Vertimo studijos eISSN 2424-3590

2025, vol. 18, pp. 51–67 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/VertStud.2025.18.3

Evelīna Ķiršakmene

University of Latvia

evelina.kirsakmene@lu.lv

https://orcid.org/0009-0008-3221-099X

Abstract: False friends are pairs of words in two or more languages that resemble each other in form (spelling, pronunciation, or both) but differ in meaning, often leading to misunderstandings or mistranslations. Unfortunately, like any other linguistic units, they are subject to change. The growing influence of English can be observed in many languages of the world, including Latvian. This has lead to the semantic broadening of some words previously considered strict and well-known false friends. The aim of this paper is to determine the actual use of five diachronically changing false friends in Latvian. A contrastive dictionary analysis is employed, along with excerpts from the press and a corpus. A survey of Latvian interpreters was also conducted to explore their experiences. The results provide evidence that some false friends are now predominantly used in Latvian with their English meaning, thus having partially become “true friends”, and highlight the need to assess the current usage of other false friends.

Keywords: false friends, interference, semantic broadening, diachronic change, interpreting

Santrauka. Netikrieji vertėjo draugai – tai dviejų ar daugiau kalbų žodžiai, panašūs savo forma, bet besiskiriantys savo reikšmėmis ir dėl savo garsinio ar grafinio panašumo klaidinantys vertėjus, nes gali būti suprasti kaip turį tą pačią reikšmę ir esą atitikmenys. Deja, kaip ir kiti kalbos vienetai, jie kinta. Didėjantis anglų kalbos poveikis pastebimas daugelyje pasaulio kalbų, įskaitant latvių. Dėl to kai kurių anksčiau aiškiais ir gerai žinomais netikraisiais draugais laikytų žodžių reikšmės išsiplėtė. Šio straipsnio tikslas – nustatyti penkių diachroniškai besikeičiančių netikrųjų draugų faktinį vartojimą latvių kalboje. Taikoma gretinamoji žodynų analizė, remiamasi ir pavyzdžiais iš spaudos ir tekstyno. Be to, atlikta latvių kalbos vertėjų apklausa, siekiant išsiaiškinti jų patirtį. Rezultatai rodo, kad kai kurie netikrieji draugai dabar latvių kalboje dažniausiai vartojami ta reikšme, kurią turi anglų kalboje, taigi iš dalies tapo „tikraisiais draugais“, taip pat išryškėja poreikis įvertinti kitų netikrųjų draugų dabartinę vartoseną.

Pagrindiniai žodžiai: netikrieji draugai, interferencija, semantinis išsiplėtimas, diachroninis pokytis, vertimas žodžiu

_________

Copyright © 2025 Evelīna Ķiršakmene. Published by Vilnius University Press

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

The goal of the present paper is to address some cases of diachronically changing false friends in Latvian: it is achieved by looking at them in monolingual dictionaries, analysing their use in the press and the Balanced Corpus of Modern Latvian (hereinafter – LVK) (Online 1), and by conducting a survey with Latvian interpreters. A brief overview of false friends will be presented to outline the main information concerning them. As defined in the ‘Dictionary of Translation Studies’, the term ‘false friends’ describes “items which have the same or very similar form but different meanings, and which consequently give rise to difficulties in translation (and indeed interlingual communication in general)” (Shuttleworth 2014: 57-58). False friends, in fact, could be regarded in a psycholinguistic category: “when dealing with false friends, one cannot ignore the foreign language learner, speaker, translator or interpreter” (Kasparė 2012: 67).

There are different classifications of false friends, but the main categories include chance false friends (without any etymological links) and semantic false friends, which can be further sorted into full semantic and partial semantic false friends (Chamizo-Domínguez 2012: 4-7). In this paper they will be respectively called monosemantic and polysemantic false friends. It is thought that partial false friends cause most difficulties and issues for overall comprehension since these pairs of words “are very close to each other and often share some senses while they differ in others”, and they are not so straightforward as monosemantic false friends (Kasparė 2012: 72).

False friends are the consequence of language interference. If previously the Latvian language was strongly influenced by mainly German and Russian among other languages, now English dominates in public, official and international communication (Baldunčiks 2005: 56). It is stated that “from the end of the 20th century, English terminology has been invading the Latvian language”, which skyrocketed after Latvia joined the European Union in 2004 (Skujiņa and Ilziņa 2011: 43; transl. by E. Ķ. hereinafter). Others have also noted the increased influence of the English language: “the translation scene is thus characterized by the dominant role of English as a source language, by an enormous growth in the translated information volume and a major shift from expressive (fiction) texts to appellative and informative texts” (Veisbergs 2006b: 152). This has led to massive borrowing from the English language into Latvian. Occasionally, new borrowings lead to the false friend phenomenon.

