Analysis of English-Spanish False Friends

Lina Inčiuraitė-Noreikienė

Vilnius University,

Universiteto 5, Vilnius,

Lithuania

Email: lina.inciuraite@flf.vu.lt

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4002-5224

Research Interests: word formation, morphology, English language teaching.

Deimantė Šarkaitė

Vilnius

University

Universiteto 5, Vilnius, Lithuania

Email: deimante.sarkaite@flf.vu.lt

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5471-0433

Research Interests: bilingualism, misuse of foreign language, second language acquisition.

Abstract. The present study aims to carry out an analysis of English-Spanish false friends in order to establish the most prevailing type of false friends and to determine their degree of falseness and semantic resemblance. Qualitative and quantitative methods were used to conduct the research. The results of the analysis have shown that the most dominant part of speech among false friends in English and Spanish is the category of nouns. The vast majority of false friends share their origins in Latin. The most prevailing type of false friends is semantic total. The data gathered from the questionnaire display that the majority of language users are familiar with the phenomenon and can recognize and understand the meaning of the false friend word pairs.

Key words: false friends, noun, etymology, part of speech, semantic total.

JEL Code: G35

Copyright © 2022 Lina Inčiuraitė-Noreikienė, Deimantė

Šarkaitė. Published by Vilnius

University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the

terms of the Creative

Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use,

distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author

and source are credited.

Pateikta / Submitted on

01.08.22

Introduction

Language learning has been acknowledged as one of the most significant and valuable fields of study, greatly contributing to education and linguistics. Since different languages have been inevitably affected by diachronic changes, the language learning process has become challenging for language learners due to the resemblance of some word pairs that coincide with each other in different aspects.

A lot of attention was brought to the phenomenon of false friends[1] after noticing that ignorance of such words in conversations involving two languages often caused miscommunication and, in some cases, it may have become embarrassing for the speaker. One of the main reasons conversations cease so unsuccessfully is that people tend to overgeneralize their knowledge of the second language (L2) and assume that one word recognizable in their first language (L1) will possess the same meaning, which in many cases, is completely different.

This study aims to carry out an analysis of English-Spanish[2] false friends in order to establish the most prevailing type of false friends and to determine their degree of falseness and semantic resemblance. To achieve this aim, the following objectives have been set: 1) to identify and compare parts of speech and etymology of the selected false friend word pairs in order to elucidate their types, 2) to examine the language learner’s ability to recognize, understand, and detect the mistakes caused by false friends.

1. Literature review

1.1 The notion of false friends

False friends is a notion widely used in most research related to second language acquisition, translation, teaching, and other studies (Al-Athwary, 2021, p. 368) and belongs to one of the most interesting and relevant linguistic topics in recent years. Chamizo-Domínguez (2008, p. 16) defines this notion as a specific phenomenon of linguistic interference consisting of two given words in two or more languages that are graphically and/or phonetically the same or very similar, however, their meanings may be totally or partially different. Roca-Varela (2015, p. 11) provides a similar definition, stating: “False friends (FF henceforth) are lexical items in different languages that resemble each other in form but have different meanings”. Another definition can be obtained from the language teaching (LT) perspective. According to Sales (1998, p. 1), “False friends are words in a target language (L2) whose signifier is similar to (or identical with) the signifier of one or more words in the student’s native language (L1) because they derive from a common etymon”. Consequently, the phenomenon of false friends is studied in different linguistic discourses, yet the definition remains mostly the same.

The notion of false friends has other names that are used as synonyms. Chamizo-Domínguez (2008) and Roca-Varela (2015) propose some other linguistic expressions for this concept such as deceptive cognates, misleading cognates, homographic non-cognates, pseudo cognates, false pairs, deceptive words, false equivalents, interlingual / interlexical homographs, false cognates, and some others. All these terms are used to refer to this linguistic phenomenon, however, they can also mislead, since not all of them can be used interchangeably as the meaning is not identical in all listed cases. Roca-Varela (2015) points out that most studies erroneously use the term false cognates as a synonym for false friends, yet false friends encompass the category of false cognates, but not vice versa. Chamizo-Domínguez (2008) explains that linguistic cognates are used for the words of common etymological origin independently of their meaning. A great example of this definition is conveyed in Roca-Varela’s paper (2015, p. 30): the Spanish word verbo and the English word verb are both cognates that originated from the Latin verbum. However, the author admits (2015, p. 30) that the term false cognate also includes the adjective “false”, therefore the meaning of cognate drastically changes. For example, the Spanish word copa comes from the Latin origin meaning “cup” in English, whereas cup in English comes from the OE (Germanic origin) and means “a drinking container” in Spanish. In the words of Chamizo-Domínguez (2008, p. 3), “false cognates would be a hyponym of false friends”.

1.2 General classification of false friends

It might seem at first that the phenomenon of false friends is not that common in languages, yet Veisbergs (1996, p. 628) admits that false friends as such reach the proportion of 10-20% even in non-related languages, which is quite a high percentage.

False friends are analyzed and discussed from different perspectives since they cover a large scope of various fields of study that linguists are interested in. Therefore, because false friends can be distributed according to varied criteria, there is no exact classification made that everyone could agree on and employ by default. Veisbergs (1996, p. 628) made a classification and separated false friends into the following categories: proper false friends, occasional/accidental false friends, and pseudo false friends. This categorization is more general and surveys the major types of false friends. However, most scholars apply the classification model provided by Chamizo-Domínguez, which is more recent, although this model limits the investigation because it is based on etymology and is more suitable for studies regarding the origin of false friends. Consequently, for more extensive work or in-depth research on a particular topic, this classification alone would not suffice, and various categorizations would be necessary to achieve more accurate data. Roca-Varela (2015, p. 34) brought together specific typologies distinguished by different scholars and categorized them in depth. Those categories encompass: etymological, semantic, pragmatic, grammatical and syntactical, and eclectic classifications.

