Slavistica Vilnensis ISSN 2351-6895 eISSN 2424-6115

2020, vol. 65(1), pp. 59–71 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/SlavViln.2020.65(1).36

Semantics of Lithuanian Baltas and Polish Biały: An Attempt at a Contrastive Analysis

Viktorija Ušinskienė

Vilnius University, Lithuania

e-mail: viktorija.usinskiene@flf.vu.lt

ORCID: 0000-0001-9070-8659

Abstract. The paper presents the results of a contrastive semantic analysis of the Polish lexeme biały ‘white’ and its Lithuanian equivalent baltas. The research aimed at comparing the collocability of Pol. biały / Lith. baltas with names of various objects and phenomena (both in the literal and figurative senses) including the identification of the prototype references and connotative meanings. The analysis has illustrated that Pol. biały / Lith. baltas have similar ranges of use and develop almost identical connotations. In both languages, whiteness is interpreted as the lightest color whose qualitative prototype pattern is SNOW (cf.: Pol. biały jak śnieg — Lith. baltas kaip sniegas), and the quantitative prototype pattern is DAYLIGHT (cf. Pol. biały dzień — Lith. balta diena). The prototype references create characteristic connotation chains: ‘as white as snow’ — ‘pure (also morally)’ — ‘innocent’ — ‘honest’ — ‘good’; ‘as white (light) as daylight’ — ‘transparent’ — ‘obvious’ — ‘legal’ — ‘good’. The differences between the discussed units are mainly noted on the level of the lexical components with individual connotations. Apart from the few phenomena that are culturally specific (e.g. Pol. białe małżeństwo ‘a marriage without intimacy’), in the use of the lexemes biały / baltas there are no major discrepancies. Instead, it is possible to note only the asymmetry as it is in the case with the related meanings ‘clarity’ and ‘legality’ where the former has more examples in Polish, while the latter is found only in Lithuanian.

Keywords: color terms, semantics of color, white color, contrastive analysis.

Liet. baltas ir lenk. biały: gretinamosios semantinės analizės bandymas

Santrauka. Straipsnyje pateikiami lenkų kalbos leksemos biały ir jos lietuviško atitikmens baltas kontrastyvinės semantinės analizės rezultatai. Analizė pagrįsta Tokarskio [1995] ir Waszakowos [2000a, 2000b] metodologija, kuria vadovaujantis siekiama palyginti baltumo pavadinimų derinimą su skirtingais objektais, nurodant prototipines referencijas. Atlikti tyrimai rodo, kad lenk. biały ir liet. baltas yra panašiai vartojami ir turi beveik identiškas konotacijas. Abiejose kalbose balta spalva interpretuojama kaip šviesiausia, kurios kvalitatyviniu prototipu galima teigti esant sniegą (por. biały jak śnieg — baltas kaip sniegas), kvantitatyviniu — dienos šviesą (por. biały dzień — balta diena). Prototipiniai pavyzdžiai sudaro būdingas konotacines grandines: ‘baltas kaip sniegas — ‘švarus (taip pat morališkai)’— ‘nekaltas’ — ‘sąžiningas, doras’ — ‘geras’; ‘baltas kaip dienos šviesa’ — ‘šviesus’ — ‘aiškus / tyras’ — ‘legalus’ — ‘geras’. Atsižvelgiant į tai galima teigti, kad konotacija ‘geras’ gali būti laikoma abiejų prototipų referencija. Svarbus semantinis komponentas konotaciniu lygmeniu yra leksemų biały / baltas antonimiškumo ryšys su būdvardžiais czarny / juodas (por. ‘juodas’ / ‘tamsus’— ‘purvinas’ — ‘nemoralus’ — ‘nelegalus’ — ‘negeras’). Skirtumas tarp lenk. biały ir liet. baltas atskleidžiamas atskirų leksinių konotacijų lygmeniu, pavyzdžiui, lenkų kalbos frazeologizmas załatwić coś w białych rękawiczkach (lit. atlikti, sutvarkyti ką nors taktiškai, doriai) neturi pažodinio lietuviško atitikmens, tačiau yra būdingos abiem kalboms reikšmės ‘sąžiningumas, dorumas’ komponentas.