Stankevičienė (2005) conducted a highly detailed study of false friends in the English-Lithuanian language pair. She concluded that many false friends in Lithuanian were loans from Greek or Latin origin, “which are more or less isolated in the lexical system of the Lithuanian language from both a formal and semantic point of view” (Stankevičienė 2005: 528). The words taken up from English have limited possibilities in word-formation to integrate the target language fully; whereas in English, these words have “full grammatical and word-building paradigm” (Stankevičienė 2005: 528). Such findings in Lithuanian are relevant also for Latvian since both languages are undergoing similar processes of borrowing from English. Baldunčiks highlights that English-Latvian false friends are mostly internationalisms from Greek or Latin, or loans from modern languages where these words were coined on the basis of these languages (Baldunčiks 2005: 58).

Due to social media, which is now offering the possibility of crowdsourced translation, hybrid syntactic constructions, calques and false friends, lexical and grammatical oddities are now a part of the vocabulary of a large category of speakers: “their oddity and inappropriateness are now beginning to pass unnoticed, as more and more speakers are treating them as legitimate linguistic forms” (Bors and Ignat 2019: 216). Kasparė points out that the appearance of false friends can be explained by various phenomena: “interference of the native language, usual carelessness, convenience, search for psychical comfort and cognitive simplification” (Kasparė 2012: 72).

Most studies on false friends in Latvian have been carried out in the English-Latvian language combination (Veisbergs 1998; Žīgure 2004; Baldunčiks 2005), but there have also been studies in French-Latvian (Bankavs 1989), Lithuanian-Latvian (Sarkanis 2024), and other languages.

False friends are most often regarded in the aspect of translation and language learning. They can account for serious mistakes, distortion of meaning, as well as amusing sentences: with their help, literary, humoristic and cognitive effects can be achieved (Chamizo-Domínguez 2012: 29).

Kasparė notes that false friends are significant not only because they present themselves in ordinary situations and are frequently used words, but also because of “the importance of clear understanding and exact translation in the scientific, political, commercial fields as well as in many others” (Kasparė 2012: 68). Stankevičienė points out that because of the recent rise of pop culture from the West, “translation problems caused by lexical pseudo-equivalents or false friends are more numerous than ever” in Lithuanian and English (Stankevičienė 2005: 521). Considering the increasing influence of the English language, “the main source of language errors seem to be rough, hasty translation, as well as, increasingly in the past decade, automatic (or machine) translation” (Bors and Ignat 2019: 214).

One might expect that bilingual dictionaries would clarify these dangerous word pairs, yet many have noticed inconsistencies when dealing with false friends: “even when a bilingual dictionary has the correct translation, it rarely contained a note to warn the user of possible misunderstanding” (Hill 1982: i). Furthermore, errors can arise because in some language combinations false friends have not yet been studied extensively: “until recently the study of false friends between Estonian and English has been a neglected area. [..] it comes as no surprise that the existing bilingual dictionaries often provide erroneous and confusing information” (Veldi 2006: 171). Therefore, in this paper monolingual dictionaries in each language pair will be used to find out the officially recognised meaning of the word in discussion.

In this paper, diachronically evolving false friends will be regarded from the point of view of interpreting. Interpreting is specific due to time constraints that do not allow for prolonged exploration of specific terms and their meanings, but “things become really difficult when the interpreter does not understand the source text unit and cannot guess it from the context either” (Veisbergs 2006a: 1222).

Traditional classification of semantic change involves specialization or narrowing and generalization or widening (Broz 2006: 205). Differences in false friends’ semantics have been remarked already: semantic borrowing can be observed when old Latvian words or internationalisms “acquire new meanings because of the polysemy of their English counterparts [..] as a result, many false friends of the Latvian-English language pair have become ‘true friends’ in the Latvian-English dichotomy” (Veisbergs 2006b: 155-156).

Usually, semantics was regarded as a “haphazard process by which the meaning of the word can go in any direction” (Broz 2006: 203), as is the general idea behind traditional linguistics. This idea is also echoed in the work of Mona Baker: “once a word or expression is borrowed into a language, we cannot predict or control its development or the additional meaning it might or might not take on” (Baker 1992: 25). Hence, no patterns were investigated in the research regarding false friends, and “they have usually been approached by cataloguing them” (Broz 2006: 203). It is impossible to list all false friends in a specific language pair due to the “lack of generally agreed criteria for defining them and the way in which linguistic change leads to the emergence of the new pseudo-equivalents and disappearance of the old ones” (Stankevičienė 2005: 528-529).

Research on false friends is rarely conducted from the diachronic point of view rather than synchronic (Chamizo-Domínguez 2012: xiii). The ever-changing nature of false friends is both a fascinating and challenging aspect in their research. Polysemantic words appear naturally in any language; however, they can have a negative impact in translation as they can “introduce notional misunderstanding and jeopardize the accuracy and relevance to the source text” (Skujiņa and Ilziņa 2011: 44). In consequence, the semantic broadening of false friends could lead to a possible lack of understanding in the translation process.

