A Pilot Study of Four Phonetic Changes in General British

Lina

Bikelienė

Vilnius University,

Universiteto 5, Vilnius,

Lithuania

Email: lina.bikeliene@flf.vu.lt

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4696-912X

Research Interests: phonetics, pronunciation teaching, learner

language.

Laura Černelytė

Vilnius

University,

Universiteto 5, Vilnius, Lithuania

Email: laura.cernelyte@uki.stud.vu.lt

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2604-6421

Research Interests: articulatory phonetics;

pronunciation teaching; language standardisation; language

variation.

Abstract. The pilot study reports on the prevalence of four phonetic changes (yod coalescence, yod dropping, /ʒ/ versus /ʤ/ in loan words, and GOAT allophony) in General British. The study consists of two stages to address the question from different perspectives: native speakers’ preferences and documentation of the changes in current pronouncing dictionaries.Sixty words likely to undergo one of the changes are chosen for the analysis. The survey is based on the framework by Wells (1998). Though the descriptive study resultsreveal a high degree of the respondents’ preference for ‘modern’ pronunciation, it varies across categories. The comparative analysis of the manifestation of the changes in the Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (2008), the Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (2011), and the Current British English Searchable Transcriptions (N/A) indicate their gradual way into the ‘standard’ language.

Key words: phonetic changes, pronunciation dictionaries, allophony, yod coalescence, yod dropping, loan words, General British

JEL Code: G35

Copyright © 2020

Lina Bikelienė, Laura Černelytė.Published by Vilnius University Press. This is

an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons

Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and

reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are

credited.

Pateikta / Submitted on

15.12.20

Introduction

In the 20th century, the Kachruvian concentric circles (Kachru 1998) helped to sort English speakers into speakers of English as a first (the Inner Circle), as an institutionalised (the Outer Circle), and as a foreign language (the Expanding Circle). Kachru (1985) considered the Inner Circle varieties to be ‘norm-providing’ or ‘norm makers’. The other two were seen as‘norm-developing’ and ‘norm-dependent’ respectively, collectively “treated as the ‘norm breakers’“(Kachru 1985, p.7). Globalisation has challenged this classification. The rise of global English and world Englishes have redefined the accepted norms.The Received Pronunciation (RP) acrolect, once considered a norm of British English variety (one of the main Inner Circle’s varieties), used to be the only accent employed by the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). Nowadays, RP has lost its position and should “be referred to in the past tense” (Lindsey 2019, p.5).

Contemporary society’s overt postulates of the importance of diversity have had an impact on the domain of language use.On the one hand, prominent society figures are heard to employ a number of accents. On the other hand, non-native speaker accents have been reported to negatively affect their credibility, signalling their out-group membership (Lev-Ari &Keysar 2010). Despite the acceptance of diversity, even a native speakers’ accent can hinder communication. As Trudgill notes “RP-speakers may be perceived, as soon as they start speaking, as haughty and unfriendly by non-RPspeakers unless and until they are able to demonstrate the contrary. They are, as it were, guilty until proved innocent”(2000, p.195).To have a choice to blend using the standard accent, or to be “guilty until proved innocent” (ibid.), it is crucial to define what ‘standard’ is.With respect to pronunciation, Locker and Strässler (2008) relate standard to Daniel Jones and his first pronunciation dictionary, published in 1917. The present article follows this point of view examining its 18th edition (Cambridge English Pronouncing dictionary (CEP),2011) alongside the Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (LPD) (2008) and the Current British English Searchable Transcriptions (CUBE) (N/A).The dictionariesprovide words in “the standard accents chosen for British and American English” (CEP2006, p.vi). The study, however, is limited to the former as a reference point since this variety is more often used as a model than American English (Cruttenden 2014), and “it is important to base one’s description of variation in the features of pronunciation on one variety of English” (Low2015, p.15).From a plethora of terms to describe standard British English, the article follows Cruttenden (2014) and Carley et al. (2018) in labelling it General British.

Phonetic changes have been addressed in linguistic literature to a different extent (cf. Wells 2000, Sauer 2002, Hannisdal 2006, Levey 2014, Mott 2014). Since it is not a finite phenomenon, constant monitoring is necessaryto observe and document the current processes tomodify dictionaries and teaching materials accordingly and provide a more representative view on GB.

The present paper aims at analysing how widespread four phonetic changes, namely, yod dropping, yod coalescence, /ʒ/ versus /ʤ/in loan words, and GOAT allophony, are in GB. For the pilot study,data is collected from a survey of native speakers’ preferences and threepronunciation dictionaries. The formeris used for an attempt to identify the degree of acceptance of the changes by native speakers, while the latter helps to determine some tendencies concerning manifestation of the changes under consideration in the specialised pronunciation dictionaries.

Standard and innovations

The standard of British English

Standard British English is one of the most extensively studied varieties of English. There is an ongoing debate, however, on what should be considered a standard, its importance for language studies, and the naming of it. One of the first attempts to conceptualise standard British English pronunciation is often assigned to Alexander Ellis, who introduced the term Received Pronunciation and defined it as “the educated pronunciation of the metropolis, of the court, the pulpit and the bar” (1869, p. 23). The term was modified by Daniel Jones as characteristic speech “of Southern English people who have been educated at the public schools” (1917, p. 15).Received Pronunciation was seen as prestigious, became the favoured accent of BBC (Moreno Falcón 2017, p. 4) and was alternatively named as BBC English. In the second half of the 21st century, RP “became an object of mockery or resentment” (Lindsey 2019, p. 3). Stigmatisation of RP led speakers to include features of regional accents to disguise their “prestige” (Trudgill 2000).

