Vertimo studijos eISSN 2029-7033

2022, vol. 15, pp. 30–46 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/VertStud.2022.2

Latvian Original Adverts and Translations in the 1920s and 1930s

Gunta Ločmele

Department of Contrastive Linguistics,

Translation and Interpreting

Faculty of Humanities

University of Latvia

gunta.locmele@lu.lv

ORCID 0000-0002-6094-2791

Abstract. Advertisements in the 1920s and 1930s Latvia were published mainly in Latvian, German and Russian. Besides original adverts for local products, there were numerous translations of advertisements, mainly from German. Translations of translations also circulated in the press, blurring the concept of a source text. Advertising, including translated adverts, made an impact on culture, glorifying feminine beauty in many cases but trivialising women by a specific use of language in others. Advertising also influenced the Latvian language itself. Translators added a second layer of German calques to the ones that already existed. However, new terms coming from adverts also enriched the language. Translations helped create the language of advertising as such, by developing its constituent parts: brands and slogans.

Keywords: translated adverts, adverts of the 1920s and 1930s, language of advertising, brand

______

Copyright © 2022 Gunta Ločmele. Published by Vilnius University Press

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

At the beginning of the 20th century, with the growth of production and competition in Latvia, the importance of advertising increased. Articles on the significance of advertising appeared in the Latvian press. For instance, the author of the article “80,000 lats for button advertising” stated: “the age has begun in which the one who knows how to publicise his stuff in the most beautiful, special and sometimes even loudest way wins.” (80,000 latu par pogu reklāmu 1936: 2). Advertising reached out to quite a varied audience. In 1935, Latvia’s total population was almost 2 million. Of them close to 1.5 million (75.5 per cent) were Latvians, 206,000 (10.6 per cent) were Russians, 93,000 (4.8%) were Jews, 62,000 (3.2%) were Germans. There resided Poles, Belorussians, Lithuanians, Estonians and people of other nationalities (Latvijas statistikas gada grāmata 1936: 8). For these target audiences, 22 newspapers were published in 1920, and as many as 168 in 1931. After the coup d’état of 1934, which brought the closure of many newspapers, their number fell to 47 in 1936. Of them 33 (70.2 per cent) were in Latvian, 7 in German, 4 in Russian, 2 in Yiddish, and 1 in Lithuanian (Salnītis 1938: 138). Newspapers and magazines were the main media for adverts. The material for the present study is taken from the daily newspaper Jaunākās Ziņas with a circulation of 200,000 copies (Brempele et al. 1988: 215 – 217); Brīvā Zeme (a daily newspaper of the Latvian Farmers’ Union), circulation 18,000 (ibid. 76 – 78); the daily newspaper Rīts, circulation 18,850 (ibid. 530 – 531); the German-language weekly Rigasche Post, circulation 8000 (Treijs 1996: 434) and magazines: the Russian-language Dlya Vas (referred to as the best Russian magazine published in Latvia at that time (20. gadsimta Latvijas vēsture 2. sēj. Neatkarīgā valsts 1918 – 1940, 2003: 776)); the Latvian Atpūta, circulation 70,600 (Brempele et al. 1988: 44 – 45) and Sievietes Pasaule. The object of this study is the translation of adverts, the cultural impacts of advertising and the impact of advertising on the Latvian language.

1. Translations

Adverts for imported products were translated, mostly from German. The advert for the Original-Hanau tanning lamp, one of the most modern devices of the time (Bormane 2017: 115), can serve as an example of a rather free translation from German. The headline was changed from “Rüstzeug fürs Leben!”1 [A tool for life!] to “Ko dod mākslīgā kalnu saule?”2 [What does the artificial mountain sun give?]. The beginning of the first sentence of the German text, “Immer wieder bestätigt sich’s:” [It is confirmed again and again:] is omitted in Latvian. The meaning of the sentence “Der Mensch fühlt sich wieder frei” [You feel free again] is slightly changed. It is translated with a set expression sveiks un vesels [literally, safe and sound, meaning healthy]. Although the translation is free, there are features of translationese such as the calque mākslīgā kalnu saule [artificial mountain sun] from the German künstliche Höhensonne and of almost word-for-word translation of an sein Tagewerk [to his daily work], savā darbā.