1.2.1 Etymological classification

Considering the origin of the false friends as the main criterion, Chamizo-Domínguez (2008, p. 4) distinguishes two main categories: chance false friends and semantic false friends. The author defines chance false friends as word pairs in given languages that do not share a common etymology, have different meanings, and are graphically and/or phonetically similar by accident due to random diachronic changes. Graphically similar false friends are called homographs because they have identical or almost the same spelling in both languages (Chamizo-Domínguez, 2008). For instance, the English word red (“colour”) and Spanish red (Eng. “net”, “network”) seem alike, yet carry different meanings. In contrast, homophones are the word pairs that (almost) fully coincide in pronunciation but differ in spelling. For example, a pun in English refers to “a stylistic device used in language to create a humorous effect”, whereas in Spanish pan is pronounced almost the same as a pun but means “bread”. In addition, Al-Athwary (2021, p. 369) proposes an alternative name for chance false friends referring to them as pseudo false friends. He suggests that pseudo false friends are “a product of the L2 imaginations, <…> created based on a false analogy. The L2 learner builds an imaginative lexeme for a native word, thinking that native word must have a similar equivalent in L2.”

1.2.2 Semantic classification

Roca-Varela’s (2015, p. 36) findings revealed that the degree of semantic overlap between the word in L1 and L2 establishes a ranking order and contains three types of false friends that are divided into two main categories of full (or total) semantic false friends and partial semantic false friends. As Chamizo-Domínguez (2008, p. 6) explained: the first type indicates the word pairs in two or more given languages whose meanings are unlike and in no case should be translated by the other. For instance, molest in English means “to harass” or “to abuse sexually”, and in Spanish molestar means “to bother”. The second type refers to the word pairs in two or more given languages that share some meanings but not in all cases, for example, English argument and Spanish argumento[3]. Consequently, semantic false friends refer to the word pairs that are etymologically related, and their source (usually Latin or Greek) could be determined but have developed their meanings in different languages throughout the time due to various reasons (Chamizo-Domínguez, 2008). An example of such word pairs would be fastidious in English meaning “comprehensive” and Spanish fastidioso meaning “boring”. In addition, Chamizo-Domínguez and Nerlich (2002, p. 1833) supplement that semantic false friends “can be considered to be cross-linguistic equivalents to polysemous words in a single natural language” and highlight the importance of studying false friends in order to avoid misunderstandings or mistranslations.

1.2.3 Pragmatic classification

There are pragmatic features that are relevant to the phenomenon of false friends and must be considered while carrying out this classification that has been discussed by various scholars (Roca-Varela, 2015). Granger and Swallow (1988) distinguish such elements as levels of denotation, connotation, register, and formality of similar words in various languages, stylistics, etc. Not only do these components emphasize the importance of the context, the connotations associated with the lexical items in each language, and the social and cultural features of these words, but also, they are periodically neglected in semantic classification. In addition, Gouws, Prinsloo, and Schryver (2004) have contributed to the issue with the distinction of partial false friends in different degrees as well as the various degrees of semantic overlap that include features of difference in stylistic and register, and different frequency of the use of false friends in L1 and L2. Roca-Varela (2015, p. 37) demonstrate this distinction in the English/Spanish example of domicile/domicilio. In English, this word is used in a formal register and belongs particularly to the field of law; whereas in Spanish it has a more general meaning and is a common term to refer to the place of residence, home. Consequently, this example illustrates that pragmatic classification normally includes cognate words not larger than phrases or idioms, which differ in occurring context depending on the formality and frequency of use.

1.2.4 Grammatical and syntactic classification

Scholars have expanded the term false friends to grammar, phraseological units, and structures other than individual lexical items (Roca-Varela, 2015). Although Álvarez Lugrís (1997) determines such false friends at the level of idioms/sayings, syntactic structures, grammatical gender, situations, and connotations, he still hypothesizes that word-level false friends are very common and ambiguous. However, Sheen (1997) distributes grammatical false friends into three types: count/non-count pairs (L1 countable nouns = L2 non-countable nouns or the other way around), similar items in different word classes (word pairs resembling different parts of speech in L1 and L2), and syntactic false friends (verbs of similar meaning and form, ruling a different preposition or no preposition), Al-Wahy’s (2009, p. 104) study of idiomatic false friends between English and Modern Arabic defines this kind of false friends as “pairs of set phrases that have the same literal meaning in two languages but differ as regards their idiomatic meaning or their sociolinguistic and stylistic features”. The author highlights their existence and proposes that idiomatic false friends are not limited to individual lemmas but include various structures and multi-word phrases. Nonetheless, Al-Wahy’s classification could be considered eclectic because it considers and includes various aspects from semantic, pragmatic, and grammatical categorizations (Roca-Varela, 2015).

1.2.5 Eclectic classification

This type of categorization encompasses some of the previously mentioned distributions of false friends made by different scholars. Two distinct classifications from different points of view are reviewed in this section. The first one, by Pinazo Encarnación (1996), includes etymology, formal similarities, and semantic characteristics of various word pairs and classifies false friends into four distinct categories:

- Phonetic false friends – word pairs that fully or almost fully coincide in pronunciation but differ in spelling.

- Graphic false friends – word pairs that have identical or almost the same spelling in both languages.

