Respectus Philologicus eISSN 2335-2388

2024, no. 45 (50), pp. 9–24 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15388/RESPECTUS.2024.45(50).1

A Taste of Metaphor Variation: Contrasting the Metaphorical Extensions of “stew” and “guisar”

Montserrat Esbrí-Blasco

Universitat Jaume I – Department of English Studies/IULMA

Sos Baynat s/n, 12006 Castelló de la Plana, Spain

Email: esbrim@uji.es

ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0429-0418

Research interests: Metaphor analysis, Contrastive linguistics, Frame semantics

Abstract. This article examines the range of metaphors activated by the cooking term stew in English and its Spanish counterpart guisar. The data were drawn from Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA) and Corpus del Español: Web and Dialects. The metaphors were identified by applying MIP (Pragglejaz Group, 2007) and incorporating semantic frames (Fillmore, 1982) to provide a detailed analysis of the mappings between the core frame elements involved, and the thematic roles performed by those elements. The results suggest that English and Spanish diverge considerably regarding the metaphors evoked by stew and guisar. The lemma stew activated a broader scope of metaphorical extensions than guisar. Just one shared metaphor was identified, which underscores the presence of distinct cognitive preferences within the respective languages.

Keywords: contrastive semantics; conceptual metaphor; semantic frame; domain.

Submitted 14 September 2023 / Accepted 12 January 2024

Įteikta 2023 09 14 / Priimta 2024 01 12

Copyright © 2024 Montserrat Esbrí-Blasco. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License CC BY 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

Conceptual metaphors are cognitive mechanisms that hold profound significance in comprehending and representing abstract ideas (Kövecses, 2020; Lakoff, 1993; Lakoff, Johnson, 2003). By conceptually projecting concrete domains onto abstract or complex concepts, metaphors facilitate our interpretation of the world around us.

Metaphors are not only grounded on sensorimotor experience but also on the cultural environment. Therefore, as metaphors may vary across cultures (Gibbs, 1999; Ibarretxe-Antuñano, 2013; Kövecses, 2005), cross-linguistic studies of metaphor variation can provide valuable insights into the way diverse cultures reason about a given concept. Examining conceptual metaphors cross-linguistically may offer a window into the intricate interplay between language, mind and culture, thereby enriching our understanding of the diverse manners in which humans perceive and interact with the world.

In this line, this study conducts a cross-linguistic analysis of the metaphorical senses activated by stew in American English (AmE) and guisar in Peninsular Spanish (PenSp), comparing their metaphorical instances taken from Corpus del Español: Web/Dialects (Davies, 2016) (henceforth, CEWD) and COCA (Davies, 2008). This study can be framed within the realm of Cognitive Semantics and uses semantic frames as a tool for describing metaphorical mappings in detail.

Hence, the aim of this work is to delineate the scope of metaphorical frames evoked by stew and guisar in AmE and PenSp and contrast them in order to elucidate the cross-linguistic divergences among the metaphors evoked.

Learning about the cross-cultural variation of certain metaphors can facilitate effective communication across languages. Therefore, this study may have considerable implications not only for Cognitive Semantics and metaphor theory but also for language teaching, translation practices and intercultural communication.

1. Cultural divergence in metaphorical configurations

Culture shapes metaphorical configurations by selecting the aspects of human experience that are more salient in a given cultural context (Dobrovol’skij, Piirainen, 2022; Esbrí-Blasco, Navarro i Ferrando, 2023; Kövecses, 2020; Littlemore, 2019; Yu, 2012). Therefore, exploring the variation of metaphorical patterns of conceptualisation across languages can furnish invaluable elucidations regarding how distinct cultures conceptualise a specific concept.

Regarding cross-linguistic metaphor variation of the cooking domain, current research on culinary metaphors primarily centres on food rather than culinary actions, and when doing so, limited attention is given to investigating the specific mappings between the SF and TFs underlying the culinary metaphorical expressions.

Khajeh and Ho-Abdullah (2012) explored the metaphorical conceptualisations of sexual lust as food, temperament as food and thought/ideas as food in English and Persian. Their study reveals the prevalence of culinary and food-related metaphors in Persian, emphasising the direct connection between the meaning of those expressions and the Persian culture and society. They present instances of culinary metaphorical expressions in Persian and their corresponding English translations without exploring the internal configuration of the mappings.

Tsaknaki (2016) undertook a cross-linguistic study of culinary verbs in French and Greek that examined whether certain culinary actions share the same metaphorical senses in each language. While valuable in revealing certain cross-linguistic variations, all the conceptual metaphors analysed were formulated with cooking as the source domain. Consequently, the study failed to identify the mappings at a less schematic conceptual level for each of the cooking verbs investigated.

Similarly, Zhai (2023) explored the polysemy of cooking verbs in Chinese and Spanish. She focused on a selection of target domains and listed the culinary actions associated with those senses. Zhai (2023) explained the general mappings and provided examples of metaphorical expressions evoking those mappings without providing a detailed examination of each particular cooking verb, which limits the depth of comprehension and the contrast of the conceptual metaphors selected and the nuances of those culinary verbs when activating the identified target domains.

