Respectus Philologicus eISSN 2335-2388

2024, no. 46 (51), pp. 91–104 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15388/RESPECTUS.2024.46(51).7

London in the Novels by Robert Galbraith: a text-world perspective

Olga Kulchytska

Vasyl Stefanyk Precarpathian National University

Faculty of Foreign Languages

Shevchenko str. 57, 76018 Ivano-Frankivsk, Ukraine

Email: olga.kulchytska@gmail.com

ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9992-8591

https://ror.org/0576vga12

Research interests: Text World Theory; Pragmatics of Literary Texts; Contemporary Free Verse

Anna Erlikhman

International Humanitarian University

Faculty of Linguistics and Translation

Fontanska rd. 33, 65000 Odesa, Ukraine

Email: erlikhman.anna@gmail.com

ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8796-8107

https://ror.org/00811aj93

Research interests: Cognitive Linguistics; Discourse Analysis; Text Studies

Abstract. The Strike series of contemporary crime fiction novels by Robert Galbraith exhibits an abundance of descriptions of real-life London. The aim of this article is to explore their functions in the context of the author’s works.

Characteristic properties of the cityscapes in the novels are the merged perspectives of the omniscient narrator and a character, foregrounded details, contrasts in images and attitudes, and the use of metaphor and personification. Text World Theory allows us to explain how they aid in constructing mental representations, or text-worlds, of the city and examine functions fulfilled by the depictions of London in R. Galbraith’s fiction: (1) emphasising connectedness between the discourse- and text-worlds, (2) creating an atmospheric background, (3) broadening readers’ understanding of characters, (4) making London a character in its own right, (5) advancing the story. The first function is typical of all the text-worlds analysed; it indicates the real-world nature of fictional information as a distinctive feature of the Strike series.

Keywords: Robert Galbraith; the “Strike” novels; Text World Theory; descriptions of London; function.

Submitted 15 January 2024 / Accepted 14 June 2024

Įteikta 2024 01 15 / Priimta 2024 06 14

Copyright © 2024 Olga Kulchytska, Anna Erlikhman. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License CC BY-NC-ND 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

London is a major setting in the Strike series of crime novels by Robert Galbraith (J. K. Rowling). Only some of its locations are fictional; most of them exist in real life.

Fiction draws “material” from reality while simultaneously shaping our understanding of the real world (Charlton et al., 2011, p. 66). The current study aims to investigate the functions of real-life London portrayals in R. Galbraith’s novels from the perspective of Text World Theory (Werth, 1999; Gavins, 2007). The research database comprises 213 extracts from The Cuckoo’s Calling, The Silkworm, Career of Evil, Lethal White, Troubled Blood, and The Ink Black Heart (Galbraith, 2013; 2014; 2015; 2018; 2020; 2022 respectively). The objectives of the research are as follows: to examine the author’s approach to presenting the city; to foster an understanding of the purposes of particular descriptions of the cityscapes, even when some of them have little or no relation to the plot.

The relevance of this study is determined by readers’ interest in R. Galbraith’s works and critics’ attention to the phenomenon of the city in fiction. Approaches to presenting the city in literature vary from those focusing on the background (McManis, 1978), setting the atmosphere (Martin, 1965, p. 214), to a personified entity (Augustine, 1991, pp. 73–74), a character “personified and dramatised in its own right” (Tromanhauser, 2004, p. 33). It is argued that there exists a psychological interrelation between the individual and the city (Oates, 1981, p. 11). The depiction of an iconic capital can serve to stimulate readers’ interest in a book (Calabrese and Rossi, 2015).

In literary works, London is shown in diverse, often contrasting ways to reflect the multifaceted nature of the city. In Charles Dickens’s novels, it is a virtual Dickensian City, imagined urban world models, a space which exposes hidden social truths (Murail and Thornton, 2017, p. 5). In The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson, the city is a place where wealth and poverty coexist under the masks of respectability or squalor (Wall, 2015, p. 159). In Mrs. Dalloway by Virginia Woolf, the image of London conveys the coming of a new postwar era; its physical world seems to adjust itself to the characters’ interpretations of events (Brown, 2015, pp. 22, 34). Authors can adopt similar approaches to portraying London. For instance, its voices, noises, and sounds in Charles Dickens’s fiction find parallels in the pictures drawn by Virginia Woolf (Orestano, 2021). Peter Ackroyd uses the concept of the city as background and a shaping force in the lives of his characters (Rosenstock, 2013, p. 131); in Hawksmoor, he offers a trans-generic understanding of London as a mythical entity, “the written trace and existential/social/historical vagrancy” (Champion, 2008, pp. 36–37).

The central claim of this study is that the depictions of London in the novels by R. Galbraith exemplify the real-world nature of fictional information, make a “bridge” between reality and literary discourse. In addition, the author uses descriptions to create an atmospheric background, deepen readers’ understanding of characters, make the city a character in its own right, and propel the story.

