Vertimo studijos eISSN 2029-7033

2019, vol. 12, pp. 150–164 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/VertStud.2019.10

On Optional Shifts in Translation from Persian into English

Helia Vaezian, Fatemeh Ghaderi Bafti

KHATAM University

Tehran, Iran

vaezian.Helia@gmail.com

samira.gh90@yahoo.com

Abstract. Some changes always take place in the process of transferring the meaning embedded in the source text into the target text. The present paper aims at investigating the formal dissimilarities between the source and target texts through the examination of all optional shifts made at word, phrase and clause/sentence levels. To this end, Pekkanen’s (2010) model was applied to the English translation of a Persian novel ‘Journey to Heading 270 Degrees’ into English. Optional shifts were identified and analyzed through a comparative linguistic analysis between the source and target texts. 926 instances of optional shifts were identified in translation of the novel into English, amongst which shifts of expansion-addition (203 instances) were the most dominant type. Moreover, it was revealed that optional shifts at a clause/sentence level with a total of 554 instances were more frequent than optional shifts at a phrase level (161instances) and word level (220 instances).

Keywords: optional shift, expansion-addition shift, clause/sentence level

Apie pasirenkamuosius pakeitimus verčiant iš persų kalbos į anglų kalbą

Santrauka. Stengiantis perteikti verčiamo teksto prasmę iš vienos kalbos į kitą neišvengiamai daromi tam tikri pakeitimai. Šiame straipsnyje tiriami visi pasirenkamieji pakeitimai, padaryti žodžio, žodžių junginio ir sakinio lygmenyje, siekiant nustatyti formalius išversto teksto ir originalo skirtumus. Šiuo tikslu vertimo į anglų kalbą analizei buvo pritaikytas Pekkaneno (2010) modelis. Tyrimo objektas – persų kalba parašyto romano „Journey to Heading 270 Degrees“ vertimas į anglų kalbą. Tyrimo metodas – gretinamoji lingvistinė analizė. Vertime buvo nustatyti 926 pasirenkamųjų pakeitimų atvejai, tarp kurių dažniausiai pasitaikė pridėjimas (eksplikavimas) – 203 atvejai. Be to, nustatyta, kad pasirenkamieji pakeitimai sakinio lygmenyje yra gerokai dažnesni (iš viso 554 atvejai) negu žodžio (220 atvejų) ar žodžių junginio lygmenyje (161 atvejis).

Pagrindiniai žodžiai: pasirenkamieji pakeitimai, pridėjimas, eksplikavimas, žodžių junginio lygmens pakeitimai, sakinio lygmens pakeitimai

Copyright © 2019 Helia Vaezian, Fatemeh Ghaderi Bafti. Published by Vilnius University Press

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

1. Introduction

How the source text is translated into the target language has been a constant concern in Translation Studies engaging translation scholars for years. To explore into this issue, they may observe what translators do to better understand the translation process or they may analyze the translated texts to come up with the changes that occur during the process of translation. The dissimilarity observed between the source and target texts has been referred to by many scholars using various terms. For instance, Larson (1984) used the term skewing, while Vinay and Darbelnet (1991) refer to it as transposition, and Catford (1965) talked of shifts. The concept of shift though mainly associated with Catford (1965), has been dealt with by scholars like Leuven-Zwart (1989), Popoviĉ (1970), Toury (1995), Klaudy (2003), Chesterman (2004), and so many others. Catford (1965: 27) defines shift “as the fairly straightforward, even inevitable, result of deviating from formal equivalence”.

Shifts in translation can be divided into various classifications. For instance, Catford’s (1965: 141) classification of shifts consists of two levels, level shift and category shift. Level shift “occurs with shift from grammar to lexis and vice versa”, while category shift means “change from the formal correspondence in translation, furthermore, it is divided into structure shift, class shift, unit shift, and intra shift”. On the other hand, there is another classification of shifts including, optional shifts, obligatory (mandatory) shifts, and non-shifts defined by many translation scholars. Al-Qinai (2009: 23) concerning this classification, claims:

Mandatory shifts result from a systematic dissimilarity between the source language and the target language in terms of the underlying system of syntax, semantics and rhetorical patterns...On the other hand, optional shifts are carried out by the translator’s personal preferences under the influence of idiolect and level of proficiency in the target language.

