Tuteishy (“locals”) (Bel. тутэйшыя, мясцовыя; Pol. tutejszi, miejscowi) and what the present-day consequences of this earlier choice are.

3. To identify the factors influencing the choice or dominance of one language over another.

The article analyzes three types of data: 1) targeted responses of local residents to a sociolinguistic questionnaire (83 questionnaires completed); 2) recorded interviews between the researcher and local residents (total 71 hours); 3) recorded dialogues between local residents in the course of active code-switching (27 hours long). When necessary, the data are compared with the corresponding audio recordings from the Dialect Archive dating back to 1964–19902.

The informants represent three generations: the older generation (60–95 years old), the middle generation (40–59 years old), and the younger generation (18–39 years old). The largest number of respondents were from the older generation (37). These people are permanent residents of the study area, and many of them are used to communicating in two or even three languages specific to the region, freely switching between at least two of them. Interviews of 29 middle-generation informants and their responses to the abovementioned sociolinguistic questionnaires were recorded. Most of the people of this generation understood Lithuanian, but not all of them could speak it.

During the interviews, the interviewees were free to choose the language that they felt most comfortable with and were accustomed to using at home. In rural areas, Belarusian (they call it po prostu, meaning “simple speech”) was more commonly chosen by the older generation, while the middle generation reported often speaking two local dialects at home, both Polish and Belarusian (po prostu), sometimes switching to Russian. Lithuanian was used the least during the interviews, typically only in more formal, situational contexts, and usually only by younger people.

Out of the 17 representatives of the younger generation, only nine agreed to express their opinion on the region’s complex historical periods, the languages characteristic of the region, and the specifics of their use. Even fewer, only six of them, shared their opinion on the ethnic identity of the local population, and described the concept of Tuteishy.

Not all interviewees were willing to answer questions on values. Across the three generations of informants, the older generation provided the most information on identity, while some of the younger generation’s stories were quite fragmentary, though still informative. Some of the recorded interviews (31) could be described as incidental: they were unplanned and spontaneous conversations with the people we met, during which the worldview of the locals was revealed. One thing is clear: in the southeastern region of Lithuania, it is important to periodically update the ethnolinguistic and sociolinguistic research, especially on the change and interaction of languages (codes), which would summarize the data from a given period on the self-perception of the people of the region, the situation of multilingualism, and the attitudes towards the past or present. The facts of this type provide this study with undeniable relevance and novelty.

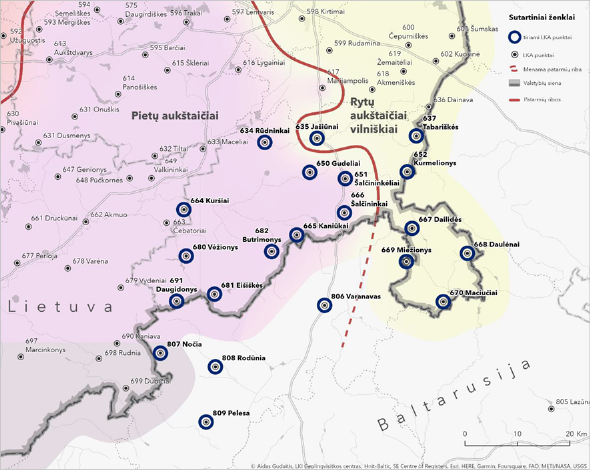

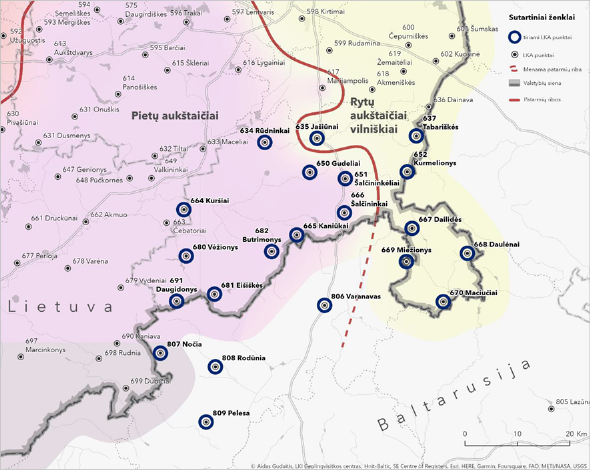

The presence of local identity in the region is confirmed by interviews with residents and their recollections of the past, in which larger settlements, towns and cities are mentioned. The mentioned places were used to draw the boundaries of what people perceive as their land. Eventually, it turned out that the areas they considered to be their own land included some of what is now Belarus. This proves another important point: not long ago, the regions of Southeastern Lithuania and Northwestern Belarus were a single territory inhabited by Lithuanians, and the inhabitants of both countries are still linked to each other by various interconnections (see Figure 1; Vyšniauskas 2020a: 90–94; Tuomienė 2023: 77–83).

The data were analyzed using a qualitative research method. The data were obtained by means of interviews and consisted of monologues by individual presenters and group dialogues. In a natural multilingual environment, the aim was to find out the respondents’ views on what determines one or another sociolinguistic human behavior. The study also aimed to find out the most important factors in the ethnolinguistic assessment of the situation in which they live, and to identify the factors that they consider the most significant in shaping it.

This qualitative study uses the following sociolinguistic methods of surveying residents:

1) “Group conversation” (free communication), which took place outdoors (over 27 hours of group dialogues recorded). Residents of various ages participated in it. Interview participants communicated spontaneously and naturally. The conversations were conducted in Belarusian, Polish, Russian, and Lithuanian (several languages were used at the same time).

2) “Detailed interview” (detailed survey), when one elderly resident was selected and interviewed in more detail (31 respondents were surveyed). According to the qualitative research methodology, the experience of such an informant reflects the general situation in the areas under study. The survey was conducted in the language chosen by the speaker: most often Belarusian and Polish.

3) “Semi-structured interview” (sociolinguistic survey of respondents), when informants were consistently asked questions from the sociolinguistic questionnaire (83 questionnaires completed). The survey was conducted in the language in which the informant communicated in everyday life.

At this point, it is necessary to recall the theory of biographical narratives, according to which researchers must trust the people who tell the stories, because they usually have no way of verifying their veracity. It is important for the researcher to sense what the speaker does not say (leaves between the lines) and what he or she deliberately emphasizes, which memories and stories are passed down from generation to generation in the community, and which are deliberately omitted and forgotten over time. It is important to note that this work focuses on the oral traditions of the people of the region, distancing itself from institutions and their interpretations of the past. It does not look at how various narratives entered social memory, e.g., through oral historical-cultural memory, the media, or other sources.

It is important to note that this study analyzes the most recent population data from the beginning of the 21st century. Due to the lack of comparable data from the entire Vilnius region, which includes Northwestern Belarus, it was decided to focus on the data from the Šalčininkai district of Southeastern Lithuania. Sufficient data were collected through geolinguistic and sociolinguistic research (Mikulėnienė, Meiliūnaitė (eds.) 2014). They correlate with memories recorded in the middle and late 20th century, which testify to how the Lithuanian language was deliberately and systematically pushed out of all areas of usage, ultimately almost disappearing from the list of four languages spoken in the region (cf. Volkaitė-Kulikauskienė 1987; Zinkevičius 1993, 2005; Tuomienė 2017: 788–826).

In the 20th century, as the administrative affiliation of the state changed several times, the ideology of the state changed accordingly. As a result, the inhabitants of Southeastern Lithuania did not have the opportunity to pass on the historical narrative of their origins from one generation to the next, as it was constantly adjusted to suit the interests of the government and the church (cf. Savukynas 2003: 88–91; Daukšas 2012: 167–193). For the last few centuries, Polish identity has been consolidated here not by language, but by the ideology of power, reinforced by confessional affiliation: if you are Catholic, you are Polish (cf. Korzeniewska; 2013: 164–166; Čekmonas 2017 [1995]b: 80–85; Tuomienė 2023: 89–92). Under such conditions, the local identity of the Belarusian-speaking (po prostu) population was formed.