We will be looking at five examples of English-Latvian false friends which show signs of semantic broadening by becoming polysemous words in Latvian, namely dekāde, diēta, fikcija, afēra and virāls. They have been chosen from the author’s personal corpus of false friends in English and Latvian, which is still being compiled and contains approximately 350 words. They have been selected for their diachronically diverging meanings; the analysed examples of false friends are subjectively selected and do not represent universal tendencies enveloping all pairs of false friends.

A triangulation of research methods is applied, consisting of contrastive analysis of different definitions and explanations provided in Latvian and English monolingual dictionaries. Two Latvian monolingual dictionaries are used: the previously mentioned MLVV (Online 2) and Tēzaurs (Online 4), and one English monolingual dictionary: English Learner’s Dictionaries (Online 3). Examples of attested word use are analysed from the corpus LVK (Online 1) and Latvian periodicals (Online 5). Lastly, a survey was conducted with Latvian interpreters to determine whether they have noticed diachronic changes in these false friends in their work. This method was chosen because “often interpreters are the first people of a language community that confront new notions and new terms in the source language that do not exist in the target (usually the interpreter’s native) language” (Veisbergs 2006a: 1223-1224).

The Balanced Corpus of Modern Latvian was chosen for this study because it is the most recent edition of a balanced corpus in Latvian, thus providing more accurate and up-to-date information. In addition to that, it covers a wide range of different types of texts (press, original and translated literature, scientific texts, legislative acts, texts from Wikipedia, National parliament transcripts and subtitles), therefore providing a global insight into the actual language use. A possible limitation of the study that needs to be considered is the limited number of questionnaire participants (in total 33), as well as their specific category as highly skilled language professionals. They are interpreters whose primary working language is Latvian, and they currently work either in Latvian translation and interpreting agencies or are accredited conference interpreters working at the EU institutions. The survey began with two background questions to determine years of experience and working languages. Most of them have worked as interpreters for a period of 11-20 years (15 respondents, or approximately 47 percent) or 21-30 years (12 respondents, or 36 percent). All interpreters have mentioned English as their working language with other languages like French (14 respondents), German (14), Russian (10), Italian (3), Spanish (2), and others. Ten questions followed (two for each meaning of the false friend) to determine the interpreters’ view and experience on the previously mentioned five false friends. Answer options were categorized in Likert scale with 1 being ‘very rarely’ and 5 ‘very frequently’. This approach was chosen to determine nuances in word use. The questionnaire ended with three closing questions to assess participants’ opinion, with the option of adding their own comments and examples (see Appendix).

MLVV provides one meaning: “a period of ten days”. In Tēzaurs, two meanings appear: a ten-day and a ten-year period. The original English meaning, as stated in OLD, is a period of ten years. The reason the meaning is different in Latvian is that here it is a loan from the French décade (10 days), which comes from Greek (Online 2). In contrast, the English word has an identical Greek origin, but starting from the 17th century, it developed the meaning of “ten days” (Online 3).

LVK presents 46 concordances. 27 of them, or 58 percent, are with the meaning of ‘ten years’:

1) dekādes brīnumbērns [the wunderkind of the decade],

2) pēdējās desmitgadēs Latvijā vērojama pastāvīga depopulācija [during the last decades, there has been a constant depopulation in Latvia],

3) pēdējās dekādēs starptautiskā migrācija ir kļuvusi par [during the last decades international migration has become],

4) trīs dekādes ilgajai karjerai [a three decades long career].

In periodicals, the word appears almost equally often with both meanings: ‘ten days’ and ‘ten years’. Some examples of the non-official meaning (which is not mentioned in Latvian dictionaries) can be seen below:

5) audzināšanas metodes, kuras pasaulē lieto jau dekādēm [upbringing methods that have been used in the world for decades] (Mans Mazais, 01.01.2023),

6) pēc piecgades būs pavisam traģiski, pēc dekādes var iznākt slēgt iestādi vai uzņēmumu [after five years it will be tragic, after a decade it could be the end of an institution or a company] (Diena, 27.09.2024),

7) šī dalīšanās ēdienu prakse īpašu popularitāti pasaulē guvusi tieši pēdējā dekādē [this practice of sharing meals gained its worldwide popularity particularly in the last decade] (Una, 01.11.2024).

