Žurnalistikos tyrimai ISSN 2029-1132 eISSN 2424-6042

2022, 16, pp. 152–173 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/ZT/JR.2022.6

Digital Transformation of Media Companies in Lebanon from Traditional to Multiplatform Production: An Assessment of Lebanese Journalists’ Adaptation to the New Digital Era

Ali El Takach (Corresponding author)

Dean, Faculty of Mass Communication and Fine Arts, Al Maaref University, Beirut, Lebanon

Associate Professor, Faculty of Information, Lebanese University, Beirut, Lebanon

Email: ali.takach@mu.edu.lb

Farah Nassour

Journalist, An-Nahar Newspaper, Beirut, Lebanon

Hussin Jose Hejase

Consultant to the President, Professor of Business Administration, Al Maaref University, Beirut, Lebanon

Abstract. This research aims to assess Lebanese media organizations’ and journalists’ readiness and adaptation to the new digital era requirements. Journalism has always been affected by technology. Adopting new information and communications technology has obliged changes in journalistic practices and led to new business models and journalistic practices. For example, implementing Newsroom Computer Systems (NRCs) in media companies has led to radical changes in the departments of these organizations, and in particular in the newsrooms. The journalists in newsrooms are the human factor that is considered an essential element in this change. It touched on the depths of productivity and the mode of journalistic work. In the new era of media convergence, journalists are called upon to follow this trend (modern journalism) and become more versatile, where their work becomes streamlined and redesigned. The new and more flexible journalistic practices emerging in newspaper and television production, in combination with online journalism, have a profound effect on the role of journalists and their competencies requirements. Having multi competencies is explained by mastering the basic rules (writing, etc.) in the journalism profession and digital knowledge related to this profession (visualizing data, using the digital tools necessary for work, etc.).

This study uses quantitative, descriptive, and deductive approaches supported by a structured survey questionnaire. The sample in this research constituted 96 respondent journalists selected conveniently. Data were analyzed descriptively and reported in charts for clarity. Results show that from an overall analysis, Lebanese media organizations and journalists are moderately prepared to deal with the digital era requirements. Most of the research variables scored between 40 to 50% in terms of preparedness and functionality during the digital transformation era. The research implications show that in Lebanon, as elsewhere in the media industry, the human factor’s digital culture plays an essential role in the advancement of the companies towards the digital environment. In the Lebanese organizations’ case, the economic and monetary crisis factors besides the human factor, have affected the technical implementation and the digital transformation of the media outlets. In this media landscape, the role of academic institutions (i.e., universities and research centers) must be proactive to define the new set of digital and journalistic skills required and needed to enhance the transformation towards the digital multitasking and cross-platform profiles needed to adopt the digital mindset effectively and efficiently.

Keywords: Journalism, Digital era, Digital tools, Multi-skills, Digitization, Cross-platform production, Media industry.

Received: 2022/12/15. Accepted: 2023/01/30

Copyright © 2022 Ali El Takach, Farah Nassour, Hussin Jose Hejase. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence (CC BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

Reaching digital transformation needs three phases “digitization, digitalization, and digital transformation” (Verhoef, Broekhuizen, Bart, et al., 2021, p. 891). The first “is the encoding of analog information into a digital,” the second “describes how IT or digital technologies can be used to alter existing business processes,” and the third “is the most pervasive phase, and describes a company-wide change that leads to the development of new business models format” (p. 891). Also, digitization brought changes to the process of producing media content. Doyle (2015) posits that media organizations have migrated from an individual sector (in linear distribution) to a multi-platform delivery framework where such organizations have become content providers on digital multi-platforms. The resultant impact leads to an abundance of content and an increase in productivity potential in the media industry, deploying cross-platform content to an audience that is more personalized and interactive (ibid).

Adopting the transition to cross-platform distribution has not been similar across media organizations (Santos, Medeiros, Lenzi, and Ghinea, 2019). This transition differed from one type of medium to another and obviously from one country to another (Manyika, Lund, Bughin, et al., 2016; Santos et al., 2019).