In line with the same discussion, Al-Qinai (2009: 25)states that using obligatory shift or optional shift depends on the translator’s perception to determine which shift is linguistic and which one is non-linguistic. According to him, sometimes optional shifts take place to meet commissioner’s needs and target audience’s expectations. He believes “many cases of explicitation, implicitation, omission and substitution” happen because of the commissioner’s request or the translator’s own preference in order to adapt the translation with “age, education and cultural background of the target audience”. However, he asserts that non-shifts happen “when source elements (e.g. sentence, clause, phrase, word, image or metaphor) are reproduced intact into the target language”.

Furthermore, Farahzad (2012: 39–40) distinguishing between obligatory shifts and optional shifts, states, “obligatory shifts are due to lack of correspondence between the linguistic systems of the protolanguage and the metalanguage. Optional shifts are due to translator’s choice and may have various reasons behind them, such as stylistic, cultural, or ideological”.

Eventually, Pekkanen (2010: 42) claims that “shifting is seen merely as the existence of formal dissimilarities between the source and target texts”. She distinguishes among non-shifts, as the situation in which “no shift takes place” (2010: 37), obligatory shifts, which occur mostly due to a linguistic or cultural force, and optional shifts, which “take place without any linguistic or cultural necessity” (2010: 38).

Drawing on Pekkanen’s (2010) model, the present study explores into optional shifts thorough a linguistic comparative analysis of the Persian novel ‘Journey to Heading 270 Degrees’, a well-known novel on Iran-Iraq War written by 1Ahmad Dehghan, and its translation into English by Paul Sprachman. The English translation contains 264 pages and was published by Mazda Publication in 2006.

2. Methodology

Since the purpose of the present paper was to investigate into the shifts made optionally by the translator in the English version of the novel ‘Journey to Heading 270 Degrees’, Pekkanen’s (2010) model adopted from Leech and Short (1981) was used.

2.1. Unit of translation analysis

Following Glaser and Strauss’s grounded theory (1967) adopted by Pekkanen (2010), the analysis of optional shifts in this study was done at a word, phrase and clause/sentence levels. Table 1 shows the levels of the optional shift analysis in this study.

As Pekkanen (2010: 61) states, “words, phrases and clauses/sentences are described in terms of absence or presence, any formal changes made to them and their place in the text”. Among this classification, distinguishing phrases and clauses might be a little confusing. In this regard, Pekkanen (2010: 61) provides a definition for phrase and claims that “the term ‘phrase’ is used for groups consisting of more than one word, for instance a headword and a qualifier or a non-finite verb and its object, and covers all groups that are not full (i.e. finite) clauses”. Moreover, Haiman and Thompson (1988: 3) provide a definition for clause and state, “one way of look at clauses is in terms of their constituency: a clause is a segment of language that consists of a subject and a predicate”.

Table 1. Levels of the Optional Shift Analysis

|

Word level: Single words

|

Phrase level: All word combinations that are not finite clauses |

Clause/sentence level: Finite clauses and sentences |

|

- deleted - added - changed - place |

- deleted - added - changed - place |

- deleted - added - changed - place |

2.2. Data Analysis

Optional shifts in this study were identified through a comparative linguistic analysis of the source and the target texts using Pekkanen’s (2010: 38) definition of optional shifts. Pekkanen (2010) believes that “optional shifts… may take place without any linguistic or cultural necessity. It is optional shifts like these that allow translators the freedom of choice and are thus the most likely to reflect their individual propensities”. In order to clarify the statement an example is provided in the table below.