Translations were sometimes even made from Latvian into German. One example is a product from the German chemical company Hans Schwarzkopf in Berlin Tempelhof, that registered the Latvian transcription Švarckopf with the Patent Board of Latvia (Patentu ziņas 1936). An advert for Schwarzkopf shampoo in German used a Latvianised product name: “Vēl skaistāki kļūs Jūsu mati caur ŠVARCKOPF ŠAMPUNU ar “Matu spīdumu”. “Matu spīdums” sniedz dabīgu mirdzumu”3 [Your hair will become even more beautiful through Schwarzkopf shampoo with Hair Shine. Hair Shine gives a natural gloss]. “Matu spīdums” [hair shine] is a calque from German Haarglanz and the Latvian construction with the preposition caur [through] is a syntactic calque from German. The same text was available in German: “Noch schöner wird Ihr Haar durch ŠVARCKOPF-ŠAMPUNU mit Haarglanz. Haarglanz gibt natürlichen Glanz”4. The accusative noun šampunu, a Latvian word in a German text, reveals that it is a translation from Latvian. There is some eclecticism and cross-interference in this: the Latvian text has German traits, and the German text has Latvian features (e.g. a Latvian case ending). The Rigasche Post published Švarckopf ads with even stronger Latvian interference: “Wundervoll glänzendes Haar. ŠVARCKOPF-ŠAMPUNU mit “Haarglanz”5 where the Latvian accusative ending made the German text illogical as it requires the nominative. Later, a calque of the brand name Schwarzkopf [black head] was used: the shampoo for greasy hair was called Melnā galva [the black head] and was produced according to the original Schwarzkopf recipes, as claimed in the advert: “Pret taukainiem matiem ŠAMPUNS MELNĀ GALVA ar “Matu spīdumu” pagatavots pēc “Švarckopfa” origināl-receptēm.”6 [For oily hair BLACK HEAD SHAMPOO with Hair Shine, made according to the original Švarckopf recipes].

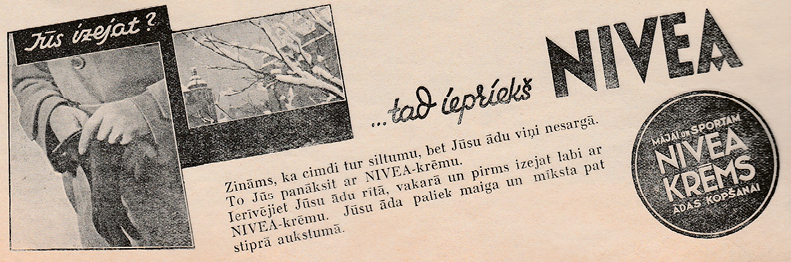

There were Latvian and German versions of the same adverts in the local press (Figure 1, Figure 2). For example, the adverts for Nivea in both languages warn that gloves did not always protect your skin and you needed Nivea cream to keep your skin soft. There is a unit shift between the versions at the beginning of the body copy: there are two sentences in the German version, “Sicher, Handschuhe halten manchmal warm” [Sure, gloves sometimes keep you warm] and “Ihre Haut beschützen sie nicht” [They do not protect your skin], but only one compound sentence in Latvian. The cohesion in the German and Latvian sentences is different, as the second Latvian clause is introduced by the conjunction ”but”. The first part of the introductory Latvian sentence is more affirmative about the ability of gloves to keep you warm than in the German advert.

