Respectus Philologicus eISSN 2335-2388

2024, no. 45 (50), pp. 110–125 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15388/RESPECTUS.2024.45(50).10

Rendering of Verbal and Verbal-Visual Puns in Lithuanian-Dubbed Animated Film “Mr. Peabody & Sherman”

Brigita Brasienė

Vilnius University Kaunas Faculty

Muitinės st. 8, LT-44280 Kaunas, Lithuania

Email: brigita.brasiene@knf.stud.vu.lt

ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/my-orcid?orcid=0009-0006-3593-2336

Scientific interests: Slang translation, Culture-specific items translation, Audiovisual translation, Dubbing, Translation of puns, Untranslatability

Abstract. The rendering of verbal and verbal-visual puns in dubbing is a tough task that requires taking into account linguistic challenges, multimodal cohesion and dubbing synchronies. Thus, the aim of this research is to determine how verbal and verbal-visual puns are rendered from English into Lithuanian in the animated film Mr. Peabody & Sherman (2014). There have been collected 27 cases of puns including 14 verbal (52%) and 13 verbal-visual (48%) puns. The categorisation of verbal and verbal-visual puns according to the type revealed that verbal puns contained examples of homonymy, homophony and paronymy, but paronymic verbal puns prevailed the most. Almost all cases of verbal-visual puns were homonymic because of their intersemiotic construction which is usually based on polysemous words. All cases of verbal and verbal-visual puns have been rendered by employing 3 translation techniques: PUN→PUN, PUN→NON-PUN, PUN→PUNOID. The prevailing technique for transferring verbal and verbal-visual puns was PUN→PUN, which reveals the translator’s attempt to tackle linguistic challenges and consider multimodal cohesion and dubbing synchronies.

Keywords: audiovisual translation; dubbing; translation of puns; verbal puns; verbal-visual puns.

Submitted 31 July 2023 / Accepted 14 March 2024

Įteikta 2023 07 31 / Priimta 2024 03 14

Copyright © 2024 Brigita Brasienė. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License CC BY 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

The rendering of verbal and verbal-visual puns in dubbing is a very difficult task that requires taking into account linguistic challenges, multimodal cohesion and dubbing synchronies. Thus, the aim of the research is to determine how verbal and verbal-visual puns are rendered from English into Lithuanian in the animated film Mr. Peabody & Sherman. The objectives of the research are as follows: to define verbal and verbal-visual puns, review pun typology, difficulties of rendering verbal and verbal-visual puns and translation techniques, gather and distribute the examples of puns in Lithuanian-dubbed animated film Mr. Peabody & Sherman into verbal and verbal-visual puns, compare and examine the distribution of pun types and used translation techniques by providing examples and analysing them from the perspective of multimodal cohesion and dubbing synchronies, focusing on qualitative analysis rather than quantitative. The object of the research is verbal and verbal-visual puns in Lithuanian-dubbed animated film Mr. Peabody & Sherman (2014). The rendering of puns has been analysed by Lithuanian scholars mostly in fiction, e.g., Veličkienė (2019) focused on pun translation in Shakespeare’s sonnets, and Pažūsis (2017) provided an insightful analysis of pun translation in literature. However, the translation of puns in audiovisual translation (AVT) has not gained much attention from Lithuanian scholars, i.e., puns in dubbing have only been analysed by Astrauskienė (2016), and some cases of puns have been reviewed in a dissertation that focuses on humour in AVT by Šidiškytė (2017). A similar approach to pun translation has been observed in the works of foreign scholars, who tend to analyse puns only as a mechanism through which humour can be conveyed in AVT, e.g., Dore (2019), De Rosa (2014). One of the most significant analyses on puns in AVT was conducted by Schröter (2005), who focused on pun translation from English into German, Swedish, Danish and Norwegian languages in subtitled and dubbed animated films. The article written by Sanderson (2009) should be mentioned as well because it explores verbal-visual puns. However, the conducted research has not analysed verbal as well as verbal-visual puns from English into Lithuanian-dubbed animated films from the perspective of dubbing synchronies. The analysis of the research will be conducted by employing the multimodal transcription method in order to provide a comparative qualitative analysis.

1. Peculiarities of verbal and verbal-visual puns

As this research focuses on verbal and verbal-visual puns, it is essential to review these concepts in greater detail. There is no consensus among scholars on the usage of the terms pun, paronomasia and wordplay/play on words; thus, first, the differences and similarities of these terms will be clarified, providing the definition and reason for the chosen term; secondly, verbal-visual puns will be explained in greater detail; thirdly, the typologies of puns will be introduced with further elaboration on homonymy, homophony, homography and paronymy, which is the typology that has been chosen for the analysis.