Table 2. Instances of Optional Shift

|

Source Segment in Persian |

16 |

|

Source Segment in Latin |

mādar xoreŝt e Qormesabzi rā mikeŝad migozārad vasat e sofreh. (p. 16) |

|

Word for word translation |

mother places a bowl of Qormesabzi on the tablecloth-(p. 29) |

|

Target Segment |

mother places a bowl of stew made with greens on the tablecloth-(p. 29) |

Table 3. Instances of Optional Shift

|

Source Segment in Persian |

19 |

|

Source Segment in Latin |

Sofreh pahn ŝodeh va mādar kāseie Ăbgoŝt rā dor e sofreh micinad. (p. 19) |

|

Word for word translation |

The cloth is spread out and mother is passing a bowl of abgosht around- (p. 33) |

|

Target Segment |

The cloth is spread out and mother is passing a bowl of abgosht around- (p. 33) |

In the examples noted in Table 2, the translator uses optional expansion-replacement shift by expanding the sentence and replacing it with a longer one, without adding any new information. This kind of shift is optional because the translator in another case transliterates the Persian word “Ăbgoŝt” as italicized “abgosht”, without any expansion, while for the Persian word “Qormesabzi” he uses expansion-addition (see Table 3). Therefore, although the above-mentioned Persian words both are culture-bound elements, the translator had the option to either expand them or transliterate them. It is necessary to mention that the reasons behind the translator’s inclination towards using certain strategy were not the focus of the present study.

Pekkanen’s (2010) model investigates these formal optional shifts in each translation through four factors including expansion, contraction, order, and miscellaneous shifts. These factors are further broken down into some sub-factors including expansion-addition and expansion-replacement, contraction-deletion and contraction-replacement, order of time, order of place, and order of other types of shifts, and the miscellaneous shifts consisting of tense, modality, dixies, singular to plural, plural to singular, active to passive, passive to active, agency, deletion of repetition, etc. (more detailed explanations are presented below).

• Expansion

Expansion in this study covered both “replacement of a unit with a longer one (using more words than in the equivalent source text unit) without actually adding any information content that was not present in the source text” (Pekkanen 2010: 81), and the addition of extra “linguistic elements”. This usually also involves addition of some new information that the added element carries, which indicates an eventual semantic shift, too” (Pekkanen 2010: 73). Instances are provided for each one.

Table 4. Instance of Expansion-Addition Shift

|

Source Segment in Persian |

– |

|

Source Segment in Latin |

– |

|

Word for word translation |

– |

|

Target Segment |

From the alleys farther on, some boys rush toward us, with stones in their hands- (p. 49) |

|

Unit of Analysis |

Clause/sentence level: Finite clauses and sentences |

Table 5. Instance of Expansion-Replacement Shift

|

Source Segment in Persian |

52 |

|

Source Segment in Latin |

Tu tim e xodemon mikeŝimet ta biay. (p. 52) |

|

Word for word translation |

we’ll put you on our side until you come back- (p. 70) |

|

Target Segment |

I’ll put you on our side and we’ll play without you until you come back- (p. 70) |

|

Unit of Analysis |

Clause/sentence level: Finite clauses and sentences |

In the example provided in Table 4, a sentence in the source text is expanded in the target text through the addition of extra linguistic elements and new information for the target readers. However, in the second example in Table 5, the sentence in the source text has been replaced with a longer sentence in the target text, but the translation does not provide any new information for the target readers.

• Contraction

Contraction shift analysis in this research covered both “shifts involving contraction through replacement of a source text unit by a shorter one (i.e. one applying fewer words) in the target text, but without leaving out any content elements” (Pekkanen, 2010: 85), and “contraction through deletion of a unit in the source text (sentence, clause, phrase or word). The latter may involve deletion of information content”.

