Vertimo studijos eISSN 2424-3590

2025, vol. 18, pp. 161–176 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/VertStud.2025.18.9

Eriola Qafzezi

Fan S. Noli University

eqafzezi@unkorce.edu.al

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3874-8359

Abstract. This paper investigates how foregrounding is realized in Virginia Woolf’s The Mark on the Wall and its Albanian version Njolla në Mur (translated by Elvana Zaimi). Adopting a comparative stylistic approach, the study examines deviations at the graphological/phonological, lexicogrammatical, and semantic levels, identifying how these stylistic effects are preserved, transformed, or neutralized in translation. Close reading, supported by selective corpus insights, reveals a clear hierarchy of translatability: graphological and phonological foregrounding is the most vulnerable to change, lexicogrammatical markedness is largely maintained, and semantic foregrounding, especially metaphors and figurative patterns, shows the highest degree of preservation. The findings reveal that Woolf’s modernist style is partially reshaped in Albanian, with the translator prioritizing semantic fidelity and syntactic rhythm over sound-based or punctuation-driven effects. By analyzing a less studied language pair, the study contributes to a broader understanding of how modernist stylistic innovation travels across linguistic and cultural contexts.

Keywords: foregrounding, stylistics, translation, Virginia Woolf, deviation, Albanian.

Santrauka. Šiame straipsnyje nagrinėjama, kaip išryškinami žymėtieji teksto elementai (foregrounding) Virginios Woolf apsakymo „Žymė ant sienos“ (The Mark on the Wall) vertime į albanų kalbą Njolla në Mur (vertė Elvana Zaimi). Pasitelkiant lyginamąjį stilistinį požiūrį, tyrime analizuojami nukrypimai nuo normos grafologiniame ir fonologiniame, leksikogramatiniame ir semantiniame lygmenyse, siekiant nustatyti, kaip šie stilistiniai efektai vertime yra išlaikomi, transformuojami ar neutralizuojami. Atidusis skaitymas, papildytas pasirinktais tekstyno duomenimis, atskleidžia aiškią išverčiamumo hierarchiją: grafologinis ir fonologinis išryškinimas yra labiausiai paveikus pokyčiams, leksikogramatinis žymėtumas dažniausiai išlieka, o semantinis išryškinimas, ypač metaforos ir vaizdiniai raiškos modeliai, pasižymi didžiausiu išlaikymo laipsniu. Rezultatai rodo, kad Woolf modernistinis stilius albaniškame variante iš dalies persiformuoja, vertėjai pirmenybę teikiant semantiniam tikslumui ir sintaksiniam ritmui, o ne garsiniams ar skyrybos ženklų kuriamiems efektams. Autorei analizuojant mažiau tyrinėtą kalbų porą, šis tyrimas prisideda prie platesnio supratimo apie tai, kaip modernistinė stilistinė inovacija perteikiama skirtinguose kalbiniuose ir kultūriniuose kontekstuose.

Pagrindiniai žodžiai: išryškinimas, stilistika, vertimas, Virginia Woolf, nukrypimas, albanų kalba

_________

Copyright © 2025 Eriola Qafzezi. Published by Vilnius University Press

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Within stylistic theory, foregrounding has been proposed as an important mechanism for explaining how literary language departs from everyday norms, drawing attention to form, meaning, and perception. In particular, work within the Prague School tradition and subsequent stylistic frameworks has emphasized deviation and patterning as central to literary meaning-making. Yet the translation of foregrounding continues to raise questions about how stylistic markedness travels across languages. Virginia Woolf’s short story The Mark on the Wall, with its stream-of-consciousness narration, metaphoric layering, and syntactic deviation, offers a particularly rich site for exploring these issues. Although Woolf’s works have been studied extensively in major European languages such as Spanish, French, Italian, and German, research on her translation into less widely studied languages like Albanian remains rather limited. This leaves a clear gap in understanding how Woolf’s stylistic effects function outside dominant literary systems.

The Albanian translation by Elvana Zaimi provides an important opportunity to examine how foregrounded features, graphological, lexicogrammatical, and semantic, are negotiated across two typologically and culturally distinct languages. Albanian–English comparisons are valuable because they shed light on translation strategies in a linguistic context that has received insufficient scholarly attention, particularly with regard to modernist prose. Studying how Woolf’s experimental style is rendered in Albanian also contributes to widening the geographical and linguistic scope of Woolf translation studies.

