Respectus philologicus eISSN 2335-2388

2019, vol. 35(40), pp.11–29 DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15388/RESPECTUS.2019.35.40.01

Strategies of Legitimisation and

Delegitimisation in Selected American

Presidential Speeches

Zorica Trajkova

Ss. Cyril and Methodius University

Department of English Language and Literature

Boul. Goce Delcev 9A, Skopje, Macedonia

Email: trajkova_zorica@flf.ukim.edu.mk

ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2346-978X

Research interests: pragmatics and discourse analysis

Silvana Neshkovska

St. Kliment Ohridski University in Bitola

Faculty of Education

Ul. Vasko Karangeleski bb., 7000 Bitola, Macedonia

Email: silvana.neskovska@uklo.edu.mk

ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4417-7783

Research interests: pragmatics and discourse analysis

Summary. Politicians invest a lot of time and effort to win elections and present themselves in the best possible manner. They use language strategies to present and legitimise themselves as the right choice. And if they are the right choice, then their opponent is obviously not, so while they are trying to acclaim themselves and their political party, they use strategies to delegitimise and attack their opponents and the policy they represent.

This paper aims to conduct a critical discourse analysis of the speeches of the two main political opponents in the last elections in the USA, Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton. The research gives an insight into the manipulative function of language and covers two aspects: the lexical-semantic and pragmatic aspect and is based on the supposition that the strategies politicians use while talking about themselves and describing their opponents differ. As expected, they use more positive terminology to talk about themselves and their policies, and negative terminology to criticise the opponent’s policy. They also employ different pragmatic strategies, such as intensifiers and inclusive pronouns, to involve the audience into the discourse and convince them in their arguments. Finally, although carried out on a relatively small corpus, the analysis gives an insight into the language techniques employed by politicians to legitimise themselves and delegitimise their opponent and thus win the elections.

Keywords: political discourse, presidential elections, (de)legitimisation, lexical-semantic analysis, pragmatic analysis.

Submitted 10/12/2018 / Accepted 18/02/2019.

Įteikta 2018 12 10 / Priimta 2019 02 18

Copyright © 2019 Zorika Trajkova, Silvana Neshkovska. Published by Vilnius University Press

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License CC BY-NC-ND 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium provided the original author and source are credited.

Zorica Trajkova is an Associate Professor of English Linguistics at the Department of English Language and Literature at Ss. Cyril and Methodius University in Skopje. She is a co-author of “Speech acts: requesting, thanking, apologizing and complaining in Macedonian and English” (Akademski Pechat, Skopje, 2014). She has published internationally in linguistic journals and volumes (e.g. “Research in English and Applied Linguistics REAL Studies 8. Graduate Academic Writing in Europe in Comparison”. Cuvillier Verlag, Göttingen, Germany, 2015; International Journal of Education TEACHER, 2017, 2018; Lodz Papers in Pragmatics, 2018, etc.).

Silvana Neshkovska is an Assistant Professor at the Faculty of Education at St. Kliment Ohridski University in Bitola. She has published research papers on expressing verbal irony and the speech act of expressing gratitude in various scientific journals (Horizons A, 2017; “Linguistics, Culture and Identity in Foreign Language Education”, 2014; Teacher International Journal (IJET), 2017; International Journal of Language and Linguistics (IJLL), 2015; International Journal of Scientific Research and Publications, 2015, etc.).

Introduction

Presidential elections are important for every country’s transition and development and the focus of the whole nation during election time is on the main presidential candidates. Therefore, political parties invest a great deal of energy and finances to do the best presentation of their candidates to the electorate and hope to win the elections. They even hire political and language experts to prepare or to help the candidate prepare their speeches or arguments in debates. They are very careful in selecting the appropriate language with which their candidate will present themselves and will also comment on their opponents and the policies they represent. Of course, as it is the case with all societies and elections, politicians always talk about themselves and their party in superlative but use rather negative and critical language to describe the opposing party and their opponent. So, they use arguments to justify their own behaviour, or legitimise it, and to criticise their opponents’ or delegitimise it. Reyes (2011: 782) also defines the act of legitimisation as “the process by which speakers accredit or license a type of social behavior” and “in this respect, it is a justification of a behavior (mental or physical)”. He adds that the act of legitimizing or justifying is related to a goal, which, in most cases, seeks our interlocutor’s support and approval, which can be motivated by different reasons: to obtain or maintain power, to achieve social acceptance, to improve community relationships, to reach popularity or fame, etc. (2011: 782). Cap (2008: 39) also states that legitimisation is a principle discourse goal sought by political actors. Legitimisation deserves special attention in political discourse because it is from this speech event that political leaders justify their political agenda to maintain or alter the direction of a whole nation and, in the case of US leaders, the entire world (Reyes 2011: 783).

Van Dijk (1997: 18) defines political discourse as a prominent way of ‘doing politics’. It is a genre in which political actors speak publically and aim to promote political agendas (Reyes 2011: 783). These speeches are legally legitimised ‘by its authoritative source and formal context’ (Rojo, Van Dijk 1997: 530). The political actors have been given authority and power, which they exert to influence the audience into accepting their standing points concerning different social issues by justifying their actions and attacking the ones of their opponents. Therefore, political discourse constitutes an example of persuasive speech, to a certain extent organized and conceived to legitimise political goals (Cap 2008).