Sociologist Fredrik Barth was one of the first to formulate a definition of an ethnic group and to study the processes of creating and maintaining ethnic boundaries between groups. In his book Ethnic Groups and Boundaries, published in 1969, Barth stresses that the object of study should not be the cultural traits of a particular group, but how people perceive the difference, the boundary, between themselves and others. The essence of the ethnic boundary is the identification of a person with a culture and people who are considered “their own” and the distancing from others regarded as “foreign”. This perception of difference persists even when people migrate from one culture to another (Barth 1969: 9–10, 14).

Thus, according to Barth, people draw boundaries between communities of people with different identities based on criteria such as: (1) language, dress, lifestyle, and (2) fundamental value orientations (moral norms). Identity-based boundary drawing has a profound effect on people’s everyday behavior. People tend to interact and develop relationships with people from their own culture, i.e. people with similar identities, and avoid contact with people from other cultures (with different identities) (Barth 1969: 15).

Based on these findings by Barth, it can be argued that ethnic differences between groups persist due to the perception and maintenance of these differences in social interaction, rather than due to actual cultural differences. This aligns with the perspective expressed by the people of Šalčininkai: “people here speak differently than people in Lithuania”.

Two other prominent scholars, Andreas Wimmer and Marcus Banks, argue that Barth’s criteria for dividing people into ethnic groups are vague, as people are allowed to belong to several groups at the same time or move from one group to another (Wimmer 2008: 976). In other words, people who interact with people from other ethnic groups in different situations have a vague idea of what constitutes their “own” ethnic group versus what is “foreign”. This is because the real cultural differences that can distinguish between these two groups are not clearly defined. For example, the residents of Butrimonys do not distinguish between Belarusian-speaking Belarusians and Poles, as the residents of both nationalities are Catholic and speak the same languages.

The interpretations of ethnic identity, the formulation of definitions, and the ideas and generalizations developed in the work of these three scholars have contributed to shaping the conceptual framework of this research.

When analyzing the data, it was important to find out what criteria residents choose when describing their ethnic or other distinctiveness and comparing themselves with the rest of the Lithuanian population. We should bear in mind the fact previously established by researchers that all people living in Southeastern Lithuania primarily emphasize the difference between their defined territory (their land) and other areas of Lithuania. A crucial factor is the differences in the languages used by ethnic groups living on the border and in other areas of Lithuania.

These criteria were brought to light by another scholar of ethnicity and identity, Anthony Smith, in his The Ethnic Origins of Nations, published in 1986. This scholar identifies, much more clearly than Barth, a number of important criteria for drawing the boundary between the own/foreign and the local/non-local: memories, language, collective names, origin stories (myths), a shared sense of history (the past), and a shared culture, which is certainly different from the others, an attachment to a specific territory and its geographic location, and a sense of solidarity within the group (Smith 1986: 2–29).

The theoretical insights developed by Smith are useful when considering how and to what extent people living in Southeastern Lithuania are involved in the field of national symbols. Do the majority of Poles in the region try to identify themselves with the symbols that represent the Lithuanian civic community? The acceptance or rejection of these symbols that unite the entire Lithuanian civic nation may be closely linked to the ethnicity of the people living in the Šalčininkai region.

These insights are confirmed by the research data, as some of the speakers mentioned the threat of “denationalization”, and therefore continuously emphasized their defensive ethnicity, which they believe protects them against denationalization. Based on these insights, one can question and seek answers as to why some people born and raised in Southeastern Lithuania choose to emphasize ethnic boundaries (local Poles) while others choose to highlight national boundaries (local Lithuanians). Why is it important for some to emphasize ethnic identity, for others national identity, and for others civic identity, while the fourth group of the population remains undecided?

Another prominent sociologist, Rogers Brubaker, in his book Ethnicity Without Groups (2004), discusses ways in which ethnicity can be analyzed without dividing people into closed groups. The author argues that our perception that ethnic groups exist as such is not accurate, since the division of people into ethnic groups cannot be automatic (Brubaker 2004: 3–12). Human relations should not be understood in terms of static groupings, but as a constantly changing and dynamic process.

Andreas Wimmer, in his book Ethnic Boundary Making. Institutions, Power, Networks (2013), suggests that scholars studying ethnicity should answer several questions before analyzing empirical data and summarizing research findings: (a) whether the ethnic community is identified by ethnicity or by other criteria (do not confuse community solidarity with ethnicity); (b) the researcher whose object of study is the ethnic boundary must be cautious and ethical in his/her assessment of those people who consciously choose not to identify with, or even to distance themselves from, the particular ethnic group from which they originate (Wimmer 2013: 42–43).

The studies discussed here force us to rethink two important aspects of the identity development of the inhabitants of Southeastern Lithuania: 1) their perception of the past and the present of the area they live in, and 2) what they consider to be their local identity now.

In contemporary society, ethnic identity is one of the collective identities that refers to an individual’s identification with an ethnic group: a shared religion, traditions, collective self-understanding, culture, and language (Naumenko 2012). Previous studies have uncovered a range of conceptions of identity, showing that in Europe, identity was related to the historical environment, so it was common for societies to simply assign identity. While some researchers reveal a strong link between ethnicity and nationality, others argue that identity, in general, is constructed, so people are increasingly inclined to associate and identify with several ethnic groups (Barth 1969; Smith 1986; Neumann 1999). Ethnic, national, and cultural identities are often equated in the search for a link between culture, ethnicity, and distinctiveness (see Eriksen 2002: 100; Bauman & Gingrich 2004).

Researchers analyze ethnic (as well as national) identity as one of the areas of a person’s identity, when a person can describe himself or herself and clearly answer the question: Who am I? (Leonavičius 1999: 33–44; Antinienė 2002: 100–107). The most appropriate definition of identity for this study was that of John Hutchinson and Anthony D. Smith (Hutchinson, Smith 1996: 7): ethnic identity is a sense of commonality within a group or community, based on (1) a shared name, (2) a shared interpretation of origin (myth), (3) shared memories of the past, (4) one or more shared elements of culture, (5) a link to the homeland (“one’s own land”), and (6) a feeling of commonality with the members of the ethnic group.

This article examines ethnic identity from a constructivist perspective, characteristic of qualitative research, analyzing its situational nature and variability. It assumes that the same person in the same situation may draw a boundary between local and ethnic identity or may dissociate from it and not even be interested in it. In other circumstances, the same person may behave differently. The ethnic identity approach is employed here to understand whether people living in Southeastern Lithuania at the beginning of the 21st century draw a boundary between their own land, their own geographical space and the rest of Lithuania, between people who are considered their own and those who are considered strangers.

The empirical data collected in the late 20th – early 21st century from 17 LLA points on the southeastern periphery of Lithuania shows that most of the people who identify themselves as local people (Bel. мясцовыя, тутэйшыя; Pol. miejscowi, tutejszi) consider themselves to be Polish. However, about 40% of the elderly and middle-generation respondents surveyed in Jašiūnai, Tabariškės, Šalčininkai, Eišiškės, Turgeliai, and Butrimonys openly admit that they cannot call themselves “full-fledged Poles” (Pol. pełnoprawny polak) because they have people of different nationalities in their family. Recalling their childhood, they talk about their grandparents who spoke Lithuanian to each other and did not even know Polish prayers. The first place where today’s elderly generation learnt “grammatical” Polish (Pol. gramatyczny Polski) was during religious ceremonies and masses in local churches, while in everyday life, whether on the street or with neighbors, everyone usually communicated in simple Belarusian.

Thus, some of the elderly respondents who identify themselves as Poles consider the Polish they once learned “poorly” and still use today to be a “mixed” language, i.e. half Belarusian and half Polish. In their view, proficiency in the official Polish language and its full use are the most important markers of Polishness. The current middle generation graduated from Russian schools during the Soviet era, where Polish was not yet taught. People remember that in their childhood, their parents spoke Lithuanian when communicating with their grandparents and older neighbors but prayed in Polish (Tuomienė 2023: 82–92). They no longer taught Lithuanian to their children, prioritizing Russian as the language used in public, while reserving Polish for church and family gatherings.