Leech defines foregrounding in both formal and functional terms: “Formally, foregrounding is a deviation, or departure, from what is expected in the linguistic code or the social code expressed through language; functionally, it is a special effect or significance conveyed by that departure” (Leech 2008: 3). Foregrounding can be systematically identified at multiple levels, which Leech categorizes according to the main coding levels of linguistic analysis: (1) graphological/phonological, (2) lexicogrammatical, and (3) semantic (Leech 2008: 137).

Within the framework of our analysis, we follow Leech and Short’s (2007) understanding of Halliday’s three metafunctions of language, according to which language simultaneously fulfills ideational, interpersonal, and textual functions (Halliday 1971; Halliday and Hasan 1985), each of which relates to communicative needs:

1. Ideational function: it conveys a message about ‘reality’, about the world of experience, from the speaker to the hearer.

2. Interpersonal function: it must fit appropriately into a speech situation, fulfilling the particular social designs that the speaker has upon the hearer.

3. Textual function: it must be well constructed as an utterance or text, so as to serve the decoding needs of the hearer (Leech and Short 2007: 109).

Since the function of literature is primarily aesthetic, we are constantly seeking explanations of stylistic value, asking why one linguistic choice is made instead of another. This research considers not only the linguistic choices of the original author but also those of the translator, and how far the latter reflects or diverges from the stylistic design of the source text. Accordingly, the study is guided by the predominant research question of how foregrounding is realized in Virginia Woolf’s The Mark on the Wall and its Albanian translation Njolla në Mur. To address this question, two sub-questions are posed:

1. Does foregrounding appear at the same semantic, lexicogrammatical, and graphological/phonological levels in the target text and in the source text?

2. To what extent are the foregrounded elements preserved, transformed, or neutralized in translation?

As a concept, foregrounding presupposes individual style and creativity in language, often realized through innovativeness and a deliberate breaking away from norms and expectations. Innovativeness can be found in the writer, who experiments with linguistic form, but also in the reader, who must respond to and interpret the deviations encountered. Following the Prague School of poetics, the ‘poetic function’ of language has been characterized by its foregrounding or deautomatization of the linguistic code. This means that the aesthetic exploitation of language takes the form of surprising the reader into fresh awareness of, and sensitivity to, the linguistic medium which is normally taken for granted as an ‘automatized’ background of communication (Leech and Short 2007: 23).

For the purposes of this study, we are guided by Leech’s own analysis of The Mark on the Wall, where he illustrates examples of all three levels of foregrounding, here enriched by a cross-linguistic comparison with Albanian. In Style in Fiction, Leech and Short (2007: 105) point to graphological variation in aspects such as spelling, capitalization, hyphenation, italicization, and paragraphing. Phonological foregrounding includes consonant and vowel repetition (alliteration and assonance) with expressive function. At the lexicogrammatical level, foregrounding involves interactional features, minor sentences, right and left dislocation, progressive structures, parenthetical sentences, parataxis, and anacoluthon. At the semantic level, Leech demonstrates how color terms relate outer reality to inner imagination, and how verbs of motion describe life as a headlong journey, showing the interaction between physical and psychological experiences (Leech 2008: 139–143).

Foregrounding, however, cannot be separated from the reader’s reception of a text. Toolan emphasizes that stylistics is “always on the lookout for … pattern, repetition, recurrent structures, ungrammatical or ‘language-stretching’ structures, [and] large internal contrasts of content or presentation” (Toolan 1998/2010: 2). Such features often generate the reader’s first impressions of difficulty, surprise, or intensity. As Toolan further notes: “First impressions … often shape the closer language analysis that follows; they are claims that the more detailed attention will now seek to bolster, or adjust” (Toolan 1998/2010: 3). Foregrounding thus connects textual form with potential reception: stylistic devices become meaningful insofar as they are perceived as marked against linguistic norms. In a translational context, however, this does not imply equivalence of reader response, but rather comparability in the conditions of markedness created by the text within each linguistic system.

