Vertimo studijos eISSN 2029-7033

2019, vol. 12, pp. 87–98 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/VertStud.2019.6

Translation as Metaphor, the Translator as Anthropologist

Bruno Osimo

Civica Scuola Interpreti

e Traduttori «Altiero Spinelli»

Milano, Italy

b.osimo@fondazionemilano.eu

Abstract. The presence/absence of the notion of “inner language” in different cultures creates a watershed between various cultures as far as the notion of “translation” is concerned. Intersemiosity is seen, accordingly, as inner or outer process to interlingual translation. This gap is reflected in the metaphors attached to translation. By analysing them, the author gets a picture of the cultural roots of the view of translation in each culture. Anthropology can be a precious ally in the reciprocal definition of “translation” and “culture”. A new trope for translation is suggested: metaphor.

Keywords: anthropologist, intersemiosity, metaphor, translation

Vertimas kaip metafora, vertėjas kaip antropologas

Santrauka. Kalbant apie sąvoką „vertimas“ labai svarbi sąvoka „vidinė kalba“. Jos buvimas ar nebuvimas skirtingose kultūrose sukuria atskirtį verčiant įvairioms kultūroms atstovaujančius tekstus. Atitinkamai tarpsemiotiškumas vertinamas kaip vidinis ar išorinis tarpkalbinio vertimo procesas. Šis atotrūkis atsispindi vertimo metaforose. Jas analizuodamas straipsnio autorius daro išvadą, kad požiūris į vertimą kiekvienoje kultūroje grindžiamas toje kultūroje egzistuojančiais sąvokos „vertimas“ stereotipais. Antropologija gali būti vertinga sąjungininkė abipusiškai apibrėžiant „vertimą“ ir „kultūrą“. Siūlomas naujas vertimo tropas – metafora.

Pagrindiniai žodžiai: antropologas, metafora, tarpsemiotiškumas, vertimas

Copyright © 2019 Bruno Oisimo. Published by Vilnius University Press

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

Jakobson’s article “On Linguistic Aspects of Translation” in Brower’s collection by Oxford University Press (1959) containing the word “linguistic” in its title was tricky because, in time, that adjective has grown to have a completely different sense. If “linguistic” in 1959 meant “made of words” as opposed to “made of literature”, today it may sound as “lexical” as opposed to “semiotic”. Its title now might be “On semiotic aspects of translation”: it was potentially suggestive of an entirely new view of translation, based on the fact that the verbalization/deverbalization phases of the process could be considered, in fact, to be intersemiotic translations. But the presence or absence of the notion of “inner language” in different national education systems has created a watershed between various cultures as far as the notion of “translation” is concerned. In countries where the notion of “inner language” is not widespread among translation researchers, the connection between Jakobson’s premises and the matching translation view was not fully caught. Where inner language is unknown or, at most, overlooked, intersemiosity is seen, accordingly, as outer to the interlingual translation process. Intersemiotic translation is then seen in processes like films inspired by novels, pictures inspired by poems, buildings inspired by worldviews, and so on. This gap among academic nations is reflected in the metaphors attached to translation. By analysing them, we get a picture of the cultural roots of the view of translation in each culture. Anthropology can be a precious ally in the reciprocal definition of “translation” and “culture”. A new trope for translation is suggested: metaphor itself.

1. The linguistic fallacy

The often quoted 1959 paper by Jakobson “On linguistic aspects of translation” could have been a revolution in Translation Studies – as they were called at the time, translation theory – it could have caused an explosion in the Lotmanian (1992) sense of the word, pushing researchers towards a “semiotic approach to translation”, to quote Ludskanov’s famous 1975 article.

None of the above occurred. Jakobson’s paper was implicitly based on Vygotsky’s notion of “inner language”, and when he stated that there are interlingual, intralingual, and intersemiotic translations, he took for granted that the three of them occurred in the ‘simple’ translation process, as input/output from/into the continuous language of the mind and the discrete language of the word.