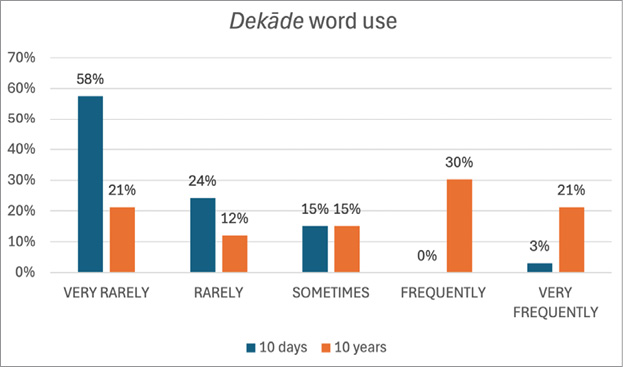

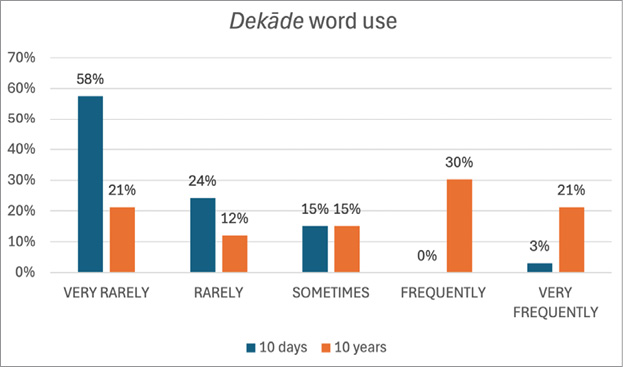

In the questionnaire, more than half of the interpreters stated that they have experienced the word dekāde with its meaning ‘ten days’ very rarely; the majority responded that the word is used with the meaning of ‘ten years’ either frequently or very frequently. The visualization of the obtained results can be seen below:

Graph 1. Survey’s responses for the word dekāde.

In the comments section, some interpreters mentioned that the word dekāde is increasingly being used with the latter meaning: “you can often hear it in spoken language, on the radio, and in advertisements” and “it’s a pity that everyone has forgotten that dekāde in Latvian means ‘ten days’.” The correlation calculated between the two answers was weakly negative at –0,29.

In MLVV, two meanings are mentioned: “specific dietary restrictions (e.g. for losing excess weight)” and “a set of dishes, a menu” (Online 2). However, in Tēzaurs only the first meaning appears. In OLD: “the food and drink that you eat regularly”, “limited variety or amount of food that you eat for medical reasons or because you want to lose weight”, and “a large amount of a limited range of activities” (Online 3).

In the corpus, 390 concordances showed up, out of which six were mentions of diēta with its more general meaning:

8) bieži vien problēmu izdodas atrisināt, izmainot diētu, iesakot vingrinājumus un uztura bagātinātājus [the problem is often solved by changing your diet, recommending exercise and food supplements],

9) būtiski samazināt gāzu emisijas var izmaiņas mūsu diētā [changes in our diet can significantly decrease gas emissions],

10) ir vērtīga ikdienas diētas sastāvdaļa [is an important part of our everyday diet].

The word diēta is first mentioned in the Latvian press in 1864; it mostly appears with the meaning ‘food and drink restriction’ in such collocations as drakoniska diēta [draconian diet], ieturēt diētu [to be on a diet], and others. There are also more recent uses that imply a broader sense of the word:

11) veselīga diēta un liekā svara samazināšana [a healthy diet and weight loss] (Veselība: populārzinātnisks žurnāls ģimenei, Nr. 2, 01.02.2020),

12) mūsdienu rietumnieku diētā bieži šī attiecība ir 1:15 [in modern Western diets, the ratio is often 1:15] (Una, Nr. 5, 01.05.2020),

13) es kā imunoloģe īpaši par dzīvesveida un diētas korekciju ieteiktu padomāt [as an immunologist I would suggest considering lifestyle and diet changes] (Tava imunitāte. Veselība speciālizdevums, Nr. 1, 01.05.2020).

In the survey, 19 participants (approximately 57 percent) responded that they encountered the word with the meaning of ‘food restriction’ very frequently, and 9 participants chose the option frequently. Therefore, the mode and median for this question are both very frequently. Yet for the question whether they have encountered the word diēta being used with the meaning ‘overall consumption of food’, the most frequently chosen answer (the mode) was very rarely, while the median was rarely. There was little to no correlation between the results of the two questions.

In MLVV and Tēzaurs, only one meaning is provided – the meaning ‘invention/figment’. However, OLD lists two meanings: the first is “a type of literature”, and the second corresponds to the Latvian meaning, “invention”. Previously, this was a classic case of a polysemantic false friend, since only one meaning existed in Latvian, while there were two in English.

In the corpus, this word appears only 17 times and in all instances it is used with the meaning ‘invention’. The word appears for the first time in the Latvian press in 1915 with the meaning of something fictitious and invented. Today, the word sometimes appears in contexts where it is used as it would be in English:

14) Ņujorkā sapulcēto sabiedrību uzrunāja zinātniskās fikcijas meistars Artūrs S. Klārks [Arthur C. Clarke, master of science fiction, addressed the assembled audience in New York] (Laiks, Nr. 15, 14.04.2001),

15) nupat pārlasīju vienu zinātnes fikcijas grāmatu [I just reread a science fiction book] (Ievas Veselība, 13.12.2024).

The survey responses indicate that interpreters most often hear the word fikcija used in the sense of ‘something invented’: 11 participants chose the option frequently, 10 very frequently, and 6 sometimes. When asked about the same word being used with the meaning ‘a type of literature’, 28 participants (84 percent) chose the option very rarely. Little to no correlation was found between the two responses.