Table 6. Instance of Contraction-Deletion Shift

|

Source Segment in Persian |

|

|

Source Segment in Latin |

Rasool mesl e gorbeh ie balaye saram neŝasteh va ber o ber negāham mikonad.(p. 72) |

|

Word for word translation |

Rasool sits over my head like a cat and stares at me. (p. 72) |

|

Target Segment |

– |

|

Unit of Analysis |

Clause/sentence level: Finite clauses and sentences |

Table 7. Instance of Contraction-Replacement Shift

|

Source Segment in Persian |

|

|

Source Segment in Latin |

Ro kanal e Zowji do ta pol hasteŝ ke ehtemalan doŝman omdeh feŝareh xodeŝ ro mizareh ta az ro un begzareh. (pp. 96-97) |

|

Word for word translation |

There are two other bridges over the canal, and it is likely that the enemy will concentrate his forces there to pass over it- (p. 113) |

|

Target Segment |

There are two other bridges over the canal, and it is likely that the enemy will concentrate his forces there- (p. 113) |

|

Unit of Analysis |

Clause/sentence level: Finite clauses and sentences |

As the example in Table 6 reveals, a sentence in the source text, which carries information, is deleted in the target text, while in the example provided in Table 7, the long sentence in the source text is replaced with a short one in the target language and no information is missed.

• Order

Pekkanen (2010: 78) believes that “when discussing the order of expressions denoting time or place, both single adverbs and phrases with an adverbial function are included in the subcategories for time and place”. In line with the same discussion, she adds, “in many cases changes of order are obligatory, but when there are alternatives available, this offers a variety of shift options to the translator” (ibid. 78). She classifies order shift into order of time, “shift in the place of a time adverb or a phrase with an adverbial function expressing time,” order of place, “shift in the place of a place adverb or a phrase with an adverbial function expressing place”, and others (other cases which do not fall under the mentioned categories). Below, an example is provided to show the process of analysis for this type of shift.

Table 8. Instance of Order Shift

|

Source Segment in Persian |

|

|

Source Segment in Latin |

Bexon, bexon bābā tā qabul ŝi. Aqalakam az bacehaie mardom aqab naiofti va va nagan raft jebhe dars naxond. (p. 14) |

|

Word for word translation |

“study, study hard son, so you’ll be accepted to college. At least don’t fall behind other people’s kids, so they won’t say you went to the front and did not study. (p. 14) |

|

Target Segment |

“study, study hard son, so you’ll be accepted to college. At least don’t fall behind other people’s kids, so they won’t say you failed and had to go to the front”. (p. 28) |

|

Unit of Analysis |

Clause/sentence level: Finite clauses and sentences |

The statement ‘you failed and had to go to the front’, is a shift of order of time at the sentence level in which the order of some linguistic elements of the source text is changed in the target text.

• Miscellaneous Shifts

According to Pekkanen (2010: 131) “the category of miscellaneous shifts was created for shifts that could not be placed in any of the three main categories, expansion, contraction and order”. She adds, “Miscellaneous shifts comprise all optional formal shifts that did not fall into the categories of expansion shifts, contraction shifts and shifts of order” (2010: 78). Miscellaneous Shifts consist of tense (shift of tense), mood (shift of mood) which refers to the shift of modalities, deletion of repetition, agency (shift of agency in the sense that the acting agent in the narrative changes), (shift from active to passive-passive to active), referential relations (shift of referential relations), (singular to plural -plural to singular shift), and other cases (Pekkanen 2010).

• Referential Relations

Pekkanen (2010: 143) defines referential relations as “the choice of a certain noun or the choice of a noun instead of a pronoun or vice versa”. In the present study, referential relations and deixis are used interchangeably, since according to Yule (2010) referential relations, or ‘deixis’, are used when we want to point to other things. He classifies three types of deixis and introduces some deictic expressions for each one. His classification of deixis is as follows:

■ Person deixis: This type of deixis is used when we point to objects and individuals, like “(it, this, these boxes) and people (him, them, those idiots)” (Yule 2010: 130).

■ Spatial deixis: It includes “words and phrases used to point to a location (there, here, near that)” (Yule 2010: 130).

■ Temporal deixis: It relates to those deixis that are “used to point to a time (now, the, last week)” (Yule 2010: 130).

The present study adopts Yule’s (2010) definition of referential relations. In the example showed in Table 9, although the translator had the option to use the names Mehdi and Rasool, he contracted the phrase into a single word of ‘they’. Therefore, shift of referential relations or deixis has taken place at the phrase level and it falls under the category of person deixis.