- False friends derived from loanwords – word pairs that have been borrowed from the source language and have changed meaning in the recipient language.

- Semantic false friends – words of the same origin but different meanings that can be split into total and partial.

Unlike Pinazo Encarnación (1996), Chacón Beltrán (2006, pp. 34–35) emphasizes the lack of research done in the categorization of cognate words and proposes a developed typology of cognates, The CCVF (Clasificación de Cognados Verdaderos y Falsos) is based on three variables: type (true/false cognates), form (graphic/phonetic) and meaning (partial/total/semantic coincidence/divergence). Nevertheless, Roca-Varela (2015, p. 40) narrowed this typology and extracted the four types that are related specifically to false friends: total graphic/phonetic false friends and partial graphic/phonetic false friends. Generally, there is no standard categorization made for false friends even with the numerous attempts, therefore scholars usually apply the classification that respectively corresponds to their subject and field of study.

2. Methodology and data

Qualitative and quantitative methods were used to conduct the research. The qualitative method was used to identify the most common part of speech and etymology, and to determine the degree of false friendship/semantic resemblance of chosen English-Spanish false friend word pairs according to the classification proposed by Roca-Varela (2015). The quantitative method was employed using a questionnaire to generate numeral data and statistics based on participants’ familiarity with the phenomenon as well as to disclose their ability to identify false friends and detect their incorrect usage.

The sample of examples covers 115 English-Spanish investigated word pairs that were found mostly in online content and in some textual handouts. All listed word pairs were arranged alphabetically (see Appendix 1) both in English and Spanish. The fragment on data collection and analysis is provided in Table 1.

Firstly, the part of speech was determined for the selected false friend word pairs; then their meanings[4] were provided. Definitions for English words were taken from Cambridge Advanced Learner’s Dictionary and definitions for Spanish words were taken from DRAE. Their actual meanings were translated using WordReference online translation dictionary and etymology detected with the assistance of OED, The Free Dictionary & DEC[5].

Table 1. The fragment of the analysis of false friends in English and Spanish.

Number |

Word pair |

Part of speech |

Meaning |

Translation |

Etymology |

Type of FF |

11 |

Approve |

Verb |

1. to have a positive opinion of someone or something. 2. to accept, allow, or officially agree to something. |

1. estar de acuerdo 2. aprobar |

Latin |

Semantic partial, semantic overlap |

Aprobar |

Verbo |

1. Calificar o dar por bueno o suficiente algo o a alguien. 2. Obtener la calificación de aprobado en una asignatura o examen. |

1. approve 2. pass |

Latín |

In order to determine if language learners are aware of the linguistic phenomenon of false friends, can recognize them, and avoid mistakes, a questionnaire was constructed. The main criteria for the target audience were that the respondent would know and speak both languages – English and Spanish. The questionnaire was completed by 128 participants (from different countries; from different social, cultural, and academic environments; independently of their sex, age, race or any aspect, yet surrounded by bilingualism). The questionnaire consisted of 30 questions, and tasks were divided into 3 parts. The first part consisted of 7 closed-ended basic introductory questions that generated the statistical background of the target audience. The second part included 10 tasks and asked participants to select one correct word from the given choices. This second part revealed if participants knew false friends. Finally, the last part consisted of 13 miscellaneous exercises: several closed-ended questions, then a closed-ended word bank table in which participants needed to match a word with its meaning, and finally open questions in which they needed to (re)write sentences correctly. The final activity allowed us to examine if participants not only know the meanings of false friends but also if they are able to recognize incorrect usage. A fragment of the questionnaire is presented in Table 2.

Table 2. A fragment of the questionnaire.

1. Gender/Sexo |

2. Age/ |

3. How long have you been learning English?/ |

4. How long have you been learning Spanish?/ ¿Cuánto tiempo lleva aprendiendo español? |

5. What is your mother tongue?/ |

6. Have you ever heard of such linguistic phenomenon as

“false friend(s)”?/ |

Female/Mujer |

25-39 |

For more than 4 years/ |

For more than 4 years/ Por más de 4 años |

Lituano |

Yes, and I know what it means/Sí, y sé lo que significa |

Particular words in the questionnaire were chosen from the 115 samples used in the analysis. The questionnaire focused on the participants’ general knowledge of the phenomenon independently of their native language, including native speakers of one of the target languages, not on their achieved foreign language level. Consequently, the tasks were designed at an open level so that all the respondents would be able to complete them.

Even though 115 samples and 128 results were assembled, some difficulties had been encountered throughout the analysis. The actual number of samples at the beginning of the analysis was higher and reached around 175 samples, however, when the analysis began, some of them were eliminated since not all of them complied with the definition and/or requirements of false friends, and therefore they were not suitable to be regarded as potential samples. This could be explained by pseudo false friends as described by Al-Athwary (2021), because while looking for the accurate false friend word pairs that would be eligible for the analysis, there were lots of lexemes that are a creation of learners’ imaginations and erroneously used based on this false analogy. Therefore, such words cannot operate as the actual false friend word pairs and would impede the selection of the wanted false friends.