In Lebanon, as everywhere in the world, the media are witnessing a crisis of adaptation to the digital environment. Such was the case of the newspaper “As-Safir” which failed to evolve and disappeared. The same happened to “one of the oldest press houses in the country, Dar Assayad,” which unexpectedly announced the interruption of all its activities (Khalifeh, 2018a, b, para 3). Others followed suit; the newspaper “al-Anwar,” and the daily “al-Hayat” newspaper that has closed its office in Beirut (ibid, para 3,4). Media companies (newspapers and television channels) face the challenge of positioning and restructuring. This challenge arose as a result of economic issues essentially linked: on the one hand, to the inevitable transformation to digital, and on the other hand, to the drop in advertising expenditure in favor of the digital advertising market (Palmer, & Koenig‐Lewis, 2009; Khalifeh, 2018a, b). In addition, the digital segment experienced significant growth and has attracted 20 to 25% of the advertising budgets (Commerce du Levant, 2017). The Web will continue to gain market share to the detriment of television, but above all, the written press, whose budget dropped by 30 to 40% in 2017 (Commerce du Levant, 2017).

In this context, some titles will no doubt disappear, and others will have to reinvent themselves to move into the digital age. The digital transformation imposes radical changes to the media (Vial, 2019), and newspapers need to start the digital transformation and inject the necessary capital (De la Boutetière, Montagner, and Reich, 2018).

Based on the above facts, it is essential to study how newspaper companies adapt to digital transformation. Moreover, presenting the case study in Lebanese media companies would be of great importance due to the absence of evaluative studies within these companies in Lebanon.

This paper will present a clear picture concerning the scale of transformation in the press companies in Lebanon, as well as the journalist’s adaptation to the new era since the profession of journalism and its ethics have changed with the digital transformation (Foucault, 2000; De la Boutetière, Montagner and Reich, 2018).

Research Questions

1. To what extent the media outlets in Lebanon have digitally transformed?

2. How did the Lebanese journalists adapt to the new digital era?

Materials and Method

This research uses a quantitative approach with a positivist philosophy. According to Hejase & Hejase (2013), “Positivism is when the researcher assumes the role of an objective analyst, is independent, and neither affects nor is affected by the subject of the research” (p. 77). Moreover, the study used a deductive approach in which data were collected using a structured questionnaire.

To answer the central questions of this paper, the researchers adopted the survey method. They distributed (by Google form) a questionnaire to Lebanese journalists working in different types of media organizations. The number of journalists who completed this questionnaire was 96. However, to assess the reliability of the sample size, and according to Hashem et al. (2022) and Younis et al. (2022), using Hardwick Research’s (2022) published resources on the subject provides a statistically significant reliability figure. Table 2 shows that in the case of a general population of journalists in Lebanon of ~ 5,000, a sample of 96 journalists, and a confidence level of 95% [α=5%], an adequate reliability of 10% is obtained (see Table 1). The sample size varies between 75 and 100 though nearest to 100. Therefore, the resultant sample size of 96 would be about 10% ± 1% at the 95% confidence level. Such reliability is appropriate for this exploratory study.

Table 1: Sample reliability at 95% confidence

|

Statistical Reliability at the 95% Confidence Level |

|||||||

|

|

Population |

||||||

|

Sample Size |

100 |

500 |

1000 |

5000 |

10000 |

100000 |

1 Mill+ |

|

30 |

±14.7% |

±17.1% |

±17.3% |

±17.6% |

±17.7% |

±17.8% |

±17.9% |

|

50 |

±9.7% |

±13.1% |

±13.5% |

±13.8% |

±13.9% |

±14.0% |

±14.1% |

|

75 |

±5.6% |

±10.4% |

±10.9% |

±11.3% |

±11.4% |

±11.5% |

±11.6% |

|

100 |

|

±8.8% |

±9.3% |

±9.7% |

±9.8% |

±9.9% |

±10.0% |

Source: Hardwick Research, 2022.

Questionnaire design

This study is exploratory as mentioned earlier; therefore, the survey questionnaire consists of 10 multiple-choice questions that focus mainly on journalists’ digital skills in media organizations, their behavior toward new digital tools, their knowledge of these tools, and their uses.

Data analysis

This research used descriptive analysis to generate the appropriate data to answer the main research questions. According to Hejase & Hejase (2013a), “descriptive statistics deals with describing a collection of data by condensing the amounts of data into simple representative numerical quantities or plots that can provide a better understanding of the collected data” (p. 272). Hence, frequencies and percentages were used and depicted in figures for clarity.