In the post-war period, the prestige of Russian and Polish continued to grow, becoming the promising languages that everyone would supposedly need in the future. Children picked them up easily and, according to the informants, “we understood everything early on, but there was no one to talk to (except teachers and priests). One language, Belarusian, was enough everywhere” (77-year-old woman, Eišiškės). Meanwhile, the Lithuanian dialects spoken along the Belarusian border gradually became a symbol of the past, progressively forgotten and, according to locals, no longer viable.

Most older people tend to emphasize the status of Polish as the only confessional language, stressing a long-standing tradition of praying exclusively in Polish in church and singing traditional Polish hymns at christenings, weddings, and funerals. Village singers can also sing in Belarusian, though they claim these songs were translated from Polish (Krupowies 2017: 721–743). According to a woman born in Krakūnai in 1950, local singers learned Lithuanian traditional songs only later. However, the oldest interviewee from the village of Kaniūkai claimed that in her youth, all the women in the village knew many Lithuanian traditional hymns and folk songs.

In the past, according to the older generation, Polish was rarely spoken in private settings, reserving it to “certain occasions” only: for praying in church and celebrating calendar and traditional festivals. In the village, Polish was regarded as “a language of higher culture and was not used in everyday life but rather on special occasions, especially religious holidays, when distant relatives from Poland would visit” (from the account of a woman born in 1944 in Daulėnai). Thus, in the surveyed points, 56 members of the older and middle generation, which is almost 70% of the respondents, declared that they cherish the Polish culture and traditions of their “family” or “neighbors”.

The analysis of the collected data revealed that narratives about historical events persist in people’s memory. Some of the region’s inhabitants remembered recent events firsthand, while others had learned about them from their relatives who had lived through periods such as the Polish occupation and World War II (cf. Marcinkevičius 2016b: 34–47; Ušinskiene 2016: 63–79; Buchaveckas 1992). The data revealed that the frequent redrawing of national borders led different population groups and different generations to develop different perceptions of their land and their country, their language, their religion, their traditions and customs, their laws, etc.

The frequent changes of government and the introduction of new rules were supposed to be a dividing factor among the population. However, the opposite trend was observed: the challenging conditions in Southeastern Lithuania fostered unity rather than division.

The collapse of states and the emergence of new ones, revolutions, and two world wars left the inhabitants of the surveyed Šalčininkai district with virtually no opportunities to express their ethnic, or national, civic, and political position. Memories from the older generation testify that people were forced to assume a socially passive role (cf. Tuomienė 2017: 788–826). The biographical histories of this generation revealed another interesting fact: the radical political, economic and social changes that took place in the Lithuanian border area did not strengthen the sense of belonging to a particular state, religion, language and culture, but rather led to its rejection (cf. Brubaker 1996: 411–437; Šutinienė 2015: 89–97; Vyšniauskas 2020b: 30–32). As a result, some inhabitants of these areas still identified themselves as Polish citizens, while others considered themselves Belarusian. This phenomenon, where people from the same locality associate with different countries, is still relevant today.

The data also revealed that the deliberate reluctance of the great-grandparents and grandparents of today’s middle generation to disclose their true, inherited identities has also made it much more difficult for the current generations to identify themselves. For example, some younger individuals, when asked, began to wonder who their grandparents, now speaking po prostu (in the Eišiškės area), really were. Therefore, most young people tend to distance themselves, opting for a neutral position.

In scholarly literature, the local inhabitants (Tuteishy) of Eastern and Southeastern Lithuania, who do not have a fully formed national identity (cf. Brubaker 2015: 3–32), are associated with localism (Ioffe 2003: 1241–1272; Weeks 2003: 211–224). On the other hand, the study shows that this self-identified Polishness is not always explicitly expressed. This may be because people who live in the Šalčininkai district and identify themselves as Poles have little or no connection to ethnic Polish culture (cf. Šliavaitė 2015: 27–51; Marcinkevičius 2016a: 22–34).

The people interviewed in the 17 LLA points primarily identified with their place of residence rather than with their inherited Polish culture, Polish language, and long-standing traditions passed down through generations. The study showed that most residents define their Polishness primarily through their place of residence and Catholic religion. Old, inherited Polish traditions are not well known in the region. Most often, people refer to retold stories from the past, in which the storytellers themselves were not directly involved (cf. Vyšniauskas 2020b: 29–47).

The analysis of conversations and interviews with villagers shows that localness (Bel. тутэйшасць, Pol. tutejszaść) generally meant a conscious unwillingness to acknowledge belonging to any specific ethnic group or nation. This can be seen as a nuance of a specific form of patriotism (cf. Snyder 2003), as an expression of opposition to both Poles and Russians, deliberate apoliticality, and cultural resistance. Some scholars associate localness with the frequent geographical renaming of the region, which started in the second half of the 18th century (cf. Pershái 2008: 86–88).

All interviewees spoke of past fears that any decision or choice they made could disrupt the traditional and peaceful way of life in the community. According to their elders, there used to be conflicts between Lithuanians and Poles in church over the language of the service. In other words, the residents of the periphery decided to “dissociate” primarily for self-preservation. For example, local Lithuanians, who had been bilingual since childhood and later switched to the Belarusian dialect, shared how they “became” Tuteishy:

(1) Čia gyvena savi, mūsų žmonės, visi kaimynai buvo lietuviai. <...> Dabar jau visokių yra. Prie lenkų likom be lietuviškų mišių. Pamenu, mano tėvas nėjo į lenkiškas mišias. Tai mama viena ėjo bažnyčion, a tėvas tik an kapų. Mokyklas lenkiškas padarė, paskui rusiškas <...>. Kaip aš augau, tai lietuviškai skaityti nemokėjom. Žmonės gudiškai mokėjo, bet nekalbėjo. Paskui kalbos persimainė, jau visi išmoko baltarusiškai. Žmonės liko tie patys. Tėvas lietuviškai ūtaryja, o sūnus jau lenkiškai. Anas paliokas jau. Bažnyčion nuveina, ten jau tik lenkiškai. Jauniems lenkiškai gražiau, tai anys greita išmoko. <...>. Visaip tuos žmones vadino. Tutašni, bo žyje tut.

‘Our people live here;our neighbors were all Lithuanians. <...> Now there are all kinds of people. Under the Poles, we were left without Lithuanian masses. I remember my father did not go to the Polish mass. My mother would go to church alone, and my father would only go to the cemetery. They made the schools Polish, then Russian <...>. When I was growing up, we could not read Lithuanian. People knew Belarusian, but they did not speak it. Then the languages switched, and everybody learned Belarusian. The people stayed the same. The father speaks Lithuanian, and the son speaks Polish. He is already a Pole. He goes to church, and there he speaks only Polish. The young ones find Polish nicer, so they learned it quickly. <...>. They called those people by all kinds of names. Tuteishy, because they live here’ (male, born in 1883 in Didžiosios Sėlos village, Šalčininkai district. Entry No. (2)31501650 is stored in the LLI Geolinguistic Centre’s Dialect Archive).

Thus, the analysis of the interviews shows that a large part of the population in the Šalčininkai district, due to the political and social circumstances, chose a neutral form of self-identification. This form of self-identification was also relevant in the 20th century and was ascribed to all ethnic groups of the border population (cf. Kurcz 2005; Pershái 2008: 94–96, 2010: 376–398; Nasuta 2005: 163–173).

The study also revealed a different approach towards Tuteishness, particularly as it has been advocated since the 19th century. It can be defined as another form of ‘national’ identity, expressed specifically through geography (cf. Śliwiński & Čekmonas 2017 [1997]: 143–191; Čekmonas 2017 [1994]a: 192–205; Čekman 2017 [1982]: 206–227).

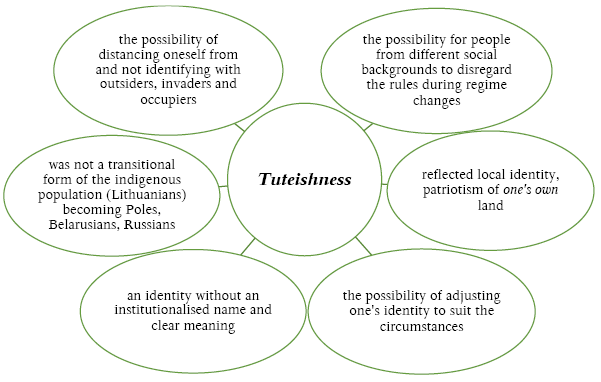

In conclusion, Tuteishness, as a form of cultural resistance, has helped the border population to resolve several important survival issues over time.