Figure 1. Atpūta. 1936. No. 631, 04.12.: 23

Figure 2. Rigasche Post. 1936. Nr. 58, 13.12

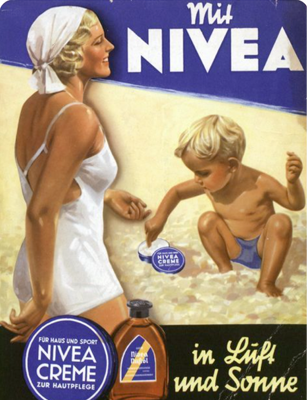

According to Bormane (2017: 109), Nivea cream was produced at A. Rimeiks’s chemical factory in Riga. Although Nivea was produced in Latvia, its adverts were in many cases translated from German. For instance, the poster with the German slogan “Mit NIVEA in Luft un Sonne” (Figure 3) is from 1930s Germany, and the same picture was used in the Latvian magazine Atpūta in 1936 (Figure 4) and a very similar one in the Russian magazine Dlya Vas in 1935. The headline, which is also a slogan, is a word-for-word translation from German into Latvian: “Ar NIVEA gaisā un saulē!”7 [With Nivea in the air and in the sun], but the Russian translator has used expansion: the headline contains a translator’s gloss “Съ кремомъ NIVEA на воздухѣ и солнцѣ!”8 [With Nivea cream in the air and in the sun!]. The Russian text is more expressive, it reads: “Чудесно… это ничегонедѣланіе” [Wonderful…doing nothing] where the Latvian copy has just “Tas ir patīkami… Jauki tā slinkot” [It is pleasant… It is nice to laze] with a semantic repetition (the synonyms patīkami and jauki repeat the same meaning: nice). Another instance where the Russian text is more expressive is the sentence “Tā Jūs sekmīgi novērsīsit saules deguma briesmas” [In this way you will successfully avert the danger of sunburn] in Latvian where the Russian copy has “Такъ Вы умаляете опасность болѣзненнаго солнечнаго ожога” [In this way you decrease the danger of a painful sunburn] with an attribute болѣзненнаго [painful] added. There is an awkward sentence in the Russian text with two members of the sentence illogically connected (a noun and an infinitive are connected as equal sentence members, making the same word чудесно they are related to into an adjective and an adverb): “Чудесно… это ничегонедѣланіе и загорать на солнцѣ” [literally, Wonderful…doing nothing and to bathe in the sun]. The Russian text is thus more explicit and expressive. The Latvian text is longer. It has two additional sentences, one in the middle and another at the end of the text. We should take into account, however, that there is a timelag between the two texts’ publication dates (Latvian in 1936 but Russian in 1935), and there might have been different versions of the source text.

Figure 3. https://www.pinterest.co.kr/pin/831477149937123030/ (accessed 18.06.2022)

Figure 4. Atpūta. 1936. No. 608, 26.06.: 21

There were Latvian, German and Russian versions of the same adverts in the Latvian press, for example the advert for Nivea toothpaste (Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7) (Nivea toothpaste was produced in Latvia by the company Pilot). The text of the advert consists of three sentences in all three languages (Table 1).

Figure 5. Atpūta. 1936. No. 625: 15

Figure 6. Для Вас: Еженед. ил. Журн. 1936. No. 27

Figure 7. Rigasche Post 1936. No. 53

Table 1. Nivea toothpaste adverts 1936

|

Latvian (Atpūta. 1936. No. 625: 15) |

Russian (Для Вас: Еженед. ил. Журн. 1936. No. 27) |

German (Rigasche Post 1936. No. 53) |

|

Latvian (Atpūta. 1936. No. 625: 15) |

Russian (Для Вас: Еженед. ил. Журн. 1936. No. 27) |

German (Rigasche Post 1936. No. 53) |

|

“NIVEA zobu pastu visi lietā viņas labās iedarbības dēļ un arī labās garšas dēļ.” [NIVEA toothpaste is used by everyone for its good effects and also for its good taste] |

“Зубную пасту НИВЕА всѣ употребляютъ изъза хорошаго дѣйствiя и прiятнаго вкуса.” [NIVEA toothpaste is used by everyone for its good effects and also for its good taste] |

“Die Wirksamkeit der NIVEA - Zahnpasta, ihr angenehmer Geschmack sind entscheidend für die Wahl dieser Zahnpasta.” [The effectiveness of NIVEA toothpaste and its pleasant taste are decisive for the choice of this toothpaste] |

|

“Pateicoties vislabākām jēlvielām NIVEA zobu pasta garantē pilnīgu zobu kopšanu.” [Thanks to the best raw materials, NIVEA toothpaste guarantees complete dental care] |

“Отборное сырье при изготовленіе зубной пасты является лучшей гарантіей для совершеннаго ухода за зубами.” [Selected raw materials in the manufacture of toothpaste are the best guarantee of complete dental care] |

“Mit ihren erlesenen Rohstoffen bietet NIVEA – Zahnpasta die Gewähr einer vollkommenen Zahnpflege.” [With its select raw materials, NIVEA toothpaste offers the guarantee of perfect dental care] |

|

“Veselīgi, stipri un spīdoši balti zobi norāda uz NIVEA zobu pastas lietāšanu.” [Healthy, strong and shiny white teeth indicate the use of NIVEA toothpaste] |

“Oсобыя преимщества: легкая, нѣжная пѣна, способность основательного очищенія зубовъ и пріятный вкусъ.” [Special advantages: light, gentle foam, the ability to thoroughly clean the teeth and a pleasant taste] |

“Die besonderen Vorzüge: leichter, feiner Schaum, gründliche Reinigungskraft un angenehmer Geschmack.” [The special advantages: light, fine foam, thorough cleaning power and pleasant taste] |

The first sentence is similar in Latvian and in Russian albeit with a slight cohesion difference, while its structure differs in German due to the peculiarities of the German language. The Latvian text has a calque normal in the Latvian of the time: jēlvielas from German Rohstoff [raw materials]. The Russian text has more additions that explicitate and intensify the meaning and make the text more expressive. The last sentences in German and Russian are similar with an explicitation in Russian, however the last sentence in Latvian is different: it is a repetition of the headline, “Veselīgi, stipri un spīdoši balti zobi norāda uz NIVEA zobu pastas lietāšanu.” [Healthy, strong and shiny white teeth indicate the use of NIVEA toothpaste]. The brand name, Nivea, is repeated three times in the Latvian text and twice in the German text, while it is mentioned only once in the Russian text, which is compensated by the addition of the brand name Nivea in red as a caption to the picture.