Results and Findings

Demographics

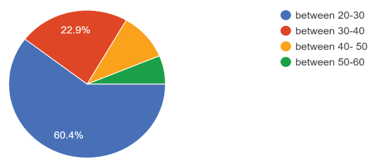

Age. Figure 1 shows that 60.4% of the respondents are 20 to 30 years old, 22.9% are 30 to 40 years old, and the remaining 16.7% include the higher age categories of 40 to 50 and 50 to 60 years old. So, the results lead to an average age of 31 years.

Figure 1. Journalists’ age distribution

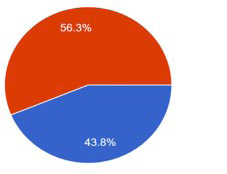

Type of Work: Media categories. Respondents were asked about the category of their organizations being traditional or digital. Results in Figure 2 show that 56.3% of journalists worked in digital media with roles in social media, and websites, and the other 43.7% worked in traditional media companies, i.e., TV, radio, and newspapers.

Figure 2. Media categories per journalists

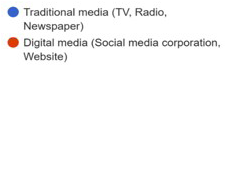

Respondents’ fields of study

Figure 3. Lebanese journalists’ field of study

Figure 3 provides strong evidence that 75% of the journalists who responded to this question majored in fine arts and journalism, followed by 9.4% of the respondents majoring in business administration. The third group of journalists majored in humanities and constituted about 3%, while five (5) other categories of majors constituted 12.6%. Therefore, most of the sample are journalists with an appropriate background, while the remaining could be journalists by practice whose experience is from the job.

Status and Stance towards Digitalization

Journalists:

Journalists’ adaptation to digital journalism

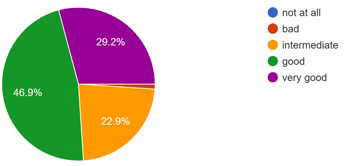

About 47% of journalists consider themselves to have a good level of adaptation to the digital environment (Figure 4), 29% find themselves very well adapted, and 22% are moderately adapted.

Figure 4. Lebanese journalists’ adaptation to new digital journalism

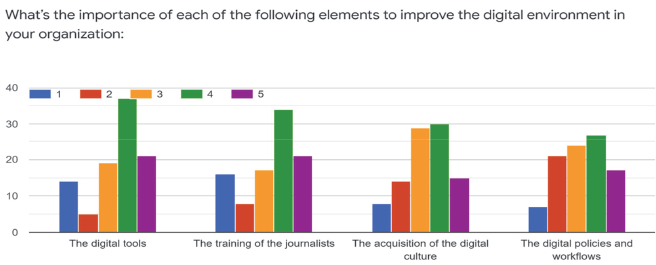

Self-development of Lebanese journalists’ digital skills

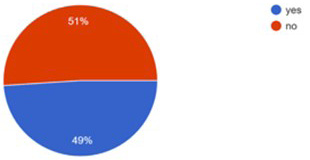

Results of the survey shown in Figure 5 indicate that 51% of journalists pursue their development by acquiring the necessary digital skills. However, a significant 49% do not. Such a result may clearly show that there is a digital gap characterizing the journalist who shortly they have to deal with advanced notions of digital journalism. From another perspective, it also shows that there is no formal digital culture to encourage self-development for all employees besides journalists.

Figure 5. Self-development of Lebanese journalists’ digital skills

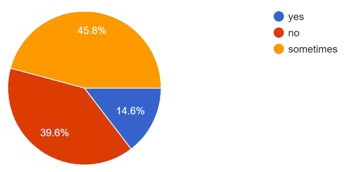

Work stress due to digital tasks

Sometimes journalists express feelings of being under pressure. Results shown in Figure 6 expose that about 46% of journalists feel stressed when performing digital tasks at work, around 15% suffer from this pressure, while about 40% feel no pressure at all. Considering the actual level of digital skills exposed in this study, such feelings of stress (pressure) are not surprising.

Figure 6. Digital tasks and work stress

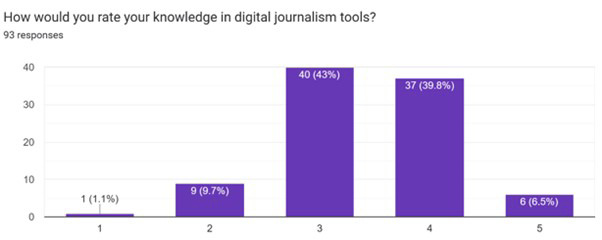

Journalists’ knowledge of digital journalism tools

As Figure 7 shows, 46.3% (grouping agree (4) and strongly agree(5)) of the journalists believe they know well digital journalism tools, 43% of the journalist said they have moderate knowledge, and 10.8% have weak knowledge.

