Vertimo studijos eISSN 2424-3590

2025, vol. 18, pp. 79–103 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/VertStud.2025.18.5

Gunta Ločmele

University of Latvia

gunta.locmele@lu.lv

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6094-2791

Abstract. Adverts are part of linguistic landscape both reflecting and influencing the processes in language. This article examines instances of code-switching in Latvian translated advertising. Code-switching in advertising appears to be topic-related: the largest number of cases seems to occur in the field of technologies due to its rapid development; however, other fields—particularly those of somewhat lesser economic significance, such as cosmetics—demonstrate it as well. English influence in advertising leads to hybridisation, orthographic changes, semantic changes, and awkward syntactic constructions, partly perpetuated by machine translation and other AI tools. Although AI technologies have improved over the period of the study, as demonstrated by several examples, human-led expertise is still required in the transcreation of advertising.

Keywords: transcreation, advertising, code-switching, linguistic landscape, machine translation, AI

Santrauka. Reklamos yra kalbinio kraštovaizdžio dalis, jos ne tik atspindi, bet ir veikia kalbos procesus. Šiame straipsnyje nagrinėjami kodų kaitos atvejai latviškai išverstoje reklamoje. Kodų kaita reklamoje dažniausiai priklauso nuo temos: daugeliu atvejų ji pastebima technologijų srityje dėl spartaus jų vystymosi, bet pasitaiko ir kitose, net ir tokiose mažesnės ekonominės svarbos srityse kaip kosmetika. Dėl anglų kalbos poveikio reklamoje atsiranda hibridizacija, ortografiniai pokyčiai, semantinės slinktys ir gremėzdiškos sintaksinės konstrukcijos, kurias iš dalies palaiko mašininis vertimas ir kiti DI įrankiai. Nors DI technologijos per tyrimo laikotarpį patobulėjo, kaip rodo keli pavyzdžiai, perkuriant reklamas konkrečios auditorijos poreikiams vis dar būtinas žmogaus išmanymas.

Pagrindiniai žodžiai: perkūrimas, reklama, kodų kaita, kalbinis kraštovaizdis, mašininis vertimas, dirbtinis intelektas.

___________

Copyright © 2025 Gunta Ločmele. Published by Vilnius University Press

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

The era of the digital revolution has left its mark on the Latvian language of advertising, which is shaped not only by transcultural influences—mainly from English translations—but also by modern technologies. The aim of the study is to examine the occurrence of code-switching in translated advertisements in the Latvian market, to assess the role that machine translation (MT) and artificial intelligence (AI) may play in their translation, and to analyse how these processes influence the Latvian language.

The material for this study consists of translated advertising texts from 2023 to 2025. These include advertisements published in print magazines, online brochures, webpages, banners, and posters. The selected examples represent a range of commercial fields and illustrate how English–Latvian code-switching appears in advertising communication in Latvia. For a broader illustration and comparison, some advertisements from earlier years were used. To assess the role of MT and AI in shaping these texts, the same advertisements were additionally translated using selected MT and AI systems. Comparing human-produced and technology-generated translations provides insight into the extent to which digital translation tools contribute to code-switching and how both types of translation may influence contemporary Latvian language use.

The advertisements for the analysis were selected based on two criteria. First, they were translations or contained translated elements. Second, they exhibited instances of potential code-switching on lexical or syntactic levels. To assess the role of MT and AI in shaping code-switching practices, each selected advertisement was additionally translated using two types of tools: a widely used neural MT system (Google Translate and/or DeepL (Classic)), and a contemporary generative AI model ChatGPT-4 (in 2024); ChatGPT5 (in 2025), or Gemini 1.5 Flash (prompt: Translate the advertisement from English into Latvian). The human-translated advertising texts and the MT/AI-generated versions were compared to identify similarities and differences in lexical choices, syntactic structures, and the presence or absence of code-switching. The study applied a qualitative linguistic analysis grounded in code-switching typologies, translation studies approaches to adaptation and transcreation, and the designer-of-meaning perspective, which views readers as active constructors of meaning. Each example was examined with regard to the type of code-switching employed, its possible communicative effect, and its potential impact on Latvian language use. To address the broader aim of understanding the influence of these processes, the analysis considered the semantic or stylistic shifts introduced through MT/AI output and cases where inappropriate code-switching may hinder meaning design by consumers.

Kelly-Holmes (2005: 2-3) argues that historical, political and economic relations between countries and regions determine many contemporary marketing messages. This coresponds to the previous research, for example, Haarmann’s (1989) observations on language contact: the prestigious status of English and other European words in Japanese media, particularly in advertising, and linking them to the attitude of people towards these cultures (Haarmann 1989: 4). Haarmann also notes that stereotypes are evoked by foreign words (Haarmann 1989: 29).

Kelly-Holmes (2005: 10-11) also argues that people may be more accustomed to using specific codes or languages when discussing certain topics, which might explain the use of English words in advertisements for some technical products. Along the same lines, Bhatia (1992:195) describes English as the language of technology and innovation. A decade later, Elisabeth Martin (2002: 382-383) applies Kachru’s labels (Kachru 1986: 136) to symbolise the global power of English, thereby expanding the way in which English is perceived, including advertising. Among these labels, the most relevant for the present research are modernisation, liberalism, universalism, technology, science, and mobility.

Advertising reacts and adapts to the way texts change in a particular culture (Kelly-Holmes 2005: 5), and thus can serve as an indication of the processes of Latvian language development.

Although often perceived as a neutral and common issue, code-switching—as a multilingual phenomenon—can also reveal a lack of corpus planning in a particular target language (Dorian 1992, as cited in Kelly-Holmes 2005: 12); that could be the case of some domains of Latvian that are not viewed as a priority in language planning.

Grin (1994) models language use in advertising and consumer relations. Haarmann (1989), examining English in German adverts, concludes that languages in advertising are used symbolically. Cheshire and Moser (1994) reach a similar conclusion regarding the use of English in adverts in French-speaking Switzerland. Kelly-Holmes (2005: 22) describes this dimension of advertising as a ‘linguistic fetish.’

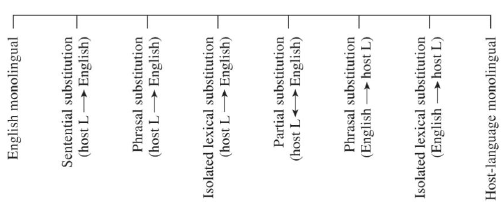

Martin (2002) analyses English elements in French magazine adverts, providing a cline that describes various patterns of code-mixing (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A cline of code-mixing in advertising (Martin 2002: 387)

The starting point of this cline is non-translated adverts in English placed in the French media. Another pattern relevant for the present study, which Martin calls ‘substitution,’ includes sentential substitution, phrasal substitution, and isolated lexical substitution (Martin 2002: 385). Sentential substitution (host L -> English) includes English sentences in French ads, while phrasal substitution (English -> hostL) refers to literally translated English phrases into the ‘host’ or target language. Such substitution does not necessarily convey the meaning of the source phrase (p. 385). These phrases and words are translated into the host language for special effect (Martin 2002: 398) or in order to identify with a group—either the addressee or the one referred to (Kelly-Holmes 2005: 13). These patterns are relevant for the present analysis, as some of these substitutions are found in the analysed material. Following Kelly-Holmes (2005), we use code-switching in advertising as a broader concept that includes code-mixing. Bhatia writes: “If language mixing is permitted in advertising, it is likely to exploit those untapped possible limits of either the mixed-language grammar or the absorbing-language grammar, which introduces innovative and creative effects into advertisements” (Bhatia 1992: 196). It seems that some of the grammatical features introduced by translation into Latvian do not fall into the category of creative effects indicated by Bhatia. Noting that adverts from around the world demonstrate a variety of grammatical and phonological experimentation, Martin (2002: 385) offers different perspectives for their analysis—phonological innovations, hybridization, experimentation with orthography, lexis, idioms, and translation—some of which will be discussed in the present paper.