Esbrí-Blasco and Navarro i Ferrando (2023) conducted a cross-linguistic study of the metaphorical senses activated by hornear and bake in Spanish and English. Utilising data from COCA and CEWD, they identified metaphorical instances integrating frame analysis into MIP to unveil the range of TFs evoked by those cooking verbs, along with the frame elements (FEs) and their corresponding thematic roles involved in the mappings. Their study uncovered the main similarities and divergencies in the metaphorical usage of these terms, additionally showing that both languages place experiential focus on distinct thematic roles and FEs when constructing mappings.

Building upon the methodology employed by Esbrí-Blasco and Navarro i Ferrando (2023), the present study extends this line of research to a distinct pair of culinary verbs, namely stew and guisar. The current analysis involves the identification of TFs, FEs, and the corresponding thematic roles and type of process implicated in these metaphorical mappings. This nuanced examination contributes to a deeper understanding of conceptual mappings in culinary metaphors, shedding light on the unique intricacies characterising the metaphoric usage of stew and guisar.

2. Methodology

This article follows a source-oriented approach (Stefanowitsch, 2006) to examine the TFs associated with stew and guisar. These cooking terms are considered translation equivalents as their basic sense is the same in English and Spanish dictionaries. The most frequent collocations of stew and guisar were retrieved from COCA and CEWD, respectively, and that contextual evidence, together with the non-metaphorical uses extracted from the corpora, allowed for building the shared SF stewing/guisar.

The decision to analyse 3,000 random instances of stew in AmE and 2,059 instances of guisar in PenSp was influenced by several factors. As posited by Deignan (2005, p.40), a metaphorical sense manifesting less than once per 1,000 corpus citations may be considered as rare. Thus, this study aimed to ensure a sufficiently large sample size to capture a diverse range of metaphorical expressions. The initial intention was to analyse 3,000 instances in each language, but our sample size was adjusted since CEWD only contained 2,059 instances of guisar. Normalising the occurrence counts of stew and guisar in terms of frequency per million words (i.e., stew 6.06 and guisar 4.48) shows that, although not all citations of stew were analysed, the prevalence in language use of stew in AmE remains more significant than guisar in PenSp. Furthermore, to facilitate a meaningful comparison, the relative frequency of the total number of instances analysed was calculated, along with the relative frequency of the total number of metaphorical expressions identified in each language (see Table 1).

As for metaphor identification, MIP (Pragglejaz, 2007) identifies metaphor at the linguistic level, determining whether a word is being used metaphorically. MIP does not address the conceptual dimension, as it does not identify the source and target configurations involved in a metaphor. To overcome this limitation, this study adopts a refined version of MIP (see Esbrí-Blasco, Navarro i Ferrando, 2023), integrating frames as a semantic tool for identifying the SF and TFs as well as the specific FEs engaged in the metaphorical mappings. Unlike MIP, this version not only identifies metaphorical expressions but also explores mappings at the conceptual level. The decision regarding whether a term is metaphorical transcends the contextual-basic meaning comparison, also comparing the TFs these senses activate. Thus, this approach goes beyond mere metaphor detection by identifying FE’s mappings.

Section 3 illustrates this refinement of MIP by analysing corpus instances of stew and guisar. The analysis not only determines the instances that could be tagged as metaphorical but also examines the TFs evoked and the mappings. For instance, it reveals how stew may metaphorically evoke frames such as musing on a subject and mental agitation, among others.

For determining the literal and contextual meaning of PenSp, we relied on the normative dictionary approved by the Spanish Royal Academy of the Spanish Language (i.e., Diccionario de la Real Academia Española). Due to the absence of a normative dictionary in English and to ensure a comprehensive understanding of the contextual senses of the English occurrences, in each occurrence, we consulted three widely recognised dictionaries: Cambridge Dictionary Online, Merriam Webster’s Online Dictionary, and MacMillan Dictionary. Each of these dictionaries brings its own lexical coverage, contributing to a more thorough exploration of the terms under investigation.

After a general understanding of the instances within the corpora, the contextual meaning of stew/guisar was determined for each occurrence. Following, if the frame activated by stew/guisar in a given citation deviated from the literal stewing/guisar frame in their basic dictionary definitions and instead evoked a frame bearing a certain resemblance between its FEs and the stew/guisar FEs, that instance was categorised as metaphorical. Upon identification, the TFs activated by stew and guisar were characterised, and the FEs participating in the conceptual projections, along with their respective thematic roles.

3. Results

3.1 STEWING and GUISAR as SFs

The lexical items stew and guisar evoke a prototypical frame within the cooking domain consisting of a number of FEs and their corresponding thematic roles described in Figure 3. This particular frame refers to the process of stewing, whose Aktionsart can be interpreted as a causative active accomplishment (Van Valin, LaPolla, 1997). Therefore, the stewing/guisar SF entails a process in which an intentional agent provokes the change of state of an entity. More specifically, a cook [agent] places tiny food portions [patient] (commonly meat and vegetables) into a stewing container [location] and submerges all the ingredients in liquid [means] for an extended period of time over low heat [effector].