In MLVV, only one meaning is noted: that of a speculative affair or shady transaction. Tēzaurs, however, provides the second, colloquial meaning: love affair. In OLD, the word has six distinct meanings: public or political activities, event, relationship, private business, a thing someone carries responsibility for, and an object. Therefore, this is a case of a polysemantic false friend with several meanings in English but only one official meaning in Latvian.

In the corpus, afēra is used with the meaning ‘romantic affair’ in 41 out of 558 attested occurrences, which constitutes approximately 7 percent. Examples of such collocations include: afēras un darba romāniņi [affairs and workplace romances], veidot mīlas afēru [to have a love affair], traka, kaislīga afēra [crazy, passionate love affair].

It is likely that afēra entered Latvian through German, as newspapers from 1870 use the word with its German spelling. At the end of the 19th century, it appears increasingly often in the press in the collocation Dreifusa afēra [Dreyfus affair], which is a calque from French. Today, some uses of afēra as ‘love affair’ can be observed, but they remain infrequent:

16) bet afēru ar skaisto un jauno Marļu miljonārs pat nemēģināja slēpt [but the millionaire didn’t even try to hide his affair with the beautiful and young Marla] (Ieva, Nr. 5, 01.02.2017),

17) sižets vēstī par viņas mīlas afērām ar dabasbērnu [the plot is about her love affairs with the child of the nature] (Santa, Nr. 4, 01.04.2019),

18) visu šo afēru var izvērst ilgākā seriālā vairāku dienu garumā – sākt ar valšķīgu flirtu, tad ar pāris solījumiem [the whole affair could be developed into a series overall several days – start with tricksy flirtation, then a few promises] (Ieva, Nr. 16, 17.04.2019).

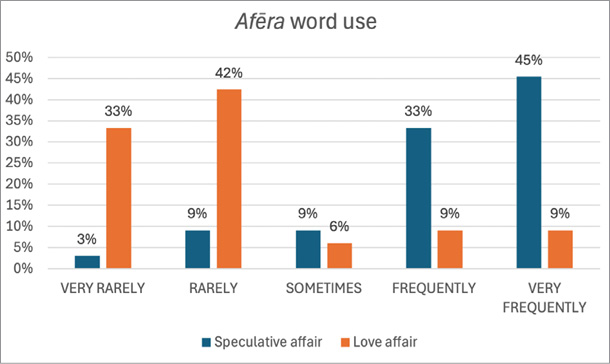

The survey results indicate that 15 participants reported encountering the word afēra with the meaning ‘a fraudulent affair’ very frequently, and 11 reported frequently. For the meaning ‘love affair’, 14 participants stated that they rarely encounter the word in this sense, and 11 stated very rarely. A weak positive correlation was calculated between the two sets of responses. The results are shown in the graph below.

Graph 2. Survey’s responses for the word afēra.

While nominated as one of the worst words of the year 2024 in a Latvian user poll due to its increased use as its English counterpart (Online 6), MLVV does not have an entry for virāls, whereas Tēzaurs provides: “virus-related; caused by viruses”. OLD lists two meanings: “like or caused by a virus” and “used to describe a piece of information, a video, an image, etc. that is sent rapidly over the internet and seen by large numbers of people within a short time”.

In the corpus, it is evident that virāls appears in Latvian with the latter meaning provided by OLD starting from 2014-2015; previously, it was mentioned only in relation to medicine. Out of 72 occurrences, 34 – or almost half – were used with the meaning of a popular sensation on the internet, with collocations such as virāla reklāmas kampaņa [viral advertisement campaign], virāla sensācija [viral sensation], and virāls hits [viral hit], among others.

In the periodicals, the situation is similar to what can be observed in the corpus. Since 2020, a new collocation has appeared in Latvian: virāla zvaigzne [a viral star].

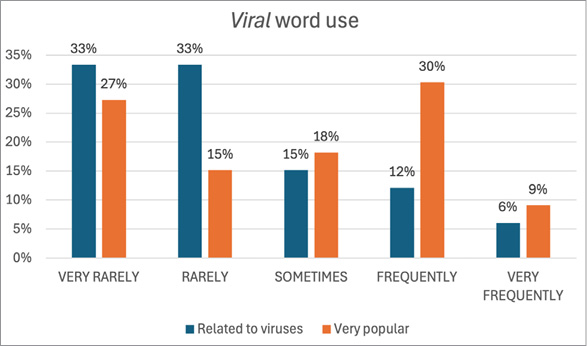

In the survey, two modes were determined for the answer option ‘related to viruses’: 11 interpreters chose very rarely and 11 chose rarely. For the second question concerning the word virāls, 10 participants stated that they frequently encounter it with the meaning ‘very popular’, whereas 9 responded that they see this meaning very rarely. The mean for the sense ‘related to viruses’ is rarely, while for the second sense it is sometimes. This suggests that the use of this word is variable, and it can appear in both uses. A weak positive correlation exists between the responses to the two questions.