There has been observed a great diversity of definitions of terms pun, paronomasia and wordplay/play on words, and it seems that different scholars as well as different dictionaries tend to use some of them as synonyms. The origin of the term pun could be traced from the Italian word puntiglio “meaning fine point, quibble” (MWD) and is defined as contrasting “linguistic structures with different meanings on the basis of their formal similarity” (Delabastita, 1996, p. 128). In contrast, the term wordplay (also referred to as play on words) is defined by Delabastita as a more general term used for “various textual phenomena in which structural features of the language(s) used are exploited in order to bring about a communicatively significant confrontation of two (or more) linguistic structures with more or less similar forms and more or less different meanings” (Delabastita, 1996, p. 128). Finally, paronomasia, which comes from Latin paronomazein and means “to call with a slight change of name” (MWD), tends to be perceived as a more elaborate term and a synonym to pun (Pažūsis, 2017, p. 59). Following the terminology of Delabastita, the term pun has been chosen in this research to refer to the cases of verbal and verbal-visual puns with the focus on contrasting meanings that could be either expressed verbally or verbally-visually, but would still convey formal similarity.

Furthermore, the concept of verbal-visual pun has to be discussed in greater detail. According to Kaźmierczak (2017), a verbal-visual pun is intersemiotic and appears when the relation between two meanings is encoded in two semiotic layers, i.e., verbal text and image. The origin of verbal-visual puns could be traced back to ancient history; e.g., Brotherston (1998) states that they could be dated back to ancient Egyptian cursive writing that, together with hieroglyphs, offered an alternative meaning in visual form. Another example of a verbal-visual pun could be the code of arms, where the person’s surname and the image of the canting arms would create a verbal-visual pun (EB). In the context of AVT, Kaźmierczak briefly defines verbal-visual puns as “highly complex multimodal messages” (Kaźmierczak, 2017, p. 144) due to the numerous translation challenges that will be discussed in the next section.

There are generally identified two typologies of puns, i.e., vertical and horizontal or homonymy, homophony, homography and paronymy. Vertical and horizontal puns can be as well referred to as implicit and explicit (Offord, 1997, p. 234). A pun is considered horizontal when both components of the pun are near one another in the text and vertical when both meanings of the pun are related to one word or a combination of words that have been mentioned only once (Pažūsis, 2017, p. 60). However, the focus of this research is on the construction of puns rather than their place. Thus, another typology of puns (homonymy, homophony, homography and paronymy) is employed in this research because it is considered universal and can occur in any language. The words that fall under these categories can be called homonyms, homophones, homographs and paronyms (Delabastita, 1993, pp. 79–81). Homonyms are words that are absolutely identical in their pronunciation and spelling, e.g., “bank” as a financial institution and “bank” as a land on the edge of the river (Schröter, 2005, p. 164). It should be noted that polysemous words have the same pronunciation and spelling; thus, they fall under the category of homonyms (Pažūsis, 2017, p. 60; Schröter, 2005, pp. 168–170). The second category of homophones refers to words with different spellings but identical pronunciations, e.g., “dye” meaning to change colour and “die” meaning cease to live (Schröter, 2005, p. 165). The third category of pun is homographs, which are words that have different pronunciations but identical spelling, e.g., “bow” meaning to bend the head and “bow” referring to a weapon for shooting arrows (Schröter, 2005, p. 166). The final category of puns is paronyms, which refer to words that have similar pronunciation or spelling, e.g., “can” meaning being able to and “cancan” referring to women’s dance of French origin (Schröter, 2005, p. 172). When comparing English and Lithuanian languages, Pažūsis states that the Lithuanian language has fewer resources to create homophony or homography-based puns but has more homonyms that are called homoforms and are based on different forms of different words that tend to be spelt and pronounced in the same way, e.g., Lithuanian words “kiškis” (a noun meaning “rabbit”) and “kiškis” (imperative mood of the verb meaning “intervene”) (Pažūsis, 2017, p. 60). These differences when creating a pun in the English and Lithuanian languages are caused by the fact that one language is analytical (English), and the other is synthetical (Lithuanian) (Pažūsis, 2017, p. 60).

To sum up, even though the use of terms pun, paronomasia and wordplay/play on words greatly differ among scholars, this research is based on Delabastita’s (1993) terminology, according to which verbal and verbal-visual puns are based on their contrasting meanings that can be expressed verbally or verbally-visually, but still have a similar linguistic form. Puns are usually categorised either into vertical and horizontal or homonyms, homophones, homographs and paronyms. However, due to the multimodal nature of the AVT, the later typology of puns has been chosen for the analysis. Further on, the translation of verbal and verbal-visual puns will be reviewed.

2. Translation of verbal and verbal-visual puns

There are many different and contradicting limitations and restrictions in a small excerpt of a text, conveying verbal or verbal-visual pun, that the choice of the translator becomes much more difficult than in the case of a “simple” translation (Delabastita, 1997). Moreover, in the case of AVT of verbal or verbal-visual puns, the translator has to take into consideration not only linguistic, but as well synchronic and multimodal limitations and can employ different translation techniques. Thus, the difficulties of rendering verbal or verbal-visual puns, as well as possible translation techniques, will be described in greater detail in this section.