The number of multilingual adverts is increasing. Already at the turn of the millennium, Piller wrote about 60-70% of multilingual adverts in German advertising (Piller 2001: 153), specifically mentioning English slogans at the end of the adverts that vested English “with the meaning of authority, authenticity, and truth” (Piller 2001: 160).

H. William Amos (2020) considers cases where a variety of one language is influenced by knowledge of another language, which increasingly seems to be the case in Latvian advertising. Amos refers to ‘bilingual winks,’ a term introduced by Mettewie, Lamarre and Luk Van Mensel (2012, cited in Amos 2020: 67–68) and used by other researchers (e.g., Lamarre 2014), which denotes a covert use of English within apparently French signs (Amos 2020: 67–68) and which may also appear in Latvian advertising. Amos concludes that advertising text producers in the linguistic landscape expand the usage of French by blending features of English and French in inventive ways. Therefore, advertisements constitute a useful data source for analysing multilingualism as “the result of a creative process that transcends formal boundaries.” (Amos 2020: 70) A similar analysis is important for Latvian as well.

A designer-of-meaning approach, developed in educational contexts (e.g., Adami, Diamantopoulou and Lim 2022; Kress 2010; Kress and Selander 2012; Selander 2008; Selander 2021) and stipulating that everyone engaged in the communication process of learning is a designer of meaning (Adami, Diamantopoulou and Lim 2022: 3; Kress and Selander 2012), is used in the present paper. Gunther R. Kress maintains that “Meaning is made in communication, whatever its form.” (Kress 2010: 32). There is a message that addressees frame for themselves as a prompt leading to further communicative action in a continuous semiotic process of attention → framing → interpretation (Kress 2010: 32). In the communicative discourse of advertising, the designer-of-meaning approach is particularly relevant, as modern consumers want to create their own stories and dreams about advertised products (Amatulli et al. 2018; Ločmele 2024b). However, these stories need to be professionally channelled leading to an expected framing, prompts and interpretation. Some of the cases of lexical, syntactic, and other types of code-switching discussed below, within the particular socio-cultural environment of Latvia, may create obstacles to the expected process of meaning design by consumers.

Various methods – translation, adaptation or localization – are used to translate adverts into Latvian. These methods are closely related; however, there are small differences. Translation is true to the original yet idiomatic. Adaptation takes into consideration the cultural aspects of the target market, adjusting the advertisement accordingly. Localisation is mainly focused on the advertised product and adapting it to the target market (medium.com). Adaptation by substitution, omission, as well as the inclusion of literally translated fragments in adapted advertisements in Latvian, are discussed by Ločmele (2021). However, it seems that transcreation is applied increasingly often. Transcreation, according to Mar Díaz-Millón and María Dolores Olvera-Lobo, is a translation-related activity that “combines processes of linguistic translation, cultural adaptation and (re-)creation or creative re-interpretation of certain parts of a text” (Díaz-Millón and Olvera-Lobo 2023: 347). Code-switching on various levels of language in the transcreation of advertisements is described in the following chapters, starting with the lexical level.

Translation leaves subtle marks of foreignness on the target text. These marks, originating from both human translators—who sometimes engage in code-switching, thereby introducing new meanings to existing words—and machine translation, highlight the lingering influence of English. In the advertising situation, some lexical code-switching instances lead to an unintended meaning design.

Terminology is an important area of a translator’s work that requires proper research, which is time-consuming. Not all of the solutions offered in the analysed material are successful. The modern era features the term “advanced threats” in advertising, particularly in relation to the geopolitical situation and cybersecurity. For example, the phrase “aizsardzība pret progresīviem draudiem” [literally, protection against progressive threats] (Klubs 2023 No. 11: 2) is used as a phrasal equivalent of the English term “Advanced Threat Defense” in the source text (ESET Protect Elite 2024).

In the Latvian National Digital Library’s newspaper collection Periodika (Periodika 2024), the adjective progresīvs [progressive] appears at the end of the 19th century, and its use increases rapidly in the second half of the 20th century. At the end of the 19th century, the term, as it entered journalism, primarily referred to something that gradually increases or intensifies (Baldunčiks and Pokrotniece 1999). The meaning “new, modern, contemporary” was rare, as in weenota progreẜiwa walẜts [a united progressive state] (Baltijas Vēstnesis 1903). In contrast, during the Soviet era, progresīvs was overwhelmingly used in the sense of promoting progress (Baldunčiks and Pokrotniece 1999). For instance, in the magazine Karogs from 1940 to 1995, the word progresīvs appears 6,009 times, of which only four instances are compounds related to gradual increase or intensification. The remaining uses describe communist ideals, serving as a form of propaganda.

These historical meanings contribute to semantic tension in the modern term progresīvie draudi. In advertising, the word must simultaneously convey the idea of growing threats and align with a generation familiar with its historical sense of promoting progress (Ločmele 2024a: 55–56). AI translation suggestions for the term Advanced Threat Defence include uzlabota draudu aizsardzība [improved protection of threats], paplašināta draudu aizsardzība [expanded protection of threats] (both suggested in May 2024 and July 2025), and progresīva draudu aizsardzība [progressive protection of threats] if a more technical or modern tone is desired (Chat GPT July 2025). Gemini (July 2025) suggests uzlabota aizsardzība pret apdraudējumiem [improved protection against threats, using a synonym], which clearly indicates protection against threats rather than protection of the threat itself, representing an improved solution over time. This contrasts with the very general kiberdraudu atklāšanas un reaģēšanas risinājums [cyber threat detection and response solution] offered by Gemini in May 2024.

Machine translation tools offer additional variants. DeepL provides both the imprecise uzlabota draudu aizsardzība and the clearer uzlabota aizsardzība pret draudiem (May 2024 and July 2025), while Google Translate offers the clearer form uzlabota aizsardzība pret draudiem (May 2024 and July 2025). Although these translations are acceptable in advertising contexts aimed at mixed audiences—including both general readers of the men’s magazine Klubs and specialists—the precise meaning of the compressed term advanced threat, or in its full form advanced persistent threat (“a cyberattack in which the threat actors gain unauthorized access to a network or system with the intention that they remain undetected for a prolonged period of time” (techopedia.com)), is not fully conveyed by either human translators or AI. All the solutions discussed appear to be phrasal substitutions, as noted by Martin (2002: 385), which do not completely transfer the meaning of the source phrase. Therefore, it may be useful to consider employing the participle progresējošie, which appears to carry less semantic tension than progresīvie and brings into the scope of the advert’s intended meaning design those audience members who still strongly perceive the word’s positive connotation—an effect that is unwanted in this advertisement.