At the beginning of the 21st century, we can observe changes in the situation: issues of identity are becoming important and relevant for borderland residents. The changes here are twofold. The majority of the older and, to some extent, middle-aged population of the Šalčininkai district still deal with identity issues in the same way, relying on past stories (or myths) about the “Polishness” of their family, passed down from one generation to the next by their parents and grandparents: the “inheritance” of the Polish traditions and the Polish language. It is especially important to observe Polish Catholic rites. Speakers commented on cases where people’s decisions were influenced by changes in the political and social situation. It is worth noting that in today’s multilingual society, language is no longer the key factor in people’s identity decisions. It should be noted that this factor is still relevant to the younger generation.

The second direction of change is the ethnic and civic self-determination of the younger generation. Thus, the younger generation living or still studying in the Šalčininkai district, having grown up in independent Lithuania, already expresses a slightly different attitude towards Tuteishness as a local identity. It can be predicted that over time the number of people who consider themselves local will decrease in the district, while the number of those who prioritize civic identity will increase.

Surveys have shown that young people are no longer interested in drawing lines between locals and non-locals. Young people often leave their home region of Šalčininkai to study or work elsewhere, both in Lithuania and abroad. Undoubtedly, exposure to new environments encourages them to emphasize their civic identity. The data analyzed show that over time, there are important processes of identity shift taking place across the region, which are likely to gradually change the identity practices of the local population and lead to the rethinking of the dynamics of ethnic relations throughout Southeastern Lithuania.

The residents of the older generation explain the uniqueness of “their land” by the fact that the people living in the area, or their parents and grandparents lived in Poland between the wars and had Polish citizenship (some of them still possess documents proving it). People say that “there was Poland here, and Lithuania is another country, starting somewhere around Kaunas”. This is why there are many Poles living in the Šalčininkai area, while Lithuanians live near Kaunas and further, in Žemaitija. “Everything has stayed the same here since those times” (from the memoirs of an 83-year-old woman, Butrimonys). The perception of living in two different countries has been preserved and partly passed on to the younger generation, who were born when the Šalčininkai district was already part of Lithuania.

It should be noted that the accounts of the older generation are consistent with social memory theory, which states that significant events remain in social memory for approximately one century. This was also confirmed by a 61-year-old man who recounted his parents’ biography. He stressed the connection between historical events and changes in the collective consciousness of the population, cf.:

(2) <...> buvo sovietų valdžia, paskui lietuvių, iškart lenkai visą kraštą užėmė. Prasidėjo karas ir atėjo vokiečiai, po karo – sovietai. Dabar ir vėl čia Lietuva. Tai kokioj valstybėj gyvenom? Jeigu per aštuoniasdešimt metų čia buvo Lenkija, Lietuva, Sovietų Sąjunga ir Baltarusija, dabar – ir vėl Lietuva <...>. Per visą mano tėvų gyvenimą valdžia keitėsi penkis kartus. Ir nauja valdžia žmogaus vis klausia: kas tu toks esi? Žmonės suprato, kad geriausia sakyti, kad esi vietinis. Ir viskas. Jestem tutejszy.

‘<...> There was Soviet rule, then Lithuanian, then the Poles immediately took over the whole region. The war started, and the Germans came; then the Soviets after the war. Now it is Lithuania again. So, what country did we actually live in? If over the course of eighty years this place was part of Poland, Lithuania, the Soviet Union, Belarus, and now Lithuania again <...>. In my parents’ lifetime, the government changed five times. And each new government keeps asking: Who are you? People realized that the best answer was simply to say they were local. And that’s it. Jestem tutejszy (Pol. I am local)’ (male, born in 1962 in Kudlos village, Pabarė area, Šalčininkai district. Entry No. 680 01 R. L. is stored in the LLI Geolinguistic Centre’s Dialect Archive).

Thus, the policies pursued by various states towards the people of this region encouraged them to identify primarily with the place where their parents and grandparents had lived, rather than with a particular ethnic group. Over time, newcomers and local inhabitants, along with their respective cultures, blended together to form a distinct local culture: “Everybody here has mixed together and become the same, and that’s it. Dzūkija, Žemaitija, and Vilnius each have their own culture, while ours is more Polish and Belarusian” (from the account of a 77-year-old man, Šalčininkai). People distanced themselves from adjacent areas (even Dzūkija, the ethnographic region to which Šalčininkai district formally belongs), where a single culture and language dominate3.

As a result, there are hardly any contacts with other cities and towns in Lithuania, primarily due to the language barrier. It was much more convenient for the local population not to learn Lithuanian, but to visit places where they could communicate in Russian, Polish or po prostu, i.e. Vilnius and the adjacent areas of Belarus. Rural residents talk a lot about the “Polish times”, the estates, the szlachta, their clothing, food, customs, and language. However, nowadays, only individual people have cultural contacts with Poland and its cities (for work, education, shopping). There are Polish folk song and dance groups in Šalčininkai, but even their clothing is not local, but imported from Poland, often even from the Cracow region (Nowak 2005: 48, 196–211; Krupowies 1997: 118–126).

The inhabitants of the present-day Šalčininkai district do not perceive any cultural differences between themselves and the people living on the other side of the state border in Northwestern Belarus. The current inhabitants of the Šalčininkai district who moved to Lithuania from nearby Belarus during the post-war and Soviet periods, mainly to the Eišiškės municipality of this district, consider themselves to be Belarusians, but refer to themselves as Poles due to their Catholic, i.e. “Polish”, faith (Pol. wiara polska).

In public places, they predominantly speak local Slavic languages: Russian and Polish. In private settings, the older generation speaks po prostu, the middle generation speaks either po prostu or trasianka, while among the young people trasianka is the most common. Trasianka is a strongly Russian-influenced form of the local Belarusian language (Cychun 2000: 51–58). This variable phenomenon, characteristic of the whole Belarusian territory, involves the replacement of individual Belarusian words or phrases with Russian ones, resulting in a form of code switching. Most of the older population does not understand Lithuanian, but the level of proficiency in Lithuanian is increasing among the younger ones, as the younger generation to some extent learns standard Lithuanian in schools (Tuomienė 2022a: 184–206).

The majority of the older generation considers Belarus to be their “real homeland” and visits it more often than other places in Lithuania. Belarusian traditions, namely language, festivals, folk and pop songs, and dances, remain close to them. Some members of the middle generation consider themselves Russian-speaking Catholics, even though Polish identity is stated in their official documents. The older generation living close to the border with Belarus has a similar perception of their everyday language and identity. The difference is that they regard the Polish language and Polish traditions as the most important markers of Catholicism, cf.:

(3) Visi čia esame katalikai, taigi lenkai. Meldžiamės lenkiškai, einame išpažinties – taip pat lenkiškai. Litanija irgi lenkiška. Kitos kalbos mūsų bažnyčioje nebuvo. Nepamenu. Butrimonių lenkiškoje mokykloje baigiau tik keturias klases. Mokėmės katekizmo lenkiškai. Mama kalbėjo lietuviškai, bet meldėsi lenkiškai. Mūsų popiežius Jonas Paulius II taip pat buvo lenkas.

‘We are all Catholics here, and therefore we are Poles. We pray in Polish; we go to confession in Polish. The litany is also in Polish. There was no other language in our church. I do not remember any. I finished only four grades in the Polish school in Butrimonys. We learned the catechism in Polish. My mother spoke Lithuanian but prayed in Polish. Our Pope John Paul II was also Polish’ (female, born in 1937 in Pabarė village, Butrimonys area, Šalčininkai district. Entry No. 682 03 J. V. is stored in the LLI Geolinguistic Centre’s Dialect Archive).