In general, the Russian versions are more expressive and more explicitation is used.

The German influence is observed in the advert for Orient Henna Shampoo, produced by the Alberto Gothemere chemical company in Germany (Interesanta chronika 1931). The Latvian version contains an antonymic pair sirmi – nesirmi mati [grey – non-grey hair]9. Judging by the same antonymic pair ergrautes – nichtergrautes Haar10 used in the German version, Latvian nesirmi [non-grey] is a calque from German. It is not used in modern Latvian. The Russian advert also contains the same pair седые – не седые волосы11. The German text probably served as a source text for the Latvian version although there are additions in Latvian “vienkārši mazgājot” [simply by washing] and “līdz vistumšāki melnai”[to darkest black] but the Russian translation was probably made from Latvian, as it has exactly the same addition, “обыкновенным мытьем” [by simple washing]. Also, the Latvian advert does not contain the German syntactic calque with caur, German durch, as was the case in Swarzkopf ads, but the construction “ar “Orient Henna Shampoo” palīdzību” [with the help of “Orient Henna Shampoo”] as used in modern Latvian. The Russian version has the same construction as Latvian with an addition: “возможно с помощью “Orient Henna Shampoo” [is possible with the help of “Orient Henna Shampoo”]. The end of the final sentence has been cut off in the Russian translation and the sentence “Продается везде” [Sold everywhere] added.

Thus translations of translations circulated in the press, blurring the concept of the source text. The same versions of adverts were used for several years. Speaking about literary translations of the time, Andrejs Veisbergs writes about the lack of clearly defined borders and merging of translation and original (Veisbergs 2022: 19; see also Hermans 1996: 43). The language of advertisements demonstrates the same thing. There is also merging of translationese and normal language (Veisbergs 2022: 19; 2009) in a translated text: a second layer of German calques was produced in advertisements, adding to the one already existing in the language.

2. Formation of brands

Brands were transcribed and registered with the Patent Office, identifying the owner of the brand in a foreign country as in the case of the German brand Švarckopf šampuns, or simply transcribed, for instance the cosmetic brand Dortis, transcribed from the French D’Hortys. The French perfume and cosmetics brand D’Hortys was created by Max Heidelberg in Neuilly-sur-Seine (Perfume Intelligence 2022) in 1917. In Latvia, imported D’Hortys products were sold along with others produced locally in the Ambroko laboratory according to the recipe of the Parisian perfumer Maurice Blanchet (1890-1953) (Memoriālo muzeju apvienība 2022). The brand was used both with the French spelling and in the transcribed form.

A brand name might also be borrowed for a different product, for example German Nirosta, the trade name of the stainless steel alloy obtained at the Krupp steelworks in 1912, an acronym of nichtrostende Stähle [non-rusting steel] (Cobb 2007: 39). In 1935, the Patent Board of Latvia registered the logo Nirosta for the steel products, especially razor blades, produced by the company Saturn, S. Genins in Riga (Valdības Vēstnesis 1935). The form of the borrowed word was not changed.

Brand names were also borrowed for the same product, for example Extase powder by D’Hortys, transcribed into Latvian as Ekstaze. The brand name was Latvianised and was used both with the French spelling and in the Latvianised form.

There were hybrid forms as well, for example, Gütermaņa šujamais zīds [Gütermann’s sewing silk] with half-German, half-Latvian spelling.

A gradual adaptation of brand names was taking place. The brand name of Nivea cream was first introduced in its German form, Nivea-Creme. It was a feminine noun and declined using an apostrophe: Nivea-Creme’s,12 which is foreign to Latvian. Later, a hybrid spelling appeared with a Latvian macron over the German name, Nivea-Crēme,13 and, from February 1936, a Latvian name of masculine gender was used: Nivea-krēms14.

Under the influence of foreign cultures local brands sometimes acquired a foreign flavour. A French acute accent to indicate French pronunciation was added to the brand names ELPÉ pūderi [ELPÉ powders], ELPÉ sejas piens [ELPÉ facial milk], ELPÉ preparāti [ELPÉ preparations]15 produced by beautician Elza Pērkone, who had acquired her professional skills in Paris, Vienna and Berlin. The brand name was made from the first syllables of her name. The acute accent added a special Frenchness to her cosmetics. However, there were advertisements in which the brand had Latvian spelling: “Skropstu un uzacu kopšanas krēms “Elpē”” [Elpē eyelash and eyebrow-care cream]16.