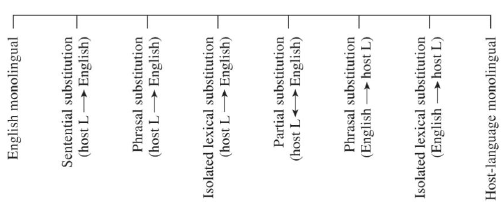

AI does not yet seem capable of providing transcreation, or information change—a pragmatic strategy described by Andrew Chesterman (2016: 106). In the translated advert for the Ford truck, the term “payload” (Latvian: kravensība) is replaced with vilktspēja [towing capacity], and a play on words based on the term appears in the translation of the subheading: “Šis pikaps tiešām pavilks” [This pickup will really tow].1. The transcreation of the source text “Hauls the most in its class”2 is successful. Although the literal meaning of pavilkt is “to tow,” the verb in Latvian slang also means “cope with something” or “be capable” (Bušs and Ernstsone 2006). DeepL provided a word-for-word translation: “Pārvadā visvairāk savā klasē” (DeepL July 2025). ChatGPT, on the other hand, offers two alternatives for the translation: “Savā klasē velk visvairāk” and a more idiomatic “Savā klasē vislielākā kravnesība” [the greatest load capacity in its class] (ChatGPT July 2025). However, they are less creative than the human version.

However, due to a human error by the translator, a humorous spelling mistake appears: vilktspēja is misspelled as vilkspēja, literally “wolfpower”. Vilkspēja [wolfpower] would have been a good metaphoric solution for a wordplay in the text; however, it is not appropriate in a place where the precise term vilktspēja is required together with the figure “3,5 t,” which provides the exact technical specification of the truck. The obstacle in meaning design appears to result from a human error in the transcreated, or re-designed (Selander 2021: 10–11), Latvian text. The target text seems not to have been edited, as it contains another error—a wrongly used capital letter.

Lexical substitution, in Martin’s (2002) terms, in this example is a literal translation of the verb “take off” in “helps take some of the weight off.” It is translated as nomest — “palīdz nomest daļu svara.” The code-switching is indicated by inverted commas to show that it is not to be understood literally, as throwing off part of the weight, but idiomatically.

The term pikaps, used in the translation, cannot be treated as an instance of code-switching from today’s perspective; however, it has undergone a shift in meaning since the 1960s-1980s when it first entered Latvian—likely from Russian in a transcribed form of the English word “pickup”—it referred to Soviet cars with a rear door. For example: “Žigulis pikaps: Janīnas pikaps, “žigulis”, kurā viņa brauc” [Janina’s pickup, “žigulis” that she drives] (Bremze 1977:1). A concordance search of the Soviet newspaper Cīņa yields 65 occurrences of pikaps in this sense. After Latvia regained independence and its economy revived, the meaning of pikaps shifted to denote pickup trucks, influenced by English as Western vehicle models entered the market. The term was Latvianised by adding the masculine case ending -s. However, the re-design in the advert’s terminology, as well as the picture featuring the advertised truck, provide the intended design of meaning even for consumers who might still remember the Soviet cars they used to own.

AI can provide translations and avoid spelling mistakes; however, it cannot capture the intricate web of meanings and connotations associated with the term. ChatGPT’s explanation of the borrowing of pikaps (August 2025) does not trace the term further back than the 1990s, by which time it was already used to denote imported pickup trucks.

The traces of English influence are quite pronounced in the realm of false friends. An instance in which the intended meaning design can go astray is the translation of an advertisement for the products of the company Vitabalans. The company uses the tagline “Finnish pharmaceutical expertise since 1980”3 on its English webpage. The Latvian version of its homepage reads “Somijas farmācijas ekspertīze kopš 1980 gada.”4 The word expertise has been translated into Latvian as ekspertīze, however, in Latvian ekspertīze means expert examination undertaken in order to provide an expert opinion (tezaurs.lv). Thus, the lexical substitution here is not successful. The advert has been translated into 15 languages, and 12 of them use different renditions of the word. For example: Finnish – osaamista (know-how), German – Kompetenz (competence), Swedish – kunskap (knowledge), Lithuanian – patirtis (experience), Czech – kvalita (quality). In this case actually machine translation provided a better solution: both DeepL and Google Translate rendered it as pieredze (experience) and even corrected a punctuation mistake of the published advert by adding a full stop after the year, which is a norm in Latvian: “Somijas farmācijas pieredze kopš 1980. gada.” (DeepL; Google, May 2024 and August 2025).

English phrases enter Latvian through translations, at first sounding strange and being perceived as false friends, but gradually they are accepted. As a result, some Latvian words, under the influence of English, change their meaning. For example, in Latvian the noun rutīna (routine) has several meanings - both a skill acquired at work and a patterned, conservative way of doing things (with a slightly negative connotation) (tezaurs.lv); and, in informatics, a part of software or a sequence of instructions that perform a specific task and have frequent application (tezaurs.lv). However, in translations of cosmetic product advertisements from English, another meaning is used more and more frequently: simple everyday activities carried out regularly (dictionary.com 2023). In the advertisement described in Ločmele (2024b: 72), the phrase “the morning routine” in the L’Oreal Paris Revitalift Clinical serum campaign is rendered through phrasal substitution as “Tava rīta rutīna ar C vitamīnu” (Lilita 06.2023, inside cover). When this advert was translated by MT in August 2024, DeepL produced an even more radical version – the plural form rutīnas – although in Latvian the noun is only used in the singular (rutīna), thereby taking the next step in changing Latvian lexis and grammar. By 2025, the plural ending had been removed in the translation, but the same word rutīna was used (DeepL August 2025). (Some further examples with rutīna in adverts are discussed in Ločmele (2021: 51)). It seems that MT continues to use a meaning of the word that is not yet fixed in dictionaries but is becoming part of the borrowed vocabulary in the beauty care domain. Chat GPT also provides the same rīta rutīna (Chat GPT August 2025) as the most common equivalent; however, it offers two alternative versions, which appear to be less useful from a designer-of-meaning perspective: ikdienas rīta ieradumi [daily morning habits], which might be less attractive for advertising purposes, and the more poetic rīta rituāls [morning ritual], which might be a good solution in an advertising context but is too pompous for the given sentence.