Reikšminiai žodžiai: spalvų pavadinimai, spalvos semantika, balta spalva, kontrastyvinė analizė.

Semantyka lit. baltas i pol. biały: próba analizy konfrontatywnej

Abstrakt. W artykule są przedstawione wyniki kontrastywnej analizy semantycznej polskiego leksemu biały i jego litewskiego odpowiednika baltas. Analiza oparta na metodologii Tokarskiego [1995] oraz Waszakowej [2000a, 2000b] miała na celu porównanie typowych dla obu języków połączeń nazw bieli z klasami różnych obiektów, w tym — ustalenie referencji prototypowych. Przeprowadzone badania ujawniły, że pol. biały i lit. baltas mają podobne zakresy użycia oraz rozwijają niemal identyczne konotacje. W obu językach biel interpretowana jest jako barwa najjaśniejsza, której kwalitatywnym wzorcem prototypowym może być śnieg (por. biały jak śnieg — baltas kaip sniegas), kwantytatywnym zaś — światło dzienne (por. biały dzień — balta diena). Odniesienia prototypowe tworzą charakterystyczne łańcuchy konotacyjne: ‘biały jak śnieg’ — ‘czysty (też moralnie)’— ‘niewinny’ — ‘uczciwy’ — ‘dobry’; ‘biały jak światło dzienne’ — ‘jasny’ — ‘jawny’ — ‘legalny’ — ‘dobry’. Wynika z tego, że konotacja ‘dobry’ może być uznana za pochodną obu referencji prototypowych. Istotnym składnikiem semantyki leksemów biały / baltas są relacje antonimiczności z przymiotnikami czarny / juodas, ujawniające się także na poziomie konotacji (por. ‘czarny’ / ‘ciemny’— ‘brudny’ — ‘niemoralny’ — ‘nielegalny’ — ‘niedobry’). Różnice pomiędzy pol. biały i lit. baltas ujawniają się głównie na poziomie wykładników leksykalnych poszczególnych konotacji, np. polski frazeologizm załatwić coś w białych rękawiczkach nie ma dosłownego odpowiednika litewskiego, ale jest wykładnikiem wspólnego dla obu języków znaczenia ‘uczciwość, dyskretność’.

Słowa kluczowe: nazwy barw, semantyka koloru, biały kolor, analiza konfrontatywna.

Received: 25/5/2020. Accepted: 12/6/2020

Copyright © 2020 Viktorija Ušinskienė. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

1. Introduction

The human perception of colors is conditioned not only biologically, but also culturally: in a number of cultures, the process of linguistic categorization of colors can acquire a distinctive character, which makes a contrastive research in the field of color naming a topical issue [Tokarski 1995; Wierzbicka 1999]. Within the scope of the present article, the results of the contrastive semantic analysis of the Polish lexeme biały ‘white’ and its Lithuanian equivalent baltas are presented. The research that is based on Tokarski’s [1995] and Waszakowa’s [Waszakowa 2000a, 2000b]1 methodologies aimed at comparing the collocability of Pol. biały and Lith. baltas with names of various objects and phenomena (both in the literal and figurative senses) including the identification of the prototype references and connotative meanings. The article deals with various types of word expressions including the fixed ones, i.e. phraseological units. In addition to the material collected from the dictionaries, the analysis has utilized the data from the Corpora of the Polish and Lithuanian languages.