Some local brand names were concocted from foreign words, for example in cosmetics, Bosex, probably from French Beau Sexe, as the Patent Board announced registration of the full French name, Beau Sex, which had the English spelling, for the same company’s products (Latvijas Farmaceitu Žurnāls 1935). French names were popular in cosmetic products, but also in the manufacture of fabrics, for example Kloké, a firm, thin woollen georgette17. Some other Latvian brands acquired German names. All in all, the picture was very mixed as Latvians advertised French brands, but also produced cosmetic products according to French recipes and under the influence of other cultures gave local cosmetic products French, German and other foreign names (among them, Frankolin roku ziepes [Frankolin hand soap] produced in P. Putniņš’s chemical laboratory18).

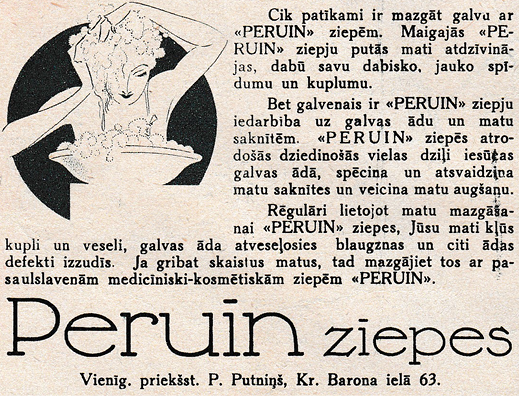

3. The impact of translations on slogans and content

Translated adverts made an impact on the development of constituent parts of Latvian adverts. There were translated slogans, such as one literally translated from German “Gut rasiert – gut gelaunt!”19: “Labi skuvies, labi jūties!”20 [well shaved, feel good] for Rotbart razor blades. In the local adverts, slogans were included at the end of the text, as “Tikai reiz Švarckopfa-Šamponu, vienmēr Švarckopfa-Šamponu”21 [Once Schwarzkopf-Shampoo, always Schwarzkopf-Shampoo]. Some of them contained words of the same root: “Samta pūderis samtainai ādai!”22 [Velvet powder for velvety skin]. Sometimes the slogans, also called mottos in advertisements, were quite long, such as the one for Peruin toothpaste: ““Peruin” devīze: - veselīgi, skaisti, balti zobi, patīkams aromats mutē, tīra, svaiga elpa un oikonomija, jo lielā tūba maksā tikai 75 sant., tā pietiek ilgam laikam.”23 [The motto of Peruin: healthy, beautiful, white teeth, a pleasant taste in the mouth, clean, fresh breath and value for money, because a big tube costs only 75 santīmses and lasts a long time].

The same brand Peruin, but spelt Peruīn, with a Latvian macron, offered the same content to women and men in adverts where nothing except the picture of an addressee was changed (Figure 8 and Figure 9). Different content when advertising the same product to women and men came into advertising from translated adverts. For women, the benefits of the artificial sun lamp were offered at different stages of a woman’s life: from pregnancy, then breast-feeding to menopause24. In another advert, a sun lamp was advertised to parents as providing protection against various childhood diseases such as rickets, scrofula and whooping cough25. The same product was advertised to men as effective against nervous disorders26.

Figure 8. Atpūta. 1936 No. 594, 20.03.: 15

Figure 9. Atpūta. 1936. No. 592, 06.03.: 2

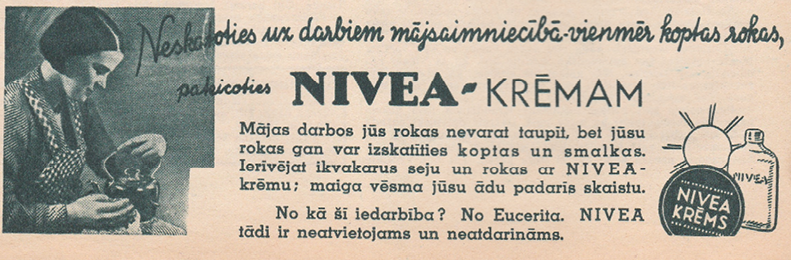

4. Cultural influences of advertising

Although some traits of feminisation are observed in the translated language (the neutral German “Jung und schön sein”27 [to be young and beautiful] was translated into Latvian as feminine, “Jaunai un skaistai izskatīties”28). Gender roles were depicted traditionally. As the headline runs in the advert for Nivea cream (Figure 10): “Neskatoties uz darbiem mājsaimniecībā – vienmēr koptas rokas, pateicoties NIVEA-KRĒMAM” [Despite your housework, your hands stay nice thanks to NIVEA-cream]. Another Nivea cream advert contained the same message: “Nedz nejauks laiks, nedz mājas darbi nevar kaitēt ādai, kuru kopj ar NIVEA. - … NIVEA nepieciešams, lai paliktu jauna un skaista”29 [Neither bad weather nor household work can harm the skin you care for with NIVEA. - …NIVEA is needed to stay young and beautiful]. Advertising helped to perpetuate such conceptions.