Even when attempting transcreation, translators often get caught in word traps. For example, when trying to preserve the same meaning, the polysemous English word “charge” is rendered by the Latvian word uzlāde, which does not have the same degree of polysemy. The word “charge” appears several times in the source text with multiple meanings, for example, in the headlines “Electrify your future. Take charge of today,” and “Always in charge. Wherever you are”5. In the Latvian transcreation, uzlādēts is used once in a headline where a different meaning of the word “charge” is applied rather artificially: “Kia e-Niro – uzlādēts ar lielisku aprīkojumu” [Kia e-Niro – charged with excellent equipment]6, corresponding to the pattern of phrasal substitution in Martin’s cline of code-mixing (Martin 2002: 385). Even though the example is a magazine ad, one possible reason is that “charging” is included in the Search Engine Optimisation (SEO) keywords for electric cars, and the Latvian version therefore needed the word uzlāde, since this is the accepted Latvian term for charging a car battery (termini.gov.lv). Another expression from one of the same headlines, “Electrify your future”, has also been transferred into Latvian in a partly modified way: “Elektrizē savu dzīvi ar jauno Kia e-Niro!” [Electrify your life with the new Kia e-Niro]7, thereby, through phrasal substitution, creating a new and unusual verbal metaphor in Latvian. ChatGPT offers several solutions for the translation of the headline in September 2025: “Elektrificē savu nākotni” – a word-for-word translation that might suggest electricity network installation; “Iedarbini savu nākotni ar elektrību” [power up your future with electricity]; a metaphoric yet somewhat far-fetched “Apgaismo savu nākotni” [illuminate your future]; and “Uzlādi savu nākotni” [charge your future] – a good solution with the verb uzlādēt, which has the same root as uzlāde above, though it contains a grammatical mistake in the verb ending. DeepL offers two alternatives: “Elektrificējiet savu nākotni” – similar to the first option by ChatGPT, yet using a more formal second-person plural form of the verb, and “Elektrizē savu nākotni” – a closer translation to the published one (DeepL September 2025).

The picture that should trigger the customer’s dreams and designer-of-meaning approach — which, according to Amatulli et al. (2018), is the main way of communicating with the modern audience who want to assign their own meanings to advertising messages and fulfil their desire to dream— is not in sync with the headline. Due to its rather artificial and incorrect phrasing, the headline actually disrupts readers’ dreams (Figure 2). By contrast, the pictures without text in the source internet brochures fulfil the task of provoking dreams more effectively (Figure 3). The word “charge”, with its multiple senses, is used successfully in the source text.

Figure 2. [Kia e-Niro – charged with excellent equipment]. Klubs 2023, No. 11: 5.

Figure 3. Kia Niro brochure8

The pressure of English is observed in advertising language across all languages (Amatulli et al. 2018: 72). In Latvian, English words occasionally acquire hybrid forms, borrowing English features that are combined with Latvian morphological ones, particularly case endings. For example, the English name “wrap-burger” is used as a brand name for a product by the Latvian company Astarte Nafta in their advert “Nogaršo! Kebabs un Wrapburgers”9. As Geoffrey Leech noted as early as 1966—when there was no real advertising in Latvia under the Soviets—breaking orthographic rules was a common practice in brand names (Leech 1966: 177). However, in the case of Wrapburgers the word has travelled from advertising into the Latvian language as a common noun, written with the letter w, which is not part of the Latvian alphabet (for example, veģetārais wrapburgers10). Even if it is only a passing phenomenon, it influences the ecology of the language and recalls the time when w was among the letters used in Latvian spelling for the sound v, following the German alphabet up to the beginning of the 20th century.

As the word is not included in Latvian dictionaries—for example, it is absent from the open explanatory online dictionary Tēzaurs—Latvian Tilde MT offers the nonsensical ietinamais burgers in May 2024, and the even more nonsensical ietīšanas burgers [a burger of wrapping] in September 2025. Google Translate produces wrapburgers, while DeepL suggests the even less grammatically correct wrap burgeris in May 2024 and burgeru iesaiņojums [wrap for burgers] in September 2025. The reason for the use of the word in Latvian might be SEO, as the Google search engine lists wrapburgers among its search prompts. However, AI offers a more Latvianised transcription, vrapburgers, in September 2025 (ChatGPT September 2025).

The fields that are not priority sectors for the economy face rapid ad hoc terminology development under strong negative pressure from the English language, and advertising plays a role in this process. Some of these ad hoc terms begin to form clusters, perpetuating foreign elements in Latvian spelling. Thus, alongside wrapburgers, the English noun with a Latvian ending, wraps, is used in Latvian to denote a type of sandwich11, however, Latvian transcription vraps is used as well. In 2015, the Latvian Language Expert Commission decided that the Latvian word tītenis should be used as the name for the fast-food staple “wrap” (LVEK 2015). The name was considered “ponderously Latvian” (DELFI 2015) and is not used in advertising, apparently because it may lead the audience’s meaning design toward an unwanted association with cabbage rolls, which have long been known by this name in Latvia.

If MT may not solve the problem of polysemy and ad hoc terminology, in the translation of the headline of the Ford-150 advert “Keeps on towing. Day in, day out and day off”12 the MT may cope with the task, as Latvian allows for a word-for-word rendering “Turpina vilkt. Dienu no dienas un brīvdienās”13. The repetition in the source text is preserved by repeating the same part of a compound in the Latvian target text. DeepL provides exactly the same translation, but also offers an alternative version, which contains fewer repetitions: “Turpina vilkt. Katru dienu un brīvdienās” […Every day, including weekends] (DeepL September 2025). ChatGPT gives an overly exhaustive translation “Turpina vilkt. Katru dienu, darba dienās un brīvdienās.” […Every day, on weekdays and weekends], and another, similar to DeepL’s: “…Katru dienu un brīvdienās” (ChatGPT September 2025).

However, a human touch appears in the transcreation, where the pragmatic strategy of information change is applied: the “Tow rating of 14,000 lb.” in the source is rendered as “uzticams spēks” [reliable force], which generalises the specific term and feature in the target text.

Considering the picture that might be dream provoking (Figure 4), it, however, would have fulfilled its task of triggering the expected design of meaning by the customer much better if the trailer was of the type typically seen in Latvia. The customer engagement is decreased by the lack of adaptation of the visual. Long forgotten is the time when, in the interwar Latvia, Ford cars were produced in this country (Wirtschaftsnachrichten 1939), the truck F-150 is quite exotic in today’s Latvia and makes its advance into the market rather slowly.

Figure 4. https://f150.autoblitz.lv/ (accessed 06.08.2025).

In another example of a truck advert, a possibly human translation of the headline “Monstrous power that begs to be unleashed”14, rendered word-for-word with awkward syntax as “Monstrozā jauda, kas lūdz tikt atbrīvotai”15 uses lexical substitution from English, resulting in a rather rarely used adjective monstrozs. The Balanced Corpus of Modern Latvian (LVK2022) shows only 26 usages of the word, one of which also describes a truck: “Šis monstrozais “Trophy Truck” aprīkots ar “Chevrolet” V8 dzinēju [..]”16 [The monstrous “Trophy Tuck” is equipped with “Chevrolet” V8 engine…]. In this advert, however, the truck bears a company logo, “Monster Energy” (Figure 5), so the use of the word monstrozs with the same root serves its intended meaning design purpose.