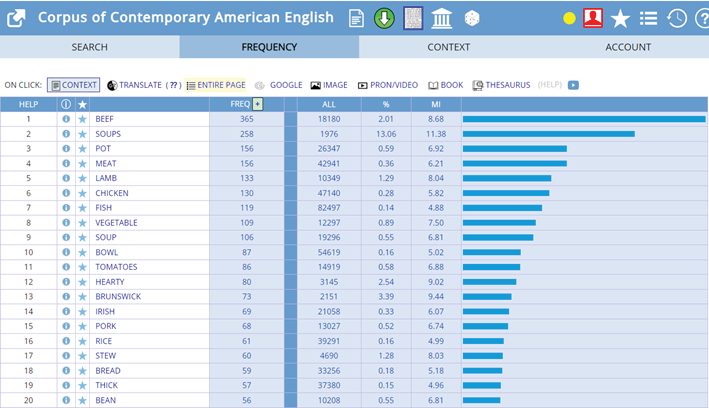

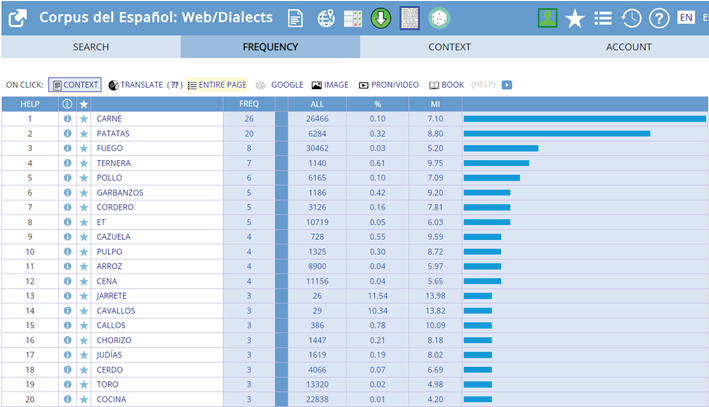

As for the SF, the most common collocates of stew and guisar in COCA and CEWD corroborate that their literal use is primarily associated with cooking food in AmE and PenSp, as depicted in Fig. 1 and 2.

Fig. 1. Stew collocates in COCA

Fig. 2. Guisar collocates in CEWD

The examination of literal occurrences of stew and guisar in COCA and CEWD, as well as their most frequent collocations, facilitates the construction of the SF activated by stew and guisar as one frame shared by both terms in AmE and PenSp, as illustrated in Fig.3.

|

STEWING - GUISAR FRAME |

|

Description: cooking small and uniform pieces of food totally submerged in liquid for an extended period at a low temperature. |

|

CORE FEs |

|

▪ Cook: person cooking the food [agent] |

|

▪ Pre-cooked food: tiny portions of food before the stewing process [patient] |

|

▪ Heating device: equipment -cooking stove- generating heat to cook food [instrument] |

|

▪ Stewing container: cooking vessel placed on the stove containing the pieces of food and liquid [location] |

|

▪ Liquid: liquid utilized for stewing, normally wine or stock [means] |

|

▪ (Low) Heat: heat generated by the stove stewing the ingredients [effector] |

|

▪ Chemical reactions: transformations undergone by the ingredients during the stewing process (accomplishment) |

|

▪ Culinary outcome: tender portions of food in dense sauce [result] (resulting state) |

Fig. 3. stewing – guisar as an SF.

As for the lemma stew, 3,000 random occurrences searched in COCA were analysed to determine whether stew was being used metaphorically. With respect to guisar, all the available instances (i.e., 2,059) in CEWD were considered. The lexical item stew was used metaphorically in 441 (14.7%) instances, whereas guisar was tagged as metaphorical in 204 (9.91%) instances. The following sections examine the metaphorical senses identified in each language.

3.2 English TFs

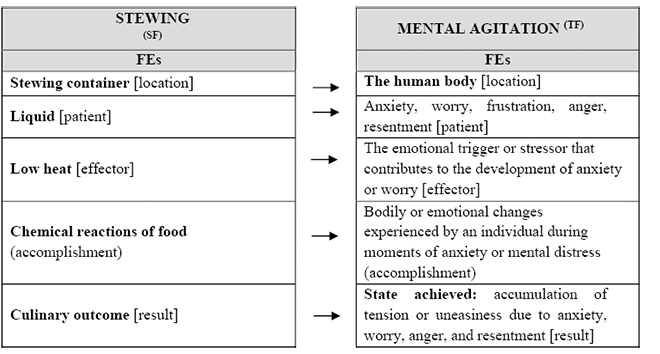

3.2.1 TF1: mental agitation

In COCA, 65 examples (2.17%) of the mental agitation TF were identified. This frame represents a prototypical situation in which an individual experiences repressed mental agitation, nervousness or concern. Figure 4 portrays the conceptual correspondences between the stewing SF and the mental agitation TF.