3. The analysis of English-Spanish false friends

3.1 Part of speech and etymology of English word pairs

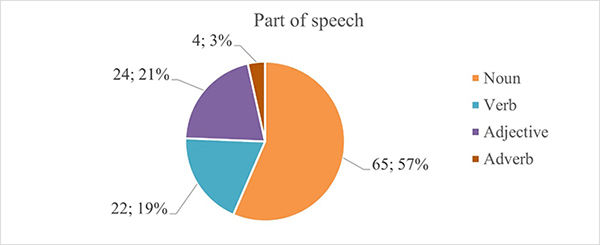

In total 115 different English words have been indicated as false friends and firstly divided according to their part of speech. As is shown in Figure 1, the category of nouns makes up 57% of all data and contains 65 words. Adjectives form 21% of all data and contain 24 words. Verbs, having 22 words, comprise 19% of the data, and surprisingly, have a lower number than was expected initially. Finally, adverbs represent the minority and represent only 4 words, which count for only 3% of the displayed data. As a result, it is obvious that noun false friends lead among the other parts of speech, whereas adjectives and verbs share a very similar number of words, and adverbs stand as a less prominent part of speech among false friends.

Figure 1. Division of English words according to their part of speech.

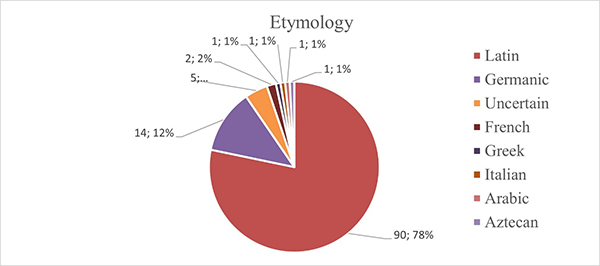

Another division of the words has been made while tracing their etymology. Figure 2 shows the distribution of the various origins detected during the analysis. As is shown in Figure 2, the most common source of origin is Latin, comprising 90 words and 78% of the word list.

Figure 2. Division of English words according to their etymology.

It was not expected to find so many cases of words originating from Latin, yet this finding demonstrates that their emergence into the English language is even higher than it was described by O’Neill and Catalá (1997), and these words have naturally blended into lexis and are currently used. In comparison with Latin, words of Germanic origin account for only 12% of the data, perhaps due to the avalanche of French words that entered the English language. Some of the words contain unknown or uncertain origins, therefore it was not possible to verify them with the help of the dictionary. Only 5 words belong to this category which forms a minority of 4%. Two words were identified as French in origin, which is equal to 2% of the data. The same principle applies to 1 word that belongs to the Italian category. Finally, the minority of the data is followed by the single-entry words that carry only 1% each. Greek, Arabic, Aztecan, and Italian are found in this category. Such etymologies like Arabic or Aztecan were not expected to appear throughout the research as they do not have any correlation with the Germanic languages. Such appearance could be explained only through the lens of a diachronic perspective.

3.2 Parts of speech and etymology of Spanish word pairs

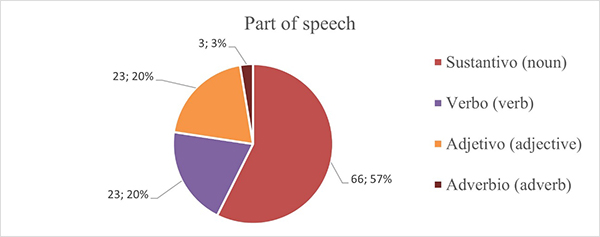

As is reflected in Figure 3, 66 investigated words belong to the noun category, which at 57%, is more than half of the chart. Adjectives and verbs in this division share an equal amount of 23 words and 20% of the data each, whereas adverbs form a minority of 3 words that contribute only 3%. Consequently, nouns solidly represent the majority, meanwhile adjectives and verbs share only one fifth each, and adverbs contain a small minority of the words.

Figure 3. Division of Spanish words according to their part of speech.

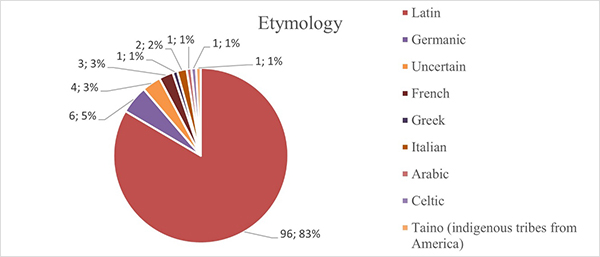

As far as etymology of false friends is concerned, the majority of 96 words carrying the proportion of 83% originated from Latin, which is logical since the Spanish language originated from Latin (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Division of English words according to their etymology.

Unlike Latin, 6 Germanic rooted words resemble only 5% of the data, which means that Germanic words did not penetrate the English language as much as Latin did. There were some words of uncertain origin as well, in total 4 that represents 3%, which is the same percentage as 3 French-origin words. They do fall in the same category with 2 Italian words as in English, which came from a language whose source is unknown. All remaining words are single-entry languages from Greek, Arabic, Celtic, and Taino, and are worth 1%, which illustrates the minority of the cases.

3.3 Determination of false friends type in English-Spanish word pairs

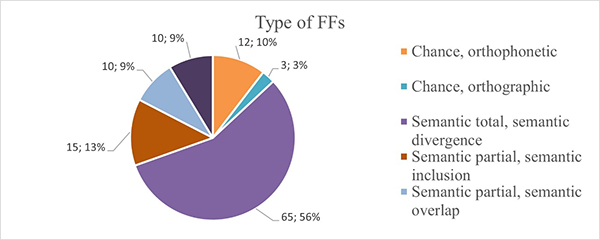

The types of false friends have been allocated based on the proposed categorization by Roca-Varela (Figure 5). As can be seen from the data displayed in Figure 5, semantic total false friends containing 65 words in this category compose more than half (56%) of all word pairs. All other categories except the orthographic chance false friends, which represent the minority of the cases with only 3 words that equal 3%, are distributed almost proportionately.