Therefore, this paper presents strategies of legitimisation and delegitimisation used by the two presidential candidates, Donald Trump and Hilary Clinton, and their linguistic means of realization in discourse. More precisely, the aim of this paper is to conduct a Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) of selected speeches of the two main political opponents in the last elections in the USA. Many authors (Jensen et al. 2016; Darweesh, Abdullah 2016; Savoy 2018; Liu, Lei 2018, etc.) have done Critical Discourse Analysis of the speeches these two candidates produced during their presidential campaigns.

The corpus for this analysis consists of two speeches: the speech of Donald Trump (the New York City speech from 22 June 2016, 3328 words overall; Trump 2016) and the speech of Hillary Clinton (delivered in Ohio State on 11 October 2016, 4787 words; Clinton 2016) during the last presidential elections campaigns. Trump was nominated from the Republican party (right-wing party) and Clinton was representing the Democrats (left-wing party).

We have decided to analyse these two specific speeches, since we realised they mark specific turning points in the campaigns of the two candidates. The Republican presidential nominee, Donald Trump, oversaw a shake-up of his campaign staff, so, in New York, he tried to refocus his campaign with a speech attacking his Democratic rival, Hillary Clinton1. On the other hand, since for much of the summer, Clinton’s speeches and television ads were overwhelmingly critical of Trump, she has decided to change the tone of her campaign. Just as Trump has taken his attacks on her to a new level, she tried to push forward a more uplifting message, saying she wants to give people something to vote for, not just someone to vote against. Clinton’s speech at The Ohio State University was attended by the biggest crowd of the entire campaign. There, she presented the elections as a moral choice: “It may be who he is. But this election is our chance to show who we are”, Clinton said. “We are better than that. We are bigger than that. And I want to send a message to every boy and girl, every man and woman in our country, indeed the entire world, that that is not who America is.”2

1. Theoretical framework

This article aims to explain the relationship between discourse and social practices, so it is framed within the scope of Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA). CDA studies the relation between language, power and ideology (Fairclough 1995; Van Dijk 2001; Wodak 2002) and it integrates analysis of text, analysis of the processes of text production, consumption and distribution and sociocultural analysis of the discursive event (Fairclough 1995: 23). In order to account for the relationship between social practices and discourse, we closely investigate the linguistic choices employed in the message by the speakers in order to legitimise their arguments and delegitimise those of their opponent.

First, we employ lexical-semantic analysis to abstract the topics that both politicians talk about. Then we apply Benoit et al.’s (2003) functional theory of political campaign discourse3 to see how the two candidates acclaim themselves, attack the opponent and defend themselves when talking about each topic separately. Finally, we used Reyes’s (2011) strategies of legitimisation and investigated which ones the two speakers used when trying to acclaim themselves and legitimise their positions and which ones they used to attack their opponent and delegitimise their positions. In the second part of the analysis, we take a closer look at the pragmatic strategies Trump and Hillary employ to strengthen their arguments and establish closer contact with their voters.

Thus, according to Benoit et al.’s (2003) functional theory of political campaign discourse “candidates establish preferability through acclaiming themselves, attacking the opponent and defending themselves”. They manipulate the language and in this way try to impact the people into accepting their standing points and vote for them. Or, more precisely, by using different strategies to legitimise themselves and delegitimise their opponent they create so-called binary conceptualisations, us versus them (Van Dijk 1997), with us always being presented in a positive manner and them, of course, in a negative.

As for the (de)legitimisation strategies, as we previously mentioned, our analysis relies heavily on Reyes’s (2011) five categories of legitimisation, which are based mostly on the categories initially proposed by Van Leeuwen (2007). Although for Reyes, legitimising one position automatically implies the (de)legitimising of alternative positions, we apply them to the reverse process of delegitimisation as well (when speakers are criticising and attacking their opponent openly), while correlating them with the specific linguistic means employed. He suggests the following categories: 1. legitimisation through emotions, 2. legitimisation through a hypothetical future, 3. legitimisation through rationality, 4. voices of expertise, and 5. altruism.

Legitimisation through emotions: the appeal to emotions allows speakers to impose their opinion on the audience regarding a specific matter. They usually attribute negative qualities to their opponent’s personality, negatively presenting them, thus the speaker and audience are in the ‘us-group’ and the social actors depicted negatively constitute the ‘them-group’ (Reyes 2011: 785). Legitimisation is displayed through emotions, particularly fear, and social actors refer to what ‘the other’ is or does (Reyes 2011: 786).

Legitimisation through a hypothetical future is enacted when speakers, in order to exert their power, address the future by employing specific linguistic choices and structures, such as conditional sentences (Reyes 2011: 786). They will have positive expectations about the future that they intend to create, and negative about the future that their opponents would create.

The legitimisation through rationality is enacted when ‘political actors present the legitimisation process as a process where decisions have been made after a heeded, evaluated and thoughtful procedure’ (Reyes 2011: 786). It would be considered ‘rational’ if other sources are consulted and all the options are explored before making a decision. So, Reyes (2011: 786) suggests that these arguments would include verbs denoting mental and verbal processes such as ‘explore’ and ‘consult’.

Voices of expertise are displayed in discourse by speakers when they intend to show their audience that their arguments are supported by experts who also think the same. This legitimisation refers to the ‘authorization’ (Van Leeuwen 2007) that a speaker brings to the immediate context of the current speech to strengthen his/her position (Reyes 2011: 786).

Altruism is displayed by speakers when they want to present themselves as people who care, who serve others and do things for the common good, for the community and the people and are not guided by their own personal interests (Reyes 2011: 787).

Thus, before the analysis, we set our first hypothesis: our expectations were that both politicians would use lexical-semantic strategies to present themselves in a positive, and their opponent in a negative manner. Furthermore, we expected that candidates would differ in the choice of the strategies of legitimisation and delegitimisation, because of the different ideological positioning, personal experience, personality features, etc.