Graph 3. Survey’s responses for the word virāls.

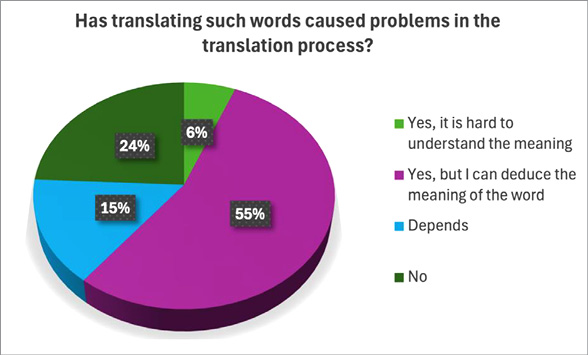

Three more questions followed in the third part of the questionnaire. For the 13th question, 12 participants responded positively when asked whether they had noticed these false friends being used increasingly with their English meanings, while 11 participants responded sometimes. For the 14th question, more than half of the participants reported encountering problems with diachronically changing false friends, whereas almost a quarter of them stated that they had not experienced any issues. These results are presented below:

Graph 4. Responses to the 14th question of the survey.

For the 15th question, “Have you encountered such examples when translating from languages other than English?”, many examples were provided. These include ekspertīze and intelligence, which are used with their English meanings, biljons [billion] which is sometimes used instead of the correct word in Latvian miljards, and konsekvence, which is sometimes used with its English meaning, “consequences”. One participant noted that such mistakes are more likely to occur when interpreting in retour, and that words with Latin roots that exist in both French and Spanish cause many problems. Another participant mentioned the adjective patētisks, which does not correspond to pathetic in English or pathétique in French. Some examples in the English-German language pair were also mentioned, such as actual-aktuell, eventually-eventuell.

In the comments section, some participants stated that the examples mentioned in the questionnaire were characteristic of, or more pertinent to, the younger generation. To examine this point, correlations were calculated between the number of years worked in this field and the responses to each question. In some cases, weak positive correlation was found (for the word dekāde as in ‘ten days’, diēta as ‘restriction of food’, and fikcija as ‘something invented’). In these instances, the weak positive correlation applies to the traditional, official meanings of these words. This suggests that interpreters with longer work experience tend to understand these words in their traditional sense, and notice alternative usages less frequently.

Another extensive comment at the end noted that problems with false friends often occur when interpreters are tired, as it can seem easier to simply add Latvian endings to source-language words rather than think of a better equivalent. The author of the comment admitted to making such mistakes, for example saying mākslīgā inteliģence when the speaker said intelligence artificielle in French (in this case, the standard Latvian collocation is mākslīgais intelekts). The commenter also reported hearing colleagues translate civil war as civilais karš in Latvian, whereas it is usually rendered as pilsoņu karš. However, the person emphasized that outside the booth, every interpreter knows the correct meanings of such false friends, and that these errors stem from stress and overload.

In recent decades, some former English-Latvian false friends have tended to adapt their meanings to the English counterparts, thus dissolving the strict boundaries of the notion of false friends in these word pairs. In this paper, five false friends were analysed from the point of view of their official meanings in monolingual dictionaries, their use in the corpus of modern Latvian and press, and from the interpreters’ perspective. The results indicate that the nouns in Latvian dekāde and virāls are now increasingly being used with the meanings their counterparts have in English, even though the definition in Latvian monolingual dictionaries states only one meaning. For the three other examples, no clear evidence was established that the English meaning of the word is dominating; however, some examples can be found in the corpus and the press. Thus, this paper provides an essential insight into the semantic development of certain false friends. Interpreters have had experience with diachronic false friends, and they generally seem to cope with the meaning differentiation. Further studies are needed to provide thorough conclusions about diachronically changing false friends due to English-language influence.

References

Baker, Mona. 1992. In other words. Routledge.

Baldunčiks, Juris. 2005. Tulkotāja viltusdraugu problēma: no vārdiem pie darbiem [The translator’s issue of false friends: from words to deeds]. In Valodas prakse: vērojumi un ieteikumi, 1. 56–64.

Bankavs, Andrejs. 1989. Les faux amis du traducteur franco-lettons [Translator’s French-Latvian false friends]. Rīga: P. Stučkas LVU.

Bors, Monica, and Anca Ignat. 2019. Facebookland: The bizarro-linguistic world. Alea: Estudos Neolatinos, 21 (3). 211–226. https://doi.org/10.1590/1517-106x/2019213211226.

Broz, Vlatko. 2006. Diachronic investigations of false friends. Suvremena lingvistika, 34 (66). 199–222.

Chamizo-Domínguez, Pedro J. 2012. Semantis and Pragmatics of False Friends. New York: Routledge.

Granger, Sylviane, and Helen Swallow. 1988. False friends: a kaleidoscope of translation difficulties. Langage et l’Homme, 23 (2). 108–120.

Hill, Robert J. 1982. A dictionary of false friends. London and Basingstoke: The Macmillan Press Ltd.