A number of linguists made attempts to codify the new standard pronunciation under the names of General British (Cruttenden 2014), Non-regional pronunciation (Collins and Mees 2013), Standard Southern British pronunciation (Lindsey 2019), Standard Southern British English (Harrington et al. 2011), EnglishEnglish (Trudgill & Hannah 2008), Modern RP (Trudgill 2001),RP (as opposed to traditional RP (Upton 2004), etc. The term RP for the standard accent of British English, however, resurfaces even in current publications (cf. Kortmann 2020). To refer to “a twenty-first-century model of educated British English” (Carley et al. 2018, Preface), the present paper adopts the term General British.

Innovations in General British

Recently General British has been undergoing rapid changes. While some features of current pronunciation can be “short-lived and not worth adopting” (Sauer 2002, p. 222), others are important for learners “to avoid being judged old-fashioned or affected” (Upton 2004, p. 2019).

Lindsey (2019), in his concise description of contemporary standard British pronunciation model, presented the changes in vowel and consonantal systems, stress patterns, connected speech, and intonation. Changes can be classified based on the types of variability. Sauer’s (2002) classification of phonemic-systemic, phonetic-realisational, and lexical-incidental types was supplemented with connected speech variability by Hannisdal (2006) (cf. Wells 1982). The grouping of changes into ‘almost complete’, ‘well established’, and ‘recent trends’indicates various stages of their acceptance into the system of standard pronunciation, and can be rather subjective. For example, the lowering of TRAP vowel, attributed to ‘well established’ by Cruttenden (2014), was assigned to the ‘almost complete’ group by Hannisdal (2006).

The presentarticle focuses on four phonetic changes (yod coalescence, yod dropping, non-anglicised variants with /ʒ/ within loan words, and GOAT allophony)at different developmental stages as classified by Cruttenden 2014.

Yod coalescence (yod palatalisation) and yod dropping (yod elision), changes, regarded as ‘almost complete’, representpartial or total cluster reduction, i.e.omission of the consonant from the cluster. As Glain (2012, p. 4) noted, “elision and palatalisation in /tju:, dju:, sju:, zju:/ sequences are contemporary manifestations of a long tendency that has historically involved the disappearance of /j/ from /C[1]ju:(ʊ)/ sequences.” These processes have affected such words as ‘durable’, ‘attitude’, ‘consume’, ‘resume’, etc. The traditional pronunciations /djʊərəbəl, ætɪtjuːd, kənsjuːm, rizjuːm/ are often replaced by either /dʒʊərəbəl, ætɪtʃuːd, kənʃuːm, riʒuːm/ or /dʊrəbəl, ætɪtuːd, kənsuːm, rizuːm/. Some linguists (e.g., Hannisdal 2006, Lindsey 2019), however, adopt a narrower point of view, where yod coalescence is attributed to the assimilation of /j/ with a preceding alveolar plosive.

Coalescence can be found in all three positions of the word: front, mid, and final, to “provide a less formal alternative to the more ‘careful’ forms” (Upton 2004, p. 229), as well as across word boundaries. Yod coalescence, having started in weak syllables (Lindsey 2019), has spread to stressed positions (Levey 2014). Yod dropping, illustrative of total cluster reduction, is characteristic word-initially (Upton 2004). Both changes can be seen as a step towards the universally preferred single-consonant onsets (cf. Hannisdal 2006, Wells 1982).

Loan words, or imports, with /ʒ/, which traditionally were anglicised, fall into the category of ‘well established’ changes. /ʒ/ is known to have limited distribution (cf. Roach 2009, Cruttenden 2014). In the English language, its characteristic position is word-medial. Word-initially and word-finally it is usually limited to recent imports from French or Italian. The change, thus, widens the distribution of /ʒ/word-internally toall the positions. For example, ‘gigolo’ becomes /ʒɪɡələʊ/ instead of /dʒɪɡələʊ/, some speakers show a preference for /lænʒəri/ instead of /lændʒəri/. In the case of final position, the word ‘prestige’ tends to be pronounced as /prestiːʒ/, whereas formerly, the anglicised version with ‘/dʒ/’ in the final position was the preferred alternative.

One of the ‘recent trends’ affects GOAT diphthong. Traditionally it was pronounced with a closing backing diphthong /əʊ/ with a starting point of a mid-central vowel (Roach 2009, Upton 2004). Nowadays the words with a dark /l/ in a syllable-final position tend to experience GOAT backing (Lindsey 2019), i.e., the starting point being closer to the LOT vowel. While Collins and Mees (2013) attributed this change to the pronunciation of London-born or those under the influence of London speech, Lindsey (2019) included it among the featuresof Standard British pronunciation that have changed. The new variant being common in the media is reported in Hannisdal (2006).