1. Research methodology and method of analysis

Numerous cityscapes in the Strike novels enable readers to construct vivid mental representations in their minds; therefore, the framework chosen for analysis is Text World Theory (henceforth, we will use TWT throughout the paper) by Paul Werth and Joanna Gavins.

TWT (Werth, 1999; Gavins, 2007; 2020; Gavins and Lahey, 2016) separates discourse into distinct conceptual levels: the discourse-world and the text-world. The former represents the physical environment in which participants (the author and readers) communicate through text. Text-worlds are mental representations based on textual information and readers’ knowledge of the real world. World-builders include time, location, enactors/characters, and objects. The relationships among them are expressed by relational processes x is y; x has y; x is on/at/with y; function-advancing propositions propel the discourse, describing events, actions, and states. Changes in spatiotemporal parameters and the introduction of new enactors and objects cause world-switches; alterations in attitude lead to the emergence of “modal-worlds” (Gavins, 2007, pp. 91–110). Metaphors are viewed as conceptual double-vision, concurrent mental spaces of the initial text-world and the metaphorical blended world. Text-worlds whose reliability can be verified in the discourse-world are participant-accessible; text-worlds produced by enactors with no counterparts in the discourse-world are enactor-accessible (Gavins, 2007, pp. 77–78; Gavins and Lahey, 2016, p. 4; Vermeulen, 2022, p. 574).

One of the aims of TWT is to discuss the relationship between the discourse- and text-worlds. For instance, Jessica Norledge (2011–2012) shows that a reader builds text-worlds, mapping connections from the discourse-world. Kelly Hallam (2013) suggests that there is no ontological distinction between “reality” and “fiction” in R. Coover’s Matinée. Ernestine Lahey (2016) contends that the text-world can be an element in the formation of the discourse-world. Patricia Canning (2017) argues that text-worlds can reify the discourse-world knowledge. Alison Gibbons (2019) illustrates how ethical responses to literary discourse can exert an effect in the real world. Alison Gibbons and Sara Whiteley (2021) examine direct address as a means of breaking the fourth wall.

The current analysis of descriptions of real-life London in R. Galbraith’s fiction involves the following steps:

• compiling a database of extracts from six novels by R. Galbraith (2013; 2014; 2015; 2018; 2020; 2022);

• examining characteristic properties of the depictions: different perspectives, level of detail, contrasts, the potential for symbolic or metaphorical interpretation, and personification;

• explaining the functions of Londonscapes in the novels. This step employs the concepts of the text-world (world-builders, relational processes, function-advancing propositions), world-switches, modal-worlds, metaphor as double vision, and free indirect discourse (Gavins, 2007, pp. 35–72, 126–143, 146–162; 2020, pp. 3–6, 15–17, 125–147).

2. R. Galbraith’s approach to portraying London

The two protagonists of R. Galbraith’s crime novels are private detectives Cormoran Strike and Robin Ellacott, and the primary setting of the action is London.

The city in the novels is as diverse as the British capital itself: respectable and working-class quarters; streets, parks, squares; the Thames; historical and cultural landmarks; iconic structures and edifices; upmarket and cheap shops; markets; clubs, pubs, restaurants, cafés, bars; the public transport system. London is depicted as beautiful; for instance, “the misty dome of St Paul’s shone like a rising moon” (Galbraith, 2014, p. 106). At the same time, the city is not romanticised; by way of illustration, the junction of Charing Cross Road and Tottenham Court Road is shown as everlasting roadworks with chunks of rubble, hardboard tunnels, narrow walkways, metal fences (Galbraith, 2013, pp. 13, 290; 2015, p. 7), which aligns with the construction of a new rail line in this part of London in the 2010s. The city’s darker sides are neither glossed over nor overemphasised; for example, in Soho, “[m]en in sleeping bags glared at [Strike] as he moved far closer than members of the public usually dared” (Galbraith, 2015, p. 173).

R. Galbraith’s cityscapes are characterised by:

• Different perspectives. Text-worlds of locations are participant-accessible and enactor accessible. The former represents the perspective of the omniscient narrator; the latter of an enactor. They can merge within the same extract, creating free indirect discourse; for example, the Walkie Talkie on Fenchurch Street has a roof garden and a restaurant (the narrator’s view); in Strike’s opinion, it is a building “of notable and unapologetic ugliness, with a concave face” (Galbraith, 2022, p. 346). Both perspectives can include concrete sensory details and abstract thoughts and feelings (Prince, 2001, p. 44). For instance, Denmark Street is described as short with colourful shop windows (Galbraith, 2013, p. 13), Strike associates the Tottenham pub with escape and refuge (Galbraith, 2013, p. 364).