Figure 4 shows that the human body containing negative emotions is understood as a vessel containing liquid and food. Moreover, the cause triggering the unpleasing emotion is envisioned as the low heat warming up the food portions and the liquid. In turn, the emotional and/or physical changes the body undergoes while facing the unpleasant situation correlate with the liquid and the pieces of food going through chemical reactions. The state achieved (i.e., anxiety, concern or frustration) is deemed axiologically negative in mental agitation (TF), in contrast to stewing (SF). Examples (1) and (2) illustrate these mappings:

MENTAL AGITATION IS STEWING*

Fig. 4. TF 1: mental agitation

* The mappings are designated according to the CMT, conventional pattern target is source

(1) “Charles moves away, still very upset. # Joseph loves how angry Charles is, finds it funny to watch him stew”. (COCA, FIC: American Theatre, 2012).

(2) “I was overcome with anger and frustration. Where was the damn electricity? I asked nobody in particular. As I stewed in my anger, the kerosene in my lantern ran out and a thick soot of darkness fell upon me”. (COCA, FIC: Literary Review t, 2009).

(3) “They just read Noah Thacken’s will, and the family’s in a stew. He left the house to daughter number two, so daughter number one is threatening to sue, and daughter number three is threatening to leave town”. (COCA, FIC: Lake news : a novel, 2000).

In example (1), Charles’ body is viewed as a stewing container of anger and frustration. Similarly, example (2) illustrates that the verb stew tends to collocate with the preposition “in” followed by the negative emotion (e.g. stew + in + anger/frustration/outrage/envy). Interestingly, as shown in example (3), the TF mental agitation can also be linguistically realised by the prepositional phrase “in a stew”, which entails that people being agitated may be viewed as immersed in a stew of negative emotions.

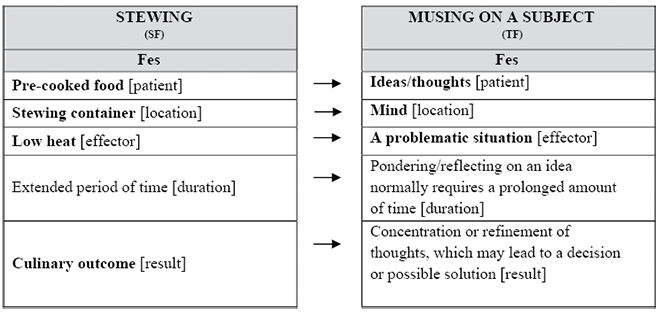

3.2.2 TF2: musing on a subject

The musing on a subject frame was activated in 155 (5.17%) out of the 3,000 occurrences of stew. This frame involves an individual affected by a complex or problematic situation who mulls over it carefully.

As represented in Figure 5, the person’s mind and corresponding thoughts or ideas can be conceptualised as the pieces of food slowly stewed in the cooking container. The complex situation that triggers the reflective thoughts is viewed as the low heat that stews the pieces of food for a prolonged duration. Examples (4) and (5) display these mappings:

MUSING ON A SUBJECT IS STEWING

Fig. 5. TF2: musing on a subject

(4) “After long stewing over it, I finally realized who Donald Trump reminds me of, and it is scary”. (COCA, NEWS: Chicago Tribune, 2016).

(5) “I spent the day stewing over what to do.”. (COCA, FIC: Fantasy & Science Fiction, 2004).

Examples (4) and (5) clearly portray how stew refers to people mulling over a certain situation for an extended period as if their ideas were pieces of food stewing at a low temperature.

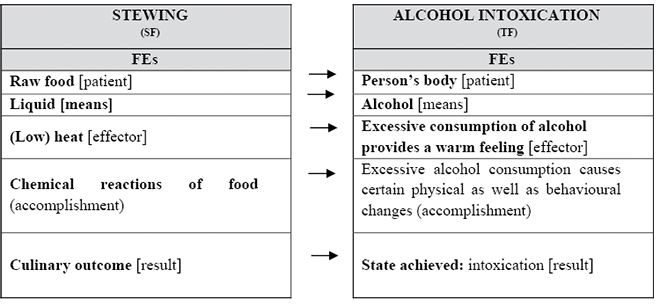

3.2.3 TF3: alcohol intoxication

The alcohol intoxication frame manifests in 12 (0.4%) occurrences of COCA. This frame configures a situation where an individual has consumed a significant amount of alcohol, leading to clear signs of intoxication.

As Figure 6 shows, a number of FEs from the stewing frame can be conceptually aligned with alcohol intoxication. The individual consuming a substantial volume of alcohol and suffering changes in bodily functions and behaviour could be conceptualised as food submerged in liquid during the process of stewing. Examples (6) and (7) portray these mappings:

(6) “The bottle is in front of Pete, who sits at the bar, quietly getting stewed”. (COCA, FIC: The Bijou, 2001).

(7) “So, these fellas are out fishing and they’re really having a time and drinking it up. They’re getting awful stewed”. (COCA, FIC: Stern men, 2000).