2. Biały / baltas as a basic color term

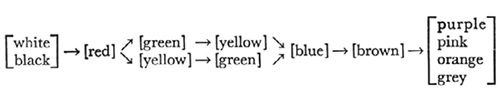

The Polish adjective biały and Lithuanian baltas correspond to the linguistic criteria typical of the basic color terms that were formulated in Berlin and Kay’s work [1969, 5–7]. According to these authors, the basic color terms are the monolexemic color names applicable to a wide class of objects, are not semantically subordinated to the names of other colors, and are synchronously unmotivated. They belong to the scope of the basic vocabulary, and are psychologically salient, which means that the language users can easily identify the color names with their corresponding prototype patterns. The names of the basic color terms are distinguished according to the above-mentioned criteria that form an evolutionary ordering in which each term has an exact position, as illustrated in the following diagram [cf. Berlin, Kay 1969, 7]:

The terms used to denote white and black colors belong to the earliest coded color names, and are characterized as the most significant in Berlin and Kay’s model. Berlin and Kay [1969, 2] discovered that all of the nearly one hundred languages they had studied had names for white and black, which resulted in the spread of the belief that they had the status of a lexical universal [Wierzbicka 1999, 434].

3. Quantitative and qualitative meanings

As it is seen from the reviews of the lexicographic entries, the lexemes biały and baltas are defined in a similar way. In both languages, the names of whiteness are referred to as ‘very light, very fair, the lightest’: Pol. najjaśniejszy, mający barwę właściwą śniegowi, mleku [MSJP, NSJP, Sz] — Lith. labai šviesus, kone sniego, pieno spalvos [LKŽe], kuris sniego spalvos [DLKŽe]. The quoted definitions reflect two basic aspects of the meaning of the terms biały and baltas that is quantitative and qualitative understanding of the color names. This distinction with the reference to the color names was introduced by Tokarski [1995, 41]; previously it was used only in natural sciences and in the history of art. Quantitative characteristics include the degree of the color lightness (intensity), while qualitative ones refer to its chromatic property.

3.1. Quantitative prototype

In both Polish and Lithuanian languages, the quantitative interpretation of WHITENESS as ‘the lightest color’ is reflected among others in the descriptions of the early time of the day: Pol. biały świt, biała zorza ‘white dawn, white sunrise’, w biały dzień ‘in broad daylight’ [Sz, SFJP] — Lith. balta aušra ‘white sunrise’, baltą dieną ‘in broad daylight’ [LKŽe]. The component biały dzień can mean ‘the dawn, the beginning of the day’, as well as ‘the noon when it is completely light outside’, cf.: Pol. Przecież jest biały dzień! ‘It’s daylight!’/ Widno się zrobiło jak w biały dzień ‘It was light as in broad daylight’ [NKJPe] — Lith. [...] Kuomet tu mane baltą dieną savuoju galėsi pavadinti? ‘When will you tell me in broad daylight that I am your betrothed?’ [LKFŽ, 146].

It should be noted, however, that the compatibility of the Lithuanian lexeme baltas with the terms of the time of the day finds fewer textual examples than its Polish equivalent, and, for instance, the praseological unit vidury baltos dienos ‘in broad daylight’ is considered a loan translation of the Russian construction среди бела дня [http://www.vlkk.lt/konsultacijos/9088-vidury-baltos-dienos].

Moreover, in both languages there are lexicalized names for white nights: Pol. białe noce — Lith. baltoji naktis; as well as for the stars shining bright: Pol. białe gwiazdy — Lith. baltosios žvaigždės, Pol. biały karzeł — Lith. baltoji nykštukė ‘white dwarf’ [DLKŽe, LKŽe]. Both, biały and baltas are used to refer to some other light phenomena, e.g. starlight, moonlight, sun, fire and lightning, e.g.: Pol. białe światło — Lith. balta šviesa ‘white light’/ Pol. niebo prawie białe od słońca ‘the sky is white from the sun light’; Halo wokół Księżyca ma najczęściej postać świetlnego, białego pierścienia ‘The halo around the moon usually has the form of a luminous white ring’ — Lith. […] jei Saulė leidžiasi balta, rytojaus dieną lis ‘if the sun is white at sunset, it will rain tomorrow’; Pilnas Mėnulis atrodo itin ryškus, o jo skleidžiama balta šviesa netgi akina dangaus stebėtojus ‘The full Moon looks extremely bright, and the white light it emits even dazzles sky watchers’ [NKJPe, LKŽe, DLKTE ].