• Some descriptions are notably detailed. For instance, the Tottenham pub (renamed The Flying Horse in 2015) features gleaming scrolled dark wood, brass fittings, frosted glass half-partitions, leather banquettes, bar mirrors covered in gilt, cherubs, horns of plenty, the garish glass cupola, a large painting of a jolly Victorian maiden (Galbraith, 2013, p. 48). Alternatively, a minimal number of details essential for a particular discourse purpose are used, such as spotlighting the night city: the neon blue London Eye, ruby windows of the Oxo Tower, the golden light of the Southbank Centre, Big Ben, and the Palace of Westminster (Galbraith, 2014, p. 118). While some details may seem insignificant or inappropriate (the men’s toilet in the Tottenham pub smelling of piss, flyers for bands on the walls of Flitcroft Street (Galbraith, 2014, p. 403; 2013, p. 48), and others), they collectively contribute to shaping the mental image of the city.

• The device of contrast is frequently employed; for example, “bustling and essentially soulless” King Street is ten minutes’ walk from “a sleepy, countrified stretch of the Thames embankment” (Galbraith, 2013, p. 140). Contrast can be expressed through the characters’ intellectual/emotional responses to reality, as shown by Robin’s part amusement, part disapproval when she finds out that upmarket Pratt’s Club still favours men over women (Galbraith, 2018, pp. 111, 114).

• Certain objects are personified; for instance, the monument to Queen Victoria frowns at Robin, disapproving of her confusion and hangover (Galbraith, 2015, p. 181).

• Some portrayals invite symbolic or metaphorical interpretations, two representative examples being a figure of a pelican plucking at her own breast to feed her chicks with her blood (a symbol of maternal love) on Baroness de Munck’s headstone in Highgate Cemetery (Galbraith, 2022, p. 647) and Smithfield Market perceived as a “temple to meat” (Galbraith, 2014, p. 4).

TWT analysis allows us to explain how the properties mentioned above enhance the expressiveness of particular text-worlds and to examine the functions of London descriptions in R. Galbraith’s discourse.

3. Functions of the cityscapes in the Strike series

The same cityscape can perform two or more functions simultaneously. For the purpose of the article, only one of them is discussed in each subsection below.

3.1 Connecting the discourse- and text-worlds

This function is observed consistently across all cases analysed in our study. It can be performed by any text-world containing empirically verifiable locations/objects. However, it is most evident in depictions unrelated to the plot or characters.

For instance, in The Cuckoo’s Calling (Galbraith, 2013, p. 154) and Career of Evil (Galbraith, 2015, p. 462), there are almost identical pictures of Epstein’s sculpture Day on the 55 Broadway building.

Strike sits in the Feathers, the pub near New Scotland Yard, whose window looks out onto

a great grey 1920s building decorated with statues by Jacob Epstein. The nearest of these sat over the doors, and stared down through the pub windows; a fierce seated deity was being embraced by his infant son, whose body was weirdly twisted back on itself, to show his genitalia. Time had eroded all shock value. (Galbraith, 2013, p. 154).

The object’s details are specified by relational processes: “by Jacob Epstein”, “fierce”, “embraced”, “infant”, “weirdly twisted”, and others. The function-advancing propositions “[the statue] stared” and “Time had eroded all shock value” are markers of personification. There are several indications that the figure is viewed from the main enactor’s perspective: “The nearest” statue, a “fierce” deity, his “son”. The sculpture is described twice, yet in neither novel is this text-world related to the story.

Other examples of seemingly irrelevant places and objects in the Strike novels are the statue of Freddie Mercury over the entrance to the Dominion Theatre (Galbraith, 2013, p. 47), which was removed from its real-life location in 2014; the Chilled Eskimo pub (Galbraith, 2014, p. 151); a sculpture of a cat sitting atop the Catford Shopping Centre sign (Galbraith, 2015, p. 392); “gigantic, crumbling stone skulls” on gateposts of St Nicholas’s churchyard (Galbraith, 2018, p. 56).

According to Raymond Williams (1973, p. 154), the true significance of the city is “double condition: the random and the systematic, the visible and the obscured”, which may explain why readers’ attention is drawn to things that have little or no relation to the plot. Some objects appear to be picked randomly; some are accentuated by the author, while others are just named and remain unexplained. Nonetheless, all of them are part of the unfolding picture of contemporary London. The city is shown as an entity that is important in itself: it plays its social roles and is capable of producing a vivid image.

3.2 Atmospheric background to events described

The depiction of Smithfield Market and the Smithfield Café in Silkworm is an example of how the images of London are used to provide an authentic setting and to create an atmosphere in a story.

Strike has been on his feet all night; at about 6.30 a.m., he enters Long Lane and goes

towards Smithfield Market, monolithic in the winter darkness, a vast rectangular Victorian temple to meat, where from four every weekday morning animal flesh was unloaded, as it had been for centuries past, cut, parcelled and sold to butchers and restaurants across London. Strike could hear voices through the gloom, shouted instructions and the growl and beep of reversing lorries unloading the carcasses. (...)

(...) [A] stone griffin [stood] sentinel on the corner of the market building. Across the road, glowing like an open fireplace against the surrounding darkness, was the Smithfield Café, open twenty-four hours a day, a cupboard-sized cache of warmth and greasy food.