The second part of the analysis focuses on the investigation of the pragmatic strategies that these politicians used to present their arguments in the best possible manner and to attack and delegitimise their opponent. Our second hypothesis concerning this analysis was that: both politicians will make use of pragmatic strategies to best acclaim themselves and to attack their opponent, but there is going to be a difference in the pragmatic strategies both politicians employ to achieve these goals again based on the same reasons we mentioned before.

2. Analysis and discussion of findings

In the following section, we provide a thorough lexico-semantic and pragmatic analysis of the two selected speeches in order to investigate the strategies of legitimization and delegitimisation employed by both speakers in their attempt to win the 2016 American presidential election.

2.1 Legitimisation and delegitimisation strategies: lexical-semantic analysis

In the first part of the research, we analysed the topics that both politicians address (in Part A, we focus on topics Trump touches upon and in Part B on Hillary’s) and the positive or negative terminology they use to make a clear distinction between “us” and “them”. In addition, we analysed the strategies of legitimisation / delegitimisation they applied to acclaim themselves and attack their opponent. Finally, (in Part C) we investigated the strategies they employed to defend themselves.

A) Trump touches upon several themes in his speech, all aiming to help him acclaim himself and attack Hillary. He talked about:

a) the ability to fix problems: Legitimisation / delegitimisation through rationality

He stated that Clinton is the one who creates problems, but he fixes them (see examples (1) and (1a)). Thus, in (1), Trump states that he is aware of the existing problems and offers himself as a rational solution to the problems, thus legitimising himself through rationality. Consequently, he states that Hillary cannot solve these problems because she herself, as well as the party she represents created them.

Acclaims himself:

(1) When I see the crumbling roads and bridges, or the dilapidated airports, or the factories moving overseas to Mexico, or to other countries, I know these problems can all be fixed, but not by Hillary Clinton – only by me.

Attacks Hillary:

(1a) But we can’t solve any of these problems by relying on the politicians who created them. We will never be able to fix a rigged system by counting on the same people who rigged it in the first place.

honesty: Legitimisation through emotions and rationality and delegitimisation through emotions, rationality and voices of expertise.

In (2) Trump tries to convince the voters that he is the right candidate. He is an honest, a successful businessman and rationally he is the right choice for a president. At the same time, by stating that he is the one the country ‘desperately needs’ he creates a feeling of ‘despair’ thus appealing to people’s emotions of fear and need for change – and of course, he would bring that change. Fear is often developed in political discourse by a process of demonization of the enemy, and that process is linguistically realized by attributes (such as negative moral attitudes) and actions (Reyes 2011: 790). On the other hand, he tries to delegitimise Clinton (see examples (2a) – (2d)) by presenting her as corrupted, a liar and a thief, thus again appealing to audience’s emotions, and creating an atmosphere of fear – “If she is elected she is going to lie to you and steal from you”. To support his claims he introduces voices of expertise, as in (2a) and (2d). In (2a) he puts them all in the group of experts “you know that she is a liar”, thus appealing to their reason, and in (2d) he introduces a victim’s mother as a witness who had a first-hand experience with her and knows she is a liar, therefore, she must not be elected president of the country.

Acclaim himself:

(2) Yesterday, she even tried to attack me and my many businesses. But here is the bottom line: [...]. I have always had a talent for building businesses and, importantly, creating jobs. That is a talent our country desperately needs.

Attacks Hillary:

(2a) Hillary Clinton who, as most people know, is a world-class liar –just look at her [...], a total self-serving lie.

(2b) Hillary Clinton has perfected the politics of personal profit and theft. She ran the State Department like her own personal hedge fund – doing favors for oppressive regimes, and many others, in exchange for cash.

(2c) Hillary Clinton may be the most corrupt person ever to seek the presidency.

(2d) To cover her tracks, Hillary lied about a video being the cause of his death. Here is what one of the victim’s mothers had to say: “I want the whole world to know it: she lied to my face, and you don’t want this person to be president.”

being fair: Legitimisation through a hypothetical future and delegitimisation through emotions and rationality.

In examples (3) and (3a) Trump talks about fairness – he is fair but Clinton is not. He tries to legitimise his arguments through a timeline. In political discourse, the legitimisation process projects the future according to the possible actions taken in the present (Reyes 2011: 793). It has been a long period of unfairness, so if he is elected president he will put an end to it. He attacks Hillary by presenting her and her party as unfair, thus appealing both to people’s reason and emotions. Since no one wants to be ripped off and treated unfairly, no one should vote for her.

Acclaims himself:

(3) I am running for President to end the unfairness and to put you, the American worker, first. Here is my promise to the American voter: If I am elected President, I will end the special interest monopoly in Washington, D.C.

Attacks Hillary:

(3a) The other candidate in this race has spent her entire life making money for special interests – and taking money from special interests.

natural gifts and care for the American people: Legitimisation through altruism, delegitimisation through voices of expertise.

Another character aspect that Trump touches upon and tries to distinguish himself from Clinton is the natural gift for leading and love and care for the nation. He legitimises himself through altruism. He runs for president, not because of any selfish desire to gain power but simply, because he wants to make America great again. On the other hand, using Bernie Sanders as a voice of expertise, he delegitimises Clinton as egocentric, with no temperament and judgment to lead.

Acclaims himself:

(4) I know it’s all about you – I know it’s all about making America Great Again for All Americans. Our country lost its way when we stopped putting the American people first.