In examples (6) and (7), getting stewed refers to drinking too much alcohol and, as a consequence, getting intoxicated. The inebriated people can be conceived as the ingredients stewing in a significant amount of wine or stock.

ALCOHOL INTOXICATION IS STEWING

Fig. 6. TF3: alcohol intoxication

3.2.4 Schematic mapping: Integration is stewing

Stew activates stewing as a source of metaphorical conceptualisation mapping onto a schematic TF in 189 (6.33%) citations. stewing projects a number of FEs without focusing on a prototypical scenario within the TF. Therefore, stew aligns with a variety of TFs representing an integrated combination of distinct interacting elements.

The TFs share the following schematic configurational features: a) a number of component parts (abstract or physical), and b) the accomplishment of combining or integrating those component parts into a unified entity. The TFs comprising this configuration (a and b) may be associated with certain features of the frame stewing: a) the simultaneous stewing of multiple ingredients and b) the accomplishment of fusing liquid and solid ingredients into a unified entity (i.e., a stew). Examples (8) and (9) manifest this mapping:

(8) “The D.C.-based duo of Rob Garza and Eric Hilton have been mixing up an eclectic stew of danceable global grooves, reggae rhythms and intoxicating acid jazz for 15 years”. (COCA, NEWS: Austin American Statesman, 2012).

(9) “This patient, for instance, ingests a complex stew of medicines, 15 in all”. (COCA, MAG: Fortune, 2002).

In example (8), the music created by the musicians is conceptualised as an “eclectic stew” whose main ingredients (“danceable global grooves, reggae rhythms and intoxicating acid jazz”) have been “mixed up”. In example (9), the combination of medicines ingested by a patient is construed as a “complex stew”.

3.2.5 Idiom: to stew in one’s own juices

The informal AmE idiom to stew in one’s own juices refers to pondering over one’s negative feelings or suffering the consequences of your own actions in solitude, without the intervention of other people. This idiom seems to be an extension of stewing over, since it involves brooding over a problematic situation too, but, as the occurrences portray, this idiom is usually deployed to convey the meaning of being left alone reflecting and/or enduring the consequences of your actions, as though confronting those negative thoughts were being left immersed in the broth of a simmering stew. To stew in one’s own juices was identified in 20 (0.67%) occurrences of stew in COCA. Consider the following example:

(10) “I don’t want them helped! They made this mess. They shut me out of their lives. Let them stew in their own juices! They deserve whatever they get”. (COCA, FIC: Analog Science Fiction & Fact, 2001).

In example (10), the character complains about other people’s actions and wants them to stew in their own juices, that is, to face the consequences of their acts and not to receive anyone’s help.

3.3 Spanish TFs

3.3.1 Schematic mapping: elaboration is stewing/guisar

The current section explores the metaphors conveyed by guisar and its nominalisation guiso in 204 (9.91%) metaphorical instances out of the 2,059 occurrences extracted from CEWD. The metaphor elaboration is stewing/guisar is evoked in 11 (0.53%) guisar instances. The guisar/stewing frame can be mapped onto multiple TFs, implying a progression in shaping an entity until it reaches full elaboration. Thus, the potential TFs encompass these features: a) an initial, unrefined (abstract or physical) entity requiring development, and b) the accomplishment of complete development of the said entity. The TFs encompassing this schematic configuration (a and b) can be conceptually linked to diverse elements of stewing: a) raw ingredients and b) the accomplishment of converting the pre-cooked elements into a stew (see example (11) and (12)).

(11) “Conoceremos el final de la novela, que se está guisando a fuego lento en estos mismos momentos en Twitter, el próximo 6 de febrero”. (CEWD, http://nonperfect.com/tag/twitter/).

“We will know about the end of the novel, which is being slowly elaborated right now on Twitter, next February 6th”.

(12) “Qué ganas de un nuevo disco de U2. Puede ser un gran álbum lo que han estado guisando durante los últimos meses con Danger Mouse”. (CEWD, http://lostop10delahiguera.blogspot.com/2013/06/10-canciones-para-seguir-tu-camino.html).

“I’m looking forward to a new U2 album. What they’ve been elaborating for the last months with Danger Mouse can be a great album”.

Examples (11) and (12) depict how guisar is related to the complexity of elaborating an entity (a novel in example (11) and a music album in (12)), as though the resulting entity were a stew cooked slowly to reach its full flavour potential.

3.3.2 Schematic mapping: Integration is stewing/guisar

integration is stewing/guisar is a schematic mapping evoked in 21 (1.02%) out of the 2,059 guisar citations. Examples (13) and (14) illustrate several linguistic realisations of this conceptual projection in PenSp.

(13) “La campaña que se nos viene encima tendrá todos los ingredientes del mejor guiso desestabilizador de las conciencias”. (CEWD, http://corresponsalesdelpueblo.bligoo.com/martin-guedez-ante-el-8-d-la-confusion-reinante-y-la-avanzada-fascista-reformista-que-hacer).

“The campaign bearing down on us will have all the ingredients of the best stew for destabilising conscience”.