(...)

Exhausted and hungry, he turned at last, with the pleasure that only a man who has pushed himself past his physical limits can ever experience, into the fat-laden atmosphere of frying eggs and bacon.

(...)

He ate gazing dreamily at the market building opposite. The nearest arched entrance, numbered two, was taking substance as the darkness thinned: a stern stone face, ancient and bearded, stared back at him from over the doorway. Had there ever been a god of carcasses? (Galbraith, 2014, pp. 4–5).

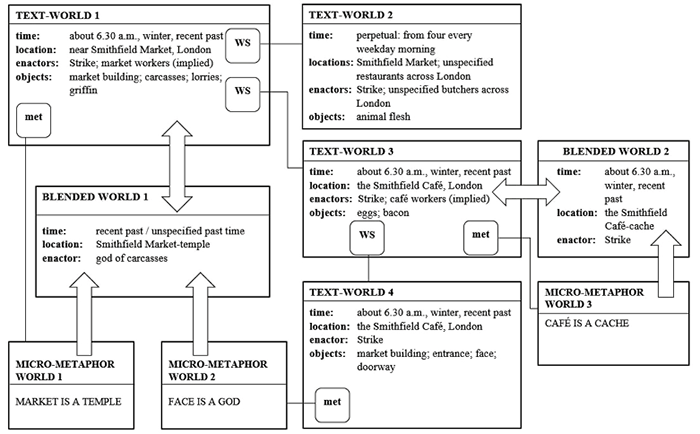

Three diagrams below are drawn according to the principles suggested by P. Werth (1999, pp. 109, 123) and J. Gavins (2007, pp. 40–47, 55–70, 80, 134, 158).

Fig. 1. Text-worlds of Smithfield Market and the Smithfield Café in Silkworm by R. Galbraith.

The description contains four text-worlds: Smithfield Market, a world-switch to London meat buyers, a world-switch to the Smithfield Café, and a world-switch back to the market as seen from the café. Initially, these are the omniscient narrator’s presentations of real-life locations. As argued below, three micro-metaphor worlds are created by the enactor (Strike) rather than the narrator. They form blended metaphor worlds that feed into the initial text-worlds of the market and the café.

The omniscient narrator uses world-builders – locations and objects (Long Lane, “Smithfield Market”, “the Smithfield Café”, “restaurants across London”, “Across the road”, “flesh”, “griffin”, “entrance”) – to provide basic information about the places. Some relational processes are also provided by the narrator (“vast rectangular Victorian”, “from four every weekday morning”, “on the corner of the market building”, “open twenty-four hours a day”, “arched”). At the same time, the picture is given through the protagonist’s perception, such as vision: “glowing like an open fireplace against the surrounding darkness”; hearing: “beep of reversing lorries”; smell: “the fat-laden atmosphere of frying eggs and bacon”; taste: “greasy food”; feeling of space and temperature: “a cupboard-sized cache of warmth”, and other examples of relational processes and function-advancing propositions. The distinction between the two perspectives in the free indirect discourse occasionally blurs; for instance, “beep of reversing lorries” and “greasy food” can belong to both perspectives simultaneously.

The importance of the enactor’s interpretation is emphasised by the question, “Had there ever been a god of carcasses?”. The perception of a carved face as a god indicates that the metaphors FACE IS A GOD and MARKET IS A TEMPLE originate from the enactor rather than the narrator. Likewise, CAFÉ IS A CACHE is his creation: he knows where night workers can obtain hot food. In each instance, metaphoric meaning invokes semantic tension when linguistic items are placed in novel contexts (Matiiash-Hnediuk et al., 2024, p. 1). There are other indicators of free indirect discourse in this extract. The relational process “cupboard-sized” and the function-advancing proposition “stone face … stared back at him” imply access to Strike’s mind: he perceives the café from the perspective of an exceptionally tall and muscular man; he is tired but imaginative as ever. The picture is anchored to the enactor’s deictic centre. At first, he sees the café from the darkness of the street; with the coming of daylight, the entrance to the market becomes more discernible to his eye.

The text-worlds involve contrasts: big market versus small café, the physical versus the transcendent. Two details – a griffin and a stone face – are foregrounded in text-worlds 1 and 4. In the blended metaphor world 1, the stone face is personified, becoming an enactor.

The function of atmospheric background is revealed through the interrelation of the world-builders, relational processes, and function-advancing propositions. The depiction of the working city draws on the real-world nature of the images. Free indirect discourse (two different perspectives, including the blended metaphor worlds, which feed into text-worlds 1 and 3) creates a complex ambiance of prosaic work and mystery. The latter is intensified by the repetition of “darkness” as nighttime may be associated with ethereal matters.

3.3 Broadening readers’ understanding of characters

Particular cityscapes in the Strike series highlight relations between three world-building elements: location, enactor(s), and objects.