Attacks Hillary:

(4a) Hillary Clinton wants to be President. But she doesn’t have the temperament, or, as Bernie Sanders’ said, the judgment, to be president. She believes she is entitled to the office. Her campaign slogan is “I’m with her.” You know what my response to that is? I’m with you: the American people. She thinks it’s all about her.

leading abilities and foreign policy: Legitimisation and Delegitimisation through emotion.

In examples (5) – (5a) Trump touches upon the topic of foreign policy. In (5) he appeals to emotions of fear, triggering the images of “prison” and “death” in audience’s minds by saying that Clinton enslaves women and puts gay people to death, and continues in the same manner in (5a) with creating threatening images of death, destruction and terrorism which are all a result of her “leadership”. On the other hand, he presents himself as a reasonable person who has values and love and is going to protect the people from all that destruction.

Acclaims himself:

(5) I only want to admit people who share our values and love our people. Hillary Clinton wants to bring in people who believe women should be enslaved and gays put to death.

Attacks Hillary:

(5a) The Hillary Clinton foreign policy has cost America thousands of lives and trillions of dollars – and unleashed ISIS across the world. No Secretary of State has been more wrong, more often, and in more places than Hillary Clinton. Her decisions spread death, destruction and terrorism everywhere she touched.

B) Hillary Clinton also talks about five different topics and uses positive terminology to acclaim herself and negative to attack Trump. Thus, she also makes a clear distinction of “us” versus “them”, “us” being always good and right, while “them” being the bad option. She talks about:

moving the country forward: Legitimisation through rationality and altruism and delegitimisation through voices of expertise and emotions.

Clinton uses similar strategies to legitimise herself and her arguments that she is a better option than Trump. In (6), she legitimises herself through rationality and in (6) and (6a) through altruism. First, she mentions Trump’s low performance in the TV debate which should lead the voters to rationally elect her as a leader, thus, appealing to the audience’s reasoning and rationality. In addition, she supports her arguments with altruism, stating that her motive to be president is not egotistical but she must pull the country forward. She also involves the audience into the discourse with the use of inclusive “we” – “we’re going to move into the future together, creating what we need for ourselves and our children”. So, Trump moves the country backwards, but she will move it forward. In the next examples, she continues to delegitimise Trump’s candidacy. In (6b) through voices of expertise, she uses Michelle Obama, as an expert with whose statement she can back up her arguments that Trump is just not good enough to be president of the nation. In addition, she appeals to the audience’s emotions by creating terrifying images of Trump’s supposed leadership: dark and divisive future for the US (see 6(c)).

Acclaims herself:

(6) Any of you see that debate last night? [...]It was such a clear display of what’s at stake in this election. [...] I truly believe we are stronger together. To move our country forward.

(6a) I want to be a president for all Americans. And I am honored to have support, not just from Democrats, but from independents and Republicans, because we’ve got to pull this country together if we’re going to move into the future together, creating what we need for ourselves and our children.

Attacks Trump:

(6b) Now, the one thing I thought about last night and said was, as I was standing there on the stage with my opponent, was to remember what Michelle Obama had said. To paraphrase her, one of us went low and one of us went high.

(6c) America’s best days are ahead of us, not the dark and divisive vision of my opponent.

Fair treatment of people: Legitimisation and delegitimisation through rationality and emotions.

In (7) and (7a) Clinton addresses the ‘fair treatment’ issue and she skillfully involves the audience into her arguments by using inclusive “we” and appealing to their rationality – we treat everybody fairly and equally, we are bigger and better than Trump and his unfair policies. He is an insulter (see (7b)), he disrespects women, African-American, Latinos, Muslims, people with disabilities. He creates feelings of fear and threat, while she creates feelings of acceptance and trust.

Acclaims herself:

(7) That is not what we are in America. And it may be who he is, but this election is our chance to show who we are. We are better than that. We are bigger than that.

(7a) So we’re going to have more transparency so people have more incentive to make sure that everybody is treated fairly.

Attacks Trump:

(7b) We all heard on that tape what he thinks of women and how he treats women. [...] Yes, he’s insulted and demeaned women. But he has targeted others as well. He’s disrespected and denigrated African Americans and Latinos, Muslims and POWs, people with disabilities and immigrants. He is an equal-opportunity insulter.

decisions, plans for the future: Legitimisation and delegitimisation through rationality and hypothetical future.

In (8) and (8a) Clinton addresses future plans for the country. By appealing to the audience’s rationality in (8) she urges them to think and choose the right option. She also uses a conditional clause to create a hypothetical future: if you are on our side there will be a place for you in this nation of ours. She delegitimises Trump by mocking his plans for the future of America. She describes a future with him which sounds scary and unappealing. He will reverse marriage equality (will be against gay marriages), he will not let women decide about their health care (will prevent abortion), etc.

Acclaims herself:

(8) You know what’s at stake, but you also know what you believe. You know better than that. [...] You are helping us move toward a more perfect union. That has been the story of America at our best. We keep widening the circle of opportunity and inviting more people in. If you’re willing to do your part, you’re willing to make your contribution, there is a place for you in this nation of ours.

Attacks Trump:

(8a) And you don’t want someone who says that he’s going to appoint Supreme Court justices who will reverse marriage equality; who will – who will keep Citizens United, one of the worst decisions ever made, that allowed dark, unaccountable money in our electoral system; that will reverse a woman’s right to make her own health care decisions; who will defund Planned Parenthood.

i) climate change: Legitimisation through hypothetical future and delegitimisation through rationality.