Most of the discussed changes have a low functional load, i.e., the meaning is not affected, but, as Mott (2014, p. 375) states “it would be wise for teachers to produce pronunciation models for their students” giving them a choice to adopt or reject the models andhelping them not to sound old-fashioned due to their ignorance.

Methodologyand data

The pilot study was conducted in two stages: analysis of survey findings and analysis of manifestation of phonetic changes in pronouncing dictionaries.60 words (Table-1) likely to have manifestation of the four phonetic changes under consideration, namely, yod coalescence and yod dropping (under the heading of /Cju:(ʊ)/, where C stands for an alveolar fricative of plosive consonant ), /ʤ/ vs. /ʒ/ in loan words, and GOAT allophony, were chosen for the analysis. The variants with /dj/, /tj/, /zj/, /sj/ in yod coalescence and yod dropping group, anglicised variants of loan words, and /əʊ/ before dark /l/ were referred to as traditional, while the variants with /ʤ/, /ʧ/, /ʒ/, /ʃ/; non-anglicised loan words with /ʒ/, and [ɒʊ] before dark /l/were considered to be‘modern’.

Table-1: The words chosen for the analysis.

Words with |

Loan words |

Words with before dark /l/ |

Assume, attitude, constitution, consume, costume, destitute, due, duel, duke, dune, duty, education, induce, module, presume, resume, situation, tube, Tuesday,tune. |

Adagio, barrage, beige, camouflage, doge, espionage,gauge, gelatine, genre, gigolo, gigue, jabot, jargon, journal, lingerie, management, massage, prestige, regime, rouge. |

Bold, bolt, bowl, coal, cold, fold, goal, gold, hole, holy, mould, moult, old, role, roll, shoal, sole, soul, told, wholly. |

Theonline survey, based on the framework by Wells (1998), was used to collect data of native British English speakers’ pronunciation preferencesconcerning the phonetic changes. Pronunciation variants of the words seen in Table-1 were presented in a multi-choice format. The survey was completed by 64 respondents of both sexes belonging to different age groups. The findings were descriptively analysed to determine some likely tendencies in current General British pronunciation.

The second stage was to perform a comparative analysis of the manifestation of the phonetic changes in three pronouncing differences: Longman Pronunciation Dictionary 3rded. (2008), Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary 18th ed. (2011), and Current British English Searchable Transcriptions (CUBE) (N/A). The dictionaries claimed to “provide information on the current pronunciation” (CEPD2011, p. v). Their comparison, thus, could highlight some tendencies in the acceptance and degrees of changes in a model of British English characteristic of educated adults.

Prevalence of four phonetic changes in General British

Survey results

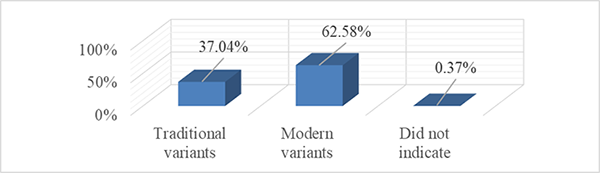

The survey results from 64 respondents yielded a nearly 100 per cent overall responserate.There were less than one per cent (0.37) answers without a marked preference, while the ratio of modern to traditional variants was 1.7 to 1,i.e., 62.58 to 37.04 per cent respectively(Fig.-1).

Figure-1: Preferences for traditional and modern variants in the survey.

The analysis according to phonetic changes, however, indicated an uneven distribution of preferences. While the traditional variants prevailed in one set of lexical items, recent innovations were consistently preferred in other categories. 30 out of 64 respondents (46.88 per cent) showed a relatively strong preference for retaining the traditional /Cju:(ʊ)/ sequences while an opposite tendency was observed for the analysed words from the GOAT lexical set.

3.1.1. Yodcoalescence and yod dropping

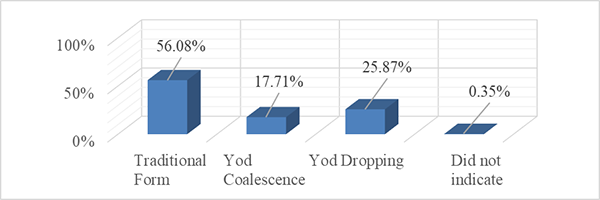

Contrary to the overall survey tendencies, the results for /Cju:(ʊ)/ sequences showed the traditional forms to be the prevalent choice (56.08 per cent), being 3.2 and 2.2 times more common than yod coalescence and yod dropping respectively (Fig.-2). The latter two were indicative of phonetic changes, and grouped together, composed a total of 43.58 per cent, reducing the ratio of traditional to modern variants to 1.3 to 1.

Figure-2: Preferences for /Cju:(ʊ)/ sequences in the survey.

Some patterns started to emerge during theexamination of the phonetic changes. For example, yod dropping was noticedto be commonin two-syllable words with the stress on the second syllable, with ‘induce’ being an exception. Two-syllable verbs with a Latin-origin root -sumeproved to have little resilience to change with 51.37 per cent preference rate for modern pronunciation.

Yod coalescence was most likely to take place in the mid position of four-syllable words with the primary stress on the third syllable.The word ‘situation,’ with only 32.81 per cent preference for the traditional pronunciation,could be used to exemplify the tendency.