For example, in Lethal White, Robin goes undercover to investigate a case of blackmail at the Palace of Westminster. She experiences a panic attack triggered by the suspect’s behavior, as a past trauma (rape and attempted murder) has left her vulnerable. In a beautiful chamber, she struggles to perceive her surroundings adequately.

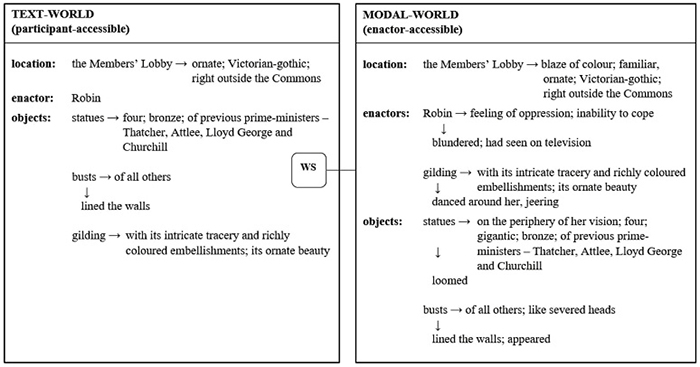

She had blundered into a blaze of gold and colour that was increasing her feeling of oppression. The Members’ Lobby, that familiar, ornate, Victorian-gothic chamber she had seen on television, stood right outside the Commons, and on the periphery of her vision loomed four gigantic bronze statues of previous prime ministers – Thatcher, Attlee, Lloyd George and Churchill – while busts of all the others lined the walls. They appeared to Robin like severed heads and the gilding, with its intricate tracery and richly coloured embellishments, danced around her, jeering at her inability to cope with its ornate beauty. (Galbraith, 2018, p. 169).

The location is viewed through the eyes of the enactor. However, her modal-world represents a switch from the initial text-world of the real-life place. The reality – the location of the Lobby, the statues of the prime ministers, the location of the busts – merges with the character’s distorted perception. The relational processes “familiar chamber”, “gigantic statues”, “busts like severed heads”, and the function-advancing proposition “the statues loomed” indicate the enactor-accessible nature of the epistemic modal-world. Meanwhile, the initial text-world is participant-accessible. In Robin’s mind, the objects are personified: gilding, tracery, and embellishments “danced around her, jeering at her” (function-advancing propositions). These are intention processes that transform the objects into enactors. The statues and busts are brought into focus; other details are blurry – reflection of the protagonist’s emotional and physical state. The two text-worlds are contrasted: familiar and beautiful versus scary and elusive.

The function of explaining the character is foregrounded by the juxtaposition of the initial participant-accessible text-world and the enactor-accessible epistemic modal-world.

Fig. 2. Text-worlds of the Members’ Lobby in Lethal White by R. Galbraith.

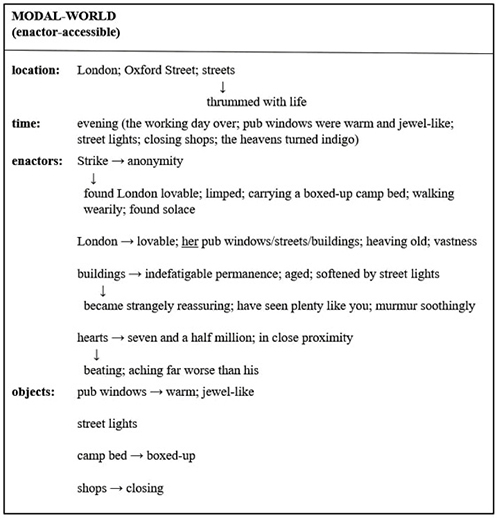

In Figures 2 and 3, the symbols → and ↓stand for relational processes and function-advancing propositions respectively.

3.4 The city as a character

The following passage from The Cuckoo’s Calling exemplifies how the city is converted into an active character.

Strike’s private life has collapsed; he is close to bankruptcy, currently homeless, and has to sleep on a camp-bed in his office.

This was the hour when he found London most lovable; the working day over, her pub windows were warm and jewel-like, her streets thrummed with life, and the indefatigable permanence of her aged buildings, softened by the street lights, became strangely reassuring. We have seen plenty like you, they seemed to murmur soothingly, as he limped along Oxford Street carrying a boxed-up camp bed. Seven and a half million hearts were beating in close proximity in this heaving old city, and many, after all, would be aching far worse than his. Walking wearily past closing shops while the heavens turned indigo above him, Strike found solace in vastness and anonymity. (Galbraith, 2013, p. 58)

Fig. 3. Text-world of personified London in The Cuckoo’s Calling by R. Galbraith.

The contrasting details of “warm and jewel-like” pub windows versus “closing shops” are temporal linguistic cues. The city is presented from the protagonist’s perspective. London is simultaneously the location and an enactor in his epistemic modal-world. Its enactor status is revealed through several relational processes and function-advancing propositions: the pronoun her in reference to the “indefatigable”, “heaving old city”, which is capable of being “reassuring”; its buildings “murmur soothingly”; they observe and assess citizens, “We have seen many like you”. Strike agrees (the parenthesis “after all” indicates access to his mind): many people suffer more than he does. He finds “solace” in the interaction. Thus, the city becomes a character in its own right as it features the properties of an enactor in the protagonist’s modal-world.