Clinton also addresses the issue of climate change. She legitimises herself through a hypothetical future. However, she presents the future with the present tense, “when I am president...” to strengthen the audience’s belief that she is the one who is going to be elected. In addition, in (9a) she contrasts herself to her opponent. She delegitimises him by appealing to voters’ rationality – “he is not even interested in solving the problem, so apparently, you cannot expect anything from such a candidate”.

Acclaims herself:

(9) We have innovated. We have made the technology that could bring us into the forefront of this. And we’re going to do it. When I am president, I want all of you who care about science, technology, engineering, mathematics, I want you to be part of it.

Attacks Trump:

(9a) I’m running against somebody who doesn’t believe in climate change or at least he says he doesn’t , who has even said he thinks it’s a hoax created by the Chinese.

paying taxes: Legitimisation through hypothetical future and delegitimisation through rationality.

Finally, Clinton talks about taxes. She uses the same strategies as in the previous examples. First, in (10) she legitimises her arguments through a hypothetical future. She makes promises about a future where taxes will not be raised on the middle class, people striving to survive. In (10a) she delegitimises Trump by stating that he does not pay taxes although he is rich, thus appealing to voters’ reasoning that he is rich and successful because he does not give a dime to the state.

Acclaims herself:

(10) I will not raise taxes on the middle class. Nobody who is working hard to get ahead should be asked to pay more in taxes when we have so many people who have done so well and are not paying their fair share.

Attacks Trump:

(10a) Last night he finally admitted he hasn’t paid a dime in federal income tax for years. Now, he claims that’s because back in the early 1990s, he apparently lost a billion dollars running casinos. Who loses money running casinos? Really.

C) Both candidates employ strategies to defend themselves. Trump, for instance, defends his nomination, as in (11). He legitimises himself through altruism. He states that he is rich enough and does not run for president because of money or power but solely for altruistic reasons. He just wants to give back to the country what it has given to him.

(11) People have asked me why I am running for President. I have built an amazing business that I love [...]. So when people ask me why I am running, I quickly answer: I am running to give back to this country which has been so good to me.

In (12), he again defends himself from Clinton’s attacks, mostly legitimising himself through altruism (he simply wants to help the country which is in despair) and appealing to people’s emotions – the country is desperate and I can help it – my talent is what “our country desperately needs“

(12) Yesterday, she even tried to attack me and my many businesses. But here is the bottom line: I started off in Brooklyn New York, not so long ago, with a small loan and built a business worth over 10 billion dollars. I have always had a talent for building businesses and, importantly, creating jobs. That is a talent our country desperately needs.

In (13) Hillary defends her previous work as a Secretary of State, which Trump attacks. She appeals to people’s reasoning again trying to prove that she worked so hard for the country, while he was discriminating people (he was even sued for that), and was taking loans for starting businesses. She did all these good things for the country out of altruism, while he was only being nasty and egotistical. So, again, she uses rationality and altruism to legitimise herself and delegitimise her opponent.

(13) So when Donald Trump talks about what I’ve been doing for the last 30 years, I welcome that. I welcome it because in the 1970s, I was working to end discrimination and he was being sued by the Justice Department for racial discrimination against people in his apartments. And in the 1980s, I was working to improve the schools in Arkansas to make sure that teachers were well paid and that the coursework was going to prepare kids for the future, while he was getting a loan for $14 million from his father to start a business. And in the 1990s, I went to the UN Conference on Women and said women’s rights are human rights – while he was insulting Miss Universe, Alicia Machado. And on the day – on the day that I was in the Situation Room watching the raid that brought Osama bin Laden to justice, he was hosting Celebrity Apprentice. So if he wants to talk about what we have been doing the last 30 years, bring it on.

This part of the analysis confirmed our first hypothesis, that both politicians used lexical-semantic strategies to present themselves in a positive, and their opponent in a negative manner, thus making a clear distinction between “us” as the best option at the elections and “them” as a bad option or no option at all. As for their choice of strategies of legitimisation and delegitimisation, although they employed all of them to acclaim themselves and attack their opponent, there was some difference in their use by the two candidates, which makes this part of our hypothesis partially right. Trump mostly opted for appeals to emotions and rationality to acclaim himself and attack Hillary. He also used voices of expertise to support his arguments when delegitimising her. Hillary, on the other hand, tried to acclaim herself mostly by appealing to rationality and talking about hypothetical future in which she is the president and everything goes right for the country and delegitimised Trump mostly by appealing to audience’s rationality. This shows that Trump mostly focused on creating a feeling of fear so the audience can understand what suffering they would endure if Hillary is elected president; while for Hillary, it was reasonable to think that Trump is not the right person for the role he intends to play so she mostly aims at making people agree with that reasoning. This finding goes in line with Liu and Lei’s (2018) study, which revealed that Trump’s speeches were significantly more negative than Clinton’s.

She also used legitimisation through rationality to defend herself, while Trump defended his position relying on altruism, love for the country, provoked by the threat he sees if Hillary is elected president.

2.2 Legitimisation and delegitimisation strategies: Pragmatic analysis

In this part of our analysis, we focus more closely on the investigation of the pragmatic strategies employed by Trump and Hillary in their talks. More specifically, we focus on their use of metadiscourse4 to talk about their text (spoken text) and to give instructions to the audience on how they should understand and interpret their arguments. Appropriate use of metadiscourse markers adds to the building of the ethos, pathos and logos (Aristotle) as essential modes of persuasion. For the purposes of this analysis, we investigated the use of a few categories of interpersonal metadiscourse markers: hedges, intensifiers, self-mentions and engagement markers (see Hyland 2005). The use of these markers mostly helps the speakers to build an efficient ethos and present themselves as competent, authoritative, reliable and honest people, as well as pathos by involving the audience into the discourse and directly influencing their judgement (Hyland 2005: 75–85).