Kasparė, Laimutė. 2012. English-Lithuanian interpreter’s false friends: Psycholinguistic issues. Filologija (17). 67–77.

Sabino, Marilei Amadeu. 2016. False cognates and deceptive cognates: issues to build specific dictionaries. In Proceedings of the 17th EURALEX International Congress, edited by Tinatin Margalitadze and George Meladze. Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi University Press. 746–755.

Sarkanis, Alberts. 2024. Viltusdraugi un pusdraugi latviešu un lietuviešu valodā [False friends and half-friends in Latvian and Lithuanian]. Linguistica Lettica. Veltījumkrājums Laimutei Balodei. Rīga: SIA “Drukātava”. 244–273.

Shuttleworth, Marc. 2014. Dictionary of Translation Studies. Routledge.

Skujiņa, Valentīna, and Ilze Irēna Ilziņa. 2011. The development of Latvian terminology under the impact of translation. Terminologija 18. 43–50.

Stankevičienė, Laimutė. 2005. English-Lithuanian Lexical Pseudo-Equivalents. A Lexicographical Aspect. In Symposium on Lexicography XI, edited by Henrik Gottlieb, Jens Erik Mogensen and Arne Zettersten. Berlin, Boston: Max Niemeyer Verlag. 521–530. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110928310.521.

Veisbergs, Andrejs. 1998. False friends in Latvian, dictionaries, current problems. Linguistica Lettica 3. 12–26.

Veisbergs, Andrejs. 2006a. Dictionaries and interpreters. In Proceedings of the 12th EURALEX International Congress, edited by Elisa Corino, Carla Marello and Cristina Onesti. Torino: Edizioni dell’Orso. 1219–1224.

Veisbergs, Andrejs. 2006b. East wind, West wind in translation (What the English tsunami has brought to Latvian). In Pragmatic aspects of translation. Proceedings of the fourth Riga International Symposium, edited by Andrejs Veisbergs. Rīga: SIA JUMI. 148–168.

Veldi, Enn. 2006. English-Estonian Dictionary of False Friends: Why was this Dictionary Needed?. In Pragmatic Aspects of Translation: Proceedings of the Fourth Riga International Symposium, edited by Andrejs Veisbergs. Rīga: SIA JUMI. 169–181.

Žīgure, Veneta. 2004. Dažas viltus draugu radītās problēmas praktisko iemaņu apguves procesā tulkošanā [Problems of false friends in acquisition of practical translation skills]. Contrastive and Applied Linguistics, XII. 191–197.

Internet sources:

[Online 1] Available from LVK2022. https://korpuss.lv/en/id/LVK2022. (Accessed 15 January 2025).

[Online 2] Available from MLVV. https://mlvv.tezaurs.lv/ (Accessed 22 January 2025).

[Online 3] Available from Oxford Learner’s Dictionaries. https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com. (Accessed 22 January 2025).

[Online 4] Available from Tēzaurs. https://tezaurs.lv/. (Accessed 23 January 2025).

[Online 5] Available from Latvian National digital library collection “Periodika”. https://periodika.lndb.lv/. (Accessed 13 January 2025).

[Online 6] Available from “2024. gada vārds – “apritīgs”, gada nevārds – “grafisks”. https://www.lsm.lv/raksts/kultura/kulturtelpa/27.01.2025-2024-gada-vards-apritigs-gada-nevards-grafisks.a585325/. (Accessed 27 January 2025).

Acknowledgment

The publication is financed by the “Internal and External Consolidation of the University of Latvia” of the second round of the Consolidation and Governance Change Implementation Grants within Investment 5.2.1.1.i “Research, Development and Consolidation Grants” under Reform 5.2.1.r “Higher Education and Science Excellence and Governance Reform” of Reform and Investment Strand 5.2 of the Latvian Recovery and Resilience Mechanism Plan “Ensuring Change in the Governance Model of Higher Education Institutions”

First part of the questionnaire.

1. Cik liels ir Jūsu tulka darba stāžs? (How long have you been working as an interpreter?) Single choice question.

• 1-10 gadi (1-10 years)

• 11-20 gadi (11-20 years)

• 21-30 gadi (21-30 years)

• 31-40 gadi (31-40 years)

• Cits (Other)

2. No kādām valodām ikdienā tulkojat mutiski? (Which ones are your working languages in interpretation?) Multiple choice question.

• Angļu (English)

• Franču (French)

• Vācu (German)

• Itāļu (Italian)

• Spāņu (Spanish)

• Krievu (Russian)

• Cits (Other)

Second part of the questionnaire. Single choice questions.