First, the linguistic problems of rendering verbal and verbal-visual puns should be reviewed. The translation of puns is often named untranslatable, because even though there are equivalents of the meanings of puns in the TL, usually, these words in the TL do not share a similar form; thus, they cannot create a pun (Schröter, 2005, p. 141). The task of transferring a pun becomes even more difficult when it is based on the proper names, which have to be phonetically or graphically adapted to the norms of the TL (Pažūsis, 2017, p. 61). Thus, in such cases, the translator is limited not only be the meaning of a pun, but its form as well (Pažūsis, 2017, p. 61).

Second, the problems of rendering verbal and verbal-visual puns related to the synchronies of dubbing should be outlined. Dubbing refers to replacing the source track with a target language track trying to adhere to the time, phrases and lip movement of the original (Luyken et al. cited in Pérez-González, 2014, p. 21). Thus, rendering verbal and verbal-visual puns in dubbing becomes even more restricted because the translator has to “adapt the initial translation to the visual demands of the ST” (Chaume, 2012, p. 9). Furthermore, when adapting the initial translation of puns in dubbing, three types of dubbing synchronies should be regarded: phonetic synchrony, which refers to the adaptation of mouth movements of actors; kinesic synchrony, which adheres to the body movements and gestures of actors, and isochrony, which concerns the duration of utterances (Chaume, 2012, p. 9).

Third, the multimodal cohesion problems of transferring verbal and verbal-visual puns in dubbing should be described. The AVT texts are considered multimodal, and verbal-visual puns could even be defined as very complex multimodal messages (Kaźmierczak, 2017, p. 144). However, the shift in the research of dubbing when the scholars transferred their focus from lip synchrony to the multimodal rendering of meaning across different semiotics has been made quite recently (Pérez-González, 2009, p. 22). According to Chaume (2004), the meaning of the SL is transferred via acoustic and visual channels that have their own groups of semiotic codes, i.e., the acoustic channel includes spoken language, para-verbal and non-verbal acoustic signs, and the visual channel includes photographic, iconographic and mobility codes. Thus, the contemporary research on dubbing is more focused on the role of TT as a dynamic system (Pérez-González, 2009, p. 23), or how Kaindl simply put it: “From playing with words to playing with signs” (Kaindl cited in Kaźmierczak, 2017, p. 122). Thus, the multimodal cohesion limitations add another layer of complexity to rendering verbal and verbal-visual puns in AVT.

Furthermore, when rendering verbal or verbal-visual puns, different translation techniques can be employed by the translator. In this research, the translation techniques for rendering puns that have been created by Delabastita (1996, p. 134) will be used, as they have already been successfully applied to the translation of puns in the field of AVT. For example, Camilli (2019) adapted Delabastita’s translation techniques for the analysis of wordplay, including punoids, in dubbing British comedy series. Aljuied (2021) included Delabastita’s translation techniques as one of two typologies for the analysis of Arabic (re)dubbing of wordplay in Disney animated films, and Schauffler (2012) incorporated Delabastita’s translation techniques when creating a new typology for a receptor-oriented study on translation of wordplay in subtitling. Thus, eight translation techniques distinguished by Delabastita will be explained in greater detail below:

1. PUN→PUN, when the SL pun is translated into TL pun, regardless of structural, semantical or functional loss;

2. PUN→NON-PUN, when the SL pun is translated into TL phrase that does not contain a pun;

3. PUN→PUNOID, when the SL pun is translated into a related rhetorical device (e.g., repetition, alliteration, irony, etc.);

4. PUN→ZERO, when the SL pun is omitted in the TL;

5. PUN ST = PUN TT, when the SL pun is written in its original form and structure in the TT;

6. NON-PUN→PUN, when the ST segment has no pun, but the translator introduces a pun in the TT, possibly as a form of compensation;

7. ZERO→PUN, when there was no SL segment for reference, but the translator created a pun in the TT;

8. EDITORIAL TECHNIQUES, e.g., when the translator adds explanatory footnotes (Delabastita, 1996, p. 134).

As this research is focused on dubbing, editorial techniques will not be included in the analysis. Thus, 7 translation techniques will be used in the analysis of verbal and verbal-visual puns.

To sum up, rendering verbal and verbal-visual puns in dubbing is a highly complicated task that creates linguistic, synchronic and multimodal challenges for the translator. These difficulties can make the translation of puns nearly untranslatable. However, the translation techniques proposed by Delabastita (1996, p. 134), i.e., PUN→PUN, PUN→NON-PUN, PUN→PUNOID, PUN→ZERO, PUN ST = PUN TT, NON-PUN→PUN, ZERO→PUN, help to tackle the translator’s task.