3.5 Advancing a story

World-building elements within city portrayals can propel a story, as shown in the examples from Troubled Blood (Galbraith, 2020).

A female doctor disappeared in Clerkenwell back in 1974. Departing from the St John’s Medical Practice, she intended to meet a friend at the Three Kings pub but did not arrive there. It is a forty-year-old case, but Strike and Robin prove that the doctor was murdered.

The detectives retrace the victim’s route. Twelve real-life locations on their way are described in the novel: St John’s Lane, Passing Alley, St John’s Gate, Clerkenwell Road, Albemarle Way, St John Priory Church and the Memorial Garden, Jerusalem Passage, Aylesbury Street, Clerkenwell Green, Clerkenwell Close, and the Three Kings pub (Galbraith, 2020, pp. 140–156). Some of them are presented by the omniscient narrator; others, from the protagonists’ perspective; however, the places are verifiable. Taken together, they form a ramified Clerkenwell text-world; in addition to setting the background of the action, they advance the story.

The enactors’ movements from place to place create new world-switches. Each new location has its own relational processes. For example, Passing Alley is a “dark, vaulted corridor through the buildings”; Clerkenwell Green is “a wide rectangular square with trees, a pub and a café. Two telephone boxes [stand] in the middle” (Galbraith, 2020, p. 142, 152). Each text-world is a step in the investigation.

The relatively short descriptions of the streets make the narrative dynamic. They are contrasted with more detailed pictures of the Memorial Garden and the Three Kings pub (Galbraith, 2020, p. 148, 156). The most prominent details of the garden are medicinal herbs and a figure of Christ surrounded by the emblems of the evangelists. The interior of the pub is shown as perceived by Robin: among other details, she pays attention to the photographs of the famous musicians of the 1970s – Bowie, Bob Marley, Bob Dylan, and Jimi Hendrix. They allude to Strike’s origins as an illegitimate son of a rock star, a backstory in the series, and to the era of the investigated crime. They may have symbolic interpretations, suggesting themes of life and death, past and present.

The story-advancing function is manifested through a succession of text-worlds related to the same plot line. Eventually, we learn that a red telephone box at the junction of Albemarle Way and Clerkenwell Road (a real-life object) was the murderess’s hiding place, and she used herbs (not necessarily from the Memorial Garden) as a weapon.

Repetition of a world-building element can suggest a hypothetical plot line. For example, the Maltese cross decorates real-world places – St John’s Gate, St John’s Square, the courtyard of Hampton Court Palace; and a fictional place – a gazebo in the missing woman’s garden (Galbraith, 2020, p. 148, 457, 489). The cross is a symbol, “[mediator] between the natural and the transcendental worlds” (Astrauskienė, Šležaitė, 2013, p. 67). In the novel, a medium says that the missing woman “lies in a holy place” (Galbraith, 2020, p. 52). This may generate an association with the Maltese cross and suggest further direction of events.

Conclusion

One of the notable features of R. Galbraith’s crime series is the abundance of descriptions of real-life London locations. The city is shown as a complex physical, social, and cultural phenomenon, which is a representative example of the connectedness between reality and literary discourse.

The exact portrayal of London can serve several purposes at a time. The function performed by any depiction is presenting the authenticity of London, connecting the discourse- and text-worlds. It is best, but not exclusively, conveyed through examples without a direct relationship to the plot. The importance of this function is indicated by the fact that pictures of participant-accessible locations are copious in number, and information about them can be verified. The city in the Strike novels is not “the London of Robert Galbraith”; it is a complex real-world urban entity and is described as such. Its iconic locations, unique structures and edifices make it highly recognisable. Along with well-known places and objects, R. Galbraith draws attention to particular or minor details, which might seem insignificant or irrelevant, but they are part of the discourse-world. Thus, the way the author shows London initiates interpretive processes that create mental representations of the famous city, which possesses its own identity and importance.

Simultaneously with the above function, presentations of checkable locations are used for other purposes. Many of them are backgrounds for the action and/or create an authentic atmosphere of the city. The interaction between locations and enactors not only enhances the capability of descriptions to deepen readers’ understanding of characters but also makes the city a character in its own right. These cases are complex as readers receive images of verifiable locations filtered through enactors’ minds. It is suggested in the article that within the same picture, there can be two interlaced text-worlds – participant-accessible and enactor accessible, both sharing the same world-builders. Last but not least, there are depictions that help propel the story, providing essential information for the development of the plot.

In this article, the potential coexistence of participant-accessible and enactor-accessible worlds within the same extract has not been closely examined. In addition, it would be of interest to conduct more detailed research into the plot-advancing function of cityscapes in fiction. Currently, these two issues appear to be promising avenues for study.