In the West, however, Vygotsky’s inner language is seldom considered by translation scholars. This notion is not taught in high schools, and at university courses you find it exclusively at pedagogy and psychology faculties. For example, out of 97 scientific papers found (GoogleScholar 2019) with a specific keyword combination in Italian («Vygotsky “linguaggio interno”»), 75 are by pedagogists or psychologists, and none is about translation (but for the ones by the author of the present paper).

For this reason, in the West the notion of “intersemiotic translation” introduced by Jakobson 1959 was received as an impulse to think of films being made from novels, pictures from poems, and so on, but it was not applied to translation proper, to the relationship between discrete (verbal) language and continuous (mental) language within the translator’s mind. For this reason, translation theory remained tied to notions like equivalence, literality, faithfulness, and so on (Osimo 2011). When one acquires notions that help explain a process, the mental model that one builds oneself is based on these notions. For this reason, I think that the metaphors used for a given phenomenon can be used as a window on the mental model consciously or unconsciously used by someone to work on a notion. I will start by analyzing the main metaphors of translation, as metaphors are the collective unconscious of any culture (Burke 1992; Dwairy 2015).

2. Translation Metaphors we Live by

There has been a gap between translation and academy. Translation (as an activity) and academy (as research) have long proceeded along parallel paths. Westerners generally – as a collective culture – tend to ignore translation as a subject on its own. In most countries there are few university faculties of translation; there are, rather, philology faculties and/or language faculties. Significantly, the oldest and most famous translation schools in the world were born as non-university schools, as professional schools. Geneva’s, for example, was founded in 1941, by Antoine Velleman, as the École d’interprètes de Genève (EIG) (Stelling-Michaud 1959). Trieste’s was founded in 1962 as “Scuola a fini speciali di Lingue Moderne per Traduttori ed Interpreti di Conferenze”. Since it is clear now that translation is a process (Sütiste, Torop 2007), maybe it is difficult to consider it as a subject. For this point of view, both semiotics and translation perhaps share the same destiny. They both refer to processes, not objects, and tend to be overlooked by Western research. Many metaphors were attached to translation in history. None of them used to consider it as a process, though.

2.1 The wrong trope of translation as path

One of the most widespread implicit metaphors is translation as a path. When you say “target text” “source text” or, in Italian, “testo di partenza”, “testo d’arrivo”, you are implying that translation is a trip. The translator is, in this implicit view, a mover, which in turn implies that there are ‘objects’ to be transferred in space, but they remain the same, only change geographical location. This, in turn, implies that the translator has no creativity, she is simply told where she has to move the ‘object’.

But since we, by contrast, consider cultures as living organisms, not places, and the process of adapting a text to a culture as creative, and as one producing changes in both the transmitting culture and the receiving culture, we cannot accept this metaphor. In our opinion, the text is not an object. It is a process, starting in the author’s mind and ending in the reader’s mind (Torop 2010:115).

2.2. The wrong trope of translation as copy

Since the notion of ‘equivalence’ is often used when speaking of translation, people tend to think of translation in terms of a copy. But interpretation is always involved in the identification of the sense(s) to be actualized in every case, and interpretation is incompatible with equivalence, because it is the individual’s response to a given text projected onto a given culture.

If you conceive of reading in terms of the Peircean triad sign-interpretant-object, the text being read is the sign, the result of the reading is the object, and in between each reader/translator interprets in their own way the text. Therefore, there is no copy, no equivalence, only subjective correspondence.

If it weren’t so, machine translation would have worked fine, and back translation would (re)generate the prototext. As we all know perfectly well, back translation generates a third text, which is different from the prototext (Lotman 1992:161).

The translator is not a copyist. Even copyists produced metatext often unwillingly different from their originals. Translators, however, do not have the copy even as target. Their aim is to make a different text, useful to produce a similar sense in a different culture. While a copy is identical to the original, a translation has, in principle, part of the sense that is – willingly or unwillingly – added by the translator, and part of the sense that is lost, a residue.