The interrelation between stylistics and translation further supports this study. Boase-Beier (2018: 196) rightly observes that in many areas central to Translation Studies it would be difficult to pursue meaningful research without at least some consideration of stylistics, particularly in literary translation. She further explains that work in stylistics and translation typically involves two perspectives: either what translation can tell us about style, or what stylistics can tell us about translation (Boase-Beier 2018: 199). We adopt her view that translation lies at the heart of stylistics not only historically, but also because it is a powerful tool for understanding and analyzing a text. Accordingly, the present study complements stylistic analysis of the source text with a translational analysis of the Albanian version, not in order to judge the translation, but to describe the changes introduced and how they affect the reading of the text, with particular reference to deviations.

Foregrounding, then, emerges as both a literary and a translational concern. It signals deviation from the norm, demanding active reader engagement, while at the same time challenging translators to decide whether to preserve or normalize deviations in the target language. For modernist texts such as Woolf’s The Mark on the Wall, whose style derives much of its force from deviation at different linguistic levels, the treatment of foregrounding in translation becomes decisive for how the work is received in a new linguistic and cultural context. Leech himself emphasizes this point: after his detailed analysis of Woolf’s interior monologue style in The Mark on the Wall, he concludes that “the richness and depth of this text will not be exhausted by one analysis, but will benefit from a number of alternative analyses” (Leech 2008: 177). In this perspective, the present study offers a cross-linguistic investigation, tracing stylistic peculiarities as they travel, or fail to travel, across languages.

The methodological approach adopted in this study is corpus-assisted stylistic analysis, combining the qualitative insights of close reading with the systematic tools of corpus linguistics. The analysis is based on two electronic corpora: the English source text, Virginia Woolf’s The Mark on the Wall (1919), and its Albanian translation, Njolla në Mur by Elvana Zaimi (2011). Both texts were first converted into plain-text format and then uploaded separately into Sketch Engine, a corpus management and analysis platform. This setup allowed for the use of frequency lists, concordances, and keyword comparisons to track patterns of frequency, repetition, and deviation in both corpora.

The decision to work with two monolingual corpora rather than a technically aligned parallel corpus reflects the focus of this study. Since the aim is to identify and compare foregrounding devices, it is sufficient to analyze each text independently and then accomplish a systematic cross-linguistic comparison between source and target texts. The analysis proceeded in three main steps:

The English text was examined for instances of stylistic deviation or markedness, following Leech’s tripartite categorization of foregrounding (Leech 2008: 137). Specific searches were conducted for:

Concordance searches and frequency lists in Sketch Engine supported the identification of candidate passages, with particular attention to repeated to deviation and marked style.

Each foregrounded passage identified in the English text was then aligned manually with the corresponding excerpt in the Albanian translation. This step ensured comparability between the two corpora at the level of specific examples but did not yet evaluate translational choices.

After manual alignment, each example was further analyzed to determine the translation strategy adopted: whether the foregrounded feature was preserved, transformed, or neutralized in the target text. These results were then interpreted across the three levels of foregrounding to trace recurring tendencies and broader patterns. The integration of Sketch Engine ensured methodological accuracy by providing traceable data on observed tendencies of deviation in both source and target texts, while the qualitative analysis foregrounded the interpretative act of translation analysis. This dual approach is particularly suited to the study of modernist prose, where meaning emerges not only from what is said but also from the way language resists norms through stylistic deviation.

In The mark on the Wall there are plenty of examples that reflect the inconsequential line of thought and contribute to Woolf’s unique lively style. Features such as the poetic use of conversational tone set Woolf apart from other prose writers. Such poetic qualities are worthy of investigating from a comparative stylistics’ perspective, illustrated with examples of foregrounding at different levels.

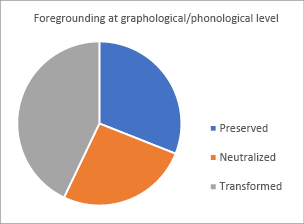

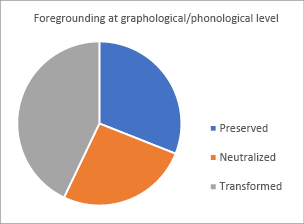

At the graphological and phonological level, the analysis identified 42 instances of foregrounding, out of which 18 were transformed, 13 preserved, and 11 neutralized; showing a clear tendency toward transformation. For example, em dashes, a device Woolf exploits to signal digression, are frequently rendered through commas or lexical alternatives, thus maintaining a sense of interruption but altering its visual form. Similarly, alliteration and assonance are largely neutralized in Albanian, where priority is given to semantic accuracy rather than to sound play. In contrast, punctuation-based foregrounding like ellipses is often preserved, which helps to mark hesitation and unfinished thought in Albanian as well. The data is visually represented in the following diagram:

Figure 1. Foregrounding at graphological/phonological level

Illustrative examples of each translation strategy can be found below.