The syntactically and morphologically awkward Latvian phrase “kas lūdz tikt atbrīvotai” is rendered much more successfully by machine translation. DeepL (May 2024) converts the English infinitive construction “that begs to be unleashed” into the idiomatic subordinate clause “kas prasa, lai to atraisītu”, preserving both syntax and meaning. ChatGPT (September 2025) provides slightly improved morphology, yet the usage of the adjective briesmīgs [terrible] seems too colloquial: “Briesmīga jauda, kas alkst tikt atbrīvota.”

Automotive adverts seem to show a strong influence of English, including technical abbreviations, English-origin words, and even syntax. This observation aligns with Kelly-Holmes’ argument regarding topic-relatedness in code-switching (Kelly-Holmes 2005: 10–11).

Figure 5. https://www.delfi.lv/auto/42826658/zinas/43193656/video-850-zs-pikaps-plosas-pa-tuksnesi (accessed 07.08.2025).

Lexis can have a creative power to carry a consumer’s dream across borders; however, to do so, the message needs to be professionally transcreated. The foreign words may have a symbolic nature (Kelly-Holmes 2005); however, their implications in the target culture need to be carefully assessed.

There are word-for-word translations in Latvian that seem to be intentional; however, the resulting impression is of a bad style. For example, in April 2024, the Toyota Relax Guarantee advert “Keep your car under warranty for up to 10 years”17 had a Latvian version containing a word-for-word translated phrase describing the warranty period: “uz līdz 10 gadiem”18 [for up to 10 years], where the two prepositions uz and līdz used together were redundant. However, either due to lack of technical knowledge and fear of altering the meaning, or due to concern over legal consequences in case of customer misinterpretation, this awkward construction followed the English pattern. A better textual solution that preserved the same legal meaning was later adopted. In August 2025, the same guarantee was offered with a more natural Latvian phrase: “līdz tavs Toyota ir 10 gadus vecs”19 [until your Toyota is 10 years old]. DeepL offers a slightly different but clear and grammatically correct version: “Saglabājiet savam automobilim garantiju līdz pat 10 gadiem” (DeepL September 2025). The translation of the second part of the sentence by ChatGPT, “līdz pat 10 gadiem” (ChatGPT September 2025), sounds natural, although the first part is translated word-for-word, “Uzturiet savu automašīnu garantijā” (ChatGPT September 2025), which makes little sense in Latvian.

In some cases, word-for-word translations from English seem to be used for creating humour. For example, the used car dealer Longo advertised the Hyundai Tucson on their Facebook page with a phrase seemingly spoken by the car: “Uzturēšu romanci karstu ar saviem apsildāmajiem sēdekļiem”20 [I’ll keep the romance hot with my heated seats]. Romance in Latvian refers either to a lyrical song or poem, usually about love (tēzaurs.lv). The phrasal substitution here is used to appeal to young people who know English and seem to enjoy this kind of code-switching, which could be described as a “bilingual wink” (Amos 2020). It engages customers in the meaning design process.

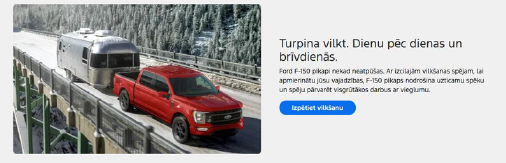

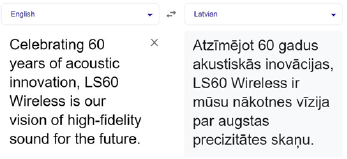

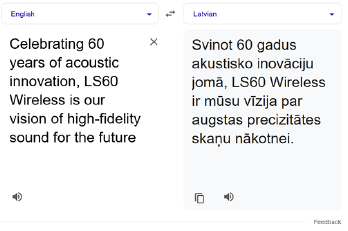

Syntax plays an important role in transcreation. Unfortunately, there are cases where the negative impact of English is observed, and in some instances this seems to result from non-edited machine translation. For e xample, for reasons that are not clear, a magazine advertisement for speakers was machine-translated word-for-word, as evidenced by its nonsensical word order influenced by the English “of”-phrase, which is not used in Latvian: “Atzīmējot 60 gadus akustiskās inovācijas […]”21. The most common tool, Google Translate (Figure 6), appears to have been used to translate the English source text “Celebrating 60 years of acoustic innovation, LS60 Wireless is our vision of high-fidelity sound for the future”22 in 2023. However, the client Audiotehnika’s, website had a much more successful text in Latvian, “Atzīmējot akustiskās inovācijas 60 gadus [..]23” at the time the magazine advertisement was circulated.

Figure 6. Translation by Google Translate, April 2024.

In the summer of 2025, Google Translate offers a considerably improved translation of the same source phrase (Figure 7), adding the word joma [a field], resulting literally in: “celebrating 60 years in the acoustic innovation field.”

Figure 7. Translation by Google Translate, August 2025.

Even with improvements in MT translation, human post-editing of texts remains important. Moreover, ChatGPT, in September 2025, offers the same faulty word-for-word translation, “Atzīmējot 60 gadus akustisko inovāciju […]”, confirming that the English influence on Latvian syntax may still persist. The awkward or cumbersome syntactic constructions may not stimulate the designer-of-meaning approach, but rather slow down the decoding of meaning by the customers.

There are cases in which translations of the same advert on magazine covers are changed, seemingly for reasons related to translation quality and its impact on the customers’ meaning design process. For example, a source text for the MBL Reference Line audio system has two different target text versions in the women’s magazine Santa (03.2023: inside back cover) and in two issues of the men’s magazine Klubs. The version in Santa and in the March 2023 issue of Klubs (03.2023: inside front cover) seems machine-translated, or else is a human translation containing a number of flaws. Another version, in the next month’s issue of Klubs (04.2023: back cover), appears to be human-edited or human-translated. It is possible that the advertisers assumed men are more likely customers for these expensive luxury systems (prices range from 20–40 thousand for a Reference Line CD, to 300,000 and more for the whole system) and therefore need an improved version of the advert compared to the one published in Santa and the earlier Klubs issue; consequently, it was changed (see Table 1).

Table 1. Changes to the word-for-word translations in the advert for MBL Reference Line

|

Sours Text24 |

“Santa” and “Klubs” 03.2023 (word-for-word translations) |

“Klubs” 04.2023 |

|

“High quality materials with an uncompromising level of refinement” |

[...] bezkompromisu līmeņa apdare |

[…] bezkompromisa apdares līmenis (the translation is better adjusted to Latvian grammar) |

|

“With its magical sound MBL conquers every listener” |

Ar savu maģisko skanējumu MBL iekaros ikvienu klausītāju! [[..] will conquer every listener] |

Ar savu maģisko skanējumu MBL aizrauj pilnīgi ikvienu! [[..]fascinates absolutely everyone] |

Besides the numerous stylistic changes also made in the second version of the translated advert, the lexical change stands out. The first translation had the phrase in Latvian kulta ražotājs [cult producer], with the noun kults, which in Latvian, besides religious worship, denotes adoration or exaggerated treatment as something very important (tezaurs.lv). The second version of the translation used the adjective ikonisks, related to an icon and denoting a quality characteristic of an icon (tezaurs.lv). This somewhat more modern word (218 hits in a concordance search, LVK2022) seems to be gaining popularity under the influence of the English word “iconic.” The source text had a reference to the “canonical status” of the audio system, which both DeepL and ChatGPT render as kanoniskais statuss in September 2025. The adjective kanonisks in Latvian denotes something that is considered the only correct example.