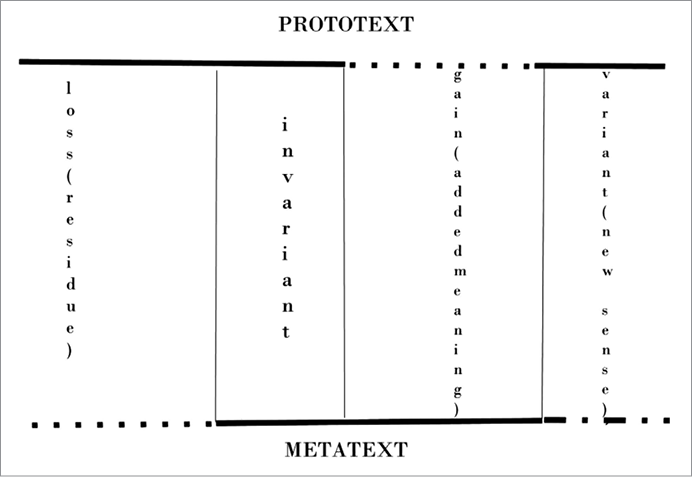

Figure 1. The translation process (by Bruno Osimo)

The translator has a style of her own, the translator uses her creativity to make interpretative choices about the prototext, she produces something different. Lotman stated this principle, and used it as an example of how communication works at a general level:

What is even closer to the real message circulation process is the case when in front of the transmitter there is not one code, but a multiple space of codes k1, k2, ..., kn, each of which is a complex hierarchical device and allows the generation of a set of texts that are equally corresponding to it. The scheme of artistic translation shows that the sender and the receiver use different codes, K1 and K2, that partially overlap, but are not identical. In the case of back translation, the product will not give the original, but a third text T3. (Lotman 1996: 16)

Therefore, accepting Lotman’s point of view, it is impossible to see translation as a copy. We refuse the metaphor of translation as a copy because we know that translation is a creative process.

2.3. The wrong trope of translation as challenge

One of the most widespread tropes is the one according to which the translator must face the challenge of not letting the reader know that there has been a mediation work to prepare the text being read. This is the principle of giving the illusion of the original. Why can’t the trope of translation as challenge work?

This view is based on the assumption that the reader must not know the truth (the translation work) and/or cannot understand that there has been one. If the translator makes a footnote, for example, the challenge is automatically lost. The situation in which this principle is most obvious is dubbing. Dubbers are allowed (have the duty) to distort the reality of the message (sense) to adapt it to the fraud of the metatext passed off as a prototext. And the more they are good at it, the more they are able (finding words that produce the same labial movements as the original), the more they falsify the text.

This is a case of psychosis applied to translation: denial of the original, pretending that it didn’t exist, that the film was written in the language of the receiving culture. The aim of this strategy is to induce delusions in the receiving culture.

The overall view implicit in this translation approach is that of the translator as an avant garde, and the readers as “Little People” who need the avant garde intervention to decipher texts. Vladimir Nabokov had clear-cut ideas on the subject:

[the translator] will tone down everything that might seem unfamiliar to the meek and imbecile reader visualised by his publisher. But the honest translator is faced with a different task. In the first place, we must dismiss, once and for all, the conventional notion that a translation “should read smoothly”, and “should not sound like a translation” (to quote the would-be compliments, addressed to vague versions, by genteel reviewers who never have and never will read the original texts). In point of fact, any translation that does not sound like a translation is bound to be inexact upon inspection; while, on the other hand, the only virtue of a good translation is faithfulness and completeness. Whether it reads smoothly or not depends on the model, not on the mimic. (Nabókov 1959: xii-xiii)

The “honest translator” does not think that her readers are imbeciles. Readers do understand, that is the reason why they read. For this reason, the translator’s mediation should be strictly cultural, not cognitive (Osimo 2017). Unless the customer has explicitly asked for a simplification of the text – for example when the prototext is a scientific paper and the metatext is a popular science story in a newspaper – there should never be the – even unconscious – thought that, since they supposedly cannot understand something, it’s better to simplify or explain.