Transformation:

(1a) There will be nothing but spaces of light and dark, intersected by thick stalks, and rather higher up perhaps, rose-shaped blots of an indistinct colour—dim pinks and blues—which will, as time goes on, become more definite, become—I don’t know what... (Woolf 1919: 3)

(1b) S’do të ketë asgjë përveç hapësirave me dritë dhe terr, të ndërprerë nga kërcej të trashë dhe ndoshta, nga njolla në formë trëndafili të një ngjyre të paqartë rozë e muzgët dhe blu, të cilat, me kalimin e kohës, bëhen më të mprehta, bëhen - nuk e di çfarë... (Woolf 2011: 28)

[There will be nothing except spaces of light and darkness, interrupted by thick stalks and perhaps by rose-shaped stains of an unclear colour dusky pink and blue, which, over time, become sharper, become - I don’t know what...]

Zaimi preserves Woolf’s syntactic drift and accumulating uncertainty, but transforms some of the graphological foregrounding. The punctuation system, especially the em dashes and spacing around hesitations, shifts toward Albanian norms, producing slightly different rhythmic effects. The translator retains the semantic indeterminacy and visual vagueness, yet the transformation of punctuation subtly alters the pacing and build-up of the “unfinished” perception that Woolf foregrounds.

Preservation:

(2a) How readily our thoughts swarm upon a new object, lifting it a little way, as ants carry a blade of straw so feverishly, and then leave it... (Woolf 1919: 1)

(2b) Sa shpejt hidhen mendimet tona mbi një objekt të ri, duke e ngritur një çast, ashtu si thneglat që ngrenë fije kashte aq dridhshëm, e pastaj e braktisin... (Woolf 2011: 26)

[How quickly our thoughts jump onto a new object, lifting it for a moment, just like ants that lift a blade of straw so tremulously, and then abandon it…]

This example shows strong preservation. Zaimi closely renders the metaphor, the dynamic movement, and the rhythmic pattern of Woolf’s sentence. The ellipsis is maintained, and the unusual simile involving ants is reproduced with very similar semantic and stylistic force. The translator succeeds in transferring both the image and the cognitive spontaneity that Woolf foregrounds, resulting in minimal loss of stylistic markedness.

Neutralization:

(3a) Wood is a pleasant thing to think about. It comes from a tree; and trees grow, and we don’t know how they grow. (Woolf 1919: 9)

(3b) Druri është një gjë e këndshme për t’u menduar. Ai vjen nga pema dhe pemët rriten; ne nuk e dimë si rriten. (Woolf 2011: 33)

[Wood is a pleasant thing to think about. It comes from the tree and trees grow; we do not know how they grow.]

Here the translation is faithful semantically but stylistically less foregrounded than the original. The simple rhythm and understated repetition in Woolf’s prose create a slightly whimsical tone, whereas the Albanian version sounds more straightforward and informational. The stylistic playfulness embedded in the recursive structure (trees grow… we don’t know how they grow) is softened, illustrating how foregrounding at phonological level is more prone to neutralization in translation.

These examples illustrate the broader pattern: while punctuation-based deviations (like ellipses) tend to be preserved, phonological effects (like alliteration and assonance) are frequently neutralized, and em dashes, or semicolons are often transformed into Albanian. This confirms that the degree of preservation strongly depends on the type of foregrounding device.