Figure 5. Distribution of false friends according to their typology.

Partial semantic false friends of semantic inclusion have the highest prevalence among these, consisting of 15 word pairs that form 13% of the data, meanwhile partial semantic of semantic overlap and pragmatic contextual false friends share 10 word pairs of 9% each. Lastly, ortho-phonetic chance false friends with 12 cases of such type contribute 10% to the data. Semantic total false friends establish the majority in the frequency of the word pairs, which means that they need to be learned, otherwise there is a high probability to confuse the words and be misunderstood, whereas orthographic false friends form a minority between the two languages and all other categories of false friends share approximately equal number of word pairs.

4. Examination of the questionnaire

4.1 Language users and their relationship with the phenomenon

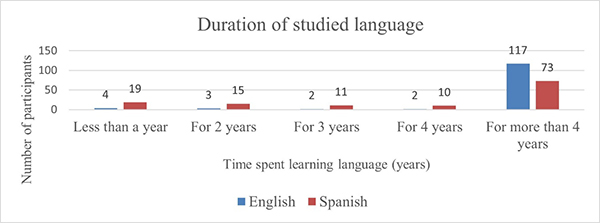

Assembled data shows that of the 128 participants, 80 were women (62.5%), 47 were men (36.7%) and only one person (0.8%) chose not to reveal a gender. The youngest age range (18-24) is represented by 61 people and makes almost half (47.7%) of all respondents. 52 people belong in the age range of 25-39 and makes 40.6%. The mature age range of 40-59 has 14 members with 10.9%, and only one person indicated the category of 60 and over, which is 0.8% of the data. Figure 6 presents the distribution of the years spent while learning one of the target languages.

Figure 6. Duration of the studied language.

The bar chart indicates that most of the participants (117, 91.4%) learned English for more than 4 years and less than 10% studied for a shorter period. However, the data slightly differs when we look at the Spanish statistics.

A number of participants (73 people, 57%) confess that they studied Spanish for more than 4 years, which is about 40% less than English learners, yet 19 people or nearly 15% have been studying Spanish for less than a year. This number is almost 5 times larger than the amount of people learning English in the same category.

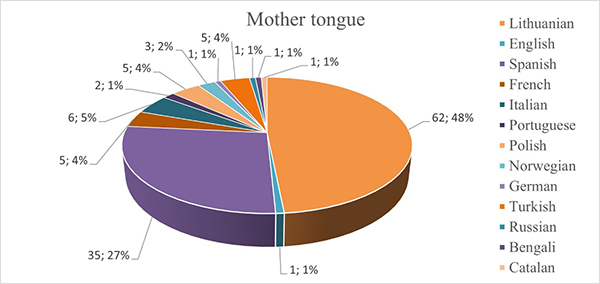

As illustrated in Figure 7, more than half (62.48%) of the participants’ native language is Lithuanian, followed by Spanish with 35 people that make up almost a third (27%) of the chart. Smaller pieces of around 5% each belong to French, Italian, Polish, and Turkish, which make a major part of the overall minority. All other languages except Portuguese and Norwegian have 1 person each and account for only 1%, including English as a mother tongue.

Figure 7. Mother tongue of the participants.

The first part of the questionnaire ends with these two questions: 1) Have you ever heard of such linguistic phenomenon as “false friend(s)” and 2) How often do you confuse the words in foreign language(s) just because they sound or appear similar as in the other language that you speak? When answering the first question, two thirds (64.1%) of 82 participants answered positively that they have heard about the phenomenon and know what it means, and only 13 people (10.2%) answered that they heard of the phenomenon but do not know its meaning. A quarter (25.8%) of 33 participants responded negatively, which means that they had neither heard of it nor do they know what it stands for. As for the second question, around 60% of respondents (73) confess that sometimes they confuse words in different languages because of their similarities, yet 37 people or approximately one third of the results (28.9%) affirm that they seldom confuse such word pairs and the small number of 5 people (3.9%) state that they are never mistaken. Finally, one tenth (10.2%) or 13 people indicated they become confused quite often.

4.2 Findings of the word-meaning matching exercises

The results of the second part of the questionnaire are to be discussed next. The following exercises contained words that had to be provided with the correct meanings. In Table 3 below all 10 listed words are presented together with the numeric data of their respondence and the correct answer bolded and highlighted in yellow.

Table 3. Results of the meaning matching to a word task.