Any reader is able to cope with the fact that the text is a translation, not an original. In this case, too, the mediation action should be strictly cultural, not cognitive. So there must not be any attempt to pass the text for an original, otherwise the reader would feel taken for a ride. The reader, finding a translator’s note, is not desperate. If she is not interested in it, she might skip it (Osimo, Bartesaghi, Zecca 2013). While if she feels that reality has been manipulated by the mediator (as in the case of dubbed films with perfect lip sync), she feels cheated.

2.4. The wrong trope of translation as a transparent bridge

Everywhere (Cheng 2019, Dias-Cintas 2019, Do Amaral 2019, Xhillari 2019) you can find the stereotype that the translator would be a bridge between languages or cultures. This makes a technical structure of the translator, an object that, once it is built, functions for the passage of information between two places that, apparently, have a rift between them. Moreover, since that view takes for granted that the metatext must be perceived as a prototext (“the translation should read like an original”), in this inappropriate view this bridge should be transparent.

The most unrealistic feature of this view is that the translator would be a dead object. Not only the translator is alive, but according to Peeter Torop the text also is alive, being a process:

The text is a process that takes place between the consciousness of those who created it and the consciousness of the recipients; in other words, the beginning and the ending of this process are hidden in the human psiche. (Torop 2010: 115)

The translator cannot be a bridge because she thinks, and judges. The perception of the prototext alone is an operation involving the so-called hermeneutic circle (Gadamer 1975), in which the translator has a double responsibility of decoding for herself and decoding for her readers. Such an operation is highly creative because it involves a continuous choice between possible senses to be actualized in the metatext.

Moreover, any translator inevitably has her own style, that will merge with the prototext author’s style, creating a sort of creole style in the metatext. If she were a bridge, her task would be to transcribe the original. It would be like a duct between two containers. Again, the metaphor is that of culture as a homogeneous liquid and the translator as a sort of plumber. The point is that culture is a heterogeneous living structure. And there is a culture also within the translator herself. Translation, therefore, is an interaction of three cultures: the transmitting one, the receiving one and the translator’s.

While the prototext author translates her ideas (plot, message, sense, need to express, etc.) into a text, the metatext author (translator) translates the prototext author’s text into a text for the receiving culture, trying to guess the prototext author’s ideas that generated the prototext. They are both authors, with the difference that the prototext author has a wider choice of ideas to start with her writing project. In both cases there is an intersemiotic translation. For the prototext author, from her (mental) ideas into words, for the metatext author, from her (mental) representations of the prototext author’s text into a new text able to function in the receiving culture (Osimo 2009).

In these conditions a situation of [partial; ed.] untranslatability arises; however, it is precisely here that attempts to translate get accomplished with particular conviction and give the most precious results. In this case there is not an exact translation, but an approximate correspondence conditioned by that cultural-semiotic and psychological context shared by the two systems. A couple of significant elements reciprocally incomparable, between which, in a given context, a relation of adequacy exists, form a semantic trope. (Lotman 1990: 178)

More than this, the translator’s role is that of generating sense. According to Lotman, the only way to create sense is to have a relationship between two cultures, two languages, that are partially reciprocally untranslatable:

In individual and collective conscience two types of text generators are hidden: one based on the mechanism of discreteness, the other one continuous. [...] between them a constant exchange of texts and messages occurs. Such exchange happens in the form of semantic translation. However, any exact translation presupposes that between the units of the two systems two-way interrelations occur, that the representation of a system in the other one is possible. Which allows to adequately express the text in one language through the means of the other one. (Lotman 1990: 178)

Having discarded all the mentioned tropes traditionally connected to translation, we now need to find a new trope for translation, useful to understand it and not to create false ideas.