3. Translation of verbal and verbal-visual puns in Lithuanian-dubbed animated film Mr. Peabody & Sherman

The following section focuses on the analysis of verbal and verbal-visual puns from English into Lithuanian in the animated film Mr. Peabody & Sherman (2014) which was directed by Rob Minkoff (Mr. Peabody & Sherman). This animated film revolves around a very smart dog called Mr. Peabody and his adopted human boy Sherman, who both experience various adventures and meet the most prominent historical figures while travelling through time in a time machine called Wabac. The film has gained quite a success with 16 award nominations and 2 wins, i.e., BMI Film Music Award and BTVA Feature Film Voice Acting Award for Stanley Tucci as the voice of Leonardo da Vinci (Mr. Peabody & Sherman). This animated film has been chosen for the analysis of verbal and verbal-visual puns in dubbing from English into Lithuanian language because the main character, who is portrayed as being very intelligent, tends to occasionally insert a pun in order to showcase his intellect and only when the events take an unfortunate turn, he says: “This is no time for puns! Even good ones” (Minkoff, 2014). Thus, the film contained a number of pun examples. In total, 27 cases of puns were collected and grouped according to the verbal or verbal-visual puns categories. Considering all 27 cases of puns that have been collected, 14 of them fall under verbal puns, and 13 were verbal-visual puns, which correspondingly make 52% and 48%. Thus, in order to explore this distribution and compare them, the following sub-sections will be subdivided into the analysis of pun types and translation techniques of verbal and verbal-visual puns.

3.1 Types of verbal and verbal-visual puns in Lithuanian-dubbed animated film “Mr. Peabody & Sherman”

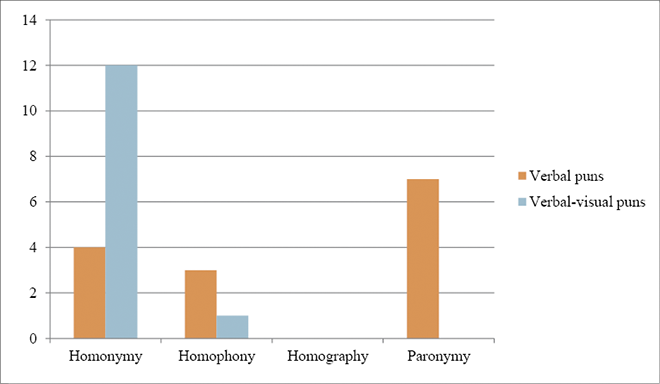

This sub-section will discuss the types of puns that have been found in this analysis of verbal and verbal-visual puns. The distribution of homonymy, homophony, homography and paronymy are illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Types of verbal and verbal-visual puns in Mr. Peabody & Sherman

Source: created by the author

As shown in Fig. 1, only three types of verbal puns have been found in the analysis, i.e., homonymic, homophonic and paronymic. No instances of homography have been found; however, it was not surprising because Schröter (2005, p. 166) has clearly indicated that the instances of homography are very rare. Furthermore, the analysis revealed that almost all instances of verbal-visual puns fall under the category of homonymy, which might be influenced by the fact that verbal-visual puns tend to be based on polysemous words, i.e., the uttered word in dubbing becomes a verbal-visual pun when its clashing meaning is shown on the screen; however, one instance of homophonic verbal-visual pun has been found. In order to clarify the differences between verbal and verbal-visual puns referring to the types of puns, some examples will be provided below.

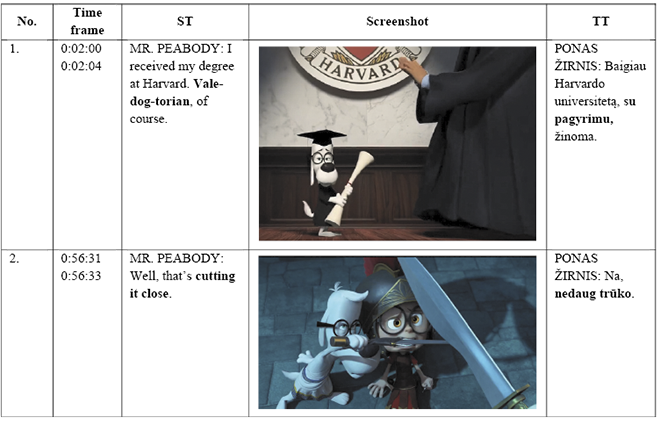

There have been found 4 instances of verbal homonymy and 12 cases of verbal-visual homonymy that are usually based on the polysemous words due to their intersemiotic construction. The examples of verbal and verbal-visual homonymy are provided in Table 1.

In the first case, the homonymic verbal pun is based on the word “booby”, which is a polysemous word; thus, having identical spelling and pronunciation but two different meanings. The first meaning refers to the whole phrase “booby trap”, which means “a bomb or mine that is set to be exploded by some action of the intended victim, as when some seemingly harmless object is lifted” (CD). The second meaning that causes Sherman’s laughter comes from slang, meaning “a female breast” (CD). In the second case, a homonymic verbal-visual pun could be observed. It is created with the phrase “barking up the wrong tree”, which is an idiom meaning following the wrong cause of action (CD), and the second clashing meaning is created through image because this phrase is told to Mr. Peabody, who is a dog; thus, the word “barking” acquires the second meaning, i.e., producing loud rough noise (CD). The examples of homonymy in verbal and verbal-visual puns clearly illustrate the differences between the two groups revealing, that in most cases, verbal-visual puns are homonymic, based on the polysemy of words where the second meaning creating a pun appears only through image, and verbal pun can be homonymic, homophonic, paronymic or in rare cases homographic. Thus, other instances of verbal and verbal-visual homophony will be illustrated.