CARPET |

DORMITORY |

EXIT |

(TO) CHOKE |

(TO) INTRODUCE |

Alfombra – 115 (89,8%) |

El saco de dormir – 8 (6,3%) |

Éxito – 5 (3,9%) |

Conmocionar – 20 (15,6%) |

Presentar – 99 (77,3%) |

Carpeta – 13 (10,2%) |

Dormitorio – 90 (70,3%) |

Salida – 122 (95,3%) |

Chocar – 19 (14,8%) |

Introducir – 29 (22,7%) |

Cortina – 0 |

Cuarto – 30 (23,4%) |

Suceso – 1 (0,8%) |

Ahogarse - 89 (69,5%) |

Extraer - 0 |

BIZARRO |

PARIENTE |

SUCESO |

EMBARAZADA |

ACTUALMENTE |

Weird – 57 (44,5%) |

Acquaintance – 17 (13,3%) |

Success – 28 (21,9%) |

Pregnant – 117 (91,4%) |

Actually – 30 (23,4%) |

Bizarre – 47 (36,7%) |

Relative – 99 (77,3%) |

Suicide – 9 (7%) |

Embarrassed – 10 (7,8%) |

Inreality/now – 80 (62,5%) |

Brave – 24 (18,8%) |

Parent – 12 (9,4%) |

Event – 91 (71,1%) |

Understandable – 1 (0,8%) |

In fact -18 (14,1%) |

The first part of the table contains English words with their Spanish meanings, whereas the second part contains Spanish words with English choices. As is displayed in Table 3, meanings for the 5 words in the first row: CARPET, DORMITORY, EXIT, (TO) CHOKE, and (TO) INTRODUCE[6], were selected mostly correctly as they received the highest number of selected answers among all possible answers. Likewise the meanings for the Spanish words PARIENTE, SUCESO, EMBARAZADA, and ACTUALMENTE, were selected correctly, although the word BIZARRO is excluded due to its perplexity. The correct answer for this equivalent was chosen only by the minority of the participants, which indicated that most of the users were not familiar with the word itself and its meaning, or they just got caught in the casual false friends’ trap. Additionally, it is worth mentioning that there was an accidental mistake concerning the final word of this part of the questionnaire– ACTUALMENTE. The correct answer is now[7] but instead, it was written in fact. Since the survey had already begun and some of the answers had already been submitted, the results were split between these two answers, which are equated and considered as one. That is the reason both are separated by a slash and provided as a correct answer in the table. To sum up, it is evident that language learners have great skills in lexis since they can detect and match the correct meaning to the word and avoid being mistaken and misunderstood.

4.3 Findings of the miscellaneous exercises

The final part of the survey incorporated miscellaneous exercises. The task that was designed for the first five questions of this part was to choose the correct sentence from two given (one of them misused a FF or an incorrect word was used instead). The data assembled from this task is displayed in Table 4. The correct sentence is written in blue.

Table 4. Results of the task to choose a correct sentence.

SENTENCE |

CORRESPONDANCE |

Tengo que colectar los libros de la biblioteca para mis deberes. |

10 (7,8%) |

Tengo que recoger los libros de la biblioteca para mis deberes. |

118 (92,2%) |

Ya hace tres meses desde cuando quitó a fumar. |

18 (14,1%) |

Él dejó de fumar hace tres meses. |

110 (85,9%) |

María está al cargo de los asuntos relativos al medio ambiente. |

110 (85,9%) |

María está relativa de la familia real. |

18 (14,1%) |

La calificación de tu examen es 8. |

73 (57%) |

El equipo no calificó para el partido de la liga en Inglaterra. |

55 (43%) |

La chica estaba molestando por su padre por 4 meses. |

16 (12,5%) |

A él le molestaba muchísimo el ruido que hizo el vecino. |

112 (87,5%) |

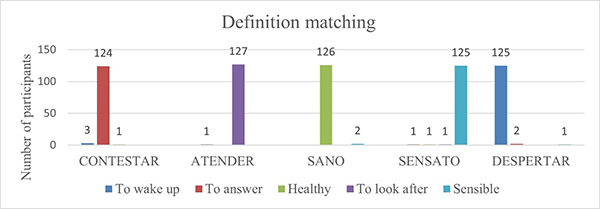

The same applies to the following task of matching a word with its definition. Figure 8 illustrates that participants found no difficulty in matching a definition to its proper word as the number of incorrect answers is very low (maximum of 3 incorrect answers). Consequently, once again the results show that language learners are perfectly able to detect a misuse in each sentence, relate it with the correct word, and are acquainted with the vocabulary items of both languages since they can determine the appropriate definition of the word.

Figure 8. Task of matching a word with its definition.

The results of the last set of the given tasks are presented in Table 5. Since the task required participants to rewrite the sentences in Spanish or English and indicate whether the sentence is correct, the analysis of the results was more complicated owing to various interpretations reflected by the participants. However, the main focus of the task was to find out if the language learners could identify the implicated false friend (that stands for an exact word) and rewrite it correctly (FF is bolded and the corresponding, expected word is highlighted in purple). Therefore, the results will be depicted based on the appointed term.

Table 5. Results of the sentence writing task.

SENTENCE |

RESULT |

Only when I have reached the bus stop, I realized that I left my phone at home. (DARSE CUENTA) |

darse cuenta – 97 recordar – 1 encontrar – 2 entender – 5 saber – 1 descubrir – 2 realizar – 1 acordarse – 1 enterarse – 3 recoger – 1 notar – 3 fijar – 1 comprender – 1 N/A – 9 |

I am going to pay with the credit card, not cash. (TARJETA (DE CRÉDITO)) |

tarjeta (de crédito) - 121 carta de crédito - 1 N/A - 6 |

He bought a new camera to record his journey to America. (GRABAR, ESTADOS UNIDOS) |

grabar/EstadosUnidos - 12 hacerfotos/EstadosUnidos - 1 filmar/EstadosUnidos - 1 documentar/EstadosUnidos - 1 grabar/América - 87 llevar (registro)/América - 1 no verb/América - 4 recordar/América - 1 recoger/América - 1 filmar/América - 3 documentar/América - 1 registrar/América - 5 formar/América - 1 inmortalizar/América - 1 guardar/América - 1 N/A - 7 |

El ladrón hizo el crimen muy grave. (CORRECT) |

correct - 44 incorrect - 1 N/A - 5 rewritten in English correct - 63 rewritten in Spanish correct - 13 invalid answers - 2 |

La semana que viene iré al partido para soportar mi equipo favorito. (INCORRECT, APOYAR A) |

correct - 32 incorrect - 2 N/A - 4 rewritten in English correct - 61 rewritten in Spanish correct - 16 to cheer up - 3 to hold - 1 to endure - 1 to watch - 1 to encourage - 1 to see - 1 to stand - 1 animar a - 1 respaldar - 1 sostener - 1 invalid answers - 1 |