3. Translation as metaphor

It would not make sense to emphasize the tropes that in our cultures are more often used to speak about translation, and to assess their greater or smaller fitness to their object, without pointing to possible solutions, i.e. to possible tropes that would work well with translation. In 1989 Gregory Rabassa suggested that translation may be considered as a metaphor:

A word is nothing but a metaphor for an object or, in some cases, for another word (Rabassa 1989:1). [T]ranslation is what we might call transformation. It is a form of adaptation, making the new metaphor fit the original metaphor. (Rabassa 1989: 2)

The adoption of metaphor (sic) as a metaphor (sic) for translation would solve some problems. If we look up the definition of ‘metaphor’ in the dictionary, we find that it is “a word or phrase is applied to an object or action to which it is not literally applicable” (Stevenson, Lindberg 2005-2018). This, if applied to the notion of “translatant”, would mean that the translatant is applied (by the translator) to a word of phrase of the prototext, and that this application is not literal, all conditions that contradict the notion of equivalence but fit well with the notion of subjective correspondence.

The second definition of ‘metaphor’ is “a thing regarded as representative or symbolic of something else, especially something abstract” (Stevenson, Lindberg 2005-2018), which is also fit for the definition of translation: the metatext is a symbolic representation of the prototext and, as such, the point of view is that of the translator.

Lotman (1981:17) says that

not an exact translation, but an approximate correspondence comes into existence, conditioned by a certain cultural-psychological and semiotic context shared by both systems. Such irregular and inexact, yet, in a sense, correspondent translation is one of the essential elements of any creative thinking. Precisely these “irregular” convergences provide the impetus for the emergence of new sense relations and on principle new texts.

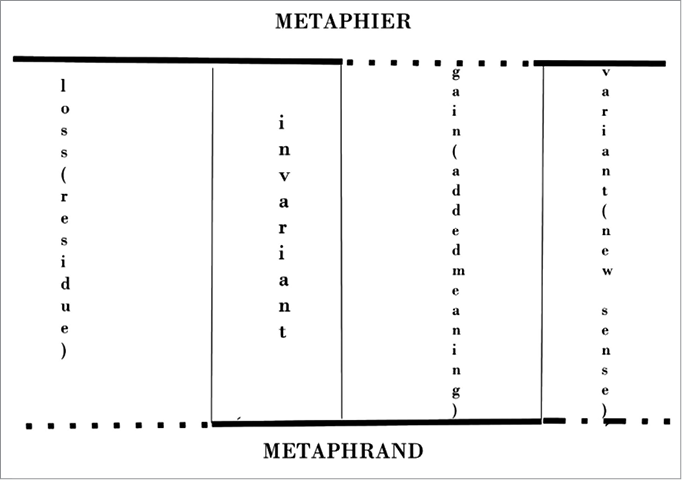

If translation is one of the essential elements of any creative thinking, then translation is a process involving all people – not translators only. Translators are the ones that apply such activity to the professional interlingual rewriting of texts. I introduce below the model of the metaphor process, with a scheme similar to the one used before for the translation process.

Figure 2. The metaphor process (by Bruno Osimo)

Metaphor has a variant and an invariant component; metaphor channels sense in a direction; metaphor as well alters sense without showing. In metaphor the metaphrand is not equivalent to the metaphier and there is no bi-univocal correspondence between the two. If you try to “backtranslate” the metaphier you don’t get the former metaphrand (Lotman 1996:178-187).

4. Culture as translation

If metaphors are a way to refer to something that is hardly expressible in a more direct denotative way, it may be useful to see the notion of ‘rich point’ that was introduced in anthropology by Michael Agar:

Rich points are those surprises, those departures from an outsider’s expectations that signal a difference between languaculture 1 and languaculture 2 and give direction to subsequent learning. (Agar 2006)

In terms of interlingual translation, rich points may be untranslatable words, untranslatable sentences, untranslatable notions. The translator, like the anthropologists, visits an alien culture and tries to explain it to members of her own culture. She tries to translate it in understandable terms.