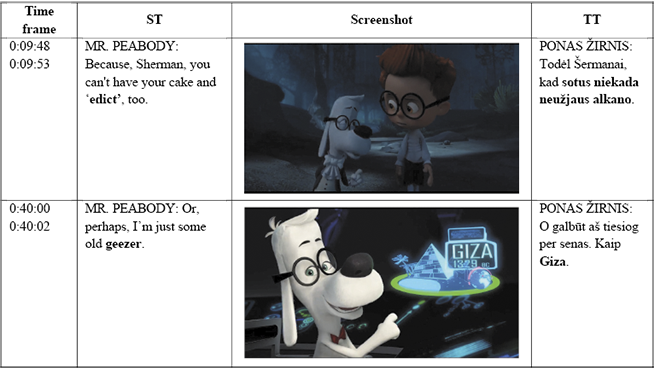

Homophonic verbal and verbal-visual puns refer to the words that have identical pronunciation, but different spelling. There has been observed 3 cases of verbal homophony and 1 case of verbal-visual homophony, both of which are presented below.

The first case illustrates an example of verbal homophony because it contains two words: “Ay”, which is the proper name of the king of Egypt (EB), and the pronoun “I”. Both of these words are actually pronounced in the same way, i.e., [aɪ], which creates a verbal pun in the SL. The second case illustrates an example of a homophonic verbal-visual pun that is based on the word “geezer”, which is a slang word for an old man, and it is pronounced as [giːzəʳ] (CD). The verbal-visual pun is created when, on screen, Mr. Peabody is pointing to the place “Giza”, referring to the ancient Egyptian city with pyramids, which is pronounced almost identically as [ɡiːzə]. Furthermore, such cases when the verbal-visual pun is based on other than homonymic puns are rare and rather difficult to find, but in this case, the visual image of the pyramid is reinforced by the intertitle “GIZA”, making it easier for the audience to notice verbal-visual pun.

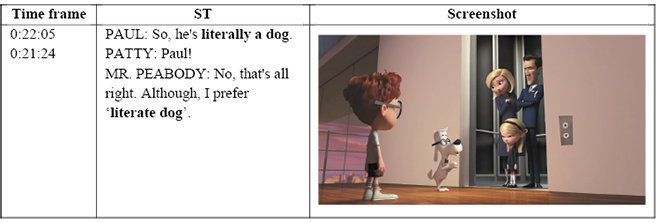

The third category of puns is paronymy, which has been found in 7 cases of verbal puns. There have not been any instances of verbal-visual paronymy found; thus, only one example of verbal paronymy is provided in Table 3.

Table 3. Types of verbal puns: paronymy

Source: created by the author

Paronyms are words that have similar spelling and pronunciation; thus, in the case presented above, the paronymic verbal pun is created with two words that have similar spelling and pronunciation but differ in meaning, i.e., “literally” and “literate”. The word “literally” is pronounced as [lɪtərəli] and means in literal meaning, exactly, whereas “literate” is pronounced as [lɪtərət] and means able to read and write.

After reviewing the types of puns in verbal and verbal-visual puns, there has been found only cases of homonymy, homophony and paronymy, but no examples of homography. Verbal puns contained various examples of homonymy, homophony and paronymy, whereas almost all cases of verbal-visual puns were homonymic, due to the fact that they were created employing polysemous words. Thus, the distribution of translation techniques for rendering verbal and verbal-visual puns will be discussed in the next subsection.

3.2 Translation techniques of verbal and verbal-visual puns in Lithuanian-dubbed animated film “Mr. Peabody & Sherman”

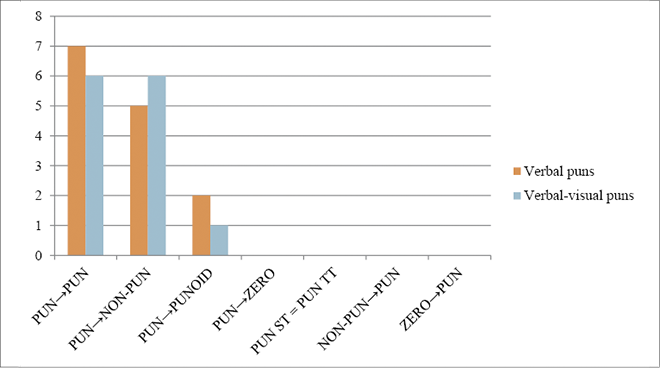

Further on, the translation techniques that have been named by Delabastita (1996, p. 134), i.e., PUN→PUN, PUN→NON-PUN, PUN→PUNOID, PUN→ZERO, PUN ST = PUN TT, NON-PUN→PUN, ZERO→PUN, will help to reveal the most common translation choices for rendering verbal and verbal-visual puns in the film. The distribution of translation techniques has been provided in the figure below.