Sources

Galbraith, R., 2013. The Cuckoo’s Calling. London: Sphere.

Galbraith, R., 2014. The Silkworm. London: Sphere.

Galbraith, R., 2015. Career of Evil. London: Sphere.

Galbraith, R., 2018. Lethal White. London: Sphere.

Galbraith, R., 2020. Troubled Blood. London: Sphere.

Galbraith, R., 2022. The Ink Black Heart. London: Sphere.

References

Astrauskienė, J., Šležaitė, I., 2013. Appropriation of Symbol as Disclosure of the World of the Play in Tennessee Williams’s “The Glass Menagerie”. Respectus Philologicus, 23(28), pp. 67–82. https://doi.org/10.15388/RESPECTUS.2013.23.28.6. Available at: <https://www.zurnalai.vu.lt/respectus-philologicus/article/view/13842/12761> [Accessed 1 February 2023].

Augustine, J., 1991. From Topos to Anthropoid: The City as Character in Twentieth-Century Texts. In: City Images: Perspectives from Literature, Philosophy and Film. Ed. M. A. Caws. New York: Gordon and Breach, pp. 73–86. Available at: <https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/edit/10.4324/9781315075136/city-images-mary-ann-caws> [Accessed 1 February 2023].

Brown, P. T., 2015. The Spatiotemporal Topography of Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway: Capturing Britain’s Transition to a Relative Modernity. Journal of Modern Literature, 38(4), pp. 20–38. https://doi.org/10.2979/jmodelite.38.4.20. Available at: <https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2979/jmodelite.38.4.20?seq=1> [Accessed 1 February 2023].

Calabrese, S., Rossi, R., 2015. Dan Brown: Narrative Tourism and “Time Packaging”. International Journal of Language and Linguistics, 2 (2), pp. 30–38. Available at: <https://ijllnet.com/journals/Vol_2_No_2_June_2015/4.pdf> [Accessed 12 June 2023].

Canning, P., 2017. Text World Theory and Real World Readers: From Literature to Life in a Belfast Prison. Language and Literature, 26(2), pp. 172–187. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963947017704731.

Champion, M. G., 2008. In the Beginning was the (Written) Word: Peter Ackroyd’s Hawksmoor as a Myth of Creation. Orbis Litterarum, 63(1), pp. 22–45. Available at: <https://www.academia.edu/13738044/In_the_Beginning_was_the_Written_Word_Peter_Ackroyds_Hawksmoor_as_a_Myth_of_Creation> [Accessed 22 April 2023].

Charlton, E., Wyse, D., Cliff Hodges, G., Nikolajeva, M., Pointon, P. and Taylor, L., 2011. Place-Related Identities Through Texts: From Interdisciplinary Theory to Research Agenda. British Journal of Educational Studies, 59(1), pp. 63–74. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2010.529417.

Gavins, J., 2007. Text World Theory: An Introduction. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press Ltd. Available at: <https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3366/j.ctv1c29rv5> [Accessed 4 January 2022].

Gavins, J., 2020. Poetry in the Mind: The Cognition of Contemporary Poetic Style. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. Available at: <https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3366/j.ctt1r285f> [Accessed 18 September 2022].

Gavins, J., Lahey, E., 2016. World Building in Discourse. In: World Building: Discourse in the Mind. Eds. J. Gavins, E. Lahey. London, Oxford, New York, New Delhi, Sydney: Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 1–13. Available at: <https://www.google.com.ua/books/edition/World_Building/hW46DAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=Gavins,+J.,+Lahey,+E.,+2016.+World+building+in+discourse.&printsec=frontcover> [Accessed 5 September 2022].

Gibbons, A., 2019. Using Life and Abusing Life in the Trial of Ahmed Naji: Text World Theory, Adab and the Ethics of Reading. Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA). [online] Available at: <https://shura.shu.ac.uk/23999/3/Gibbons-UsingLifeAbusingLife%28AM%29.pdf> [Accessed 5 June 2023].

Gibbons, A., Whiteley, S., 2021. Do Worlds Have (Fourth) Walls? A Text World Theory Approach to Direct Address in Fleabag. Language and Literature: International Journal of Stylistics, 30(2), pp. 105–126. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963947020983202.

Hallam, K., 2013. A Text World Theory Analysis of Robert Coover’s ‘Matinée’. Master’s thesis. University of Nottingham. Available at: <https://www.academia.edu/16536076/A_Text_World_Theory_Analysis_of_Robert_Coovers_Matin%C3%A9e> [Accessed 27 July 2023].

Lahey, E., 2016. Author-Character Ethos in Dan Brown’s Langdon-Series Novels. In: World Building: Discourse in the Mind. Eds. J. Gavins, E. Lahey. London, Oxford, New York, New Delhi, Sydney: Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 33–52. Available at: <https://www.google.com.ua/books/edition/World_Building/Wmw6DAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=Lahey.+Author %E2%80%8Bcharacter+ethos+in+Dan+Brown%E2%80%99s+Langdon-%E2%80%8Bseries+novels.&pg=PA33&printsec=frontcover> [Accessed 5 December 2022].