Table 9. Instance of Miscellaneous shifts (Referential Relations)

|

Source Segment in Persian |

|

|

Source Segment in Latin |

Mehdi va Rassol qadamzanān dar ān soye xākrizi ke hael e bein e mā va rod e Karun ast, gom miŝavand. (p. 101) |

|

Word for word translation |

Mehdi and Rasool walking together toward the Karun River and disappear behind the pile of earth separating us from it- (p. 117) |

|

Target Segment |

They return walking together toward the Karun River and disappear behind the pile of earth separating us from it- (p. 117) |

|

Unit of Analysis |

Phrase level: All word combinations that are not finite clauses |

• Deletion of Repetition

Deletion of repetition happens when the repetitive element (word, phrase, clause or sentence) is deleted or replaced with “a different semantic equivalent” (Pekkanen 2010: 131). An example is provided in Table 10.

Table 10. Instance of Miscellaneous shifts (Deletion of Repetition)

|

Source Segment in Persian |

40 |

|

Source Segment in Latin |

Ezat ziād javon! Ezat ziād. (p. 40) |

|

Word for word translation |

Take care, young prince! Take care - (p. 58) |

|

Target Segment |

Take care, young prince! - (p. 58) |

|

Unit of Analysis |

Clause/sentence level: Finite clauses and sentences |

• Other Miscellaneous Shifts

It is necessary to mention that there were instances of the other miscellaneous shifts including shifts of agency, shifts of tense, shifts of singular to plural or vice versa, shifts of passive to active or vice versa found in the translation, which affected the source text not only formally but also semantically.

3. Research Findings and Discussion

Having compared carefully the source and translated texts, the following data was obtained. It should be noted that doubtful optional shift cases were excluded from the present research analysis. The total instances of expansion-additions including all levels of analysis were 203 (21.92%). Expansion-replacement was repeated 109 times (11.77%) throughout the respective novel, 24 times (10.9%) at the word level, 56 times (34.78%) at the phrase level, and 29 times (5.32%) at the clause/sentence level. This implies that in contrast to shifts of expansion-addition, most shifts of expansion-replacement were at the phrase level. Through the data analysis, it was revealed that the category of expansion shifts including expansion-addition and expansion-replacement was the most frequent shift type among other optional shifts with the frequency of 312 and 33.69 percent against the total 926 instances of optional shifts found in this study.

Contraction-deletion was repeated 112 times (12.09%) and most of the optional shifts of this type were at the clause/sentence level with the frequency of 102 (18.71%) according to which 5 instances of optional shifts (2.27%) happened at the word level and 5 instances of optional shifts (3.1%) happened at the phrase level. There were 123 instances of contraction-replacement shifts (13.28%) out of which 23 instances (10.45%) were at the word level, 32 instances (19.87%) at the phrase level, and 68 instances (12.47%) at the clause/sentence level. Optional shifts of this category were more frequent at the clause/sentence level. It should be noted that contraction-replacement was found to be the most frequent optional shift after expansion-addition.

Moreover, shifts of order, which were classified into three types of time, place and other shifts of order which did not fall under the time and place categories, all made 35 instances of optional shifts of order (3.77%). One instance (0.45%) was related to the word level, 4 instances (2.48%) to the phrase level and 30 instances (5.50%) to the clause/sentence level. Optional shifts of order were more frequent at the clause/sentence level. The other shift type was miscellaneous shift, which was broken down into various types. Miscellaneous shifts of passive to active and active to passive together made 22 instances (2.37%) out of which 2 instances (0.9%) were related to the word level and 20 instances (3.66%) to the clause/sentence level. However, no shift was found at the phrase level. In this shift type optional shifts were more recurrent at the clause/sentence level.