2.2.1 Interpersonal metadiscourse: the use of hedges and intensifiers

The use of hedges and intensifiers is an important strategy employed by speakers to express their commitment and assurance in the truth value of their arguments. Hedges, are employed by speakers as a technique of using tentative language to avoid full commitment to their arguments whenever they do not have strong arguments to support them, by mitigating their strength and present them as opinions rather than facts; while intensifiers, are employed by speakers to strengthen the propositions’ illocutionary force, and make strong, confident claims by showing conviction and degree of commitment in the truth value of their claims (Hyland 1998; 2005).

As can be seen from Table 1 below, Trump uses much more intensifiers than Clinton, who, on the other hand, uses hedges more often. This is a really interesting finding because it shows that obviously he is much more confident or wants to show that he is confident in what he states as a fact. And probably that really worked as a strategy. This finding, however, is not really in line with Savoy’s (2018) finding that in the oral form, Trump frequently uses verb phrases (verbs and adverbs) and pronouns, while Clinton is more descriptive (more nouns and prepositions). It seems that Clinton prefers the usage of verbs and adverbs too, but mostly. However, this might be a deliberative strategy used, as Holmes (1990) states: “women use I think in its deliberative, weight-adding function more often than men do”.

Table 1. Distribution of hedges and intensifiers in the corpora

|

TRUMP |

CLINTON |

||||

|

Most frequently used |

distribution / |

Most frequently used |

distribution / |

||

|

HEDGES |

Verbs (modal and lexical) |

modal: may, could, would |

3.0 |

modal: may, should, could, would lexical: think, guess |

5.6 |

|

Adverbs |

perhaps, maybe, probably |

1.5 |

maybe, probably |

0.6 |

|

|

INTENSIFIERS |

Verbs (modal and lexical) |

modal: will lexical: know |

6.6 |

modal: will lexical: know, believe, prove, emphatic do |

2.5 |

|

Adverbs |

absolutely, totally, so |

3.0 |

really, obviously, absolutely, truly |

3.8 |

|

|

Adjectives |

|

real, clear |

0.4 |

||

|

Nouns |

the fact |

0.6 |

the fact |

0.4 |

|

Trump made use of hedges to lower the strength of his statements mostly in cases when he strongly attacked Hillary, as in (1) and (2). For instance, in (1) he uses the modal verb may when making a strong accusation against Clinton stating that she is the most corrupt person ever, and in (2) he uses the adverb perhaps to mention one of the many terrifying things she has done.

(1) Hillary Clinton may be the most corrupt person ever to seek the presidency.

(2) Perhaps the most terrifying thing about Hillary Clinton’s foreign policy is that she refuses to acknowledge the threat posed by Radical Islam.

On the other hand, he uses intensifiers to acclaim himself as a reasonable and reliable candidate but also to attack Clinton. For instance, in (3) he uses the verb know to express his altruistic intentions that he is devoted to Americans and to making America great again. In (4), the use of epistemic will, helps Trump make negative predictions and legitimise his arguments through a hypothetical future. In contrast, he uses the adverb absolutely in (5) to strengthen his arguments against Hillary and delegitimise her through a hypothetical future in which she is presented as a person who could not be trusted. If she is given the opportunity, she will absolutely use it to do harm to the American people.

(3) I know it’s all about you – I know it’s all about making America Great Again for All Americans.

(4) We will never be able to fix a rigged system by counting on the same people who rigged it in the first place.

(5) The government of Brunei also stands to be one of the biggest beneficiaries of Hillary’s Trans-Pacific Partnership, which she would absolutely approve if given the chance.

Clinton uses hedges mostly to acclaim herself and to legitimise her good intentions, as in (6), when she talks about providing new jobs, or to lower the effect of criticism for her opponent, as in (7). She uses I guess when she actually tries to make fun of him and present him as incapable.

(6) I think we want new jobs with rising incomes.

(7) Well, I guess you do have to be a genius to lose a billion dollars in a year.

Hillary uses intensifiers less rarely than Trump but most of the time to acclaim herself as in (8) and (9) and get the support of the people while at the same time presenting herself as an already elected president.

(8) I truly believe we are stronger together.

(9) Obviously, I hope you do, but I will be your president, and I will stand up for you…

So, the analysis of the usage of hedges and intensifiers in both speeches revealed that the two candidates opted for different markers when trying to acclaim themselves and attack their opponents. Trump seemed to be more confident in doing both.

2.2.2 Self-mentions and engagement markers

Finally, both politicians used self-mentions and engagement markers mostly with the aim of acclaiming themselves. Self-mentions are markers which reveal the level of speaker’s presence in the text measured through the frequency of use of the personal pronouns and possessive adjectives (I, me, mine, exclusive we/ our/ us5) (Hyland 2005: 53). Engagement markers, on the other hand, are used by speakers to involve the audience in the discourse with: pronouns (you, your, inclusive we/our/us6) and at the same time they ‘lead’ readers towards an appropriate interpretation of their intention, with questions (rhetorical) and directives (mainly imperatives) (Hyland 2005: 53). Thus, the use of both these markers helps the politicians to acclaim themselves, i.e. with the use of self-mentions they focus the audience’s attention on themselves and their good and significant deeds, while with the use of engagement markers they involve the audience into the discourse they produce, no matter if they use it to attack the opponent or acclaim themselves. By doing that they want to leave the impression that the audience agrees with them.