Figure 7. Lebanese journalists’ self-assessment of digital knowledge

Organizations:

Organizational roles in preparing their journalists to deal with digital journalism

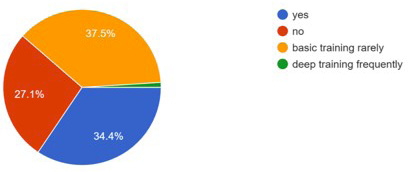

Training. Figure 8 shows that about 34% of journalists confirmed that their organizations train them in digital technologies and tools needed to comply with duties in digital journalism. But, about 38% admit to receiving basic training rarely, while about 27% had no training at all from their organizations. Worth mentioning that about 1% of journalists receive deep training frequently.

Figure 8. Digital tools training in the Lebanese media organizations

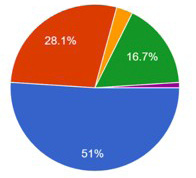

Organizational status considering media digitization

Results (Figure 9) show that 51% of journalists considered that the organization where they work is advanced in the digital environment. While about 17% claim they have some plans, and 28% said the organization they work for has recently started planning to attend this environment. Nevertheless, around 4% of the organizations have no plans, and a few, consider digitization a bad choice.

Figure 9. Organizational status considering media digitization

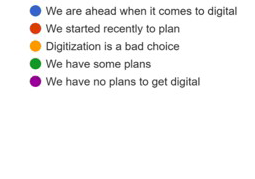

Importance of elements needed to improve the digital environment

Figure 10 shows that the bars in the diagram represent the height (percentage) of importance as follows: 1: least important to 5: Most important. Therefore, results show that when grouping “important (4) and most important (5),” about 59% of the journalists see that the most important element is the “digital tools.” The second element in terms of importance is the “training of the journalists” with about 53% agreement by the respondents. The third element with about 44% in terms of importance, is the “acquisition of digital culture,” and finally, in the same rank is the element “digital policies and workflows” with 44%.

Figure 10. Importance of elements needed to improve the digital environment

Discussion

When a journalist can define digital tools, it means that he/she has a minimum required digital knowledge concerning the digital era. This study shows that 43 out of 96 (46.3%) journalists know to define digital tools. Such a result indicates that the sample of Lebanese journalists has a gap in digital knowledge. This comes from different possible causes among those academic institutions that may not be preparing their students to possess the theoretical and practical foundations of digital knowledge requirements in an era where digital journalists are recruited.

Most newly graduated media practitioners face a professional environment that does not fit their academic preparation and expectations. Maryville University (2023), in a Blog paper, posits that “Revolutionizing global commerce and communication seemingly overnight, the internet has also fundamentally changed how journalists and media outlets operate. Old-school journalism outlets have found it difficult to adjust, but newer types of journalism have flourished in a media landscape that’s almost unrecognizable from a few decades ago” (para 6). Also, academic institutions must provide students with digital cultures to change their mindsets and orient them toward the digital one.

Findings show that 60.4% of the journalists surveyed are in the 20-30 age group. Therefore, based on the abovementioned facts about digital knowledge, the study presents evidence that there is a gap in the academic preparation reflecting possible classical curricula in the respondents’ respective universities. Besides the academic qualifications requirements, having a digital culture comes from the inner being of each journalist. Concerning this notion, the survey shows that organizational digital culture is not yet considered a game key in the digital environment since 44% of the respondents declared that their organizations did not consider digital culture a priority. Therefore, not having a mature digital culture is a concern about the organizations’ sustainability. According to Jack Bray, Content Marketing Manager at GDS Group, “There are several reasons why a digital culture should matter to an organization, but centrally because it supports digital transformation” (para 2). Bray continues, “Consequently, a digital culture impacts corporate culture just as much as business models for the following facts: Breaks hierarchy, speeds up work, encourages innovation, attracts new-age talent, retains the current workforce, allows a collaborative and autonomous workplace, and increases employee engagement by allowing them to bring their voice and opinions to help create an impact” (ibid, para 2-3). In fact, employee engagement or journalist engagement fosters Foucault’s (2000) fourth type, i.e., technologies of the self which “permit individuals to effect by their means, or with the help of others, a certain number of operations on their bodies and souls, thoughts, conduct, and way of being, to transform themselves to attain a certain state of happiness, purity, wisdom, perfection, or immorality” (p. 225).