3. Cik bieži saskaraties ar vārda dekāde lietojumu latviešu valodā ar nozīmi ‘10 dienas’? (How often do you encounter the word dekāde in Latvian with the meaning ‘10 days’?)

|

Answer type |

Very rarely |

Rarely |

Sometimes |

Frequently |

Very frequently |

|

Scale |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

4. Cik bieži saskaraties ar vārda dekāde lietojumu latviešu valodā ar nozīmi ‘10 gadi’? (How often do you encounter the word dekāde in Latvian with the meaning ‘10 years’?)

|

Answer type |

Very rarely |

Rarely |

Sometimes |

Frequently |

Very frequently |

|

Scale |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

5. Cik bieži saskaraties ar vārda diēta lietojumu latviešu valodā ar nozīmi ‘uztura ierobežošana konkrēta mērķa dēļ’? (How often do you encounter the word diet in Latvian with the meaning ‘restricting food intake for a specific purpose’?)

|

Answer type |

Very rarely |

Rarely |

Sometimes |

Frequently |

Very frequently |

|

Scale |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6. Cik bieži saskaraties ar vārda diēta lietojumu latviešu valodā ar nozīmi ‘uzturs’? (How often do you encounter the word diet in Latvian with the meaning ‘general nutrition’?)

|

Answer type |

Very rarely |

Rarely |

Sometimes |

Frequently |

Very frequently |

|

Scale |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

7. Cik bieži saskaraties ar vārda fikcija lietojumu latviešu valodā ar nozīmi ‘kaut kas izdomāts’? (How often do you encounter the word fiction in Latvian with the meaning ‘something invented, made up’?)

|

Answer type |

Very rarely |

Rarely |

Sometimes |

Frequently |

Very frequently |

|

Scale |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

8. Cik bieži saskaraties ar vārda fikcija lietojumu latviešu valodā ar nozīmi ‘daiļliteratūra’? (How often do you encounter the word fiction in Latvian with the meaning ‘literature’?)

|

Answer type |

Very rarely |

Rarely |

Sometimes |

Frequently |

Very frequently |

|

Scale |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

9. Cik bieži saskaraties ar vārda afēra lietojumu latviešu valodā ar nozīmi ‘skandāls, krāpniecības gadījums’? (How often do you encounter the word afēra in Latvian with the meaning ‘scandal, case of fraud’?)

|

Answer type |

Very rarely |

Rarely |

Sometimes |

Frequently |

Very frequently |

|

Scale |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

10. Cik bieži saskaraties ar vārda afēra lietojumu latviešu valodā ar nozīmi ‘mīlas dēka, romāns’? (How often do you encounter the word afēra in Latvian with the meaning ‘love affair, romance’?)

|

Answer type |

Very rarely |

Rarely |

Sometimes |

Frequently |

Very frequently |

|

Scale |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

11. Cik bieži saskaraties ar vārda virāls lietojumu latviešu valodā ar nozīmi ‘kas attiecas uz vīrusiem/vīrusu izraisīts’? (How often do you encounter the word viral in Latvian with the meaning ‘relating to viruses/caused by viruses’?)

|

Answer type |

Very rarely |

Rarely |

Sometimes |

Frequently |

Very frequently |

|

Scale |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

12. Cik bieži saskaraties ar vārda virāls lietojumu latviešu valodā ar nozīmi ‘kaut kas ļoti populārs, īpaši interneta vidē’? (How often do you encounter the word viral in Latvian with the meaning ‘something very popular, especially on the internet’?)

|

Answer type |

Very rarely |

Rarely |

Sometimes |

Frequently |

Very frequently |

|

Scale |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

Third part of the questionnaire. Single choice questions.

13. Vai tulkošanas procesā esat novērojis/-usi, ka iepriekš minētie piemēri arvien biežāk tiek lietoti atbilstoši to nozīmei angļu valodā? (Have you noticed in your translation work that the above examples are increasingly being used in accordance with their meaning in English?)

• Jā, bieži (Yes, often)

• Nezinu, neesmu par to domājis/-usi (I don’t know, I haven’t thought about it)

• Reizēm (Sometimes)

• Reti (Rarely)

• Nē, neesmu (No, I haven’t)

• Cits (other)

14. Vai šādu vārdu tulkošana ir sagādājusi problēmas tulkošanas procesā? (Has translating such words caused problems in the translation process?)

• Jā, grūti saprast, ko runātājs ar to vārdu saprot (Yes, it is difficult to understand what the speaker means by that word)

• Jā, bet nojaušu vārda nozīmi pēc konteksta (Yes, but I understand the meaning of the word from the context)

• Atkarīgs no situācijas (Depends on the situation)

• Nē (No)

• Cits (Other)

15. Vai esat saskāries/-usies ar līdzīgiem piemēriem, tulkojot no citām valodām, izņemot angļu? Ja jā, lūdzu, norādiet to pie atbildes “Cits”. (Have you encountered such examples when translating from languages other than English? If so, please indicate this in the response ‘Other’.)

• Jā (Yes)

• Nē (No)

• Nezinu, neatceros (I don’t know, I don’t remember)

• Cits (Other)

Vieta komentāriem, ja tādi radušies. Vēlreiz pateicos! (A place to leave comments, if you have any. Thank you once again!) Nonmandatory question.