Fig. 2. Translation techniques of verbal and verbal-visual puns in Mr. Peabody & Sherman

Source: created by the author

The analysis of the employed translation techniques revealed that all cases of verbal and verbal-visual puns in the analysis fall under 3 techniques, i.e., PUN→PUN, PUN→NON-PUN, PUN→PUNOID. There has been not found any cases of other techniques, such as PUN→ZERO, PUN ST = PUN TT, NON-PUN→PUN, ZERO→PUN. Thus, the examples of 3 types of translation techniques will be analysed below.

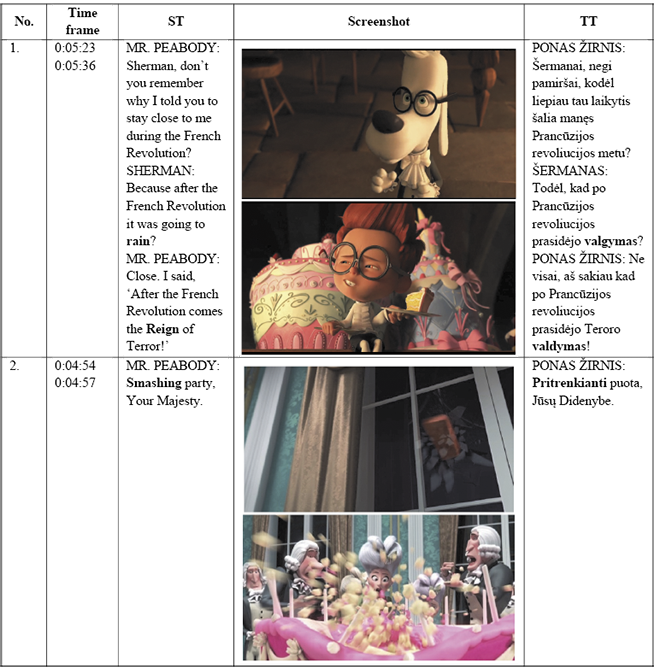

The most commonly used translation technique was PUN→PUN when the SL verbal or verbal-visual pun was replaced with a TL pun, as illustrated in the table below.

Table 4. Translation techniques of verbal and verbal-visual puns: PUN→PUN

Source: created by the author

The table provided above conveys a homophonic verbal pun in the first case that is based on the word “rain” meaning water falling in drops from the clouds, and ”reign” in the phrase “reign of terror”, which refers to the period of time between the summers of 1793 and 1794, which was considered the most violent phase of the French Revolution, but both of these words have identical pronunciation, i.e., [reɪn] (EB, MWD). The translation technique that has been employed by the translator in dubbing is PUN→PUN because the verbal pun is retained in the same place as in the original, but with different words that create paronymic pun. The word “rain” is replaced with “valgymas” (Eng. “eating”) and “reign” with the word “Valdymas” (Eng. “ruling”). It is a rather successful example of rendering verbal puns in dubbing because the linguistic obstacles have been tackled by finding words that sound similar and spell similar and retaining the meaning of the specific phrase related to the French Revolution. Moreover, the multimodal cohesion has been retained because even though “rain” and “valgymas” have different meanings, the image of the screen shot shows that Sherman is actually eating a cake; thus, it should not cause any dissociations between what is seen and heard. Furthermore, the synchronies of dubbing have been regarded as well. Both characters are speaking in such a manner that no close mouth movements can be clearly seen: Sherman is talking while eating a cake, and Mr. Peabody is talking with his nose pointed down. The kinesic synchrony and isochrony are not disrupted as the gestures of eating Sherman and Mr. Peabody, who is trying to explain with his paws slightly raised in front of him, are rather universal and the duration of the utterances are retained in such a manner that the target audience could enjoy the verbal pun in the dubbed version of the film.

The second case illustrates a homonymic verbal-visual pun that is based on the word “smashing”, the utterance of which has the meaning of impressive or very enjoyable when referring to a party, and the image of a brick flying through the window into the cake adds another meaning of loudly crushing into small pieces (CD). The translator managed to find an equivalent Lithuanian word, “pritrenkianti” (Eng. “astounding”), which conveys the same meanings in the TL, creating a corresponding homonymic pun, and as there are no close mouth or body movements shown on the screen, the example succeeds to tackle linguistic, multimodal and synchronic obstacles and transfer verbal-visual puns by employing PUN→PUN translation technique.

Another translation technique that has been found when rendering verbal and verbal-visual pun in the animated film is PUN→NON-PUN, which is explained in greater detail in the following table.

Table 5. Translation techniques of verbal and verbal-visual puns: PUN→NON-PUN

Source: created by the author

The first example provided above illustrates a paronymic verbal pun based on the word “valedictorian”, which refers to a student who has the highest grades and usually makes a speech at the graduation ceremony, but in this case, the word “dog”, which directly refers to Mr. Peabody, is inserted in the word by replacing two letters, slightly altering the pronunciation and resulting in a word “vale-dog-torian” (CD). However, in this particular case, it was very difficult to find a possible verbal pun in the TT because in Lithuania, the diploma of such student is referred to “Cum Laude” or “Magna Cum Laude”, and the word “dog” is “šuo”; thus, any attempt to insert “šuo” into the phrases, e.g., “Šuo Laude” or “Magna šuo Laude”, seems very unnatural and would hardly be understood by the target audience of the film, which is mainly composed of children. Thus, the translator decided to retain the meaning “su pagyrimu” (Eng. “with honours”), but loose the verbal pun, without any loss of multimodal cohesion or dubbing synchronies: the image corresponds to the meaning of the heard text, the mouth movements are not seen, because the audience hears the voice of Mr. Peabody from the perspective of a narrator, the body movements and duration of utterances are retained and create a coherent scene.