Those who came from Belarus, such as Varanavas (Bel. Вoранава), Benekainys (Bel. Бенякoнi), Geranainys (Bel. Геранёны), Rodūnia (Bel. Рaдунь), Lyda (Bel. Лiда), and Vija (Bel. Іўе), etc., are concentrated primarily in the southeastern part of the Šalčininkai district, near the present-day border with Belarus. There are 11 LLA points in this area: Kaniūkai, Butrimonys, Eišiškės, Daugidonys, Šalčininkai, Miežionys, Dailidės, Maciučiai, Daulėnai, Tabariškės, and Kurmelionys. Meanwhile, the largest number of long-established residents, i.e. those born and living in the same place for generations in the Šalčininkai district, is found in the western and northwestern parts of the district, in places such as Rūdninkai, Gudeliai, Šalčininkėliai, Vėžionys, and Kuršiai.

It is like living in two countries. Interviewees from Eišiškės illustrate this point well. Four women (born in 1953, 1949, 1946, and 1939 in Belarus) and two men (born in 1975 and 1945 in Belarus) described their lives as жывëм напалoву ў Беларусі (“we live half in Belarus”). They communicate with their neighbors using па прoсту, па прoстэму, па меснаму, па тутэйшаму (po prostu). In the past, they regularly visited their relatives in Belarus or hosted them in Lithuania, but since the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, contacts with Belarus weakened significantly.

The surrounding area of the Šalčininkai district (except for the small Dieveniškės “appendix”) belongs to the Southern Aukštaitian dialect. However, as the survey showed, the younger and middle-aged inhabitants of Butrimonys, Eišiškės, Rūdninkai, Turgeliai, and Vėžionys no longer identify themselves with any dialect. The younger generation had no idea of which Lithuanian dialect might have been spoken in the area before the middle of the 20th century and stated that they had never heard their parents or grandparents speak to each other in any Lithuanian dialect.

Previous research indicates that regional identity in Southeastern Lithuania remains important to this day, but the content of this identity has changed: the emphasis is no longer on ethno-cultural distinctiveness but rather on self-identification with the Vilnius region in a broad sense and one’s specific place of residence (the region) in a narrower sense. For example, in surveys, middle-generation people who consider themselves Poles said that in their homeland, they are locals, Poles who speak in various ways and followers of the Polish traditions of the Vilnius region. They admitted that these traditions are old but are almost indistinguishable from “local Lithuanian” and “local Belarusian” traditions.

The relationship between nationality and language is not easy for the population to describe: a variety of responses are formulated, usually consisting of multiple components. It should be noted that individuals do not always draw a connection between nationality and language. For example, people of Polish nationality are perceived as understanding Polish and knowing how to observe all church rituals in Polish, yet they speak Russian in their everyday life (cf. Geben 2013: 217–234; Zielińska 2008: 165–176).

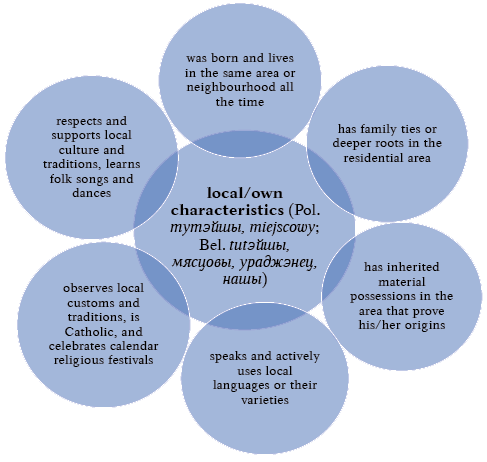

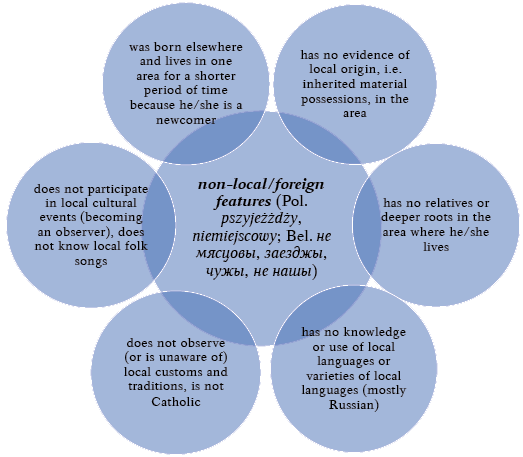

It is worth stressing once again that the concept of localness remains very important to the residents of the Šalčininkai district, who have developed a common perception of distinguishing between locals and non-locals. The residents who consider themselves Polish and who, as already mentioned, constitute the ethnic majority in the studied areas, use several terms to describe these concepts. For example, for local: Pol. tutejszy, miejscowy; Bel. тутэйшы, мясцовы, ураджэнец, нашы; and for non-local: Pol. pszyjeżżdży, niemiejscowy; Bel. нe мясцовы, заезджы, чужы, нe нашы. Thus, people living in the borderlands tend to categorize their neighbors and the inhabitants of the surrounding areas into several groups: local Poles, local Lithuanians, local Belarusians, or simply locals (cf. Korzeniewska 2013: 167–174; Geben 2014: 186–197).

For people who consider themselves locals in the Šalčininkai district, it is not only important that they were born in this district but also that their grandparents and parents were born and lived there for a long time. People willingly share their memories and stories, which, in a way, prove and confirm their local origins. Another defining characteristic of a local resident is the possession of tangible evidence of localness (Pol. miejscowość). These are usually houses and other property where the person lives or lived as a child, the graves of relatives, documents of origin, land, etc. For example, a local woman, who graduated from a Polish school, reflects on her children’s future in the house built by her grandfather, cf.:

(4) <...> w mojej rodzinie wszyscy są polakami <...> i ja jestem polką. Zapisane w moich dokumentach. Tu mieszka mój dziadek i rodzice. Nu, mówią po polsku. Dziadek zbudował ten dom. Może nasze dzieci też tu zamieszkają. Teraz chodzi do rosyjskiego „sadziku“, ale pójdą do polskiej szkoły. Nie wiem, czy mógłby uczyć się w szkole litewskiej. Byłoby to trudne, bo oni mówią po rosyjsku i po polsku <...>.

‘Everyone in my family is Polish. And I am Polish. It is written in my documents. My grandfather and parents live here. They speak Polish. My grandfather built this house. Maybe our children will live here too. Now they attend a Russian kindergarten, but they will go to a Polish school. I don’t know if they would be able to go to a Lithuanian school, because they only speak Russian and Polish’ (female, born in 1972 in Skivonys village, Daulėnai area, Šalčininkai district. Entry No. 668 02 D. S. is stored in the LLI Geolinguistic Centre’s Dialect Archive).

An indicator that distinguishes local people from non-local people is the ability of the population to communicate in all local (and regional) languages in everyday life. The oldest generation, having lived through World War II and the difficult post-war period of collectivization, has the strongest local identity. In almost 90 years, this generation was forced to learn and alternate between all four languages of the region. The most important reason for drawing the line between insiders and outsiders was self-protection during times of change and turmoil, especially when foreign (often temporary) settlers started to treat the locals with disrespect and lost their trust (Daukšas 2008: 53–68; Korzeniewska 2013: 149–179; Tuomienė & Meiliūnaitė 2022: 172–183).

According to the speakers, in the post-war period, strangers who had come to Southeastern Lithuania from other places were often appointed to managerial positions in workplaces. Disagreements and conflicts arose between locals and newcomers over the humiliation and even punishment of the locals. The newcomers did not know the languages spoken in the area, did not understand the customs of the people, did not respect the local culture, and when hostility or conflicts arose, non-local officials were quickly transferred elsewhere (Stravinskienė 2012: 125–138).

Informants testify that during the Soviet era, many locals suffered in one way or another; they were blamed for their language and nationality. Lithuanians, in particular, were disliked, so people chose strategies of maneuvering (or even survival) to protect themselves. One of these strategies was to emphasize localness. Speakers argued that no matter where they had come from, no matter how many years they had lived in a new area, they tried to fit in as quickly as possible by “getting the status of a local”. The recollections of a woman living in Kalesninkai describe the behavior of the newly arrived foreign officials towards the locals, especially Lithuanians, cf.:

(5) <...> вясковыя працавалі ў калгасе. Працавалі ў полі, на сенажаці. Усё рабілі сваімі рукамі. Прыходзіць брыгадзір і запісвае, хто тут сёння працуе. Быў такі калгасны брыгадзір Бялькоў, прыехаў з Расеі. Пісаў, як хацеў. Я хадзіў на працу кожны дзень, а ён незапісаў. Заплацілі мала, можа, рублёў пятнаццаць. Я пайшoў у калгасную кантору і кажу, я цэлы месяц працаваў, заплацілі толькі пятнаццаць рублёў. Mне злоснаадказалі: чаго крычыш, лiтвiн, не назначана табе <...>.