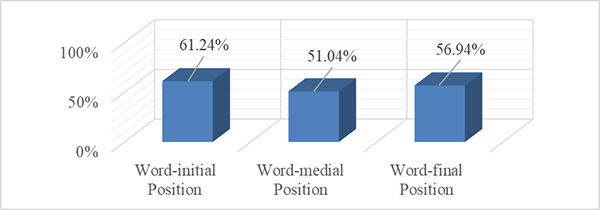

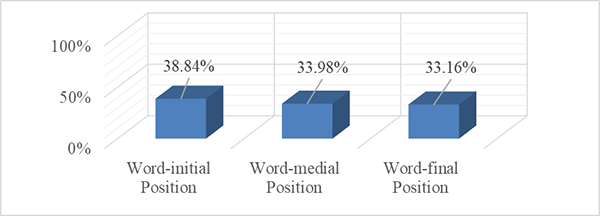

The distribution of traditional variant preferences according to word position can be seen in Figure-3.

Figure-3: Preferences for traditional variants based on the position of the consonant cluster in the survey.

In all the positions, traditional variants constituted more than a half, ranging between 61.24 per cent for the most conservative word-initial and 51.04 per cent for the least conservative word-medial position. The ratios between the traditional variants of consonant clusters occurring in word-initial position and word-medial and final positions were only 1.2 and 1.1 to 1, respectively.

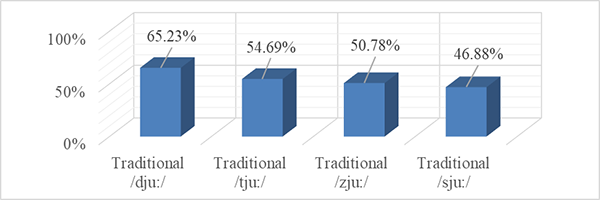

Figure-4: Preference for traditional consonant clusters in the survey.

As the data in Fig.-4 suggest, some correlation might exist between the preference for the traditional pronunciation and the consonant cluster. The clusters with alveolar plosives were more likely to remain unchanged. In 59.96 per cent of the examined cases, the traditional /dju:/ and /tju:/ variants were prioritised, the number being 48.83 per cent for the clusters with alveolar fricatives, i.e.,the modern pronunciation of the latter type being 1.3 times more frequent. Voicing of the first cluster element seemed also to play a role. The clusters with a lenis first element (/dj/ and /zj/) were less prone to changes than in the case of a fortis first element (/tj/ and /sj/), with the ratio of 1.2 and 1.1 to 1, respectively.

3.1.2. Loan words

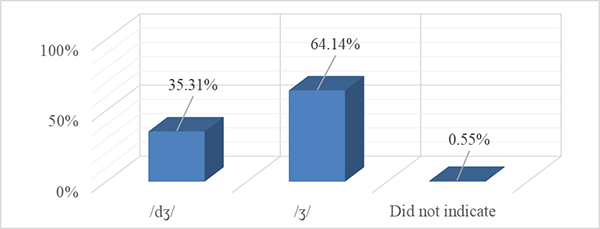

Figure-5 shows the distribution of the preferred forms for loan words with /ʒ/ and /dʒ/.

Figure-5: Preferences for anglicised vs. non-anglicised forms in loan words in the survey.

The non-anglicised /ʒ/ was 1.8 times more frequent than the traditional /dʒ/ variant. The analysis of individual words suggested some emerging patterns. The majority of the respondents chose /ʒ/ in the words with the suffix ‘-age’. The modern forms of ‘barrage’, ‘camouflage’, ‘espionage’, and ‘massage’ accumulated a total of 72.55 per cent making them 2.6 more common than the traditional anglicised ones.

The only two cases where the preferences distributed rather evenly werecommonly used nouns ‘journal’ and ‘jargon’. The time when the words entered the English language and the frequency of their use seemed to have direct correlation with thelikelihood to have ananglicised variant. The third noun starting with the letter <j>, ‘jabot’, a more recent addition to English, failed to follow the same trend. Most of the survey participants (68.75 per cent) expressed their preference for the modern non-anglicised variant.

‘Management’ (56.25 per cent) and ‘gauge’ (53.13 per cent) stood out as the only items with the preferred anglicised variants. Though the word ‘lingerie’ shares the number of syllables and the stress pattern with ‘management’, it yielded only 31.25 per cent preference for /dʒ/, supporting the hypothesis of correlation between word frequency and its inclination to change.

The survey results showed that the words of the Italian origin had an average of 45.31 per cent rate in favour of traditional variants, those of the French origin having an average of 34.5 per cent. Since the /dʒ/ phoneme is more common in Italian and /ʒ/ in French pronunciation, it is likely that the origin of the word could influence the preferences.

The stress might have played a role on the respondents’ preference. Two-syllable words with the primary stress on the second syllable proved to be more prone to phonetic change than with the first syllable stressed (25.78 and 35.00 per cent of traditional variants respectively).For example, for the word ‘regime’ 85.93 per cent of the respondents favoured the modern variant.

In this lexical set as a whole, the position of the observed change seemed to have no impact on the preference (Fig. 6). Retaining traditional forms in the front position of the examined words was only 1.1. times more common than in both medial and final positions.