Savoy (2018) found that the pronoun I was the most over-used term in the oral corpus for both Trump and Clinton. However, in our (relatively limited) corpora, Clinton used personal reference more frequently than Trump.

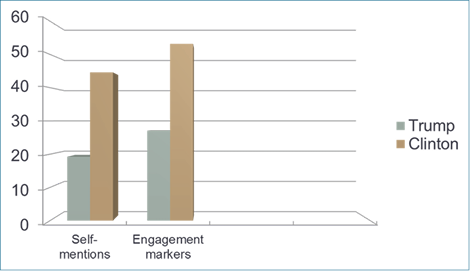

Fig. 1. Distribution of self-mentions and engagement markers in the corpora

As it can be seen from Graph 1 above, Clinton uses both self-mentions and engagement markers almost twice as frequently as Trump. Obviously, she uses different markers from him (Trump used intensifiers more) to achieve her goal. The only marker Trump uses more frequently is inclusive “our” – 15.3% vs. 7.7% per 1000 words. Jensen et al. (2016) in their research of Clinton’s campaign also found out that of all the pronouns she uses I and we most frequently. They state that “when Clinton says I, she takes all the responsibility on her shoulders, meaning that the communicative function is a statement that informs the recipients to trust her” (2016: 84). However, both politicians use a personal reference to acclaim themselves and attack their opponent.

In (1), for instance, Clinton uses I to openly attack and delegitimise Trump’s candidacy. She makes fun of his arguments presented at the debate and addresses the audience directly as if they already agree with her. Then with the use of the inclusive we, she involves them into the discourse and makes them equal contributors to the improvement of the country. In (2) she uses first and second person pronouns to persuade the audience to vote for her.

(1) Any of you see that debate last night? I’ll tell you what, I’m not sure you’ll ever see anything like that again. At least I hope you won’t. It was such a clear display of what’s at stake in this election. And I am thrilled to have the chance to talk with all of you about what we can do together because I truly believe we are stronger together. To move our country forward.

(2) And when you do, I want you to know what you’re voting for, because I don’t want you just to vote against something. I want you to vote for something. And here’s what we’re going to do.

Trump uses the first person pronoun mostly to legitimise his candidacy, as in (3), and to attack Hillary’s usage of self-reference, as in (4).

(3) I love what I do, and I am grateful beyond words to the nation that has allowed me to do it. So when people ask me why I am running, I quickly answer: I am running to give back to this country which has been so good to me.

(4) Her campaign slogan is “I’m with her.” You know what my response to that is? I’m with you: the American people. She thinks it’s all about her.

When they use exclusive “we” or “our” they usually refer to their political party (see examples (5)-(7)).

(5) That’s why we’re asking Bernie Sanders’ voters to join our movement: so together we can fix the system for ALL Americans. (Trump)

(6) We are going to end the cowboy culture on Wall Street and what happens in too many boardrooms. We’re going to defend the tough new rules on Wall Street that President Obama got passed, the Dodd-Frank rules. (Clinton)

(7) Because we want everybody to vote and we particularly want young people to vote because this is your election more than anybody else’s. (Clinton)

But they also use inclusive “we” or “our” as in (8), to involve the audience into the discourse and create the feeling of belonging to the same group, nation or political party.

(8) We’ve lost nearly one-third of our manufacturing jobs since these two Hillary-backed agreements were signed. Our trade deficit with China soared 40% during Hillary Clinton’s time as Secretary of State. (Trump)

All in all, the analysis showed that both politicians make use of personal reference and inclusive pronouns to better acclaim themselves and attack their opponent. However, there was a difference between the two candidates as Clinton uses this persuasive strategy much more frequently than Trump.

Conclusion

The main aim of this paper was to investigate the strategies politicians use to legitimise themselves and delegitimise their opponent. Being still under the influence of the last American elections, we conducted a Critical Discourse Analysis of two speeches from Trump and Clinton’s 2016 campaigns. First, following Benoit et al.’s (2003) functional theory of political campaign discourse, we carried out a detailed lexical-semantic and pragmatic analysis in order to extract the arguments in which candidates tried to establish preferability through acclaiming themselves, attacking the opponent and defending themselves. Then, we implemented Reyes’s categories of legitimisation on these examples and investigated which ones candidates used when they wanted to acclaim themselves and legitimise their arguments and which ones were used when they attacked the opponent and tried to delegitimise their positions. So, although Reyes (2011) stated that legitimising one position automatically implies (de)legitimising of alternative positions, we decided to apply his strategies to the reverse process of delegitimisation as well and see if there is a difference in the choice of strategies the two candidates made.

The analysis confirmed both our hypotheses true. Firstly, it was seen that both politicians used lexical-semantic discourse strategies to present themselves in the best possible manner and present their opponent as the complete opposite of what they represent. However, Trump mostly appealed to audience’s emotions provoking fear both when acclaiming himself and attacking Clinton, while she mostly appealed to audience’s rationality, since for her, it was rational that she was elected president as she was a better option than Trump. She also used legitimisation through rationality to defend herself, while Trump defended his position relying on altruism and love for the country.

In the second part of the analysis, we investigated the usage of interpersonal metadiscourse markers more deeply. The analysis revealed differences in the usage of these markers between Trump and Clinton. For instance, Trump used much more intensifiers than Clinton, who used more hedges, self-mentions and engagement markers. Whether the use of specific markers has influence on the overall persuasive effect of the speeches and consequently on the voting results, needs to be investigated further on a larger corpus. Finally, although carried out on a very small corpus, the analysis does shed some insight into the strategies politicians use to manipulate the public into voting for them and not for their opponent.