Figure 10. Atpūta. 1936. No. 621, 25.09.: 20

Advertising also trivialised women. The patronising diminutive mutīte, a little mouth, trivialised woman in the advertisement for Peruin toothpaste: “Skaista sievietes mutīte nav domājama bez sniegbaltiem, veselīgiem zobiem un patīkama mutes aromata…. Zobi kļūst tik veselīgi, pērļu balti, ka izsauc klātesošo sajūsmu.”30 [A woman’s pretty little mouth is unthinkable without snow-white, healthy teeth and a pleasant mouth odour…. Teeth become so healthy and pearl white, delighting everyone around.].

The obsession with beauty and the many beauty-product advertisements were a feature of the epoch: Riga was one of the oldest metropolises of the Old Continent where all the latest trends of modern beauty were echoed immediately or at least swiftly (Bormane 2017: 107). Midziņš-Vestena, a well-known beautician who graduated with honours from the Paris Beauty Academy and had a beauty parlour for women and men in Riga, wrote: “Life shows that beautiful, fresh, healthy young women win everywhere, at work, in everyday life, in love, in their careers… Beautiful women walk down the middle of the road and do not give way to anyone. Beauty today is a symbol of success and victory.” (Midziņš-Vestena 1934: 4).

There were dissenting opinions as well, such as this one in the press:

The cult of the body has promoted the cult of beauty care… The women who leave these beauty institutes all look almost the same. The same heart-shaped doll’s mouth, porcelain cheeks, eyebrows painted with mascara. There is sometimes little difference in appearance between daughters, mothers and grandmothers. (Technika un ķimija daiļuma kalpībā 1930: 2).

Cosmetic surgery was popular in Riga among women who were not satisfied with their faces, noses or breasts. Adverts helped to sustain beauty fashion trends, for example a Nivea cream ad promising a stylish brown sporty look for the skin.31

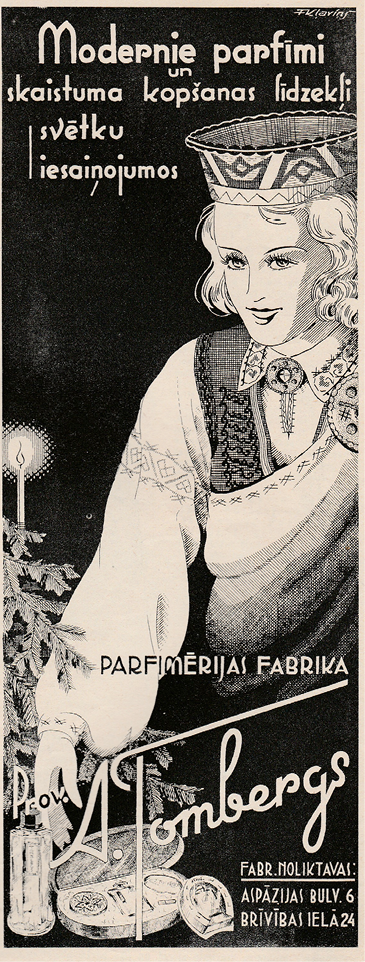

The glorification of beauty was found in advertising, and a modern woman in folk dress was used by Latvian cosmetics producer Tombergs as a symbol of Latvian beauty (Figure 11). Before the First World War he had cosmetics companies in Moscow and Odessa, but he lost everything in the Soviet revolution, returned penniless to Latvia but managed to establish a cosmetics factory that successfully competed with German and French producers (Bormane 2017: 109).

Figure 11. Atpūta. 1935. No. 581, 20.12.: 23

5. The impact of advertising on the Latvian language

Besides its cultural impact, advertising influenced the development of the Latvian language itself. Lexis was borrowed from German and French. From German came the semantic borrowing brūnināt in the meaning ‘to get a tan’, from bräunen (using the normal Latvian word brūns [brown]), saules degums [sunburn], a translation loan from Sonnenbrand, a product Matu spīdums from Haarglanz, normaltūbiņa [normal-size tube] from die normale Tube, šampons [shampoo] from Shampoon. From French came lotions (from lotion), mats (from mat)[matt skin] bouclé, a fabric made of looped yarn, spelled in French in advertising), demi-saison, used in the quotation marks to show its foreignness and used together with more assimilated French borrowing galošas (from galoches) [galoshes], rouge and others.