Figure-6: Preferences for traditional variants according to the position of the phoneme in the survey.

The analysis of individual profiles suggested that most of the respondents were quite consistent in their choices: the participants either chose one phoneme and applied it throughout the lexical set or used both phonemes systematically. For example, some of the respondents selected /dʒ/ in the front and /ʒ/ in the final position.

3.1.3. GOAT allophony

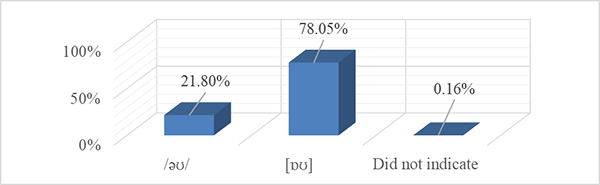

The last examined change, the substitution of the traditional /əʊ/ diphthong with [ɒʊ] before dark /l/,falls under the heading of ‘recent trends.’

Figure-7: Preferences for diphthongs before the dark /l/ in the survey.

As can be seen in Fig.-7, the majority of the informants (78.05 per cent) selected [ɒʊ] as their preferred option, making it 3.6 times more frequent than the conventional /əʊ/. Consistency was characteristic of this analysed data set. 28 profiles out of 64 (43.75 per cent) were categorical in their preferences and chose either traditional or modern variants at a 100 per cent rate. 18 out of 64 profiles (28.13 per cent) prioritised one variant, choosing the second variant from one to five times. An overall of 71.88 per cent of the respondents were static in their choices. The individual profiles that were not consistent tended to opt for traditional forms of either ‘wholly’ (26.56 per cent) or ‘holy’ (29.69 per cent). These were the only two-syllable words analysed. It is difficult to determine whether this could have influenced the slightly higher preference for the /əʊ/ sound. The possibility that the preceding fricative /h/ might have impacted the favoured pronunciation is not excluded, however, the conventional form for the word ‘hole’ was slightly less popular (23.44 per cent). It is likely that it is a matter of semantics and in what kind of contexts the word ‘holy’ is used. The necessity to distinguish this word would make it a minimal pair with ‘wholly’ rather than a homophone, nonetheless, further investigation is necessary to confirm these theories.

Orthographically, /əʊ/ or [ɒʊ] can be spelled with<o>(‘gold’), <ou>(‘mould’), <oa>(‘goal’), or <ow>(‘bowl’). Spelling differences, however, did not seem to influence the preferences.

3.2. The four changes in the pronunciation dictionaries

3.2.1. Yod coalescence and yod dropping

Table-2 provides the manifestation of phonetic changes in Cju:(ʊ)/ sequences in the three phonetic dictionaries.

Table-2: /Cju:(ʊ)/ sequences in LPD, CEPD, and CUBE dictionaries (‘C’ = coalescence, ‘E’=elision, ‘T’ = traditional variant).

LPD |

CEPD |

CUBE |

|||

Word |

1st |

2nd |

1st |

2nd |

The only |

assume |

əsjuːm |

C/E |

əsjuːm |

E |

əsjuːm |

attitude |

ætɪtjuːd |

C |

ætɪtʃuːd |

T |

ætɪʧuːd |

constitution |

kɒntstɪtjuːʃən |

C |

kɒntstɪtʃuːʃən |

T |

kɒnstɪʧuːʃən |

consume |

kənsjuːm |

C/E |

kənsjuːm |

E |

kənsjuːm |

costume |

kɒstjuːm |

C |

kɒstʃuːm |

T |

kɒsʧuːm |

destitute |

destɪtjuːt |

C |

destɪtʃuːt |

T |

destɪʧuːt |

due |

djuː |

C |

dʒuː |

T |

ʤuː |

duel |

djuːəl |

C |

dʒuːəl |

T |

ʤuːəl |

duke |

djuːk |

C |

dʒuːk |

T |

ʤuːk |

dune |

djuːn |

C |

dʒuːn |

T |

ʤuːn |

duty |

djuːti |

C |

dʒuːti |

T |

ʤuːtiː |

education |

edjʊkeɪʃən |

C |

edʒʊkeɪʃən |

T |

eʤəkeɪʃən |

induce |

ɪndjuːs |

C |

ɪndʒuːs |

T |

ɪnʤuːs |

module |

mɒdjuːl |

C |

mɒdjuːl |

C |

mɒʤuːl |

presume |

prɪzjuːm |

C/E |

prɪzjuːm |

E |

prɪzjuːm |

resume |

rizjuːm |

C/E |

rizjuːm |

E |

rɪzjuːm |

situation |

sɪtʃʊeɪʃən |

T/E |

sɪtjʊeɪʃən |

C |

sɪʧuːeɪʃən |

tube |

tjuːb |

C |

tʃuːb |

T |

ʧuːb |

Tuesday |

tjuːzdeɪ |

C |

tʃuːzdeɪ |

T |

ʧuːzdeɪ |

tune |

tjuːn |

C |

tʃuːn |

T |

ʧuːn |

Published in 2008, LPD prioritised the traditional forms in all the words except ‘situation’, where the coalesced variant was presented first. In a 2011 edition of CEPD, the number for prioritised traditional forms dropped to six out of 20. In CUBE, which is “phonetically up to date” the number for traditional forms decreased to four.