Notably, the hybrid term High-End klase is retained unchanged in the new translation version, which, similarly to the case of the automotive industry described above, relates to Helen Kelly-Holmes’ argument (2005: 10–11) on the topic-relatedness of code-switching, especially for technical products; in Latvian, this also applies to audio technologies. MT provides augstākā klase [highest class] (DeepL August 2025) or the repetitive Augstākās klases klase [class of Highest Class] (Google Translate August 2025) as translations for “High-End class,” which does not seem to satisfy experts in the audio system market. However, in September 2025, ChatGPT offers High-End klase among other versions.

Although English is the main source language in advertising, with the most pronounced influence, translations are also made from other languages. Elmenhorster, an originally German brand, has been producing fruit juices and beverages in Lithuania since 1997. The Lithuanian advert for the brand, “Laikas sultims. Laikas pokalbiams.”25, is translated into Latvian as “Laiks sulai. Laiks sarunām.”26 [Time for juice. Time for talk]. The word-for-word translation, which appears to be made from Lithuanian, works well, partly because both languages belong to the same Baltic branch of the Indo-European language family.

Probably beverage companies share the same method of research and have come up with similar ideas about what would be most appealing to their market, thereby triggering the expected designer-of-meaning approach. “Laiks sarunām.” [Time for talks] is used as a brand name by the local coffee makers Dadzis27, and wine producers28 as well. “Laiks draugiem. Laiks Bonaparte.” [Time for friends, time for Bonaparte] (Klubs 2012, No. 11) was used by a local brandy producer.

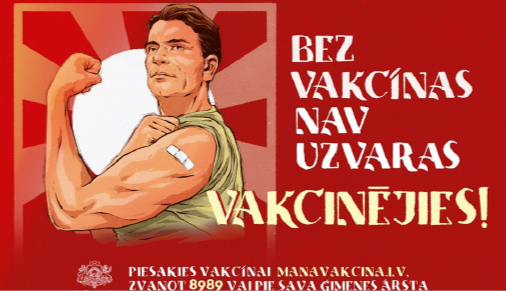

Researchers underscore a participatory perspective in sign creation, the creation of meaning, and the coding and decoding of ideas (Adami, Diamantopoulou, Lim 2022; Berra 2020: 33; Kress 2010). The design of meaning and societal participation may influence the quality of adverts. The question remains whether AI will remain merely an assistant to human-created advertising, or whether human creations will be used only in strategically important campaigns, such as state image, security, or social campaigns (e.g., vaccination). Society’s involvement as a designer of meaning is quite pronounced. For example, Latvian society got involved in the design of meaning in the Latvian Ministry of Health’s Covid-19 campaign under the slogan “Bez vakcīnas nav uzvaras” [No victory without a vaccine] (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Poster of the advertising campaign “Bez vakcīnas nav uzvaras” (Ambote 2021).

It was widely discussed in society and by the media in 2021. The similarity with the campaign in the United States was one of the reasons for criticism. The posters were made in the style of national romanticism, as explained (Ambote 2021). They alluded to the slogan by Latvian designer Ansis Cīrulis for the Latvian Riflemen during the Freedom Fights against Germans in World War I (1917), “Bez cīņas nav uzvaras” [No victory without a fight], but also to the US poster by J. Howard Miller during World War II, “We Can Do it”29 The development of the creative idea for the vaccination campaign cost about €70,000. No plagiarism was found by the Latvian Advertising Association.

Other posters of the same campaign – “Bez vakcīnas nav teātra” [No theatre without a vaccine], “Bez vakcīnas nav ballīšu” [No parties without a vaccine], “Bez vakcīnas nav sacensību” [No sports competition without a vaccine], “Bez vakcīnas nav mācību” [No studies without a vaccine] seemed too far removed from the historical slogan and, in a way, reduced its historical meaning to banality. The historical slogan has actually revived in popularity not because of its use in these posters, but due to the current geopolitical situation, and has been printed on T-shirts by the Latvian company Miesai (miesai.com).

This example illustrates the intricate relationships between words, texts, and images in today’s world, where not only words but also images and ideas are borrowed, linked to elements in the target culture, codes are mixed and transformed in a transcultural environment shaped by the socio-political context.

All of the discussed cases illustrate the linguistic landscape of Latvia. The linguistic landscape is understood by Berra (2020: 26) both as a set of linguistic signs and as a way of looking at the linguistic situation in localities. Ivkovic and Lotherington (2009) extend this study to virtual space, and Hiippala, Väisänen and Pienimäki (2024) demonstrate a multimodal approach to the study of physical and virtual linguistic landscapes. The linguistic landscape is expanding—shifting to the internet, where it is increasingly influenced by texts produced by AI. According to Kress (2010), the media landscape also plays an important role in modern communication. Looking at various factors included in the media landscape (Kress 2010: 21–22), advertising is influenced by processes of glocalisation and multimodality. It appears that in advertising, the linguistic landscape and the media landscape interact. Furthermore, advertising is part of the virtual linguistic landscape. The linguistic landscape of Latvia, as demonstrated by these examples, includes not only sets of linguistic signs in localities but also the virtual space, with multimodality in both, which seems to be shaped by the use of technologies. Multimodal advertising texts and their translations travel between virtual and physical spaces in various ways and are increasingly influenced by AI.

According to the ecolinguistics approach advocated by Leo van Lier (2004) and, in the Latvian context, discussed by Solvita Berra (2020), not only oral, but also written communication may feature distinctive word combinations and unconventional syntactic constructions. They may also include textual structuring strategies that do not always align with the norms of standard literary language or represent its accepted variation (Berra 2020: 24–25). These features are observed in Latvian advertising and, in many instances, are the result of code-switching in translations, including machine-generated ones. In many instances, they channel the designer-of-meaning approach in the intended way; however, in some cases, they do not, as they contain obvious mistakes. The question arises whether they become an accepted part of the linguistic landscape, or whether society should continue to question and resist them. Lazdiņa and Pošeiko (2015: 96) argue that

it is possible to discuss public texts with obvious and significant linguistic errors, highlighting the issue of the responsibility of linguistic landscape actors (authors, technical producers, readers) for the preparation, placement, and replacement of texts in public space, and the perceptual difficulties associated with such linguistic signs (translation mine).

The positive effects of public involvement in correcting errors that hamper the proper design of meaning are illustrated by the example of the scores of the Latvian Anthem. In 2024, a multimodal poster in the Riga municipality campaign marking the anniversary of the restitution of Latvia’s independence featured the text and musical scores of the Latvian Anthem. The text was displayed correctly, but the musical scores contained errors. A Latvian musician corrected them in red on the posters in the street, noting that this was a significant piece that could not be displayed incorrectly. The public discussed the case on the social platform X (@Kolliss, 26.04.2025), prompting the municipality to replace the posters. As a result, the designer had to pay a fee for the mistake. The errors might have been avoided if AI had been used in executing the human idea—during production and copying processes.