Bughin (2017) posits that “Netflix CEO Reed Hastings once explained in a famous presentation that his company’s culture was built on self-driven, high-performing individuals” (para 1). In addition, Bughin asserts that “while a strong digital strategy is critical, you need a culture conducive to its execution. That’s particularly important when you pursue the strategy of becoming a “fast follower”—one of two approaches that tend to produce digital winners” (para 2). When reflecting on Netflix and the research done by Bughin, one can easily conclude that the journalists needed today to seek continuous preparation and training either through their organizations or by taking self-initiatives. Consequently, this study considered the above and found that 47% of respondent journalists have a good level of adaptation to the digital environment, and 51% of journalists pursue their development by acquiring the necessary digital skills. However, a significant 49% do not. Also, about 34% of journalists confirmed that their organizations train them in digital technologies and tools needed to comply with duties in digital journalism. But, about 38% admit to receiving basic training rarely, while about 27% had no training at all from their organizations. Possible causes for not having higher numbers include organizations not having a mature digital culture, journalists having high daily workloads, organizations not having preplanned training programs for their journalists’ development, and the lack of responsiveness toward the fast changes in the media industry.

The previous section discussed the status of the Lebanese respondent journalists. In summary, the following applies: When we discuss the human factor in the advancement of the media organization to the digital era, the main issue is how to break with the classical production models; the generation of printed newspapers and television media producers, lack the resilience and the agility to shift from, the so-called “The golden age” of the classical media, into a rapid and instantaneous and multi-skills model, of the new media. Hodali (2019) contends that “With 10 private dailies in three languages and over 1,500 weekly or monthly magazines, Lebanon produces almost half of the Middle East’s periodicals, according to a “Reporters Without Borders” study. In addition, there are also nine TV stations and around 40 radio stations. Lebanon has a diverse media landscape. More and more media companies are betting on the expansion of digital media but the strategy remains unclear” (para 9-10).

Melki, Dabbous, Nasser, et al. (2012) assert that Lebanon is witnessing a continuous internal debate about the digital gap within media organizations. Moreover, the authors posit that “The current business model that Lebanese media rely on has not been affected by digitization. It still relies on partisan and foreign financial support, in addition to the traditional business models which mainstream media have used for decades” (p. 7). Thus, we may discuss the economic factor and the organizational management support.

Concerning the economic factor, many media organizations have struggled to have a successful digital transition, for economic reasons, as advertising revenue (essential to fueling the traditional organization) has fallen in favor of digital (Palmer & Koenig‐Lewis, 2009). Many press outlets (across the world) have either closed fully or have been content with their digital version, which is less expensive in terms of expenditure. And the lack of income has directly impacted the power to implement new digital editorial systems in the media industry and left journalists in these organizations out of touch with digital tools. One has not to forget that Lebanon, since the end of the year 2019, has been suffering from an economic crisis (Rkein et al., 2022), which has also affected the written press, since the cost of printing has risen and has increased the price of the newspaper and lower sales. But the organizations that have reached their digital course, undoubtedly receive the external feed, whether it is political money or businesspersons’ support.

Nevertheless, in the context of the local crisis in Lebanon, adopting new techniques and equipment in the digital era is now expensive for some organizations that prefer to work as much as possible with what is available rather than paying for the installation of new systems. This reality prevents efficient and effective production and puts more journalists under pressure. This study shows that 47% of journalists consider themselves to have a good level of adaptation to the digital environment, about 45.8% of the journalists feel stressed when performing digital tasks at work, and about 15% suffer from this pressure.

Also, the survey shows that 51% of journalists considered that the organization where they work is advanced in the digital environment. While about 17% claim they have some plans, and 28% said the organization they work for has recently started planning to attend this environment.

These numbers have two indicators. Almost half of the organizations found their digital path, but 28% had recently started their plans at this stage, and this proves that a consistent number of media organizations in Lebanon are still not on the digital path. And, we cannot confirm for sure, that all 51% of the respondent journalists know how to classify an organization in the digital era.

The above is confirmed by 46.3% of the journalists who believe they know digital journalism tools well, and 43% of the journalist have moderate knowledge.