References

Benoit, W. L., Mchale, J. P., Hansen, G. J., Pier, P. M., Mcguire, J. P., 2003. Campaign 2000. A Functional Analysis of Presidential Campaign Discourse. Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Clinton 2016. Transcript of Hillary Clinton’s speech at Ohio State. 11/10/2016. The Columbus Dispatch. Available at: <http://www.dispatch.com/content/stories/local/2016/10/11/hillary-clintons-speech-at-ohio-state.html> [Accessed 15 November 2018].

Cap, P., 2008. Towards the proximization model of the analysis of legitimization in political discourse. Journal of Pragmatics, 40: pp.17–41. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2007.10.002> [Accessed 15 November 2018].

Crismore, A., Farnsworth, R., 1990. Metadiscourse in Popular and Professional Science Discourse. The Writing Scholar: Studies in the Language and Conventions of Academic Discourse. Newbury Park, CA: Sage, pp.45–68.

Crismore, A., Markannen, R., Steffensen, M., 1993. Metadiscourse in Persuasive Writing. A study of texts written by American and Finnish University students. Written Communication, 10(1), pp.39–71. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088393010001002> [Accessed 15 November 2018].

Darweesh, A. D., Abdullah, N. M., 2016. A Critical Discourse Analysis of Donald Trump’s Sexist Ideology. Journal of Education and Practice, 7(30), pp.87–95. Available at: <https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1118939.pdf> [Accessed 15 November 2018].

Fairclough, N., 1995. Critical Discourse Analysis: The Critical Study of Language. Pearson Education Limited.

Holmes, J., 1990. Hedges and boosters in women’s and men’s speech. Language & Communication,10(3), pp.185–205. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1016/0271-5309(90)90002-S> [Accessed 15 November 2018].

Hyland, K., 1998. Persuasion and context: The pragmatics of academic metadiscourse. Journal of Pragmatics, 30(4), pp.437–455. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-2166(98)00009-5

Hyland, K., 2005. Metadiscourse. Exploring Interaction in Writing. MPG Books Ltd, Bodmin, Cornwall.

Jensen, I., Jakobsen, I. K., Pichler, L. H., 2016. A Critical Discourse Study of Hillary Clinton’s 2015/2016 Presidential Campaign Discourses. Master Thesis (Online). Available at: <https://projekter.aau.dk/projekter/files/239472135/Master_s_Thesis.pdf> [Accessed 15 November 2018].

Liu, D., Lei, L., 2018. The appeal to political sentiment: An analysis of Donald Trump’s and Hillary Clinton’s speech themes and discourse strategies in the 2016 US presidential election. Discourse, Context & Media, 25, pp.143–152. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcm.2018.05.001> [Accessed 15 November 2018].

Reyes, A., 2011. Strategies of legitimization in political discourse: From words to actions. Discourse & Society, 22(6), pp.781–807. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926511419927 [Accessed 15 November 2018].

Rojo, M. L., Van Dijk, T. A., 1997. There was a problem, and it was solved! Legitimating the expulsion of ‘illegal’ immigrants in Spanish parliamentary discourse. Discourse & Society, 8(4), pp.523–567. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926597008004005> [Accessed 15 November 2018].

Savoy, J., 2018. Trump’s and Clinton’s Style and Rhetoric During the 2016 Presidential Election. Journal of Quantitative Linguistics, 25(2), pp.168–189. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1080/09296174.2017.1349358> [Accessed 15 November 2018].

Trump 2016. Full transcript: Donald Trump NYC speech on stakes of the election. 06/22/2016. POLITICO. Available at: <http://www.politico.com/story/2016/06/transcript-trump-speech-on-the-stakes-of-the-election-224654> [Accessed 15 November 2018].

Van Dijk, T. A., 1997. What is Political Discourse Analysis? In: Congress Political Linguistics. Eds. J. Blommaert, C. Bulcaen. Antwerp. In: Political Linguistics, pp.11–52. Available at: <http://discourses.org/OldArticles/What%20is%20Political%20Discourse%20Analysis.pdf> [Accessed 15 November 2018].

Van Dijk, T. A., 2001. Critical Discourse Analysis. In: Handbook of Discourse Analysis. Eds. D. Tannen, D. Schiffrin, H. Hamilton. Oxford: Blackwell, pp.352–371. Available at: <https://is.cuni.cz/studium/predmety/index.php?do=download&did=100284&kod=JMM654> [Accessed 15 November 2018].

Van Leeuwen, T., 2007. Legitimation in discourse and communication. Discourse & Communication, 1(1), pp.91–112. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1177/1750481307071986> [Accessed 15 November 2018].

Wodak, R. 2002. Aspects of Critical Discourse Analysis. Zeitschrift für Angewandte Linguistik, 36: pp.5–31. Available at: <http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.121.1792&rep=rep1&type=pdf> [Accessed 15 November 2018].

1 Read more about this here: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/23/us/politics/donald-trump-speech-highlights.html.

2 Read more about this here: https://www.npr.org/2016/10/11/497487314/clinton-uses-intense-presidential-debate-to-try-to-win-over-young-voters.

3 Explained later in this section.

4 According to Crismore and Farnsworth (1990), Crismore et al. (1993), Hyland (1998) metadiscourse can be textual and interpersonal. Textual metadiscourse organises the text and directs readers towards the intended interpretation. Interpersonal metadiscourse, on the other hand, helps writers to express their attitude towards the proposition and establish a certain relationship with the readers.

5 Exclude the audience (listeners).

6 Includes the audience (listeners).