There were syntactic influences mainly from German, from where syntactic borrowing took place, for example, zem saules un vēja iespaida [under the influence of the sun and the wind] from German unter dem Einfluss von Sonne und Wind. An attributive modifier after the noun it modifies was rare in Latvian at the time (Veisbergs 2022) but is still observed in some adverts: pēdējā mode pirmā labuma [the latest fashion of the first quality]. And constructions with caur (the benefit is obtained through the product) from German durch were used.

Some influences were negative, such as syntactic ones that perpetuated the German constructions that already were used or, in some instances, even revived those German constructions that had been ousted, some influences were transient, some borrowings such as matu spīdums for hair shine, have survived to this day.

Several terms passed through advertising into everyday language. For example, the term eucerīts32 was used in Nivea adverts. The discovery of eucerit, an emulsifier obtained from sheep’s wool fat, was the basis for Nivea cream. It was the first water-in-oil emulsifier. Another term, cholerins33, denoted a substance similar to skin fats reportedly discovered in a well-known cosmetics laboratory (Jaunakais ahdas resp. skaistuma higienā 1934). It was produced in P. Putniņš’s cosmetics laboratory and was added to their product Panacea cream. The term was used in the advertisement for the cream. The term cholerins, however, has not stood the test of time.

The spelling of the borrowed words was unstable, as in the case of the noun shampoo that was spelt as šampons, šampuns, sampūns and showed a gradual phonetic assimilation. The borrowing lotion was assimilation from transliteration, lotions, to transcription, losions.

Grammatical assimilation was also taking place, for example in the case of the term eucerits. It was declined by adding an apostrophe, eucerit’u, thus underscoring its German origin, but also sometimes without the apostrophe in accordance with the Latvian grammar: euceritu.

Conclusions

A cult of the body fostered the cult of beauty care, with advertising making an impact on how people, especially women, perceived their bodies. Advertisements helped to sustain beauty fashion trends. Advertising, including translated adverts, made an impact on culture, glorifying feminine beauty in many cases but also trivialising women by a specific use of language in others.

Advertisements in the 1920s and 1930s Latvia were published mainly in Latvian, German and Russian. Although many products of foreign brands were produced in Riga, adverts for them were translations of foreign originals. Although there are a few cases of translation from Latvian into German.

Translations were free adaptations with some features of translation language. The boundaries between source texts and target texts were blurred, and translations of translations showed eclecticism and linguistic cross-interference.

In translations, a second layer of calques was added to ones already existing in the language. However, advertising translators-copywriters also enriched the language by providing it with new terms and features that have stood the test of time. Translations made an impact on the formation of the language of advertising itself by developing its constituent parts, brands and slogans.

References

Bormane, Anita. 2017. Skaists bij’ tas laiks… Latvijas dzīves ainas 20. gs. 20.–30. gados.[It was a Beautiful Time… Scenes from Life in Latvia in the 20th–30th Years of the 20th Century]. Rīga: Latvijas Mediji.

Brempele, Ārija, Ērika Flīgere, D. Ivbule, L. Lāce, M. Lazdiņa. 1988. Latviešu periodika. [Latvian Periodicals] 3. sējums 1920-1940, 1. daļa. Rīga.

Cobb, Harold M. 2007. The naming and numbering of stainless Steels. Advanced Materials & Processes. September 2007, 39 – 44. Accessed June 22, 2022: https://www.asminternational.org/documents/10192/1897460/amp16509p039.pdf/2c98eb5e-746f-4e34-a6c3-161d600f801d.

Hermans, Theo. 1996. Norms and determination of translation: A Theoretical Framework. Translation, Power, Subversion. Edited by Roman Alvarez and M. Carmen-Africa Vidal. 24–51. Cleveland/Philadelphia/Adelaide: Multilingual Matters Ltd.

Interesanta chronika [An Interesting Chronicle]. 1931. Filma un skatuve. No. 60, 24.10.

Jaunakais ahdas resp. skaistuma higienā [The Latest in the Skin, i.e., Beauty Care]. 1934. Atpūta, No. 493, 13.04.,18.

Latvijas Farmaceitu Žurnāls [Magazine of Latvian Pharmacists]. 1935. No. 5, 01.05.

Latvijas statistikas gada grāmata 1936 [Latvia’s Yearly Book of Statistics 1936]. 1937. Rīga.