Hodali (2019) posits that “More and more media companies are betting on the expansion of digital media but the strategy remains unclear” (para 10). Such a blurred strategy affects the implementation of best practices in media organizations, especially what concerns their human capital’s training and development. This study shows that about 34% of journalists confirmed that their organizations train them in digital technologies and tools needed to comply with duties in digital journalism. Consequently, 51% of the respondent journalists pursue their development by acquiring the necessary digital skills. Irrespective if there is a group in common, who is either trained by their organizations or who is seeking self-development, there are about 38% of respondent journalists admit receiving basic training only, and a minimum of 1% receive deep training.

Conclusion

Most Lebanese media organizations are struggling to adapt to a fully digital transformation. They are moving forward slowly by doing little change that doesn’t cost money, especially during the current economic crisis. So the economic factor is as significant as the human factor since media organizations are constrained to certain economic limits, especially since the price of digital editorial systems is an influential factor in adopting a system or another (Mangon, 2018; Khalifeh, 2018a, b).

This research addressed two questions, the first addressed “To what extent the press companies in Lebanon have digitally transformed?”, and the second assessed “How did the Lebanese journalists adapt to the new digital era?” As discussed earlier, Lebanese organizations continue the quest to get out of their troubles as they show gaps in their transformation process. The majority of such organizations continue to search for their appropriate business models. That is illustrated by 59% and 53% of the respondents who asserted that the most significant elements in their organizations, toward achieving digital transformation, are “digital tools” and “training of the journalists,” respectively. They left behind the more strategic elements illustrated by equal weights of about 44% of them choosing the “acquisition of digital culture,” and the “digital policies and workflows.” In addition, 51% of the respondents claimed their companies are advanced in the digital environment even though about 17% claim they have some plans, and 28% said the organization they work for has recently started planning to attend to this environment. Those facts indicate there are discrepancies that urge Lebanese press companies to seriously define their value propositions, choose appropriate business models, decide on how they will deal with their journalists, acquire necessary technologies to move closer to the digital era, and sustain their stance. Such a fact is a recurrent topic among Lebanese researchers who try to discuss the status of the Lebanese media (Melki, Dabbous, Nasser, et al., 2012; Khalifeh, 2018 a, b). As for the second question related to Lebanese journalists and their efforts to adapt to the new digital era, the results show that, on average, Lebanese journalists are not yet prepared to deal comfortably with the skills and competencies required to carry out digital tasks successfully. The aforementioned is in agreement with Daher, El Zir, and Jaber (2022) who asserted that “Unfortunately, the Lebanese workforce is ill-equipped to thrive in a digital economy. Without the right skills, Lebanon may not benefit from the opportunities disruptive technologies and digital firms offer” (para 4).

It is worth mentioning that digital transformation is a whole process (Verhoef, Broekhuizen, Bart, et al. (2021) that touches all organizational levels, especially the journalists and their work. That’s why it’s a bit hard to change the mentality of traditional journalists and embrace them in a whole new environment with tools of digital media and integrate them into their daily journalistic work. However, organizations must cultivate the needed competencies capitalizing on the strong sense of self-development that 51% of the respondent journalists have shown. Media organizations and newsrooms need to be proactive such that these entities must seek partnerships with universities in such a manner to jointly design an innovative journalism curriculum that embodies digital media besides other competencies that are considered traditional (writing, editing, etc). The aforementioned shall support the new journalism or Online Journalism. Saltzis and Dickinson (2008) posit that “As more and more news organizations have developed a presence on the Internet, a new form of journalism has appeared” (p. 4). In addition, Pavlik (2001) hails “from online journalism as “potentially a better form of journalism” as it can “re-engage an increasingly distrusting and alienated audience” (p. xi). Pavlik’s statement about the distrusting and alienated audience applies to the Lebanese audience as well, a fact supported by Hejase and Hejase (2013b), Mangon (2018), and Hejase, Hejase, and Fayyad-Kazan (2020). Consequently, Lebanese media outlets started transitioning to Alternative Media Outlets. El Sherif, Bahnam, Mikhael, et al. (2021) define them as “Media sources that differ from established or dominant types of media, such as mainstream media or traditional media” (p. 4). Downing (2001) stressed the difference in terms of their “content, production, or distribution.” In addition, El Sherif et al. assert that “alternative media are small and/or nascent media platforms, mostly online, that offer an alternative narrative to mainstream media” (p. 4). However, besides such development, this work strongly recommends that young journalists have to be cultivated and armed with multitasking competencies to support and sustain Lebanese media organizations and to strengthen the role of new newsroom functions. Such an endeavor is possible by qualifying journalists to own all the knowledge and adopt the adequate culture; to be ready to learn the digital tools practically. In parallel, a serious effort is needed to culture the current practitioner journalists about the priority of digital skills and having the appropriate thinking necessary to carry out digital journalism functions.