Contrary to the survey results, the consonant clusters with alveolar plosives proved to be more prone to change than consonant clusters with alveolar fricatives. The word ‘situation’ stood out as the only example with a change from a modern (LPD) to traditional (CEPD), and back to modern (CUBE) variant. Such a fluctuation might indicate that the phonetic change, though defined as ‘almost complete’, has not reached its final stage. For the word ‘module,’ it took longer for the change to be documented. The modern variant was provided in CUBE only.

LPD and CEPD presented secondary optionsto some extent. For example, in LPD, yod coalescence was suggested as a possible alternative throughout the examined lexical set. Elision, on the other hand, appeared only in five out of 20 entries. This did not accord with the tendencies of the survey, where yod dropping was more prevalent than coalescence. As shown in Table-2, the instances of elisionin both LPD and CEPD were the verbs with the Latin root -sume. In the survey, these were the only four words with the preferred modern variants, especially the elided forms, alluding to /sju:/ and /zju:/ sequences in the final syllable being more prone to change.

3.2.2. Loan words

Manifestations of a ‘well established” phonetic change of /dʒ/ and/ʒ/ in French and Italian origin loan words are presented in Table-3.

Table-3: /dʒ/ and/ʒ/ in loan words inLPD, CEPD, and CUBE dictionaries.

LPD |

CEPD |

CUBE |

|||

Word |

1st |

2nd |

1st |

2nd |

The only |

adagio |

ədɑːdʒɪəʊ |

-ʒ- |

ədɑːdʒɪəʊ |

-ʒ- |

ədɑːʤiːəʊ |

barrage |

bærɑːʒ |

-dʒ |

bærɑːdʒ |

- |

bærɑːʒ |

Beige |

beɪʒ |

- |

beɪʒ |

- |

beɪʒ |

camouflage |

kæməflɑːʒ |

-dʒ |

kæməflɑːʒ |

- |

kæməflɑːʒ |

Doge |

dəʊdʒ |

-ʒ |

dəʊdʒ |

-ʒ |

dəʊʤ |

espionage |

espɪənɑːʒ |

-dʒ |

espɪənɑːʒ |

-dʒ |

espiːənɑːʒ |

Gauge |

ɡeɪdʒ |

- |

ɡeɪdʒ |

- |

geɪʤ |

gelatine |

dʒelətiːn |

- |

dʒelətiːn |

- |

ʤelətiːn |

Genre |

ʒɒnrə |

dʒ- |

ʒɑ̃ːnrə |

- |

ʒɒnrə |

Gigolo |

dʒɪɡələʊ |

ʒ- |

dʒɪɡələʊ |

ʒ- |

ʒɪgələʊ |

Gigue |

ʒiːɡ |

- |

ʒiːɡ |

- |

ʒiːg |

Jabot |

ʒæbəʊ |

- |

ʒæbəʊ |

- |

ʒæbəʊ |

jargon |

dʒɑːɡən |

- |

dʒɑːɡən |

- |

ʤɑːgən |

journal |

dʒɜːnəl |

- |

dʒɜːnəl |

- |

ʤɜːnəl |

lingerie |

lændʒəri |

- |

lænʒəri |

-dʒ- |

lænʒəriː |

management |

mænɪdʒmənt |

- |

mænɪdʒmənt |

- |

mænɪʤmənt |

massage |

mæsɑːʒ |

-dʒ |

mæsɑːdʒ |

- |

mæsɑːʒ |

prestige |

prestiːʒ |

-dʒ |

prestiːʒ |

- |

prestiːʒ |

regime |

reɪʒiːm |

-dʒ- |

reɪʒiːm |

- |

reɪʒiːm |

Rouge |

ruːʒ |

- |

ruːʒ |

- |

ruːʒ |

The modern non-anglicised first variants with /ʒ/ occurred11, 10, and 13 times out of 20 in LPD, CEPD and CUBE, respectively. The survey results indicated the preference for modern forms in the words ending in -age, which matched the CUBE data. While LPD consistently suggested /ʒ/ and provided /dʒ/ as a secondoption, CEPD results weremore flexible. For example, ‘barrage’ and ‘massage’ were presented in their anglicised variants without any alternatives. ‘Camouflage’ and ‘espionage’ were presented with/ʒ/ in the final position, a second variant provided for the word ‘espionage’ only.

The degree of providing secondary variants for the word set under analysis varied from ten in LPD to none in CUBE, with five in CEPD.The only example of a mismatch of the variants in LPD and CEPD was the word ‘lingerie.’ LPD provided only the traditional variant, while in CEPD, it wassuggested as an alternative.

The survey indicated almost equal preference for anglicised and non-anglicised variants of ‘jargon’ and ‘journal’ while all the analysed dictionaries unanimously suggested the anglicised variants. The majority of the prioritised variants, however, reflected the tendencies of the conducted survey.

3.2.3. GOAT allophony

GOAT allophonyfalls under the category of ‘recent’phonetic trends. Its manifestation in pronunciation dictionaries is presented in Table-4.