Culture is the ethnographic product, the result that is a translation that links the languaculture 1 and the languaculture 2 that defined the ethnographic encounter in the first place. The simple answer, then, is to let culture label that translation. (Agar 2006)

It is very useful what Agar says about the relational variability of translations. One cannot say “This is THE translation of this text”:

Like a translation, culture is relational. Like a translation, culture links a source languaculture, languaculture 2, to a target languaculture, languaculture 1. Like a translation, it makes no sense to talk about the culture of X without saying the culture of X for Y. (Agar 2006)

One can say at most that “This is the translation of this text from the point of view of the Y translator”. It is therefore natural the existence of as many versions of classic books as many translators engaged in their translation.

Culture, then, is first of all a working assumption, an assumption that a translation is both necessary and possible to make sense of rich points. (Agar 2006)

Rich points, i.e. untranslatability, are seen as factors of learning, of mutual enrichment of cultures. This perspective can prove interesting for translation as well. The translator faced with something untranslatable, in this view, is not in anguish; on the contrary, she is experiencing enrichment of her culture, and from this consideration moves on to envisage the way to communicate her view of the alien culture to her own culture members.

5. Translation as culture

In Lotman’s view, there can be no dynamic cultural system if there are not at least two mutually untranslatable languacultures:

Related to this is the property of culture, which can be described as principled polyglotism. No culture can be satisfied with one language only. The least system is formed by a set of two parallel languages – e.g., verbal and visual. (Lotman 1977: 563)

This is another way to say what Agar thought about culture: culture is a translation. Culture cannot be alone, and cultural identity is possible only if there is another different culture that confronts it.

The mutual intersection of semiotic systems inadequate to each other, and only intertranslatable within any semiotic unity, is the basis of the dynamics of semiotic structures. (Lotman 1994: 105)

Translation is what, in a culture, gives sense to existence. Without translation culture would be static.

An element of the prototext can be matched by a set of elements, and vice versa. Matchmaking always implies a choice, is fraught with difficulties, and has the nature of discovery, of enlightenment. It is such a translation of the untranslatable that is the mechanism for creating new sense. It is based not on mono-sign transformation, but on an approximate model, on analogy, metaphor. (Lotman 1977: 13)

For the anthropologist, for the semiotician, for the translator alike, translation is culture, and specifically it is culture of the border.

Similar to how in mathematics the border is a set of points that belong simultaneously to the interior and the exterior, the semiotic border is a set of bilinguistic translational ‘filters’, the passage through which translates text into another language (or other languages) that resides outside of the given semiosphere. (Lotman 1981: 13)

Conclusions

Translation studies must free themselves of all the old, inappropriate metaphors associated with the word “translation”. Translation itself is a metaphor, and it is a central notion both in anthropology and in semiotics. To emancipate translation from its ancient role as Cinderella of linguistics and humanistic studies, it is necessary to re-evaluate translation studies by drawing on anthropology and semiotics, where “translation” is the key notion to define the concept of “culture” itself.

References

Agar, Michael. 2006. Culture: Can You Take It Anywhere? Invited Lecture Presented at the Gevirtz Graduate School of Education, University of California at Santa Barbara. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 5 (2) June. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500201.

Burke, W. Warner. 1992. Metaphors to consult by. Group & Organization Management, 17. 255–259.

Cheng, Chen, Wang Xuecheng and Chen Fei. 2019. Countermeasures of National Culture in the Context of Cultural Globalization. 5th International Conference on Social Science and Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.2991/icsshe-19.2019.197.

Díaz-Cintas, José. 2019. Audiovisual Translation in Mercurial Mediascapes. Advances in Empirical Translation Studies. Cambridge: CUP. 177–197. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108525695.010.

do Amaral, Vitor Alevato. 2019. Ampliando a noção de retradução. Cadernos de tradução, 39 (1). 239–259. https://doi.org/10.5007/2175-7968.2019v39n1p239.