Limitations of the study

This work has its limitations starting with the small sample size that limits the generalization of the findings. This work being exploratory research, the findings act as insights into the next stage of future research that may depend on a larger sample size and a more comprehensive survey questionnaire in content and distribution. Moreover, selected journalists were not stratified to represent the different categories existent besides the newsrooms therefore, future research must look into that as well.

Recommendations

Given that the media industry is evolving very fast, Lebanese media organizations are to step into the actual digital era, and enhance the full-digital transformation process, since most of them are lagging. Media organizations must establish a clear strategy to implement an integrated newsroom, achieve digital production, raise productivity, make the tasks go faster with central observation and tracking, and bring less pressure to the journalists. But first, it’s inevitable to train them continuously and cultivate journalists fit to function within the digital era.

This research is an eye-opener to newsroom directors and media organizations’ policymakers. In addition, researchers in the field are encouraged to carry out more comprehensive research, create a platform to support academic institutions’ efforts to develop their curricula, and motivate professional journalists to engage in self-development efforts.

References

Bray, J 2022, May 18, ‘What is Digital Culture?,’ GDS Group. [Online]. Available at: (Accessed: 11 January 2023)

Bughin, J 2017, ‘Digital success requires a digital culture,’ McKinsey & Company. [Online]. Available at: (Accessed: 11 January 2023)

Commerce du Levant. (2017). Pierre Choueiri : ‘La presse doit entamer sa transition digitale’ -. [online] Available at: https://www.lecommercedulevant.com/article/27318-pierre-choueiri-la-presse-doit-entamer-sa-transition-digitale- (Accessed: 21 January 2023).

Daher, M, El Zir, A and Jaber, A 2022, March 14, ‘Skilling Up Lebanon: An opportunity to lower unemployment rates in Lebanon amid a major financial crisis?’{Blog] World Bank [Online]. Available at: (Accessed: 13 January 2023).

De la Boutetière, H, Montagner, A and Reich, A, 2018, ‘Unlocking success in digital transformations,’ McKinsey & Co. [Online]. Available at: (Accessed: 5 January 2023).

Downing, J 2001, ‘Radical Media,’ Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications

Doyle, G 2010, ‘From Television to Multi-Platform. Convergence,’ The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, vol. 16, no. 4, pp. 431–449. DOI:10.1177/1354856510375145.

Doyle, G 2015, ‘Multi-platform media and the miracle of the loaves and fishes,’ Journal of Media Business Studies, vol. 12, no. 1, pp.49–65. DOI:10.1080/16522354.2015.1027113.

El Sherif, H, Bahnam, L, Mikhael, R, Thebian, A and Kaoukji, D 2021, ‘Media and Information Landscape in Lebanon,’ Interview [Online]. Available at: https://internews.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Media-and-Information-Landscape-in-Lebanon.pdf (Accessed: 14 January 2023).

Foucault, M 2000, ‘Ethics: Subjectivity and Truth: Essential Works of Foucault 1954–1984,’ Volume 1. Penguin Books.

García Avilés, JA, León, B, Sanders, K and Harrison, J 2004, ‘Journalists at digital television newsrooms in Britain and Spain: workflow and multi‐skilling in a competitive environment,’ Journalism Studies, vol. 5, no. 1, pp.87–100. DOI:10.1080/1461670032000174765.

Hardwick Research 2022, ‘Determining Sample Size. Hardwick Research Resources,’ [Online]. Available at: https://www.hardwickresearch.com/resources/determining-sample-size/ H (Accessed: 5 January 2023).

Hashem, M, Sfeir, E, Hejase, HJ and Hejase, AJ 2022, ‘Effect of Online Training on Employee Engagement during the COVID-19 Era,’ Asian Business Research, 7(5), pp. 10-40. https://doi.org/10.20849/abr.v7i5.1294

Hejase, AJ and Hejase, HJ 2013a, ‘Research methods: A practical approach for business students’ (2nd ed.). Philadelphia, PA, USA: Masadir Inc.