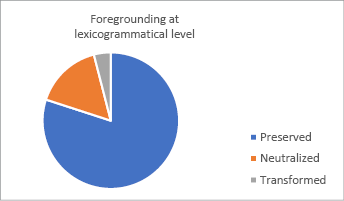

At the lexicogrammatical level, the analysis yielded 63 instances of foregrounding, of which 50 were preserved, 10 neutralized, and 3 transformed. The data show a strong tendency toward preservation (over three quarters of the cases), suggesting that Woolf’s lexicogrammatical markedness travels more successfully across languages than graphological or phonological ones. Only a handful of cases were transformed, while neutralization occurred in cases where the translation smoothed over marked syntax. The data is visually represented in the following diagram:

Figure 2. Foregrounding at lexicogrammatical level

Some examples follow:

Preservation

(4a) Yes, it must have been the wintertime, and we had just finished our tea, for I remember that I was smoking a cigarette when I looked up and saw the mark on the wall for the first time. (Woolf 1919: 1)

(4b) Po, duhet të ketë qenë dimër dhe ne sapo kishim pirë çajin, sepse mbaj mend që po pija një cigare kur hodha vështrimin lart dhe pashë për së pari njollën në mur. (Woolf 2011: 26)

[Yes, it must have been winter and we had just drunk our tea, because I remember that I was smoking a cigarette when I lifted my gaze and saw the mark on the wall for the first time.]

The translator preserves the temporal layering and memory-based sequencing of the original. The structure closely mirrors Woolf’s cumulative syntax, and the logical connectors (e.g., for I remember that…) are equivalently rendered. The lexicogrammatical foregrounding, built through the rhythmic unfolding of past events, is successfully maintained, reproducing the narrator’s introspective register and gently digressive tone.

Neutralization

(5a) To steady myself, let me catch hold of the first idea that passes... (Woolf 1919: 4)

(5b) Për t’u bërë e qëndrueshme, po kapem fort pas së parës ide që vjen... (Woolf 2011: 28)

[To become steady, I hold tightly to the first idea that comes…]

The translation conveys the core meaning but neutralizes some of the stylistic nuance of Woolf’s self-address (let me catch hold). The modal softness and the performative hesitation present in the English original are rendered as a more factual and impersonal construction in Albanian. This reduces the self-reflexive tone and slightly lowers the degree of foregrounding, neutralizing the original’s conversational immediacy.

Transformation

(6a) All the time I’m dressing up the figure of myself in my own mind, lovingly, stealthily, not openly adoring it for if I did that, I should catch myself out, and stretch my hand at once, for a book in self-protection. (Woolf 1919: 5)

(6b) Përherë përqas imazhin e vetes në mendjen time, me dashuri, me qëndrueshmëri, duke mos e admiruar haptazi, sepse nëse e bëj këtë, do ta kapja veten në gabim dhe do të shtrija menjëherë dorën në ndonjë libër për vetëmbrojtje. (Woolf 2011: 29)

[Always I align the image of myself in my mind, with love, with constancy, without admiring it openly, because if I do this, I would catch myself in a mistake and would immediately stretch out my hand to some book for self-protection.]

Here the translator restructures Woolf’s metaphorical phrase “dressing up the figure of myself” into a more abstract expression (përqas imazhin e vetes). This shifts the imagery from a tactile, visual metaphor to a conceptual one. While the internal reasoning and psychological tone are preserved, the richer layering of self-fashioning in the original is transformed into a more literal and less stylistically marked representation. The result maintains narrative clarity but alters the stylistic texture and the embodied quality of Woolf’s introspection. Furthermore, the paratactic chain of adverbs in the English original (“lovingly, stealthily, not openly”) is rendered in Albanian partly through prepositional phrases (“me dashuri, me qëndrueshmëri”) and a participial structure (“duke mos e admiruar haptazi”). This shift alters the rhythm and compresses the subtle nuances of secrecy present in the source text, resulting in a transformed foregrounding effect.

On the whole, we observe that lexicogrammatical foregrounding is the most stable across translation: rhetorical questions, minor sentences, dislocations, and paratactic structures are largely maintained. Neutralization occurs when English flexibility in imperatives or digressions is flattened, while transformation is rare and usually motivated by structural differences between the two languages.