Memoriālo muzeju apvienība. 2022. Skapītī ar atvilktnīti [In a Cabinet with a Drawer]. Accessed June 22, 2022: https://memorialiemuzeji.lv/stories/skapiti-ar-atvilktniti/

Midziņš-Vestena, Lidija. 1934. Skaistuma nozīme sievietes dzīvē [The Role of Beauty in Woman’s Life]. Cēsu Vēstis. No. 55, 20.07., 4.

Patentu ziņas [Patent News]. 1936. Valdības Vēstnesis. No. 290, 21.12.

Perfume Intelligence. 2022. Perfume Intelligence: The Encyclopaedia of Perfume. Accessed June 22, 2022: https://www.perfumeintelligence.co.uk/library/perfume/d/d5/d5p1.htm

Salnītis, Vilmārs. 1938. Latvijas kultūras statistika 1918. – 1937. g. [Statistics of Latvia’s Culture 1918 –1937]. Edited by M. Skujenieks. Valsts Statistiskā pārvalde. Rīga: Valtera un Rapas akc. sab. grāmatspiestuve.

Technika un ķimija daiļuma kalpībā [Technology and Chemistry at the Service of Beauty]. 1930. Latvijas Kareivis. No. 211, 18.09., 2.

Treijs, Rihards (Ed.). 1996. Latvijas Republikas prese 1918 – 1940 [The Press of the Republic of Latvia 1918 – 1940]. Rīga: Zvaigzne ABC.

Valdības Vēstnesis [ Government Herald]. 1935. No.93, 25.04.

Veisbergs, Andrejs. 2009. Translation language: The major force in shaping Modern Latvian. Vertimo Studijos, 2. Vilnius: Vilniaus Universiteto Leidykla, 54–70. https://doi.org/10.15388/vertstud.2009.2.10603

Veisbergs, Andrejs. 2022. Tulkojumi latviešu valodā: 16. – 20. gs. ainava [Translations into Latvian: 16th – 20th Century Scene]. Rīga: Latvijas Universitātes Akadēmiskais apgāds.

20. gadsimta Latvijas vēsture 2. sēj. Neatkarīgā valsts 1918 – 1940. [The History of the 20th Century Latvia. 2nd Volume. Independent State 1918 – 1940]. 2003. Rīga: Latvijas vēstures institūta apgāds.

80.000 latu par pogu reklāmu [80,000 Lats for a Button Advertisement]. 1936. Rīts. No. 327, 26.11., 2.

2 Atpūta. 1935. No. 579: 12.

3 Sievietes Pasaule. 1937. No. 3, 01.02.

4 Rigasche Post. 1936. No. 52, 08.11.

5 Rigasche Post. 1936. No. 57, 06.12: 11.

6 Atpūta. 1938. No. 733, 18.11.; Atpūta. 1938. No. 729, 21.10.

7 Atpūta. 1936. No. 608, 26.06.: 21.

8 Для Вас: Еженед. ил. Журн. 1935. No. 30.

9 Atpūta. 1936. No. 608, 26.06: 24.

10 Rigasche Post. 1937. No. 8.

11 Для Вас: Еженед. ил. Журн. 1938. No. 41.

12 Atpūta. 1935. No. 580, 13. 12.: 19.

13 Atpūta. 1936. No. 596: 21.

14 Atpūta. 1936. No. 592, 06.03.: 9.

15 Atpūta. 1935. No. 578: 21

16 Atpūta. 1935. No. 581: 14.

17 Atpūta. 1935. No. 580, 13.12.: 27.

18 Jaunākās Ziņas. 1934. No. 208, 15.09.: 8.

19 https://picclick.de/BERLIN-Werbung-Anzeige-1936-ROTBART-MOND-EXTRA-162145779897.html (accessed 24.06.2022).

20 Atpūta. 1936. No. 628, 18.11: 23.

21 Atpūta. 1935. No. 569.

22 Brīvā Zeme. 1935. No. 247.

23 Atpūta. 1936. No. 605: 2.

24 Atpūta. 1935. No. 577, 22.11.: 19.

25 Atpūta. 1935. No. 581, 20.12.: 30.

26 Atpūta. 1935. No. 579: 12.

27 Rigasche Post. 1937. No. 8.

28 Atpūta. 1936. No. 608, 26.06.: 24.

29 Atpūta. 1936. No. 623: 19.

30 Atpūta. 1936. No. 632: 14.

31 Atpūta. 1936. No. 601, 08.05.: 13.

32 Atpūta. 1935. No. 580, 13.12.:19.

33 Rīts. 1936. Nr. 356.