Dwairy, Marwan. 2015. Using Metaphors in Culture Analysis. From Psycho-Analysis to Culture-Analysis. Palgrave Macmillan, London. 42–61. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137407931_5.

Gadamer, Hans-Georg. 1975. Hermeneutics and Social Science. Philosophy Social Criticism / Cultural Hermeneutics. 2 (4). 307–316. https://doi.org/10.1177/019145377500200402.

Google Scholar 2019. Search key: «Vygotskij “linguaggio interno”», accessed November 2019. https://scholar.google.com/scholar?start=60&q=vygotskij+%22linguaggio+interno%22&hl=en&as_sdt=0,5.

Jakobson, Roman. 1959. On Linguistic Aspects of Translation. On Translation, edited by Reuben Arthur Brower. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Lotman, Jurij. 1977. Kul’tura kak kollektivnyj intellekt i problemy iskusstvennogo razuma. Nauchnyj sovet po kompleksnoj probleme «Kibernetika». Moskvà: Akademiya Nauk SSSR.

Lotman, Jurij. 1981. Mozg–tekst–kul’tura–iskusstvennyj intellekt. Semiotika i informatika. Moskvà. 1. 13–17.

Lotman, Yuri. 1990. Universe of the mind: a semiotic theory of culture. Translated by Ann Shukman; introduction by Umberto Eco. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Lotman, Jurij. 1992. Kul’tura i vzryv. Moskvà: Gnosis.

Lotman, Jurij. 1996. Vnutri myslyaschih mirov: Chelovek–Tekst–Semiosfera–Istoriya. Moskvà: Yazyki russkoj kul’tury.

Ludskanov, Alexander. 1975. A semiotic approach to the theory of translation. Language Sciences, April. 5–8.

Nabokov, Vladimir. 1959. The servile path. On Translation, edited by Reuben Arthur Brower. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. 97–110.

Osimo, Bruno. 2009. Jakobson and the mental phases of translation. Mutatis Mutandis, 2(1), 73–84.

Osimo, Bruno. 2011. Dynamics of Basic Terminology in Translation Science between “East” and “West”. Acta Universitatis Carolinae Philologica 2. 103–113. Univerzita Karlova v Praze: Nakladatelství Karolinum.

Osimo, Bruno, Federica Bartesaghi, and Silvia Zecca. 2013. La nota del traduttore. Un sondaggio. Testo a fronte 47.

Osimo, Sofia Adelaide and Bruno Osimo. 2017. Cognitive distortion, translation distortion and poetic distortion as semiotic shifts. Ars Aeterna, 9 (2). 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1515/aa-2017-0006.

Rabassa, Gregory. 1989. No two snowflakes are alike: translation as metaphor. The Craft of Translation, edited by John Biguenet and Rainer Schulte, Chicago/London: The University of Chicago Press.

Stelling-Michaud, Sven. 1959. L’École d‘interprètes de 1941 à 1956. Histoire de l’Université de Genève, Georg, 317.

Stevenson, Angus, and Christine Lindberg (eds). 2005-2018. New Oxford American Dictionary. Oxford. Oxford University Press.

Sütiste, Elin, and Peeter Torop. 2007. Processual boundaries of translation: Semiotics and translation studies. Semiotica 163. 187–207. https://doi.org/10.1515/sem.2007.011.

Torop, Peeter. 2010. La traduzione totale: tipi di processo traduttivo nella cultura, edited by Bruno Osimo, Milano: Hoepli. https://doi.org/10.5007/2175-7968.2010v1n25p228.

Vygotsky, Lev S. 1934. Myshlenie i rech´. Psihologicheskie issledovaniya, Moskvà–Leningrad: Gosudarstvennoe Sotsial´no–Èkonomicheskoe Izdatel´stvo.

Xhillari, Rudina. 2019. Englishing of Ismail Kadare’s “The Siege” as an indirect translation. Uluslararası Afro-Avrasya Araştırmaları Dergisi, 4 (7). 221–229. https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/ijar/issue/43278/504811