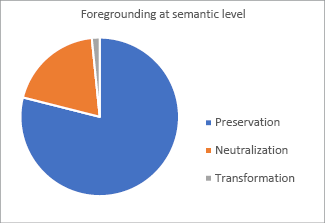

At the semantic level, the analysis identified 29 instances of foregrounding, of which 20 were preserved, 4 transformed, and 5 neutralized. These results show that preservation clearly dominates, confirming that figurative language and semantic markedness are more translatable than phonological play or syntactic experimentation. Nevertheless, some transformations and neutralizations occur, usually when metaphors or similes rely heavily on culture-specific imagery or stylistic nuance that does not transfer directly into Albanian. The data is visually represented in the following diagram:

Figure 3. Foregrounding at semantic level

Some examples follow:

Preservation

(7a) That is the sort of people they were very interesting people, and I think of them so often, in such queer places, because one will never see them again, never know what happened next. (Woolf 1919: 2)

(7b) Të tillë njerëz kanë qenë - njerëz tejet interesantë e i mendoj shumë shpesh, në ca vende të çuditshme, sepse askush nuk do t’i shohë më, askush nuk do të dijë kurrë ç’ndodhi më pas. (Woolf 2011: 26-27)

[Such people they were - extremely interesting people - and I think of them very often, in some strange places, because no one will see them again, no one will ever know what happened next.]

Zaimi preserves the emotive intensity and semantic layering of the original. The repetition, evaluative adjectives, and reflective tone are effectively transferred, retaining Woolf’s sense of nostalgic distance and unresolved narrative closure. The cumulative structure is reproduced faithfully, demonstrating that semantic foregrounding, especially evaluative and referential markedness, transfers well into Albanian.

Neutralization

(8a) Tall flowers with purple tassels to them perhaps. (Woolf 1919: 4)

(8b) Lule të larta me xhufka, ndoshta... (Woolf 2011: 29)

[Tall flowers with tufts, perhaps…]

The Albanian translation retains the basic referential meaning but neutralizes the stylistic vividness of purple tassels. The choice xhufka (eng. tufts) conveys shape but loses colour and textural specificity. Woolf’s sensorial precision is softened, and the image becomes less richly detailed.

Transformation

(9a) How readily our thoughts swarm upon a new object, lifting it a little way, as ants carry a blade of straw so feverishly, and then leave it... (Woolf 1919: 1)

(9b) Sa shpejt hidhen mendimet tona mbi një objekt të ri, duke e ngritur një çast, ashtu si thneglat që ngrenë fije kashte aq dridhshëm, e pastaj e braktisin... (Woolf 2011: 26)

[How quickly our thoughts jump onto a new object, lifting it for a moment, just like ants that lift a blade of straw so tremulously, and then abandon it…]

The semantic content is largely preserved, yet the rendering of swarm as hidhen (eng. jump) slightly shifts the conceptual metaphor from collective motion to a more individualised, instantaneous action. The transformation does not distort meaning but changes the conceptual dynamics of the image. Woolf’s metaphor of thoughts as a “swarm” loses some of its collective quality, illustrating how complex metaphors may be subtly reshaped depending on lexical availability and stylistic conventions in the target language, or, on the whole, translator’s choices.

Overall, the semantic level shows the strongest degree of preservation among all three levels of foregrounding. Woolf’s figurative language, particularly evaluative descriptions, emotional coloring, and introspective metaphors, transfers effectively into Albanian, largely because these semantic patterns rely on conceptual mappings that remain intact across languages. Neutralizations occur mainly where Woolf’s imagery is highly specific or sensorially rich, such as color, texture, or culturally embedded associations. Transformations tend to involve metaphors whose conceptual structure is adjusted subtly in translation, usually to maintain fluency or naturalness in Albanian. Despite these shifts, semantic foregrounding remains the most resilient category, supporting the broader claim that meaning-based stylistic deviation is more translatable than phonological or graphological effects.

Across the three levels of analysis, a clear hierarchy of translatability emerges. At the graphological and phonological level, preservation was the least frequent, with transformation and neutralization dominating, largely because sound effects and punctuation choices are closely tied to the conventions of the source language. By contrast, lexicogrammatical foregrounding proved far more stable: interactional features, rhetorical questions, dislocations, and parataxis were overwhelmingly preserved, with only occasional neutralization or transformation when Albanian syntactic norms required smoothing. At the semantic level, preservation was again dominant, with metaphors, similes, and binary contrasts generally traveling well across languages; transformation or neutralization appeared only when imagery relied on culturally specific associations or highly idiosyncratic phrasing. Taken together, the findings suggest that Woolf’s stylistic markedness is most vulnerable at the level of sound, more easily carried across at the level of lexis and grammar, and most securely retained in the realm of figurative meaning. This distribution shows the translator’s tendency to prioritize the transfer of semantic and structural effects while allowing greater flexibility, adaptation, or loss in cases where the original relies on language-specific phonological play or unconventional punctuation.