Miscellaneous shifts of singular to plural and plural to singular together made 22 instances equal to (2.37%) out of 926 optional shifts. 10 instances (4.54%) occurred at the word level, 7 instances (4.34%) at the phrase level, and 5 instances (0.91%) at the clause/sentence level. In this category, optional shifts occurred at the word level were more frequent than shifts happening at phrase level or clause/sentence level. Miscellaneous shifts of (deletion of repetition) were repeated 14 times (1.51%), 5 times (2.27%) at the word level, 5 times (3.10%) at the phrase level, and 4 times (0.73%) at the clause/sentence level. Miscellaneous (shift of tense) was repeated 15 times (1.61%) throughout the respective novel. It was repeated 7 times (3.18%) at the word level, 7 times (4.34%) at the phrase level, and one time (0.18%) at the clause/sentence level. In this category, optional shifts, which happened at the phrase and sentence level, had equal frequencies.

It should be mentioned that miscellaneous shift of modality was not found throughout the analysis. Miscellaneous (shift of referential relations) named as shift of deixis, made 100 (10.79%) optional shifts, 68 shifts were related to the word level, 20 (12.42%) shifts to the phrase level, and 12 (2.20%) shifts to the clause/sentence level. Statistics indicate that optional shifts of referential relations, which took place at the word level, were repeated more than other referential relation optional shifts, which happened at the other levels of analysis. Miscellaneous (shift of agency) was repeated 91 (9. 82%) times amongst which 57 (25.90%) shifts were related the word level, 11(6.83%) shifts to the phrase level, and 23 (4.22%) shifts to the clause/sentence level. According to the statistics, optional shifts of agency as well as optional shifts of deixis were more frequent at the word level.

Moreover, those miscellaneous cases that did not fall into the other categories of miscellaneous shift types, were classified into the category of miscellaneous shift cases, which made 36 (3.88%) optional shifts as a whole out of which 3 (1.36%) shifts were related to the word level, 3 (1.86%) shifts to the phrase level and 30 (5.50%) shifts to the clause/sentence level. In this category, the most repeated optional shifts fell under the category of clause/sentence level. Furthermore, in the miscellaneous category, deixis was the most frequent shift type with the total frequency of 100. Table 10 shows the frequency of the various categories of optional shifts at word, phrase and sentence levels.