‘People in the village worked on the collective farm. We worked in the fields during the hay harvest. We did everything with our own hands. The foreman comes and writes down who is working here today. There was a foreman from the collective farm, named Bialkov, who came from Russia. He wrote whatever he wanted. I went to work every day, and he didn’t write it down. He paid me very little, maybe fifteen roubles. I went to the collective farm office and said, ‘I worked the whole month, and I was paid only fifteen roubles.’ They angrily replied, ‘Why are you shouting, Lithuanian, you are not entitled to it.’’ (female, born in 1952 in Rudnia village, Maciučiai area, Šalčininkai district. Entry No. 670 03 A. D. is stored in the LLI Geolinguistic Centre’s Dialect Archive).

This behavior by officials who came from elsewhere only reinforced the conditional division of the local population into locals and non-locals, i.e. strangers, newcomers. The newcomers were distrusted and, in the areas where they settled, they were considered strangers for life. Mutual assistance and support were expected only from the local people.

People of the older and middle generations emphasize living in their “own”, “our” or “local” land rather than in a particular state or even in a particular district, town, settlement, or village: “we are locals” (Bel. мы тутэйшыя, месныя), “everyone is one of us” (Bel. тут усе свае), “we were born here and live here” (Bel. тут радзiлiся i жывëм). They feel the linguistic and cultural boundaries between their “own” district and other areas (cf. Vyšniauskas 2020a: 89–91). Thus, the concept of localness or their land is understood much more broadly here than the current territory of the Lithuanian state. It also includes parts of Belarus, especially those areas with which people are connected by language and close kinship ties.

The data under study confirmed that important processes of identity change are taking place in the Šalčininkai district, which are likely to gradually alter the identity practices of the local population and prompt a rethinking and reassessment of the dynamics of ethnic relations.

Summarizing the main attributes that distinguish local/own and non-local/foreign people in the Šalčininkai district, it can be concluded that the older and middle generations consider two of them to be the most important attributes of localness: 1) long-term residence (a person can be born in the Vilnius region in the broad sense) and 2) the adherence to Catholic, and therefore Polish, traditions. The younger generation, however, is critical of this kind of classification.

Almost two-thirds of respondents who consider themselves Poles stated that they associate their future more with Lithuania than with neighboring countries. They are more oriented towards Vilnius, where they go or would go to study, work, and live. Some openly shared the reason for choosing the capital over cities like Kaunas or Alytus. According to them, Vilnius is a multinational city, so it is easier to communicate in Russian, Polish or Belarusian if you do not speak, or have a poor command of, the official Lithuanian language.

Almost half of the younger generation identifies the language spoken in the family as an important or even the main criterion of nationality, which unites the family. For them, language is natural, inherited like nationality. Therefore, they do not consider it necessary to discuss any choice or change of nationality. A small number of younger speakers expressed a different view. They argued that deciding which nationality to belong to is a matter of adult decision, especially in cases where parents or grandparents have different nationalities. Young people emphasize education and a person’s own interest in nationality and ethnicity (cf. Masaitis 2007).

It should be noted that not all people of the younger generation living in villages, small settlements or towns are concerned with issues of language choice and use, nationality, and ethnicity. It has been observed that the younger generation is quite critical of local identity and the distinction between local and non-local, own and foreign. Although not all, younger people are already showing a willingness to distance themselves from such an “outdated” model of identification, but they are not yet offering their own. Their distancing, although still tentative, reveals the emphasis of the younger generation on civic identity, which is often understood as a substitute for local identity. For example, a woman living in Šalčininkai, when asked about her attitude towards ethnic or national identity, said:

(6) <...> mano tautybė turbūt yra internacionalinė. Namuose kalbam lenkiškai, bet ne visada. Kai iš toliau susirenka giminės, tai rusiškai kalbam. Ne visi moka lenkiškai <...>. Mama pasakojo, kad vienas senelis mokėjo lietuviškai. Kitas senelis tik baltarusiškai. Bobutė buvo lenkė ir mama lenkė, kalba tik lenkiškai. Tėtis ir baltarusiškai, ir rusiškai kalba. Dar vaikas buvo, kai čia atvažiavo iš Baltarusijos <...>. Baigiau rusišką mokyklą. Buvo lietuvių kalbos pamokų, bet mažai. Kai išėjau dirbti, tada išmokau lietuviškai. Gyvenu Lietuvoje, tai reikia mokėti lietuviškai. Atvažiuoju čia, tai kalbam tik lenkiškai, rusiškai. Mūsų šeimos tradicija tokia <…>.

‘<...> My nationality is probably international. We speak Polish at home, but not always. When relatives from further away gather, we speak Russian. Not everyone speaks Polish <...>. My mother told me that one grandfather spoke Lithuanian. The other grandfather only spoke Belarusian. My grandmother was Polish, and my mother was Polish; they spoke only Polish. My dad spoke both Belarusian and Russian. He was still a child when he came here from Belarus <...>. I graduated from a Russian school. There were Lithuanian lessons, but not many. When I started working, that’s when I learned Lithuanian. I live in Lithuania, so I have to know Lithuanian. When I come back here, I only speak Polish and Russian. Our family tradition is like this <...>’ (female, born in 1998 in Šalčininkai. Entry No. 666 02 A. V. is stored in the LLI Geolinguistic Centre’s Dialect Archive).

A sociolinguistic survey of the residents of the LLA points in Southeastern Lithuania showed that the autobiographical, everyday stories and myths of the past told here are mainly oriented towards their own, local inhabitants: the Poles, the Lithuanians, the Belarusians, and the Russians. These forms of memory clearly show the changes in the self-awareness, self-perception, and worldview of the people living on the border. The memories of the older generation reveal the multicultural nature of the present-day Šalčininkai region. There is a desire to pass on the experience in oral form to future generations.

In the interviews with intergenerational residents, there were many similar responses, even though the people did not know each other and lived on different sides of the district. The interviews revealed many elements that unite the borderland residents. For example, the choice of the language of communication is a very important measure of togetherness and inclusiveness, indicating tolerance (Šliavaitė 2015: 37–39). The experience of multilingualism is seen as a natural phenomenon and as an advantage by both urban and rural people. Language shift in live conversations and written experience in the social space are part of the communication process of the people from the Šalčininkai region. When communicating, people naturally switch from one language to another or creatively incorporate phrases, figurative expressions, similes, and quotes in other languages. Therefore, code-switching occurred in almost all of the analyzed and overheard conversations of the borderland residents (cf. Tuomienė 2022b: 238–265).

The data confirmed that important processes of identification change are taking place in the Šalčininkai area, which are likely to gradually transform the identity practices of the local population and lead to a fresh re-thinking and re-evaluation of the dynamics of ethnic relations.

The foundation of the official dominant Polish identity of the inhabitants in Southeastern Lithuania has, for the past few centuries, been grounded not in the language, but in the ideology of power. Foreign rule in the territory of the present-day Šalčininkai district of the Republic of Lithuania, where this study was conducted, was established after the Third Partition of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1795, when the Russian Empire annexed these lands of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. With a brief interruption between 1918 and 1920, this rule lasted until 1990, and between the periods of Russian rule, the region was also subjected to Polish occupation from 1920 to 1939.

As a result, the inhabitants of Southeastern Lithuania did not have the opportunity to freely pass on the historical narrative of their origins from one generation to the next, as it was constantly politically adjusted to suit the interests of the government, reinforced by the argument of confessional affiliation: if you are Catholic, you are Polish. In this context, the local identity of the Belarusian-speaking population was formed as a counter to the process of denationalization. It is inherently resistant.