The corpus component of this study did not aim to replace close reading, but to support and enrich it by offering empirical evidence of recurring stylistic features. Frequency lists and concordance queries in Sketch Engine were useful for identifying lexicogrammatical patterns characteristic of Woolf’s style. For instance, perception verbs such as look, see, remember (Alb. shikoj, vështroj, kujtoj) emerged as high-frequency items in the English text and displayed comparable recurrence in the Albanian translation. This parallel confirmed that their function as markers of consciousness and narrative rhythm was consistently preserved. Likewise, color terms and basic connectors (and, but, so; Alb. dhe, por, prandaj) appeared prominently in both corpora, supporting the finding that semantic and lexicogrammatical foregrounding was largely maintained in translation.

Corpus evidence also reinforced the analysis of lexicogrammatical deviation. Concordance lines revealed repeated patterns of rhetorical questions, imperative constructions, and paratactic listings in the English text. Their frequency and distribution were broadly mirrored in the Albanian translation, although some instances were smoothed or restructured. By contrast, graphological and phonological foregrounding, such as alliteration, assonance, spacing, and punctuation-based deviation, could not be reliably captured through corpus tools, as these features lie outside the analytical range of frequency and concordance measures. Such phenomena were therefore identified exclusively through close reading. The combination of both methods proved productive: corpus analysis verified recurrent lexical and syntactic deviations, while manual inspection captured subtler graphological and phonological effects.

In this way, the corpus approach complements traditional stylistic analysis by distinguishing which deviations were systematically recurrent and therefore integral to Woolf’s style, and which were isolated or stylistically unique. This dual methodology ensured that the examples discussed in the previous sections were not unreliable but reflected broader textual patterns, thereby grounding the interpretive claims in empirical evidence. Given the relatively small size of the corpora, the corpus results were not statistically generalizable, but they nonetheless offered a useful confirmation of recurrent stylistic tendencies.

The results of the analysis demonstrate a hierarchy of translatability across the three levels of foregrounding. At the graphological and phonological level, preservation was less frequent compared to transformation. This phenomenon reflects the language-specific nature of sound patterns and punctuation, which resist straightforward transfer across English and Albanian. The instability of phonological effects confirms that the translator prioritized semantic clarity over sound play, a finding consistent with previous research on the translation of modernist prose. At the lexicogrammatical level, however, the balance shifts decisively toward preservation. Syntactic foregrounding through devices such as rhetorical questions, parataxis, and dislocations were largely retained, demonstrating that Albanian can successfully accommodate Woolf’s syntactic experimentation. There were still few cases of transformation or neutralization, which would suggest that while syntactic markedness is more portable than phonological play, it still requires occasional adaptation. Semantic foregrounding proved to be the most stable of all. Metaphors, similes, and binary contrasts were predominantly preserved, indicating that Woolf’s figurative language travels well into Albanian. Transformations and neutralizations were rare and often stylistically motivated. This stability identifies semantic markedness as a translatable stylistic resource.

The findings of this study align with existing scholarship on the translation of stylistic markedness, particularly with the view that foregrounding is variably translatable depending on the linguistic level involved (Boase-Beier 2018). The clear hierarchy identified here, greater preservation at the semantic level, partial preservation at the lexicogrammatical level, and higher vulnerability at the graphological and phonological levels, corresponds to patterns noted in previous studies, but has not previously been demonstrated in an Albanian context or with reference to Woolf’s modernist prose. This contributes new evidence to debates on stylistic equivalence and the constraints that target-language norms impose on experimental writing.

Taken together, the findings point to a consistent translational strategy: the Albanian version tends to prioritize meaning and syntactic rhythm over graphological/phonological effects. This reflects a pragmatic approach to rendering Woolf’s modernist style, balancing faithfulness to markedness within the constraints of the target language. The translator’s decisions go hand in hand with both the challenges and possibilities of transferring foregrounding devices at different levels: while some losses are inevitable, the overall rhythm and semantic depth of Woolf’s prose are largely preserved, ensuring that the Albanian reader still experiences the text’s experimental force.