Hejase, AJ and Hejase, HJ 2013b, ‘Confidence in News Media: Exploring Lebanon,’ Global Media Journal, Arabian Edition, vol. 2, no. 1-2), pp. 47-67.

Hejase, HJ, Hejase, AJ, & Fayyad-Kazan, H 2020, ‘News Media in Lebanon: Quantifying the Confidence Using Parametric and Non-parametric Testing,’ Saudi J Bus Manag Stud, vol. 5, no. 11, pp. 512-529. DOI: 10.36348/sjbms.2020.v05i11.001

Honda, D 2019, July 5, ‘Lebanon’s media landscape - struggling with digitalization and media freedom,’ [Online]. Available at: https://akademie.dw.com/en/lebanons-media-landscape-struggling-with-digitalization-and-media-freedom/a-48635698 (accessed: 12 January 2023).

Khalifeh, P 2018a, October 29, ‘La presse écrite Libanaise à l’agonie,’ [Online]. Available at: https://www.middleeasteye.net/fr/opinion-fr/la-presse-ecrite-libanaise-lagonie [Accessed 13 December 2022].

Khalifeh, P 2018b, November 11, ‘Pressing issue: Lebanon’s print media is dying,’ Middle East Eye [Online]. Available at: https://www.middleeasteye.net/fr/news/lebanons-written-press-dying-1835548710 (Accessed: 13 January 2023).

Mangon, S 2018, October 15, ‘The quest for better information: Inside Lebanon’s media labs,’ [Online]. Available at: https://www.synaps.network/post/emerging-media-startups-lebanon (Accessed: 13 January 2023).

Manyika, J, Lund, S, Bughin, J, Woetzel, J, Stamenov, K and Dhingra, D 2016, March, ‘Digital Globalization: The New Era of Global Flows,’ The McKinsey Global Institute (MGI) [Online]. Available at: (Accessed: 13 January 2023).

Maryville University 2023, ‘The Rise of Digital Journalism: Past, Present, and Future,’ [Online]. Available at: https://online.maryville.edu/blog/digital-journalism/ (Accessed: 11 January 2023).

Melki, J, Dabbous, Y, Nasser, K and Mallat, S (lead reporters), Shawwa, M, Oghia, M, Bachoura, D, Shehayeb, Z, Khozam, I, Hajj, A, Hajj, S (reporters) 2012, ‘Mapping Digital Media: Lebanon’ Open Society Foundation [Online]. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/335975474_Mapping_Digital_Media_Lebanon

Palmer, A and Koenig‐Lewis, N 2009, ‘An experiential, social network‐based approach to direct marketing,’ Direct Marketing: An International Journal, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 162-176. https://doi.org/10.1108/17505930910985116

Pavlik, JV 2001, ‘Journalism and New Media,’ New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Rkein, A, Hejase, HJ, Rkein, H and Fayyad-Kazan, H 2022, ‘Bank’s Financial Statements as a Source for Investors’ Decision-making: A Case from Lebanon,’ Academy of Accounting and Financial Studies Journal, vol. 26, no. 6, pp. 1-14.

Saltzis, K and Dickinson, R 2008, ‘Inside the changing newsroom: journalists’ responses to media convergence,’ Aslib Proceedings, vol. 60, no. 3, pp. 216-228. DOI:10.1108/00012530810879097

Santos, É, Medeiros, B, Lenzi, A and Ghinea, G 2019, ‘Journalistic newsrooms in a context of convergence: an exploratory comparative study in Brazil, Costa Rica, and England,’ Communication & Innovation, vol. 20, no. 43. DOI:10.13037/ci.vol20n43.5933.

Verhoef, PC, Broekhuizen, T, Bart, Y, Bhattacharya, A, Dong, JQ, Fabian, N and Haenlein, M 2021, ‘Digital transformation: A multidisciplinary reflection and research agenda,’ Journal of Business Research, vol. 122, pp. 889-901. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.09.022

Vial, G 2019, ‘Understanding digital transformation: A review and a research agenda,’ The Journal of Strategic Information Systems, vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 118-144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsis.2019.01.003.

Younis, JA, Hejase, HJ, Dalal, HR, Hejase, AJ and Frimousse, S, 2022, ‘Leaderships’ Role in Managing Crisis in the Lebanese Health Sector: An Assessment of Influencing Factors,’ Research in Health Science, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 54-97. http://dx.doi.org/10.22158/rhs.v7n3p54