In the most recent study carried out in 2012–2013 in the Šalčininkai district, empirical data collected from 17 LLA points showed that from the middle of the 20th century to the second decade of the 21st century, the concept of identity of the local population was steadily changing, albeit at a relatively slow and slight pace. Although the latest data do not yet reflect a complete process of identity change, it is predictable that regional/local identity is gradually eroding while other forms of identification, in particular ethnic (more typical of the middle generation) and civic (more typical of the younger generation) identity, are strengthening.

The results of the study allow us to distinguish the following three types of identity among the region’s residents:

(a) due to the historical changes that took place in the past in this territory of the Vilnius region, there is a certain resistance and/or unwillingness to belong to any (including hereditary) ethnic group;

(b) the desire of older and middle-aged people to belong to a particular ethnic group by inheritance, to speak its language, observe its customs, religious and cultural traditions, and perceive their distinctiveness;

(c) a trend, especially among the younger generation, to distance themselves from, or even reject, local identity, with a priority given to civic identity, which is expressed by the need to learn and use the official language and to comply with the laws of the current state.

The statements made by identity theorists (Barth 1969; Branks 2005; Wimmer 2008) about the close relationship between social memory and identity, with collective memory in the form of a narrative being regarded as a key factor in the formation of human identity, are supported by the results of the research on the identity of the borderland inhabitants of Southeastern Lithuania, carried out at the beginning of the 21st century. It was found that only those who speak the same language (or the same languages, as in the case of the study described here) transmit the same narrative, remember and pass on the same myths, symbols, and stories, and practice the same religion. As a result, they consider themselves locals, i.e. as part of their community.

The collapse of states and their replacement by new ones, revolutions, and two world wars left virtually no opportunity for the inhabitants of the study area of Šalčininkai to express their ethnic or national, civic, and political position. The memories of the older generation testify to the fact that people were forced to assume a socially passive role.

The biographical histories of this generation show that the radical political, economic and social changes did not reinforce the sense of belonging to a particular state, religion, language and culture, but rather led to their rejection. As a result, some of the inhabitants of these areas still considered themselves Polish citizens at the time of this study, while others identified as Belarusians. This identification of local people in the same area with different countries is still relevant today.

The analysis of conversations and interviews with rural residents shows that the region’s inhabitants are characterized by Tuteishness, i.e. a form of national identity based on ties to a particular geographical location, whose inhabitants are linked in some way by ethnolinguistic, historical, socio-cultural, and political circumstances.

Tuteishness is the conscious reluctance of the population to acknowledge its membership in any ethnic group or nation, which can be seen as a nuance of a specific form of patriotism, as an expression of opposition to both Poles and Russians, a deliberate apolitical stance, and cultural resistance. Over time, Tuteishness helped the inhabitants of the study areas to resolve several important survival issues. However, it was not a transitional form of the population (autochthonous Lithuanians) becoming Poles, Belarusians or Russians, because it presents an opportunity:

(a) to designate an identity without an officially approved name and a clearly perceived meaning;

(b) not to identify and even distance oneself from the occupiers;

(c) not to comply with the rules imposed on different ethnic groups by changing regimes;

(d) the possibility of “adjusting” one’s identity according to the circumstances.

The people of the older and middle generations emphasize life in their “own”, “our” or “local” land, rather than in a particular country or district: мы тутэйшыя, месныя (Eng. we are local); тут усе свае (Eng. everyone is one of us), тут радзiлiся i жывëм (Eng. we were born here and we live here). They feel the linguistic and cultural boundaries between “their own” region and other areas. Their concept of their own land extends far beyond the current territory of the Lithuanian state, encompassing parts of Northwestern Belarus, with which they share a common language and close kinship ties.

Data analysis shows that local and non-local populations exhibit completely different characteristics. A local is someone who was born and has lived in the same area for their whole life or at least a significant part of it. They have relatives residing in the vicinity; their origin is evidenced by inherited material possessions; they speak and actively use three to four local languages; they are Catholic, adhere to local traditions and customs, and exhibit social behaviors aligned with the local culture and traditions. A non-local, by contrast, was born elsewhere and has only recently settled in the borderland area; they have no relatives or deeper family roots and no inherited material possessions as evidence of descent; they do not speak the local languages (often speaking Russian instead) and do not observe (or are unfamiliar with) local customs and traditions (despite being Catholic). As a result, they remain passive observers in the local cultural events.

The people of the younger generation, who have no memory of the Soviet era, seek to distance themselves from the emphasis on localism and attachment to their own land, although they do not yet propose their own identification model. Their distancing reveals the younger generation’s focus on civic (and to some extent ethnic) identity, which is often understood as a substitute for local identity.

The locals, or Tuteishy, are generally bilingual, and in some places multilingual. In informal settings, the Belarusian dialect po prostu has traditionally dominated in their lives, while in formal settings, the local variant of Polish and Russian continues to compete. The middle generation learned the standard Lithuanian language in schools or workplaces. On the other hand, since the choice of language in this region depends on the degree of dominance of one ethnic group or another, residents, even those who do not speak Polish, often recognize it as their nominal mother tongue.

The study revealed that one of the key innovations of the early 21st century is the emergence of a positive attitude towards the official Lithuanian language in the towns and larger settlements of Lithuania’s southeastern borderlands. It should be noted that the positive attitude towards Polish as a public language has not been lost, and its use is stimulated by its confessional function.

Antinienė, D. 2002. Asmens tautinio tapatumo tapsmas. Sociopsichologinės šio proceso interpretacijos. Sociologija. Mintis ir veiksmas 2, 100–107.

Banks, M. 2005. Ethnicity: Anthropological Constructions. London: Taylor & Francis e-Library.

Barth, F. 1969. Ethnic Groups and Boundaries: The Social Organization of Culture Difference. Bergen, Oslo: Universitets forlaget, London: George Allen & Unwin.

Bauman, G., A. Gingrich 2004. Grammars of Identity/Alterity. A Structural Approach. Oxford: Berghahn Books.

Brubaker, R. 1996. Nationalizing state in the old “New Europe” and the new. Ethnic and Racial Studies 19(2), 411–437.

Brubaker, R. 2004. Ethnicity Without Groups. Harvard: Harvard University Press.

Brubaker, R. 2015. Linguistic and religious pluralism: Between difference and inequality. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41(1), 3–32.

Buchaveckas, S. 1992. Šalčios žemė. Vilnius: Mintis.

Cychun, H. 2000. Krealizavany pradukt: Trasianka jak pradmet lingvistyčnaha dasledavannia. Arche-Skaryna Nr. 6, 51–58.

Czekmonas, W. 2017 [1991]. Nad etniczną i językową mapą Polaków litewskich – o teraźniejszości i przyszłości. Valerijus Čekmonas: kalbų kontaktai ir sociolingvistika. L. Kalėdienė (ed.). Vilnius: Lietuvių kalbos institutas, 115–127.

Čekman, V. N. 2017 [1982]. K sociolingvističeskoj charakteristike pol’skich govorov belorusko-litovskogo pograničja. Valerijus Čekmonas: kalbų kontaktai ir sociolingvistika. L. Kalėdienė (ed.). Vilnius: Lietuvių kalbos institutas, 206–227.

Čekmonas, V. 2017 [1994]a. K probleme pol’skogo nacional’nogo samosoznanija na litovsko-slovianskom pograničje. Valerijus Čekmonas: kalbų kontaktai ir sociolingvistika. L. Kalėdienė (ed.). Vilnius: Lietuvių kalbos institutas, 192–205.

Čekmonas, V. 2017 [1995]b. Dar sykį apie rankraščių likimą, arba įvadinio straipsnio pratarmė. Valerijus Čekmonas: kalbų kontaktai ir sociolingvistika. L. Kalėdienė (ed.). Vilnius: Lietuvių kalbos institutas, 61–107.

Čekmonas, V., L. Grumadienė 1993. Kalbų paplitimas rytų Lietuvoje. Lietuvos rytai. K. Garšva, L. Grumadienė (eds.). Vilnius: Valstybinis leidybos centras, 132–136.