The second example illustrates the translation technique PUN→NON-PUN that has been used for rendering verbal-visual puns. The homonymic verbal-visual pun is based on the phrase “cutting it close”, which is an idiom meaning to almost not be able to do something, but the image where a soldier almost cut Sherman into pieces adds the second meaning of dividing into smaller parts (MWD). However, the phrase has been transferred by employing only the first meaning, which is almost not being able to do something “nedaug trūko” (Eng. “it was close”) and losing the aspect of verbal-visual pun in the TL. In this case, as the meaning is retained, the multimodal cohesion as well as lip synchrony (no close-up mouth movements), kinesic synchrony (the phrase seems suitable in the situation where a character nearly escapes death) and isochrony (the time of utterance ends as in the SL) are retained.

Finally, there have been found three cases of PUN→PUNOID for rendering verbal (2 cases) and verbal-visual (1 case) pun. Thus, two examples of PUN→PUNOID are explained below.

The first case provided in Table 6 illustrates the translation technique PUN→PUNOID, where a paronymic verbal pun is based on the words “eat it” and “edict”. In fact, the phrase “to have your cake and eat it too” is an idiom meaning to have two good things at the same time, which is impossible (CD). The verbal pun is created by replacing the word “eat” with “edict”, which refers to an official order, and the whole scene is referring to Marie Antoinette, who could not have her dessert and release an edict to distribute bread to the poor. In the TT, it is seen that the verbal pun is replaced by the Lithuanian saying “sotus niekada neužjaus alkano” (Eng. “the sated will never feel compassion towards the hungry”). Even though the verbal pun is lost, the multimodal cohesion and dubbing synchronies have been retained. In this case, the short saying might have been chosen in the TT in order to retain the isochrony because there are no particular body movements or close-up lip movements that could disrupt kinesic or lip synchronies.

Table 6. Translation techniques of verbal and verbal-visual puns: PUN→PUNOID

Source: created by the author

In the second example, the homophonic verbal-visual pun, based on the word’s “geezer” (an old person) and “Giza” (a city in ancient Egypt), is rendered by using a comparison “kaip Giza” (Eng. “like Giza”); thus, it falls under the translation technique PUN→PUNOID. The translator has decided to retain only the second meaning of the word Giza in the translation in order to keep the multimodal cohesion and kinesic synchrony because Mr. Peabody is clearly pointing (body movement) to Giza on the screen and retaining the isochrony by shortening the utterance. It should be pointed out that the lip synchrony is retained as well as there are no close mouth movements, particularly in the case of Mr. Peabody; his physical appearance and big nose usually tend to overshadow mouth movements and not cause many difficulties in rendering phonetic synchrony of this character in the film.

To sum up, the translator employed only 3 translation techniques for rendering verbal and verbal-visual puns, i.e., PUN→PUN, PUN→NON-PUN, PUN→PUNOID, out of which PUN→PUN prevailed, indicating translator’s attempt to tackle linguistic challenges of transferring verbal and verbal-visual puns as well taking into consideration the multimodal cohesion and dubbing synchronies that have been successfully retained in the analysed cases.

Conclusion

The analysis of verbal and verbal-visual puns from English into Lithuanian in the animated film Mr. Peabody & Sherman has revealed the following conclusions:

In total, there has been collected 27 cases of puns that were classified as verbal puns (14) and verbal-visual puns (13), which represent 52% and 48% of all the examples.

The categorisation of verbal and verbal-visual puns according to the types revealed that all cases fall under homonymy, homophony and paronymy, no examples of homography have been found as expected. Verbal puns contained examples of homonymy, homophony and paronymy, but the paronymic verbal puns prevailed the most. Almost all cases of verbal-visual puns were homonymic, except for one homophonic verbal-visual pun, because of their intersemiotic construction that is usually based on polysemous words.

All cases of verbal and verbal-visual puns have been rendered by employing 3 translation techniques, i.e., PUN→PUN, PUN→NON-PUN, PUN→PUNOID, and no examples of PUN→ZERO, PUN ST = PUN TT, NON-PUN→PUN, ZERO→PUN have been found. The prevailing technique for transferring verbal and verbal-visual puns was PUN→PUN, which reveals the translator’s attempt to tackle linguistic challenges as well as taking into consideration the multimodal cohesion and dubbing synchronies that have been successfully retained in the analysed cases.

This analysis of rendering verbal and verbal-visual puns from English into Lithuanian in the animated film Mr. Peabody & Sherman has shown that more extensive research including a number of Lithuanian-dubbed animated films is necessary in order to draw a more accurate conclusions on the matter of verbal and verbal-visual puns in dubbing.