Translators, although not mentioned by Lazdiņa and Pošeiko, should be viewed as linguistic landscape actors. In situations where a considerable number of advertising texts seem to be produced for SEO, AI may replace MT in text production. The fact that AI is used to optimise content for SEO, ensuring that it aligns with search engine algorithms and ranks higher in search results, is acknowledged by advertising agencies (see Red Pencil 2023). However, the human role in the process of creating engaging, culturally and linguistically nuanced texts should not be underestimated.

The pressure of English seems to be present on all levels of the Latvian advertising language: lexis, with brand names that have the potential to occasionally develop into common nouns; syntax; and even seemingly intentional word-for-word translation and content optimisation for SEO, which might influence textual choices and code-switching. The pressure of English may lead to the standardization of communication, the ‘homogenization’ of consumers’ interpretation, and the dilution of customer engagement (Amatulli et al. 2018: 72) in the meaning design process intended by the text. AI can translate from any language with varying degrees of success; however, most borrowings still come from English, even though ideas circulate among neighbouring countries, and meanings are designed on a regional basis and might demonstrate some homogenisation of ideas. Identical advertising concepts in both Latvian and Lithuanian, and even globally, were observed.

The question, “Can a machine help?” can be answered positively, particularly in areas where humans tend to make mistakes. If advertisers, copywriters, and translators adopt a designer-of-meaning approach in both creation and research within the advertising space, this could result in more creative advertising without cultural mistakes.

As Helen Kelly-Holmes argues, “it [advertising] is absolutely flexible and adaptable. As changes occur in the structures and texts of the particular culture or society, then advertisements too will respond to this” (Kelly-Holmes 2005: 5). The AI era has begun to impact advertising language in Latvia. MT and AI are constantly improving, as demonstrated by correct solutions replacing erroneous ones over just a little more than a year. However, some problematic solutions persist because they may have seeped into language use due to a lack of better terminology (e.g., wrapburgers), or reflect ongoing changes in the language (e.g., changes in the meaning of rutīna). Advertising both reflects and drives change by perpetuating its features (Ločmele and Komarova 2024). In the case of the Latvian language, AI and MT do not appear to cause change themselves; rather, they reflect changes driven by the influence of English and may contribute to perpetuating them.

Sources

Bremze, Imants. 1977. Izsauc «LATGALE-5». Cīņa. No. 206. 1.

DELFI 2015 - No vrapa par tīteni, no selfija par pašfoto – spilgti Valsts valodas centra verdikti [From vraps to tītenis, from selfijs to pašfoto — vivid verdicts of the State Language Centre]. DELFI lv. 29.08.2015. https://www.delfi.lv/193/politics/46391407/no-vrapa-par-titeni-no-selfija-par-pasfoto-spilgti-valsts-valodas-centra-verdikti. (Accessed 15 November 2025).

LVEK 2015 – LVEK 2015. gada 17. jūnijā lēma par ātrās uzkodas nosaukumu latviešu valodā (protokola Nr. 43) [On 17 June 2015, the Latvian Language Expert Commission (LVEK) decided on the Latvian name for the fast-food product (Protocol No. 43)].

LVK2022 – Levāne-Petrova, Kristīne, Roberts Darģis, Kristīne Pokratniece, Viesturs Jūlijs Lasmanis.Līdzsvarotais mūsdienu latviešu valodas tekstu korpuss [The Balanced Corpus of Modern Latvian] (LVK2022) CLARIN-LV digitālā bibliotēka, 2022. http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12574/84.

medium.com – Transcreation, versioning, adaptation & localisation — what’s it all about. 28 April 2020 https://medium.com/@yellowcatrecruitment/transcreation-versioning-adaptation-localisation-whats-it-all-about-b708d9a475ae. (Accessed 18 November 2025).

References

Adami, Elisabetta, Sophia Diamantopoulou and Fei Victor Lim. 2022. Design in Gunther Kress’s social semiotics. London Review of Education 20 (1). 41.

Amatulli, Cesare, Matteo De Angelis, Marco Pichierri and Gianluigi Guido. 2018. The Importance of Dream in Advertising: Luxury Versus Mass Market. International Journal of Marketing Studies 10 (1). Canadian Center of Science and Education. 71–81.

Ambote, Sintija. 2021. Plaši kritizē Covid-19 vakcinācijas reklāmas kampaņu [Covid-19 Vaccination Campaign Faces Widespread Criticism]. LSM.lv https://www.lsm.lv/raksts/zinas/latvija/plasi-kritize-covid-19-vakcinacijas-reklamas-kampanu.a413829/. (Accessed 24 August 2025).

Amos, H. William. 2020. English in French Commercial Advertising: Simultaneity, bivalency, and language boundaries. Journal of Sociolinguistics 24 (1). 55–74.

Bhatia, T.K. 1992. Discourse Functions and Pragmatics of Mixing: Advertising across Cultures. World Englishes 2 (1). 195–215.

Berra, Solvita. 2020. Ceļvedis pilsētu tekstu izpētē. [A Guide for Exploring City Texts]. Rīga: LU Latviešu valodas institūts.

Bušs, Ojārs, and Vineta Ernstsone. 2006. Latviešu valodas slenga vārdnīca [ A Dictionary of Latvian Slang]. Rīga: Zvaigzne ABC.

Cheshire, Jenny, and Lise-Marie Moser. 1994. English as a Cultural Symbol: The Case of Advertisements in French-speaking Switzerland. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 15 (6). 451–469.

Chesterman, Andrew. 2016. Memes of Translation: The spread of ideas in translation theory. (Revised edition). Amsterdam, Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Díaz-Millón, Mar, and María Dolores Olvera-Lobo. 2023. Towards a definition of transcreation: a systematic literature review, Perspectives 31 (2). 347–364. DOI:10.1080/0907676X.2021.2004177.

Dorian, Nancy C. (ed.). 1992. Investigating Obsolescence: Studies in Language Contraction and Death. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Grin, Francoise. 1994. The bilingual advertising decision. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 15. 269–292.

Haarmann, Harald. 1989. Symbolic Values of Foreign Language Use, From the Japanese Case to a General Sociolinguistic Perspective. Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Hiippala, Tuomo, Tuomas Väisänen and Hanna-Mari Pienimäki. 2024. A multimodal approach to physical and virtual linguistic landscapes across different spatial scales. In Sociolinguistic Variation in Urban Linguistic Landscapes. Studia Fennica Linguistica, vol. 24, edited by Sofie Henricson, Väinö Syrjälä, Carla Bagna and Martina Bellinzona. Finnish Literature Society, Helsinki. 158–178. https://doi.org/10.21435/sflin.24.

Ivkovic, Dejan, and Heather Lotherington. 2009. Multilingualism in cyberspace: conceptualising the virtual linguistic landscape. International Journal of Multilingualism 6 (1). 17–36.

Kachru, Braj B. 1986. The power and politics of English. World Englishes 5 (2/3). 121–40.