Čekmonas, V., L. Grumadienė 1997. Lietuvių kalbos tarmių ir jų sąveikos tyrimo programa. Sociolingvistika. Vilnius: Lietuvių kalbos institutas.

Daukšas, D. 2008. Pase įrašytoji tapatybė: Lietuvos lenkų etninio / nacionalinio tapatumo trajektorijos. Lietuvos etnologija: socialinės antropologijos ir etnologijos studijos 8(17), 57–72. https://etalpykla.lituanistika.lt/fedora/objects/LT-LDB-0001:J.04~2008~1367163292500/datastreams/DS.002.0.01.ARTIC/content/

Daukšas, D. 2012. Lietuvos lenkai: etninio ir pilietinio identiteto konstravimas ribinėse zonose. Lietuvos etnologija: socialines antropologijos ir etnologijos studijos 21, 167–193.

Eriksen, T. H. 2002. Ethnicity and Nationalism: Anthropological Perspectives. London: Pluto Press.

Garšva K., L. Grumadienė (ed.). 1993. Lietuvos rytai. Vilnius: Valstybinis leidybos centras.

Geben, K. 2013. Lietuvos lenkai ir lenkų kalba Lietuvoje. Miestai ir kalbos 2. Sociolingvistinis Lietuvos žemėlapis: kolektyvinė monografija. M. Ramonienė (ed.). Vilnius: Vilniaus universitetas, 217–234.

Geben, K. 2014. Trudności młodzieży polskiej na Litwie w uczeniu się języka ogólnopolskiego. Kalba ir kontekstai. Mokslo darbai 2014 m. VI. 1 tomas 2 dalis. Vilnius: Lietuvos edukologijos universiteto leidykla, 186–197.

Hutchinson, J., D. A. Smith 1996. Ethnicity. Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press.

Ioffe, G. 2003. Understanding Belarus: Belarusian identity. Europa-Asia Studies Vol. 55, No. 8, December, 1241–1272.

Korzeniewska, K. 2013. „Vietinis“ (tutejszy), lenkas, katalikas: Pietryčių Lietuvos gyventojų religinė-etninė tapatybė (tyrimas Dieveniškėse, Kernavėje ir Turgeliuose). Etniškumo studijos 2, 149–179. http://ces.lt/en/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/2013_2-Etniskumo-studijos.149-179.pdf

Krupowies, M. 1997. Polska pieśń na Litwie na tle sytuacji socjolingwistycznej i etnokulturowej. Slavistica Vilnensis 46 (2), 118–126.

Krupowies, M. 2017. Repertuar wokalny a identyfikacja etniczna i kulturowa ludności polskojęzycznych terenów Litwy. Valerijus Čekmonas: kalbų kontaktai ir sociolingvistika, L. Kalėdienė (ed.). Vilnius: Lietuvių kalbos institutas, 721–743.

Kurcz, Z. 2005. Mniejszość polska na Wileńszczyźnie: studium socjologiczne. Wrocław: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego.

Leonavičius, V. 1999. Bendruomenės savimonės raida ir tautos sąvokos reikšmės. Sociologija. Mintis ir veiksmas 3(5), 33–44.

Marcinkevičius, A. 2016a. Pietryčių Lietuvos regiono tyrimų apžvalga. Etniškumas ir identitetai Pietryčių Lietuvoje: raiška, veiksniai ir kontekstai. Kolektyvinė monografija. A. Marcinkevičius, K. Šliavaitė, M. Frėjutė-Rakauskienė (eds.). Vilnius: Lietuvos socialinių tyrimų centras, 22–34.

Marcinkevičius, A. 2016b. Istorinių, demografinių ir politinių procesų Pietryčių Lietuvoje XIX a. pab. – XX a. apybraiža. Etniškumas ir identitetai Pietryčių Lietuvoje: raiška, veiksniai ir kontekstai. Kolektyvinė monografija. A. Marcinkevičius, K. Šliavaitė, M. Frėjutė-Rakauskienė (eds.). Vilnius: Lietuvos socialinių tyrimų centras, 34–47.

Masaitis, A. 2007. Marijampolio vaikai. Vilnius: Homo liber.

Mikulėnienė, D., V. Meiliūnaitė (eds.) 2014. XXI a. pradžios lietuvių tarmės: geolingvistinis ir sociolingvistinis tyrimas (žemėlapiai ir jų komentarai), Vilnius: Briedis.

Nasuta, A. 2005. Charyzma tutejšasci. Druvis 1, 163–173.

Naumenko, L. I. 2012. Belorusskaja identičnost̛. Soderžanije. Dinamika. Social’no-demografičeskaja specifika. Minsk: Navuka.

Neumann, I. B. 1999. Uses of the Other: “The East” in European Identity Formation. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Nowak, T. M. 2005. Tradycje muzyczne społeczności polskiej na Wileńszczyźnie. Opinie i zachowania. Warszawa: Towarzystwo Naukowe Warszawskie.

Pershái, A. 2008. Localness and Mobility in Belarusian Nationalism: The Tactic of Tuteishść. Nationalities Papers 36, No. 1, 85–103.

Pershái, А. 2010. Minor Nation: The Alternative Modes of Belarusian Nationalism. East European Politics and Society 24, 376–398.

Savukynas, V. 2003. Etnokonfesiniai santykiai Pietryčių Lietuvoje istorinės antropologijos aspektu. Kultūrologija, 87–91.

Śliwiński, M., V. Čekmonas 2017 [1997]. Świadomość narodowa mieszkańców Litwy i Białorusi. Valerijus Čekmonas: kalbų kontaktai ir sociolingvistika. L. Kalėdienė (ed.). Vilnius: Lietuvių kalbos institutas, 143–191.

Smith, D. A. 1986. The Ethnic Origins of Nations. Oxford: Blackwell.

Snyder, T. 2003. The Reconstruction of Nations: Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, 1569–1999. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Stravinskienė, V. 2012. Rytų ir Pietryčių Lietuvos gyventojų lenkų ir rusų santykiai: 1944–1964 metai. Lietuvos istorijos metraštis 2, 125–138.

Šliavaitė, K. 2015. Kalba, tapatumas ir tarpetniniai santykiai Pietryčių Lietuvoje: daugiakultūriškumo patirtys ir iššūkiai kasdieniuose kontekstuose. Lietuvos etnologija. Socialinės antropologijos ir etnologijos studijos 15(24), 27–52. https://www.istorija.lt/data/public/uploads/2020/09/lietuvos-etnologija-15-24-4-kristina-c5a0liavaitc497-kalba-tapatumas-p.-27-52.pdf

Šutinienė, I. 2015. Tautos istorijos pasakojimo raiška daugiakultūrėje aplinkoje: Pietryčių Lietuvos lenkų etninės grupės atvejis. Sociologija. Mintis ir veiksmas 2(37), 85–105. https://www.zurnalai.vu.lt/sociologija-mintis-ir-veiksmas/article/view/9866/7689

Tuomienė, N. 2017. Ramaškonių lietuvių sala Baltarusijoje – pereinamoji kalbų zona. Valerijus Čekmonas: kalbų kontaktai ir sociolingvistika. L. Kalėdienė (ed.). Vilnius: Lietuvių kalbos institutas, 788–825.

Tuomienė, N. 2022a. Kalbų funkcionavimas Šalčininkų apylinkėse: kaita ir konkurencija. Lietuviškumo (savi)raiška Šalčininkų rajone: aplinkybės ir galimybės. Vilnius: Lietuvių kalbos institutas, 184–206. http://lki.lt/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Lietuviskumo-saviraiska-Salcininku-rajone-1.pdf

Tuomienė, N. 2022b. Kodų kaitos funkcijos Pietryčių Lietuvos diskurse. Linguistica Lettica 30, 238–265. https://lavi.lu.lv/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Linguistica_Lettica_30.pdf

Tuomienė, N., V. Meiliūnaitė 2022. Šalčininkų rajono gyventojų tapatybė. Lietuviškumo (savi)raiška Šalčininkų rajone: aplinkybės ir galimybės, Vilnius: Lietuvių kalbos institutas, 172–183. http://lki.lt/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Lietuviskumo-saviraiska-Salcininku-rajone-1.pdf