Estoy pensando en comprar la ropa nueva. (CORRECT) |

correct - 64 incorrect - 1 N/A - 4 rewritten in English correct - 47 rewritten in Spanish correct - 12 |

Envio mucho a esta chica polaca porque siempre viaja con su familia. (INCORRECT, ENVIDIAR A) |

correct - 22 incorrect - 5 N/A - 8 rewritten in English correct - 49 rewritten in Spanish correct - 20 rewritten in Spanish incorrect - 3 rewritten in English incorrect (to send) - 19 invalid answer - 2 |

The first three sentences that are taken from the task required rewriting the sentence in English only. As is shown in Table 5, the participants did well with the first two sentences, although they proposed an abundance of alternative words for the first sentence that in some cases, considering the context, could be also accepted as a synonym for the required word. The third sentence proved tricky, and the majority of respondents did not grasp that America was also a FF and concentrated more on the verb to record. On the one hand, because of that, the results for this entry were distorted. The results demonstrate that participants lost their alertness and did not realize that not all sentences were designed to have only one FF. Besides, it could be stated that they might not know the semantic difference of the word as it belongs to the semantic inclusion, meaning that in English America refers to the US, meanwhile in Spanish it refers to the whole continent.

The final exercise of the survey required participants to indicate whether the sentence is correct, and if not, rewrite it correctly in Spanish. For this commentary, the several highlighted answers were accepted as correct since some people just rewrote sentences correctly even though it was not necessary. A significant majority successfully dealt with the task. Taking everything into account, it could be declared that language learners can recognize false friends and handle this phenomenon well enough.

Conclusion

- The analysis of the selected English and Spanish word pairs resulted

in several major findings that completely refuted the expectations that

were raised before the research:

1.1. Firstly, the comparison of the distribution of the parts of speech in both languages revealed that the most dominant part of speech among false friends in English and Spanish is the category of nouns, meaning that the phenomenon of FFs has not influenced any changes in the traditional grammar.

1.2. Secondly, the French influx into the English language is higher than it was expected and has drastically changed the lexis of English vocabulary, which is reflected in the emergence of the phenomenon in the English language. Therefore, most of the FFs share the Latin origin, which means that this phenomenon has been transmitted in the English language easier and more naturally but not vice versa.

1.3. Finally, the most prevailing type of FFs is semantic total, meaning that the words have developed completely different meanings throughout time and there is very little chance that they can be translated by a speaker of the other language. Consequently, English-Spanish false friends express the highest degree of false friendship and the lowest degree of semantic resemblance.

- The results of the questionnaire affirmed that the majority of the L2 users are aware of such linguistic phenomenon, can recognize FF pairs and understand their meanings in English and Spanish, and in most cases avoid miscommunication by detecting the mistakes caused by them.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank our two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions, and Jeff La Roux for proofreading the English text. Needless to say, all possible errors and misinterpretations are ours.

List of abbreviations

DEC – Diccionario Etimológico Castellano

DRAE - Diccionario de la Real Academia Española

FF(s) – false friend(s)

L1 – the first language; mother tongue; native language, the source language.

L2 – the second language; the target language.

LT – language teaching

OE – Old English

OED - Online Etymology Dictionary

References

AL-ATHWARY, A. H., 2021. False friends and lexical borrowing: A linguistic analysis of false friends between English and Arabic. Journal of Language and Linguistic Studies, 17, 368–383.

ALVAREZ LUGRIS, A., 1997. Os falsos amigos da traducción: Criterios de estudio e clasificación. Vigo: Universidade de Vigo.

AL-WAHY, A. S., 2009. Idiomatic false friends in English and modern standard Arabic. Babel, 55(2), 101–123. https://doi.org/10.1075/babel.55.2.01wah

CHACÓN BELTRÁN, R., 2004-2005. The effects of focus on form in the teaching of Spanish-English false friends. RESLA 17-18, (2004-2005), 65–79.

CHACÓN BELTRÁN, R., 2006. Towards a typological classification of false friends (Spanish-English). RESLA, 19, 29–39.

CHAMIZO-DOMÍNGUEZ, P. J., & NERLICH, B., 2002. False friends: Their origin and semantics in some selected languages. Journal of Pragmatics, 34, 1833–1849.

CHAMIZO-DOMÍNGUEZ, P. J., 2008. Semantics and pragmatics of false friends. London/New York: Routledge.

CHAMIZO-DOMÍNGUEZ, P. J., 2009. Los falsos amigos desde la perspectiva de la teoría de conjuntos. Applied Linguistics Now: Understanding Language and Mind/La Lingüística Aplicada Actual: Comprendiendo el Lenguaje y la Mente. Universidad de Málaga, 1111–1126.

DURÁN ESCRIBANO, P., 2004. Exploring cognition processes in second language acquisition: The case of cognates and false-friends in EST. Universidad Politécnica de Madrid. IBÉRICA, 7, 87–106.

GALLOSO CAMACHO, M. V., & RENGEL CASIMIRO, A., 2021. Falsos amigos: divergencia semántica inglés - español de algunas formas poco estudiadas. Tonos digital, 40(0).

GOUWS, R. H., PRINSLOO, D. J., & SCHRYVER, G. M., 2004. Friends will be friends – true or false. Lexicographic approaches to the treatment of false friends. Proceedings of the 11th EURALEX International Congress. France: Universite de Bretagne, 797–806.