(14) “Pretender que en un mismo espacio convivan familias, gente joven, peñistas, jubilados, turistas extranjeros... en un evento festivo es, cuanto menos, arriesgado. Demasiado ingrediente heterogéneo para un guiso tan explosivo”. (CEWD, http://blogs.opinionmalaga.com/lavidamoderna-merma/2013/08/22/la-feria-indigna-de-ser-vivida/).

“Expecting that families, youngsters, ‘peñistas’, retirees, tourists…meet together in the same place in a festive event is risky, to say the least. There are too many heterogeneous ingredients in such an explosive stew”.

Example (13) implies the distinct components constituting a political campaign are conceptualised as the ingredients of a stew. Similarly, in example (14), the distinct types of people attending “La Feria de Málaga” are envisioned and linguistically characterised as an explosive stew consisting of diverse heterogeneous ingredients.

3.3.3. Idiom: Yo me lo guiso, yo me lo como

The metaphorical idiom yo me lo guiso, yo me lo como was identified in 172 (8.35%) citations in CEWD and may be used in PenSp to emphasise someone’s selfishness. However, it is usually utilised to positively point out someone’s self-sufficiency, evoking the taking on responsibility on one’s own affairs frame. In this regard, some people do not need external help in their businesses, as they are the ones “stewing” their own issues. Consequently, they are the ones benefiting from or facing the consequences or final results (someone has stewed it so that he/she is the one who eats it afterwards). As a case in point, consider example (15):

(15) “Yo sé que he aprendido a vivir lo que me da la vida y no a esperar que lo bueno dependa de otros, soy yo la protagonista de mi felicidad, yo me lo guiso y yo me lo como”. (CEWD, http://blogs.laverdad.es/marcleo/)

“I know I have learnt to live what life offers to me and not to wait for the good to depend on others, I am the protagonist of my happiness, I run the whole show”.

Example (15) shows that when someone addresses their personal challenges independently, it can be understood as a chef preparing their own meal and relishing the resulting dish (i.e., reaping the benefit of his/her own actions).

Table 1 provides the relative frequency of the metaphorical mappings examined in sections 3.2 and 3.3.

Table 1. Frequency of stewing and guisar TFs in AmE and PenSp.

|

Alternative TFs in AmE |

AF* |

T-RF* |

M-RF* |

|||

|

mental agitation |

65 |

2.17% |

14.74% |

|||

|

musing on a subject |

175 |

5.83% |

39.68% |

|||

|

alcohol intoxication |

12 |

0.4% |

2.72% |

|||

|

elaboration |

11 |

0.53% |

5.39% |

|||

|

taking on responsibility on one’s own affairs |

172 |

8.35% |

84.31% |

|||

|

Shared TF |

AF* |

T-RF* |

M-RF* |

|||

|

integration |

AmE |

PenSp |

AmE |

PenSp |

AmE |

PenSp |

|

189 |

21 |

6.3% |

1.02% |

42.86% |

10.29% |

|

*AF= Absolute frequency per 3,000(AmE)/2,059 (PenSp) tokens of the culinary term type; *T-RF= Relative frequency per 3,000(AmE)/2,059 (PenSp) tokens of the cooking term type; *M-RF= relative frequency against the total number of metaphorical expressions.

Table 1 shows that stew is more frequently used metaphorically than its PenSp counterpart guisar, as 441 out of 3,000 stew citations have been tagged as metaphorical (14.7%), while in PenSp guisar was identified as metaphorical in 204 occurrences (9.91%) out of 2,059 tokens.

With regard to stewing metaphors, the metaphorical sense most frequently activated is integration (6.3%), mainly highlighting the amalgamation of a number of solid and liquid ingredients into a unified entity within stewing. Another TF frequently evoked by stew is musing on a subject (5.83%), where the thoughts or ideas about a certain problematic matter in a person’s mind are conceived of as food ingredients stewing over low heat in a cooking container for an extended period. This is followed by mental agitation (2.17%), in which a person’s worry and anxiety are envisioned as a liquid being stewed over low heat. Lastly, the least frequent metaphorical frame identified in AmE is alcohol intoxication (0.4%), which particularly refers to the effects of alcohol consumption.

As to the frequency of the metaphorical senses of guisar, table 1 also portrays that the most frequent one is taking on responsibility on one’s own affairs, activated by the metaphorical idiom yo me lo guiso, yo me lo como (8.35%). This is followed by integration is guisar/stewing (1.02%), present in both languages and substantially more salient in AmE (6.3%). Finally, the frame elaboration, referring to the process of elaboration implicated in stewing, is the least frequent metaphorical sense of guisar.