Table 11. Frequencies of Various Categories of Optional Shifts

|

Frequency (%) of Optional Shifts |

||||

|

Types of Optional Shifts |

Word-level: |

Phrase level: |

Clause/sentence level: |

Total Optional Shifts at All Three Levels |

|

Expansion (addition) |

3 (3.1%) |

4 (2.48%) |

196 (35.96%) |

203 (21.92%) |

|

Expansion (replacement) |

24 (10.9%) |

56 (34.78%) |

29 (5.32%) |

109 (11.77%) |

|

Total expansion |

27 (12.27%) |

60 (37.26%) |

225 (41.28%) |

312 (33.69%) |

|

Contraction (deletion) |

5 (2.27%) |

5 (3.10%) |

102 (18.71%) |

112 (12.09%) |

|

Contraction (replacement) |

23 (10.45%) |

32 (19.87%) |

68 (12.47%) |

123 (13.28%) |

|

Total contraction |

28 (12.72%) |

37 (22.98%) |

170 (31.19%) |

235 (25.37%) |

|

Shift order of Time |

- |

1 (0.62%) |

- |

1 (0.10%) |

|

Shift order of place |

- |

2 (1.24%) |

- |

2 (0.21%) |

|

Shift order of other |

1 (0.45%) |

1 (0.62%) |

30 (5.50%) |

32 (3.45%) |

|

Total order shift |

1 (0.45%) |

4 (2.48%) |

30 (5.50%) |

35 (3.77%) |

|

Miscellaneous (deletion of repetition) |

5 (2.27%) |

5 (3.10%) |

4 (0.73%) |

14 (1.51%) |

|

Miscellaneous (active to passive) |

1 (0.45%) |

- |

5 (0.91%) |

6 (0.64%) |

|

Miscellaneous (passive to active) |

1 (0.45%) |

- |

15 (2.75%) |

16 (1.72%) |

|

Total shift of active-passive, passive- active |

2 (0. 90%) |

- |

20 (3.66%) |

22 (2.37%) |

|

Miscellaneous singular to plural |

5 (2.27%) |

6 (3.72%) |

3 (0.55%) |

14 (1.51%) |

|

Miscellaneous plural to singular |

5 (2.27%) |

1 (0.62%) |

2 (0.36%) |

8 (0.86%) |

|

Total Shift of singular – plural, plural to singular |

10 (4.54%) |

7 (4.34%) |

5 (0.91%) |

22 (2.37%) |

|

Miscellaneous (shift of tense) |

7 (3.18%) |

7 (4.34%) |

1 (0.18%) |

15 (1.61%) |

|

Miscellaneous (shift of modality) |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Miscellaneous (shift of referential relations) |

68 (30.90%) |

20 (12.42%) |

12 (2.2%) |

100 (10.79%) |

|

Miscellaneous (shift of agency) |

57 (25.90%) |

11 (6.83%) |

23 (4.22%) |

91 (9. 82%) |

|

Miscellaneous Cases (all other optional formal shifts that did not fall into the other categories) |

3 (1.36%) |

3 (1.86%) |

30 (5.5%) |

36 (3.88%) |

|

Total miscellaneous shift |

164 (74.54%) |

60 (37.26%) |

120 (21. %) |

344 (37.14%) |

|

Total shifts |

220 (100%) |

161 (100%) |

545 (100%) |

926 (100%) |

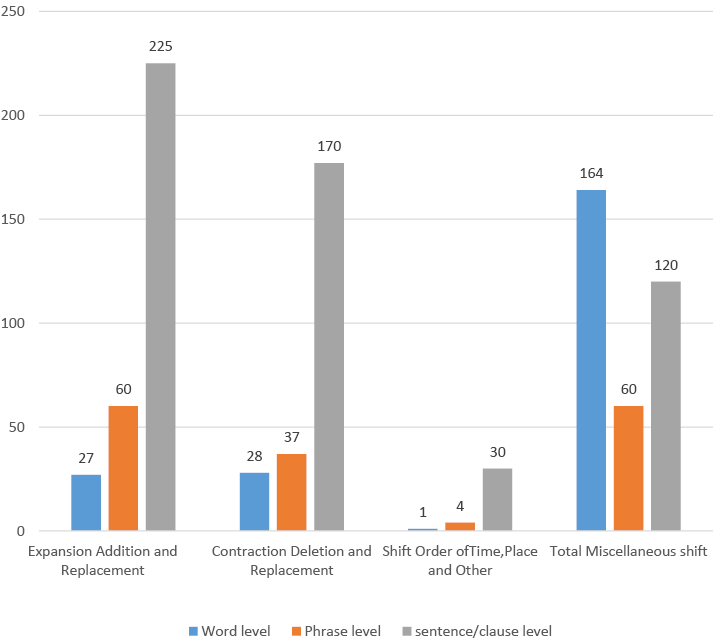

To have a better overview, the distribution of various types of optional shifts at each level of analysis is illustrated in the following figure.

Figure 1. Distribution of optional shifts through each level of analysis

As it can be seen, expansion-addition was the most frequent optional shift used by the translator. This result is in line with Pekkanen’s (2010: 80) statement who claims, “there is reason to assume that expansion is a fairly common translation shift”. Based on previous research done by Blum-Kulka (1986), Laviosa (2001), Olohan and Baker (2000), Pekkanen (2010: 80) concludes that “expansion is a universal feature in translation”.

4. Conclusions

The many instances of optional shifts of expansion including expansion-addition and expansion-replacement identified in this study imply that the translator of the Persian novel opted to either add information to the Persian source text or replace the information in the source text in some parts of his English translation. Furthermore, a rather high number of optional shifts of contraction including contraction-deletion and contraction-replacement identified imply that the translator in some parts of his translation chose not to transfer the exact information in the source text into the target text and he did it through either deleting or replacing the information in the source text. There were also many instances of miscellaneous shift cases identified, which affected the information transferred to the target readers.