Beyond its contribution to stylistics, the study also offers implications for translation pedagogy. Modernist prose, with its reliance on deviation, poses distinctive challenges for translation students, who must balance fidelity to stylistic patterning with the demands of natural expression in the target language. The findings may inform teaching practices by illustrating where such negotiations typically occur and by demonstrating the types of foregrounding most sensitive to translation shifts. They also serve to emphasize the necessity of training students to recognize not only meaning-based equivalence but also deviations that contribute to literary texture.

This study examined the translation of foregrounding devices in Virginia Woolf’s The Mark on the Wall from English into Albanian, distinguishing between graphological/phonological, lexicogrammatical, and semantic levels. The analysis showed that graphological and phonological foregrounding is the most likely to change, with transformation and neutralization outweighing preservation due to differences in punctuation conventions and sound patterns between the two languages. Lexicogrammatical foregrounding proved comparatively stable, with rhetorical questions, parataxis, and other syntactic dislocations largely maintained. At the semantic level, preservation dominated: metaphors, similes, and figurative contrasts transferred convincingly, confirming that meaning-based deviation is the most translatable category.

Selective corpus insights strengthened these findings by confirming the recurrence of key stylistic features, such as perception verbs, basic connectors, and rhetorical structures, across both texts, thereby supporting the qualitative analysis. At the same time, the study highlighted the methodological limits of corpus tools: graphological and phonological deviation could not be reliably captured computationally and required close reading. The combined use of corpus-assisted analysis and qualitative stylistic interpretation thus proved essential for capturing both recurrent patterns and subtle deviations.

On the whole, the findings indicate that the translator prioritized semantic fidelity and syntactic rhythm while allowing greater flexibility at the graphological and phonological levels. More broadly, the study contributes to the still limited scholarship on Woolf in underrepresented languages. Albanian remains largely absent from international discussions of modernist translation, and examining how Woolf’s stylistic principles function in this context broadens current understandings of her global reception. While the analysis points to comparable patterns of stylistic markedness in the source and target texts, no claim is made regarding equivalence of reader response. Reception effects remain contingent on cultural, literary, and linguistic norms, and can only be inferred indirectly through stylistic analysis rather than empirically confirmed.

Future work could investigate whether the same hierarchy of preservation, transformation, and neutralization appears in other Woolf stories or in translations into neighboring Balkan languages. A wider comparative perspective, across authors, texts, and linguistic systems, would help determine whether the patterns identified here reflect broader regional tendencies or language-specific effects, and further illuminate how experimental prose travels across linguistic and cultural borders.

Sources

Woolf, Virginia. 1919. The Mark on the Wall. Second Edition. Richmond: The Hogarth Press.

Woolf, Virginia. 2011. Njolla në mur [The Mark on the Wall]. Translated by Elvana Zaimi. Tirana: Skanderbeg Books.

Sketch Engine. (n.d.). Sketch Engine. Accessed June–September 2025. https://www.sketchengine.eu.

References

Boase-Beier, Jean. 2018. Stylistics and Translation. In The Routledge Handbook of Translation Studies and Linguistics, edited by Kirsten Malmkjær, London, New York. Routledge. 194–207.

Halliday, M. A. K. 1971. Linguistic Function and Literary Style: An Inquiry into the Language of William Golding’s The Inheritors. In Literary Style: A Symposium, edited by Seymour Chatman. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 330–365.

Halliday, M. A. K., and Ruqaiya Hasan. 1985. Language, Context, and Text: Aspects of Language in a Social-Semiotic Perspective. 2nd ed. Geelong: Deakin University Press.

Kilgarriff, Adam, Vít Baisa, Jan Bušta, Miloš Jakubíček, Vojtěch Kovář, Jan Michelfeit, Pavel Rychlý, and Vít Suchomel. 2014. The Sketch Engine: Ten Years On. Lexicography: Journal of Asialex 1 (1). 7–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40607-014-0009-9.

Leech, Geoffrey. 2008. Language in Literature: Style and Foregrounding. London: Pearson Longman.

Leech, Geoffrey, and Mick Short. 2007. Style in Fiction: A Linguistic Introduction to English Fictional Prose. 2nd ed. London: Pearson Education.

Toolan, Michael. 2010. Language in Literature: An Introduction to Stylistics. 2nd ed. London: Hodder Education.