Table-4: GOATallophony in LPD, CEPD, and CUBE dictionaries.

LPD |

CEPD |

CUBE |

||

Word |

1st |

2nd

|

The only variant |

The only variant |

Bold |

bəʊld |

ɒʊ |

bəʊld |

bəʊld |

Bolt |

bəʊlt |

ɒʊ |

bəʊlt |

bəʊlt |

Bowl |

bəʊl |

ɒʊ |

bəʊl |

bəʊl |

Coal |

kəʊl |

ɒʊ |

kəʊl |

kəʊl |

Cold |

kəʊld |

ɒʊ |

kəʊld |

kəʊld |

Fold |

fəʊld |

ɒʊ |

fəʊld |

fəʊld |

Goal |

ɡəʊl |

ɒʊ |

ɡəʊl |

ɡəʊl |

Gold |

ɡəʊld |

ɒʊ |

ɡəʊld |

ɡəʊld |

Hole |

həʊl |

ɒʊ |

həʊl |

həʊl |

Holy |

həʊli |

- |

həʊli |

həʊli: |

Mould |

məʊld |

ɒʊ |

məʊld |

məʊld |

Moult |

məʊlt |

ɒʊ |

məʊlt |

məʊlt |

Old |

əʊld |

ɒʊ |

əʊld |

əʊld |

Role |

rəʊl |

ɒʊ |

rəʊl |

rəʊl |

Roll |

rəʊl |

ɒʊ |

rəʊl |

rəʊl |

Shoal |

ʃəʊl |

ɒʊ |

ʃəʊl |

ʃəʊl |

Sole |

səʊl |

ɒʊ |

səʊl |

səʊl |

Soul |

səʊl |

ɒʊ |

səʊl |

səʊl |

Told |

təʊld |

ɒʊ |

təʊld |

təʊld |

Wholly |

həʊli |

ɒʊ |

həʊli |

həʊl+li: |

Both CEPD and CUBE limited their entries to traditional variants. LPD was the only dictionary providing the second variant with the innovative diphthong [ɒʊ] (‘holy’ being an exception).This contrasted with the survey findings, where the traditional form was prioritised more than 3.5 less than the modern variant.

Discussion and conclusions

Nowadays, non-native language learners have a plethora of learning resources and a wide range of exposure to spoken English. New words enter English on a regular basis, and people easily adopt them (e.g. COVID-related vocabulary). Changes in pronunciation might be slower to reach language learners, not only because they are not fully documented in non-specialised dictionaries, but also because an ordinary person would not consult a dictionary to check the pronunciation of a well-known word, e.g. ‘student’ (/ˈstjuː.dənt/ in the Cambridge Dictionary Online but /sʧuːdənt/in CUBE). It might be beneficial to make learners aware of the phonetic changes and show how the so-called standard has changed. The present pilot study was an attempt at comparing the degree of documentation of four phonetic changes in three 21st century pronunciation dictionaries. It also aimed at checking the scope of acceptance of the changes by native speakers.Yod coalescence, yod dropping, de-anglicisation of loan words, and GOAT allophony showed the signs of having entered General British, the current standard of British English.

The survey analysis of 60 lexical itemscategorised on the basis of their shared phonetic qualities revealed that most respondents showed a strong preference for the ‘modern’ pronunciation variants.Examination of individual profiles, however, suggesteda different degree of disposition to accept the changes.While the set of words assigned to the category of ‘almost complete’ changes, i.e. yod coalescence and yod dropping,was relatively more likely to retain their traditional forms than the words from other categories, the inside-category results were not homogenous. The /dj/ cluster proved to be the most resistant to change. The other examined sets showed more homogeneity.GOAT allophony word group, surprisingly, turned out to be the most ‘modern’ analysed set. Even thoughthe change has only recently been introduced into General British, this pilot study might be indicative ofit beinga widespread phenomenon among native speakers.

The comparative analysis of the three pronunciation dictionaries witnessed the undergoing process of phonetic change. Though all the compared dictionaries were of the 21st century, the comparison highlighted the rapid development of changes. The overall results indicated a direct correlation between the year of publication (or an update in the case of the online dictionary CUBE) and the degree of the spread of the changes. LPD stood out as the mostreflective in terms of documented variants, yet strongly prioritising traditional pronunciation (80 per cent of the analysed words). CEPD and CUBE, on the other hand, proved to be more likely to document ‘modern’ variants (except for GOAT allophony).Prioritisation of traditional variants was only 26.7 per cent in CEPD. Although CUBE provided no secondary variants for any of the analysed words, it might be considered to be the most up-to-date pronunciation dictionary available.

References

CARLEY, P., MEES, I. M. & COLLINS, B., 2018. English Phonetics and Pronunciation Practice. London & New York: Routledge.

COLLINS, B, MEES, I. M., 2013. Practical Phonetics and Phonology. 3rd ed. London & New York: Routledge.

CRUTTENDEN, A., 2014. Gimson‘s Pronunciation of English. 8th ed. London & New York: Routledge.

ELLIS, A. J., 1869. On Early English Pronunciation, With Especial Reference to Shakespeareand Chaucer. London & Berlin: Asher & Co. Available from: URL https://archive.org/details/onearlyenglishp02winkgoog/page/n36/mode/2up (accessed on January 27, 2020).