Sources

Minkoff, R. (dir.), 2014. Mr. Peabody & Sherman. Motion picture. Available at: <https://www.bilibili.tv/en/video/2008472997>.

Minkoff, R. (dir.), 2014. Ponas Žirnis ir Šermanas. Motion picture. Available at: <https://www.pasakos.lt/ponas-zirnis-ir-sermanas/>.

References

Aljuied, F. M. J., 2021. The Arabic (Re)dubbing of Wordplay in Disney Animated Films. Doctoral Dissertation. London: University College London.

Astrauskienė, J., 2016. The Witty Ways Wit Works: The Translation of Puns in Dubbed Animation. Audiovisual Translation: Dubbing and Subtitling in the Central European Context, Conference Proceedings, pp. 35–46.

Brotherston, G., 1998. Script in Translation. In: M. Baker, K. Malmkjar, eds. Encyclopedia of Translation Studies. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 211–218.

Camilli, L., 2019. The dubbing of wordplay: The case of A touch of cloth. Journal of Audiovisual Translation, 2 (1), pp. 75–103. https://doi.org/10.47476/jat.v2i1.24.

Chaume, F., 2004. Synchronization in dubbing. A translational approach. In: P. Orero, ed. Topics in Audiovisual Translation. Amsterdam, Philadelphia: John Bejamins, pp. 35–52. https://doi.org/10.1075/btl.56.

Chaume, F., 2012. Audiovisual Translation: Dubbing. Manchester: St Jerome. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003161660.

CD – Collins Dictionary. Available at: <https://www.collinsdictionary.com/>.

Delabastita, D., 1993. There’s a Double Tongue: An Investigation into the Translation of Shakespeare’s Wordplay, with Special Reference to Hamlet. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

Delabastita, D., 1996. Introduction. In D. Delabastita, ed. Wordplay and Translation. Special Issue of The Translator: Studies in Intercultural Communication, 2 (2), pp. 127–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/13556509.1996.10798970.

Delabastita, D., 1997. Introduction. Essays on Punning and Translation. Manchester and Namur: St. Jerome Publishing.

De Rosa, G. L., 2014. Back to Brazil: humor and sociolinguistic variation in Rio. In: G. L. De Rosa, F.B.A. de Laurentiis, E. Perego, eds. Translating Humour in Audiovisual Texts. Bern: Peter Lang, pp. 105–128.

Dore, M., 2019. Humour in Audiovisual Translation: Theories and Applications. New York, London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003001928.

EB – Encyclopedia Britannica. Available at: <https://www.britannica.com/>.

Kaźmierczak, M., 2017. Verbal-Visual Punning in Translational Perspective. Rocznik Komparatystyczny, 8 (8), pp. 121–150. https://doi.org/10.18276/rk.2017.8-06.

MWD – Merriam Webster Dictionary. Available at: <https://www.merriam-webster.com>.

Mr. Peabody & Sherman. Available at: <https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0864835/>.

Offord, M., 1997. Mapping Shakespeare’s Puns in French Translations. In: D. Delabastita, ed. Essays on Punning and Translation. Manchester and Namur: St Jerome Publishing, pp. 233–260.

Pažūsis, L., 2017. Kaip į lietuvių kalbą verčiami angliški kalambūrai [Ways of Rendering English Puns into Lithuanian]. Vertimo studijos, 10, pp. 58–80. https://doi.org/10.15388/VertStud.2008.1.10619. [In Lithuanian].

Pérez-González, L., 2009. Audiovisual Translation. In: M. Baker, G. Saldanha, eds. Routledge Encyclopedia of Translation Studies. London and New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, pp. 13–20.

Pérez-González, L., 2014. Audiovisual Translation: Theories, Methods and Issues. Abingdon: Routledge.

Sanderson, J., 2009. Strategies for the Dubbing of Puns with One Visual Semantic Layer. In: J. Díaz Cintas, ed. New Trends in Audiovisual Translation. Bristol: Multilingual Matters, pp. 123–132. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781847691552-011.

Schauffler, S., 2012. Investigating Subtitling Strategies for the Translation of Wordplay in Wallace and Gromit - An Audience Reception Study. Doctoral Dissertation. Shefield: University of Shefield.

Schröter, T., 2005. Shun the Pun, Rescue the Rhyme? The Dubbing and Subtitling of Language-Play in Film. Doctoral Dissertation. Karlstad: Karlstad University Studies.

Šidiškytė, D., 2017. Humoro raiškos transformacijos audiovizualiniame vertime. Daktaro disertacija [The Transformations of the Expression of Humour in Audiovisual Translation. Doctoral dissertation]. Vilnius: Vilniaus universitetas. [In Lithuanian].

Veličkienė, D., 2019. Williamo Shakespeare’o sonetų vertimai į lietuvių kalbą: atitikmens problema. Daktaro disertacija [Translation of William Shakespeare’s Sonnets into Lithuanian: The Problem of Correspondence. Doctoral dissertation]. Vilnius: Mykolo Riomerio universitetas. [In Lithuanian].