Martin, R. E., 1965. The Fiction of Joseph Hergesheimer. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. Available at: <https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv512tk4> [Accessed 22 February 2023].

Matiiash-Hnediuk, I., Soloviova, T., Bilianska, I. and Yurchyshyn, V., 2024. Conceptualizing Parenthood: American Newspaper Discourse Analysis. Forum for Linguistic Studies, 6(1), pp. 1–16. https://doi.org/10.59400/fls.v6i1.1987.

McManis, D. R., 1978. Places for Mysteries. Geographical Review, 68(3), pp. 319–334. https://doi.org/10.2307/215050.

Murail, E., Thornton, S., 2017. Dickensian Counter-Mapping, Overlaying, and Troping: Producing the Virtual City. In: Dickens and the Virtual City: Urban Perception and the Production of Social Space. Eds. E. Murail, S. Thornton. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 3–32. Available at: <https://www.academia.edu/36226192/Dickensian_Counter_Mapping_Overlaying_and_Troping_Producing_the_Virtual_City> [Accessed 6 February 2023].

Norledge, J., 2011–2012. Thinking Outside of the Box: A Text World Theory Response to the Interactivity of B. S. Johnson’s The Unfortunates. Innervate, 4, pp. 51–61. Available at: <https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/english/documents/innervate/11-12/1112norledgecognitivepoetics.pdf> [Accessed 15 August 2023].

Oates, J. C., 1981. Imaginary Cities: America. In: Literature and the American Urban Experience: Essays on the City and Literature. Eds. M. C. Jaye, A. C. Watts. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press. pp. 11–33. Available at: <https://www.google.com.ua/books/edition/Literature_the_American_Urban_Experience/BxHpAAAAIAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=Oates.+Imaginary+Cities:+America&pg=PA11&printsec=frontcover> [Accessed 28 February 2023].

Orestano, F., 2021. The Roaring Streets: Dickensian London in the Pages of Virginia Woolf. OpenEdition. Sounds Victorian: Acoustic Experience in 19th-Century Britain. [online] Available at: <https://journals.openedition.org/cve/9870> [Accessed 7 April 2023]. https://doi.org/10.4000/cve.9870.

Prince, G., 2001. A Point of View on Point of View or Refocusing Focalization. In: New Perspectives on Narrative Perspective. Eds. W. van Peer, S. Chatman. Albany: State University of New York Press. pp. 43–50. Available at: <https://www.google.com.ua/books/edition/New_Perspectives_on_Narrative_Perspectiv/yRFkmJD12SQC?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=Prince.+A+Point+of+View+on+Point+of+View+or+Refocusing+Focalization&pg=PA43&printsec=frontcover> [Accessed 17 August 2022].

Rosenstock, M., 2013. Peter Ackroyd’s Hawksmoor (1985) and the Case of the Lost Detective. In: Adventuring in the Englishes: Language and Literature in a Postcolonial Globalized World. Eds. I. A. Elsherif, P. M. Smith. Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 130–145. Available at: <https://www.academia.edu/37894112/Peter_Ackroyds_Hawksmoor_1985_and_the_Case_of_the_Lost_Detective> [Accessed 22 April 2023].

Tromanhauser, V., 2004. Virginia Woolf’s London and the Archaeology of Character. In: The Swarming Streets: Twentieth-Century Literary Representations of London. Ed. L. Phillips. Amsterdam – New York: Rodopi, pp. 33–43. Available at: <https://www.google.com.ua/books/edition/The_Swarming_Streets/av6zGhIlumoC?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=Tromanhauser.+Virginia+Woolf%E2%80%99s+London+and+the+archaeology+of+character.&pg=PA33&printsec=frontcover> [Accessed 23 April 2023].

Vermeulen, K., 2022. Growing the Green City: A Cognitive Ecostylistic Analysis of Third Isaiah’s Jerusalem (Isaiah 55–66). Journal of World Languages, 8(3), pp. 567–592. https://doi.org/10.1515/jwl-2022-0025.

Wall, B., 2015. ‘The Situation was Apart from Ordinary Laws’: Culpability and Insanity in the Urban Landscape of Robert Louis Stevenson’s London. Journal of Stevenson Studies, 12, pp. 147–169. Available at: <https://robert-louis-stevenson.org/wp-content/uploads/2016-stevenson-journal-vol-12.pdf> [Accessed 22 March 2023].

Werth, P., 1999. Text Worlds: Representing Conceptual Space in Discourse. New York: Longman Education Inc. Available at: <https://textworldtheory.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/text-worlds.pdf> [Accessed 9 February 2022].

Williams, R., 1973. The Country and the City. New York: Oxford University Press. Available at: <https://archive.org/details/countrycity0000will_j1q5> [Accessed 18 March 2023].