GLAIN, O., 2012. The Yod /j/: Palatalise It Or Drop It!: How Traditional Yod Forms are Disappearing from Contemporary English. Cercles, 22, 4–24. Available from: URL https://www.cercles.com/n22/glain.pdf (accessed on November 25, 2019).

HANNISDAL, B. R., 2006. Variability and change in Received Pronunciation. Bergen: University of Bergen. Available from: URL https://bora.uib.no/bora-xmlui/bitstream/handle/1956/2335/Dr.Avh.Bente%20Hannisdal.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on September 12, 2019).

HARRINGTON, J., KLEBER, F., & REUBOLD, U., 2011. The contributions of the lips and the tongue to the diachronic fronting of high back vowels in Standard Southern British English. Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 41(2),137–156. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025100310000265

JONES, D., 1917. Everyman’s English Pronouncing Dictionary (1st ed.). London: The Aldine Press. Available from: URL https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.93283/page/n17/mode/2up (accessed on January 27, 2020).

JONES, D., 2006. Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary. 17th ed. Edited by P. ROACH, J. HARTMAN & J. SETTER. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

KACHRU, B. B., 1985. Standards, codification and sociolinguistic realism: the English language in the outer circle. In: R. QUIRK & H.G. WIDDOWSON (Eds.). English in the world: Teaching and learning the language and literatures. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 11–30.

KACHRU, B. B., 1998. English as an Asian language. Links & letters, 5, 89–108. Available from: file:///C:/Users/lbike/AppData/Local/Temp/22673-Article%20Text-22597-1-10-20060309.pdf (accessed on December 10, 2020).

KORTMANN. B., 2020. English Linguistics. Essentials. 2nd ed. Berlin: J.B.Metzler Verlag.

LEV-ARI, SH., KEYSAR, B., 2010. Why don’t we believe non-native speakers? The influence of accent on credibility. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 46(6), 1093–1096. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2010.05.025.

LEVEY, D., 2014. Some recent changes and developments in British English. In: R. MONROY-CASAS & I. ARBOLEDA-GIRAO (Eds.). Readings in English Phonetics and Phonology.Universitat de Valencia, IULMA, 385–405.

LINDSEY, G., 2019. English After RP: Standard British Pronunciation Today. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

LOCKER, M. A., STRÄSSLER, J., 2008. Introduction: Standards and norms. In: M. LOCKER & M. A. STRÄSSLER (Eds.). Standards and Norms in the English Language. Berlin & New York: Mouton de Gruyter, 1–20.

LOW, E.-L., 2015. Pronunciation for English as an International Language. From research to practice. London & New York: Routledge.

MORENO FALCÓN, M., 2017. Watching RP change. An acoustic sociophonetic study of theKIT/schwa shift, GOOSE fronting and the monophthongisation of /ʊə, eə, ɪə/ into /ɔː, ːɜ, ɪː/. Available from: URL https://www.researchgate.net/publication/319713382_Watching_RP_change_an_acoustic_sociophonetic_study_of_the_KITschwa_shift_GOOSE-fronting_and_the_monophthongisation_of_e_I_into_I (accessed on February 11, 2020).

MOTT, B., 2014. Recent changes in English phonetics and their representation in phonetic notation. In: R. MONROY-CASAS & I. ARBOLEDA-GIRAO (Eds.). Readings in English Phonetics and Phonology. Universitat de Valencia, IULMA, 369–384.

ROACH, P., 2009. English Phonetics and Phonology. 4th ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

SAUER, W., 2002. Some recent developments in standard British English pronunciation and the teaching of EFL. Available from: URL http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.413.3394andrep=rep1andtype=pdf (accessed on December 12, 2020).

TRUDGILL, P., 2000. Sociolinguistics: an introduction to language and society. 4th ed.

London: Penguin.

TRUDGILL, P., 2001. The sociolinguistics of modern RP. Sociolinguistic Variation and Change. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

TRUDGILL, P., HANNAH, J., 2008. International English: A guide to varieties of Standard English. 4 ed. London: Hodder Arnold.

UPTON, C., 2004. Received Pronunciation. In: E. SCHNEIDER et al. (Eds.). A handbook of varieties of English. Volume 1: Phonology. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 217–230.

WELLS, J. C., 1982. Accents of English. Cambridge &New York: Cambridge University Press.

WELLS, J.C., 2000. Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. New edition. London: Longman.

Sources

Cambridge Dictionary Online. Available at: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/.

LINDSEY, G., SZIGETVÁRI, P., N/A. Current British English Searchable Transcriptions. Available at: http://cubedictionary.org/.

ROACH, P., HARTMAN, J., SETTER, J., & JONES, D., 2011. Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary. 18th ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

WELLS, J. C., 2008. Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. 3rd ed. Pearson Longman.

Lina Bikelienė: Assoc. Prof., Dr., Vilnius University, Universiteto 5, Vilnius, +37065177771, lina.bikeliene@flf.vu.lt.

Laura Černelytė: Student, Vilnius University, Universiteto 5, Vilnius, +37052687264, laura.cernelyte@uki.stud.vu.lt.