Kelly-Holmes, Helen. 2005. Advertising as Multilingual Communication. Basingstoke, New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kress, Gunther. 2010. Multimodality: A social semiotic approach to contemporary communication. London, New York: Routledge.

Kress, Gunther, and Selander, Staffan. 2012. Multimodal design, learning and cultures of recognition. The Internet and Higher Education 15 (4). 265–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2011.12.003.

Lamarre, Patricia. 2014. Bilingual Winks and Bilingual Wordplay in Montreal’s Linguistic Landscape. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 228. 131–151.

Lazdiņa, Sanita, and Solvita Pošeiko. 2015. Lai varētu vairāk ieinteresēt skolēnus mācību darbā, lai pašai būtu interesantāk strādāt – kā saglabāt un mācīt valodas e-gadsimtā? [In Order to Better Engage Students in Learning, and to Make the Work More Interesting for Myself – How Can One Preserve and Teach Language in the E-century?] Valodas apguve: problēmas un perspektīva. 12. Zinātnisko rakstu krājums. Liepāja: LiePA. 84–104.

Leech, Geoffrey N. 1966. English in Advertising. London: Longmans, Green and co. Ltd.

Ločmele, Gunta. 2021. Forms of Advertisement Translation in Latvia and the Latvian Language in Translation. Vertimo studijos/ Studies in Translation 14. Vilnius: Vilnius University Press. 40–55.

Ločmele, Gunta. 2024a. Laika cilpas drukātajā reklāmā – no pirmajiem tulkojumiem līdz mūsdienu adaptācijām [Time Loops in Printed Advertising: From Early Translations to Contemporary Adaptations]. Latvijas Universitātes 82. starptautiskā zinātniskā konference. Humanitāro zinātņu fakultāte. Valodniecība. Literatūrzinātne. Folkloristika. Referātu tēzes. Rīga: LU Akadēmiskais apgāds. 54–56.

Ločmele, Gunta. 2024b. Advertising in Latvian Press: from Early Editions to Modern Times. Stridon: Journal of Studies in Translation and Interpreting 4(2). University of Ljubljana Press, Slovenia. 55–78.

Ločmele, Gunta, and Vera Komarova. 2024. Gender-oriented Advertising and Peculiarities of its Translation in Latvia. Sociālo Zinātņu Vēstnesis/Social Sciences Bulletin 38 (1). Daugavpils: Daugavpils University. 74–101. https://doi.org/10.9770/szv.2024.1(4).

Martin, Elizabeth. 2002. Mixing English in French Advertising. World Englishes 21 (3). 375–402.

Mettewie, Laurence, Patricia Lamarre and Luk Van Mensel. 2012. Clins d’oeil bilingues dans le paysage linguistique de Montréal et Bruxelles: Analyse et illustration de mécanismes parallèles [Bilingual Winks in the Linguistic Landscapes of Montreal and Brussels: An Analysis and Illustration of Parallel Mechanisms]. In Linguistic Landscapes, Multilingualism and Social Change, edited by Christine Hélot, Monica Barni, Rudi Janssens and Carla Bagna. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. 201–216.

van Lier, Leo. 2004. The Ecology and Semiotics of Language Learning: A Sociocultural Perspective. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Boston. https://doi.org/10.1007/1-4020-7912-5.

Piller, Ingrid. 2001. Identity Constructions in Multilingual Advertising. Language in Society 30 (2). 153–186.

Red Pencil Advertising. 2023. The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Marketing and Advertising. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/role-artificial-intelligence-marketing-advertising. (Accessed 25 August 2025).

Selander, Staffan. 2008. Designs for learning: A theoretical perspective. Designs for Learning 1(1). 10–24.

Selander, Staffan. 2021. Designs in and for learning—a theoretical framework. In Designs for Research, Teaching and Learning, edited by Lisa Björklund Boistrup and Staffan Selander. London: Routledge. 1–22.

Wirtschaftsnachrichten. 1939. No. 214 (28.03.1939).

1 https://f150.autoblitz.lv (accessed 01.08.2025).

2 https://www.fettefordsales.com/research/f-150-overview.htm (accessed 29.04.2024).

3 https://vitabalans.fi/en/home/ (accessed 02.08.2025).

4 https://vitabalans.fi/lv/ (accessed 02.08.2025).

5 https://cdn.modera.org/original/i/kia-baltic/Brochures/EE/222070_Kia_Niro_Brochure_MY23_090522_web.pdf (accessed 05.08.2025).

6 Klubs, 2023. No. 11: 5.

7 https://www.facebook.com/kiamotorslatvija/posts/elektriz%C4%93-savu-dz%C4%ABvi-ar-jauno-kia-e-niro-brauc-l%C4%ABdz-pat-455-km-ar-vienu-uzl%C4%81di-i/3090450021034884/ (accessed 11.08.2025).

8 https://cdn.modera.org/original/i/kia-baltic/Brochures/EE/222070_Kia_Niro_Brochure_MY23_090522_web.pdf (accessed 05.08.2025).

9 https://astarte.lv/ (accessed 03.05.2024).

10 https://www.facebook.com/circleklv/videos/ (accessed 04.05.2024).

11 See, for example, https://www.facebook.com/circleklv/videos/715947980846652/

(accessed 18.08.2025).

12 https://www.fettefordsales.com/research/f-150-overview.htm (accessed 29.04.2024).

13 https://f150.autoblitz.lv/ (accessed 06.08.2025).

14 https://www.fettefordsales.com/research/f-150-overview.htm (accessed 29.04.2024).

15 https://f150.autoblitz.lv/ (accessed 07.08.2025).

16 https://www.delfi.lv/a/43193656 (accessed 07.08.2025).

17 https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=5937227556305508&id=108968472464808&set=a.117452901616365 (accessed 17.08.2025), https://pizza-time.lv/wrapi/ (accessed 20.08.2025).

18 https://www.toyota.lv/owners/warranty/toyota-relax (accessed 24.04.2024).

19 https://www.toyota.lv/owners/warranty/toyota-relax (accessed 17.08.2025).

20 https://www.facebook.com/longo.lv/ (accessed 23.04.2024).

21 Klubs 11, 2023: 7.

22 https://audiotehnika.lv/product/kef-ls60-wireless-floorstanding-speakers-pair/ (accessed 09.08.2025).

23 https://audiotehnika.lv/lv/prece/kef-ls60-wireless-floorstanding-speakers-pair/ (accessed 29.04.2024).

24 https://www.mbl-audio.ru/mbl/ (accessed 23.08.2025).

25 https://www.eckes-granini.com/en/brands/elmenhorster (accessed 23.04.2024).

26 https://spoki.lv/ (accessed 23.04.2024).

27 https://dabadaba.lv/product/malta-kafija-laiks-sarunam-250g/ (accessed 13.08.2025).

28 https://dabadaba.lv/product/saldais-upenu-aroniju-sarkanvins-laiks-sarunam/ (accessed 13.08.2025).

29 https://www.heritage-posters.co.uk/product/we-can-do-it-j-howard-miller-c1941/

(accessed 24.08.2025).