Such optional shifts when happen at large can form a pattern, which can alter the narrative of the source text. According to Pekkanen (2010), the recurrent optional shifts can affect the degree of specification as a narrative element. Pekkanen (2010: 141) asserts that “the degree of specification may shift in translation if information is added, deleted or changed”. Moving from microanalysis to macro-textual level, our next step can be examining the effect of optional shifts on the source text’s narrative elaborating on if and how a translator can change the source text’s narrative.

References

Al-Qinai, Jamal. 2009. Style shift in translation. Journal of Pan-Pacific Association of Applied Linguistics, 13(2). 23–41.

Blum-Kulka, Shoshana. 1986. Shifts of cohesion and coherence in translation. Interlingual and Intercultural Communication, edited by Juliane House and Shoshana Blum-Kulka. Tubingen: Narr. 17–35.

Catford, John Cunnison. 1965. A Linguistic Theory of Translation: An Essay in Applied Linguistics. London: Oxford University Press.

Chesterman, Andrew. 2004. Beyond the particular. Translation Universals. Do they Exist?, edited by Anna Mauranen and Pekka Kujamaki. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. 33–49. https://doi.org/10.1075/btl.48.

Farahzad, Farzaneh. 2012. Translation criticism: A three dimensional model based on CDA. Journal of Translation Studies, 9(36). 27–44.

Glaser, Barney Galland and Anselm Leonard Strauss. 1967. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Chicago: Aldine.

Habibi, Tayebeh. 2016, July 27. Re: Journey to Heading 270 Degrees [Online forum comment]. Retrieved from: http://ido.ir/en/pages/?id=353.

Haiman, John and Sandra Annear Thompson (eds). 1988. Clause Combining in Grammar and Discourse. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Klaudy, Kinga. 2003. Languages in Translation. Budapest: Scholastica.

Larson, Mildred Lucille. 1984. Meaning-based Translation: A Guide to Cross-language Equivalence. The United States: University Press of America.

Laviosa, Sara. 2001. Corpus-based Translation Studies: Theory, Findings, Applications. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

Leech, Geoffrey Neil and Mick Henry Short. 1981. Style in Fiction. London: Longman.

Leuven-Zwart, Kitty Marguerite. 1989. Translation and original: similarities and dissimilarities I, Target 1(2). 151–181. https://doi.org/10.1075/target.1.2.03leu.

Olohan, Maeve and Mona Baker. 2000. Reporting that in translated English: Evidence for subconscious processes of explicitation, Across Languages and Cultures 1(2). 141–158. https://doi.org/10.1556/acr.1.2000.2.1.

Pekkanen, Hilkka. 2010. The duet of the author and the translator: Looking at style through shifts in literary translation. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, University of Helsinki.

Popoviĉ, Anton. 1970. The concept ‘Shift of Expression’ in translation analysis. The Nature of Translation: Essays on the Theory and Practice of Literary Translation, edited by James S. Holmes. The Hague & Paris, Bratislava: Mouton, Slovak Academy of Sciences. 78–90. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110871098.78.

Toury, Gideon. 1995. Descriptive Translation Studies and Beyond. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Vinay, Jean-Paul and Jean Darbelnet. 1991. Stylistique comparée de français et de l’anglais:ā Méthode du traduction. Comparative Stylistics of French and English, translated and edited by Juan C. Sager and Marie Josée Hamel. Amsterdam, Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Yule, George. 2010. The Study of Language (4th ed.). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Sources

Dehghan, Ahmad. 2014. Safar be garāye 270 darajeh (20th ed.). Tehran: Soreie Mehr Publication Company.

Dehghan, Ahmad. 2006. Journey to Heading 270 Degrees, translated by Paul Sprachman. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publication House.

1 Ahmad Dehghan, the author of the novel, became famous for his first novel ‘Journey to Heading 270 Degrees’. “The first edition was published by Sarir Publishing Company in 1996. It was reprinted thereafter. In 2005, Soreie Mehr Publishing Company published its second edition” (Habibi 2016, para. 4). The novel has been reprinted twenty-seven times by the same publishing house.