GRANGER, S., & SWALLOW, H., 1988. False friends: a kaleidoscope of translation difficulties. Language el I'Homme, 23, 108–120.

LENGELING, M. M., 1996. True friends and false friends, ED399821, 2–7. Available from: URL https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED399821.pdf

MENDILUCE CABRERA, G., & HERNANDEZ BARTOLOME, A. I., 2005. English / Spanish false friends: a semantic and etymological approach to some possible mistranslations. Hermēneus. Revista de Traduccion e Interpretación, 7, 131–157.

O'NEILL, M., & CATALÁ, M. C., 1997. False friends: a historical perspective and present implications for lexical acquisition 1. Bells: Barcelona English language and literature studies, 103–115.

PINAZO ENCARNACIÓN, P., 1996. Estudio contrastivo de los falsos amigos en inglés y en español. Doctoral Tesis (in microform). Málaga: Universidad de Málaga.

ROCA-VARELA, M. L., 2015. False friends in learner corpora: a corpus-based study of English false friends in the written and spoken production of Spanish learners. Bern, Switzerland: Peter Lang AG, International Academic Publishers.

SALES, S. I., 1998. False friends in English for Spanish-speaking students of English: morphology, syntax and lexis as sources of false friendship. Jornades de Foment de la Investigació, 4, 165–170.

SEICIUC, L., 2017. Three metalinguistic factors in linguistic change: Lexicosemantic relations, folk etymology and false friends. Meridian Critic, 28(1), 87–90.

SHEEN, R., 1997. English faux amis/false friends for francophones learning English. Volterre-Fr English and French Language Resources.

STANKEVIČIENĖ, L., 2002. English-Lithuanian lexical pseudo-equivalents. Kalbotyra, 52(3), 127–136. Available at: https://www.journals.vu.lt/kalbotyra/article/view/23337

VEISBERGS, A., 1996. False friends dictionaries: A tool for translators or learners or both. Proceedings of the Seventh EURALEX 1996 International Congress on Lexicography in Göteborg, 627–634.

Sources

Cambridge Advanced Learner’s Dictionary. Available at: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/

DEC - Diccionario Etimológico Castellano En Línea (2001). In etimologias.dechile.net dictionary. Available at: http://etimologias.dechile.net/

DRAE - Diccionario de la Real Academia Española. Available at: https://dle.rae.es/

The Free Dictionary. Available at: https://www.thefreedictionary.com/

WordReference online translation dictionary. Available at: https://www.wordreference.com/

Appendix 1

The list of the English-Spanish false friends word pairs used in the analysis. The word pairs are listed in alphabetic order.

A:

- Actually/actualmente

- (to) actuate/actuar

- Adept/adepto

- (to) adequate/adecuado

- (to) advertise/advertir

- (to) advise/avisar

- (to) affront/afrontar

- Allocated/alocado

- America/ámerica

- Ancient/anciano

- (to) approve/aprobar

- Argument/argumento

- (to) assume/asomarse

- (to) attend/atender

- Avocado/abogado

B:

- Bachelor/bachiller

- Bald/balde

- Balloon/balón

- Bank/banco

- Bigot/bigote

- Billion/billon

- Bizarre/bizarro

- Bland//blando

- Blank/blanco

- Body/boda

- Bomber /bombero

C:

- Camp/campo

- Candid/cándido

- Cargo/cargo

- Carpet/carpeta

- Card/carta

- Cask/casco

- Casually/casualmente

- Casualty/casualidad

- (to) choke/chocar

- City/cita

- Client/cliente

- Code/codo

- Collar/collar

- College/colegio

- Competence/competencia

- Comprehensive/comprensivo

- Conductor/conductor

- Constipated/constipado

- Contest/contestar

- Crime/crimen

- Curse/curso

D:

- Deception/decepción

- Delight/delito

- Desperate/despertar

- Destitute/desituido

- Disgust/disgusto

- (to) divert/divertir

- Domicile/domicilio

- Dormitory/dormitorio

E:

- Embarassed/embarazada

- (to) empress/empresa

- Envy/enviar

- Estimate/estimado

- Exit/éxito

F:

- Fabric/fábrica

- Familiar/familiar

- Fastidious/fastidioso

- Fatality/fatalidad

- Feast/fiesta

- Firm/firma

G:

- Grab/grabar

- Gracious/gracioso

- Grocery/grosería

H:

- History/historia

- Horn/horno

I:

- Idiom/idioma

- Indignant/indignante

- Introduce/introducir

J:

- Jubilation/jubilación

L:

- Large/largo

- Lecture/lectura

- Library/librería

M:

- Mantel/mantel

- Mascara/máscara

- Mayor/mayor

- Measure/mesura

- Media/media

- Molest/molestar

N:

- Nude/nudo

- Number/nombre

O:

- Once/once

P:

- Pan/pan

- Parade/parada

- Parent/pariente

- Pie/pie

- Plant/planta

- Preservative/preservativo

Q:

- Quiet/quieto

- (to) quit/quitar

R:

- (to) realise/realizar

- (to) record/recordar

- Red/red

- (to) refund/refundir

- Rope/ropa

S:

- Sane/sano

- Scholar/escolar

- Sensible/sensible

- Signatura/asignatura

- Soap/sopa

- Spade/espada

- (to) stretch/estrechar

- Success/suceso

- (to) support/soportar

T:

- Topic/tópico

- (to) transcend/trascender

- (to) translate/trasladarse

- Tuna/tuna

U:

- Ultimately/últimamente

V:

115. Vase/vaso