4. Discussion

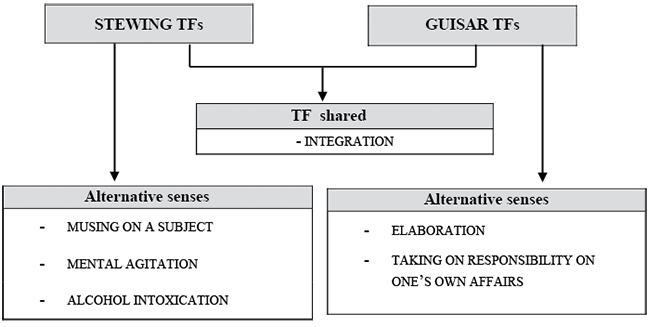

Both stew and guisar can evoke metaphorical senses stemming from the frame stew-guisar, as rendered in figure 7:

Fig. 7. TFs activated by stew and guisar

There is solely one metaphorical sense shared by AmE and PenSp, namely integration is guisar/stewing. This suggests each culture emphasises distinct experiential elements of the guisar/stewing frame.

Regarding AmE, it focuses on the entire process of stewing to conceptualise the musing on a subject, mental agitation and alcohol intoxication frames. The metaphor mental agitation is stewing closely resembles being angry is boiling, (see Esbrí-Blasco, 2020) as the SFs stewing and boiling highlight the process in which a negative emotion is conceived of as the hot liquid. Nevertheless, though the hot liquid is a core FE of both boiling and stewing, AmE particularly remarks the slow nature of stewing. Stewing implies gentle heat over a long period, while the necessary heat utilised when boiling is normally higher (resulting in stronger negative feelings than in stewing) and, consequently, a shorter boiling time.

Moreover, the focus on the complex and extended process of stewing also gives rise to the musing on a subject is stewing metaphor. When a person is mulling over a specific idea (usually a troubling situation) for an extended period of time, it could be conceptualised as though the thoughts regarding that circumstance were simmering over a gentle heat, just like food being stewed. Therefore, if someone is stewing on an idea, it implies that the person is engaged in a prolonged, introspective mental process similar to the activity of cooking a stew slowly. Just as a stew needs time and slow cooking to tenderize its ingredients and develop particular flavours, stewing on an idea or thought entails that the person is deep in thought, permitting the idea to slowly emerge, develop and become more refined over time. Thus, ideas, like stews, may reap the advantages of an extended period of slow, thoughtful stewing to reach their utmost potential or clarity.

The AmE idiom stew in one’s own juices, stemming as well from musing on a subject is stewing, lacks a corresponding idiom in PenSp.

Furthermore, stewing can express drug intoxication. In this regard, the results indicate that stewing solely refers to alcohol intoxication, as opposed to other cooking frames like baking, which usually refers to marijuana consumption (Esbrí-Blasco, Navarro i Ferrando, 2023).

With regard to guisar, PenSp makes use of this lexical unit to evoke the elaboration frame, which entails that PenSp deploys guisar to emphasise the intricate process of elaboration, akin to integration.

Interestingly, the only shared metaphor, integration is stewing/guisar, is activated in both languages by noun forms. The nouns stew and guiso are used to designate the varied components combined and integrated into a whole entity. Therefore, the results of the present study suggest the sole metaphor common to both languages is linguistically congruent since the word class involved in conveying the metaphorical sense of integration coincides. Otherwise, if a verb form is utilised in both languages, a distinct metaphorical interpretation is activated in either language.

As for the idioms found in the corpora, yo me lo guiso, yo me lo como and stew in your own juices, these may seem similar at first sight, but there are subtle differences in meaning in terms of the TFs evoked. The most prevalent metaphorical sense of guisar, expressed by yo me lo guiso, yo me lo como, lacks a direct counterpart in AmE. This idiom conveys the meaning of being self-reliant, taking control and taking full responsibility for your own actions. When someone says yo me lo guiso, yo me lo como, they do not rely on other people to handle a given situation, but they claim full accountability for the outcomes of their actions. Hence, this metaphorical sense indicates the speaker’s proactive stance.

A similar idiom found in AmE is stew in someone’s own juices, which conveys the idea of being left alone to endure the consequences or challenges of a troubling situation. In this metaphor, the process of being immersed in the negative emotions derived from the repercussions of your own actions is viewed as the ingredients of a stew being cooked slowly in its own juices. It conveys the idea of being isolated to confront the consequences without assistance or external interference. Therefore, this idiom suggests a more passive role.

All in all, the results indicate that stewing is more relevant in AmE than guisar in PenSp since, in this study, stew activated a significantly higher number of metaphorical expressions than guisar. Furthermore, it is important to note that stew and guisar exploit diverse metaphorical extensions in each language, as there is only one metaphorical sense shared by them. This indicates that while there may be some overlap in the metaphorical usage of stew and guisar, both lexical units diverge in their metaphorical extensions, reflecting the unique linguistic and cultural contexts in which they are utilised.

Conclusion

This study has explored metaphorical extensions of stew (AmE) and guisar (PenSp). The metaphorical senses identified in COCA and CEWD have been compared in both languages, thereby bringing to light the similarities and divergencies in terms of metaphorical conceptualisation across cultures. The metaphor analysis is based on comparing conceptual mappings between the SF and the TFs (see Esbrí-Blasco, Navarro i Ferrando, 2023). This study addresses the limitations identified in prior research by offering a cross-linguistic, in-depth, systematic analysis of the particular FEs participating in metaphorical correspondences.

The results of the current study suggest that the shared conceptual metaphor activated by stew and guisar (i.e., integration is stewing) is linguistically congruent and exhibits an equivalent level of linguistic elaboration in the languages under analysis. As for the non-shared metaphors, AmE utilises stew to display emotional and physiological responses (e.g., mental agitation is stewing and alcohol intoxication is stewing) and to refer to mental activity (e.g., musing on a subject is stewing). On the other hand, PenSp seems to place the experiential focus on TFs that focus on the development and different stages of the process, namely elaboration and emphasising personal agency of the process, as in the TF taking on responsibility on one’s own affairs.

Future research on culinary metaphors could expand the analysis to other word forms, not only culinary actions. Moreover, it could be worthwhile to contrast the use of the metaphorical senses in diverse genres or even modes of expression so as to facilitate a comprehensive evaluation of their degree of usage and applicability across a range of communicative contexts.

All in all, this study has provided deeper insights into the cross-linguistic variation of cooking metaphors, portraying the pivotal influence of culture in moulding human metaphorical patterns of conceptualisation across cultures.

References

Davies, M., 2008. The Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA): 600 million words, 1990-present. Available at: <https://www.english-corpora.org/coca/>. [Accessed 1 February 2023].

Davies, M., 2016. Corpus del Español: Two billion words, 21 countries. Available at: <https://www.corpusdelespanol.org/web-dial/>. [Accessed 1 February 2023].

Deignan, A., 2005. Metaphor and Corpus Linguistics. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Dobrovol’skij, D., Piirainen, E., 2022. Figurative Language: Cross-Cultural and Cross-Linguistic Perspectives. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter Mouton.

Esbrí-Blasco, M., 2020. Cooking in the Mind: a Frame-based Contrastive Study of Culinary Metaphors in American English and Peninsular Spanish. PhD thesis. Universitat Jaume I. http://doi.org/10.6035/14110.2020.189904.

Esbrí-Blasco, M., Navarro i Ferrando, I., 2023. Thematic Role Mappings in Metaphor Variation: contrasting English bake and Spanish hornear. Poznan Studies in Contemporary Linguistics, 59(1), pp. 43–64. https://doi.org/10.1515/psicl-2022-1020.

Fillmore, C. J., 1982. Frame Semantics. In: Linguistics in the Morning Calm. Ed. The Linguistic Society of Korea. Seoul: Hanshin, pp. 111–137.

Gibbs, R., 1999. Taking Metaphor Out of Our Heads and Putting it into the Cultural World. In: Metaphor in Cognitive Linguistics. Eds. R. Gibbs, G. Steen. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 145–166.

Ibarretxe-Antuñano, I., 2013. The Relationship between Conceptual Metaphor and Culture. Intercultural Pragmatics, 10 (2), pp. 315–339. https://doi.org/10.1515/ip-2013-0014.

Khajeh, Z., Ho-Abdullah, I., 2012. Persian Culinary Metaphors: A Cross-cultural Conceptualization. GEMA Online™ Journal of Language Studies, 12 (1), pp. 69–87. Available at: <https://ejournal.ukm.my/gema/article/view/22> [Accessed 15 December 2023].

Kövecses, Z., 2005. Metaphor in Culture: Universality and Variation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kövecses, Z., 2020. Extended Conceptual Metaphor Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lakoff, G., 1993. The Contemporary Theory of Metaphor. In: Metaphor and Thought. Ed. A. Ortony. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 202–251.

Lakoff, G., Johnson, M., 2003. Metaphors We Live By, Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Littlemore, J., 2019. Metaphors in the Mind: Sources of Variation in Embodied Metaphor. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108241441.

Pragglejaz Group, 2007. MIP: a Method for Identifying Metaphorically Used Words in Discourse. Metaphor and Symbol, 22 (1), pp. 1–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926480709336752.

Stefanowitsch, A., 2006. Corpus-based Approaches to Metaphor and Metonymy. In: Corpus-based Approaches to Metaphor and Metonymy. Eds. A. Stefanowitsch, S. Th. Gries. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 1–16.

Tsaknaki, O., 2016. Cooking Verbs and Metaphor Contrastive Study of Greek and French. Selected Papers on Theoretical and Applied Linguistics, 21, pp. 458–472. https://doi.org/10.26262/istal.v21i0.5242.

Van Valin, R., LaPolla, R. J., 1997. Syntax: Structure, Meaning & Function. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Yu, N., 2012. Metaphorical Expressions of Anger and Happiness in English and Chinese. In: Metaphor and Figurative Language, 3. Literary and Cross-Cultural Perspectives. Eds. P. Hanks, R. Giora. New York and London: Routledge, pp. 328–359.

Zhai, M., 2023. The Polysemy of Culinary Verbs in Spanish and Chinese: a Contrastive Study from the Cognitive-Linguistic Perspective. In: About Language: New Contributions to Linguistic Study. Eds. A. Ariño-Bizarro, N. López-Cortés, D. Pascual. Zaragoza: Prensas de la Universidad de Zaragoza, pp. 93–109.