The degree of lightness also determines the meaning of the expressions common to both languages in which the part biały and baltas does not mean that the object is of a white color, but rather that it is lighter than other darker objects: Pol. białe mięso, biały chleb, białe wino, biała kawa, biały pieprz — Lith. balta miesa, balta duona, baltasis vynas, balta kava, baltieji pipirai ‘white meat, white bread, white wine, “whiteˮ coffee (with milk), white pepper’ etc.

The quoted examples of the lexemes biały — baltas and their use in the meaning ‘light, fair, the lightest’ make is possible to conclude that in both languages from the quantitative aspect the prototype of the white color can be considered as DAYLIGHT [cf. Tokarski 1995, 41; Teodorowicz-Hellman 1997, 35; Waszakowa 2000a, 23]2.

The relation of the names of whiteness to light/ glow/ brightness is confirmed by the etymological data. Both Pol. biały and Lith. baltas are continuants of the pre-Indo-European root *bhel-/*bhol- ‘shiny, luminous, bright’ [cf. Old Norse bāl ‘fire’, Sanskrit bhāla ‘glow’ etc. — Boryś 2005, 26].

3.2. Qualitative prototype

A qualitative understanding of the adjectives biały and baltas implies that they function in the meaning of ‘having a white color (not red, green, etc.)’. From this point of view, both dictionary definitions and the corpus data confirm the status of SNOW as a prototype pattern for whiteness in both languages (to be exact, there are a significant number of examples coming from the texts where biały/baltas are associated with the name of snow) [cf. Tokarski 1995, 42; 2004, 49], e.g.: Pol. biały jak śnieg — Lith. baltas kaip sniegas, kaip apsnigtas ‘white as snow’ / Pol. biały od śniegu, pobielony śniegiem — Lith. baltas nuo sniego, ‘white from snow’ / Pol. białość (biel) śniegu — Lith. sniego baltumas ‘whiteness of snow’ / Pol. Śnieg ubielił dachy ‘The roofs turned white from snow’ — Lith. Miestas pabalo nuo sniego ‘The city turned white from snow’ [NKJPe, LKŽe].

In both languages, the white color of the snow is also referred to in numerous metonymic and metaphorical expressions, e.g.: Pol. biały pejzaż — Lith. baltas kraštovaizdis ‘white landscape’; Pol. biała miękkość / biały puch z nieba / biała pokrywa / biała pierzyna ‘white fluff, featherbed (about snow)’ — Lith. sniegas lyg baltas pukas / baltas sniego patalas ‘the same’; Pol. biała śmierć — Lith. baltoji mirtis ‘snow avalanches threatening with death’ [WSF, NKJPe, DLKTe ]. The exception is Polish metaphors białe szaleństwo ‘skiing’ and biała stopa ‘traces of animals on the snow’ [SFJP] which have no equivalents in Lithuanian.

From the qualitative aspect, other patterns of the white color are found in Polish and Lithuanian phraseology where the color is a component of a comparison: Pol. biały jak mleko / kreda / papier / płótno / alabaster / marmur [MSJP, Sz, WSF] — baltas kaip (lyg) pienas / kreida / popierius / drobė / alebastras / marmuras / [LKŽe; DLKTe] ‘as white as milk / chalk / paper / canvas / alabaster / marble’, etc. There are, however, some differences, e.g. a widely used and characteristic of the Polish language comparison with white lilies can hardly be found in Lithuanian texts. Nevertheless, none of these patterns have as many textual examples as SNOW, and none of them create fixed connotations.

3.3. Biały and baltas relation to the names of artifacts and natural objects

The color names biały and baltas refer to a number of object classes, and are characterized by a wide range of connectivity with the names of artifacts which include the categories such as: furniture: Pol. biały stół — Lith. baltas stalas ‘white table’; means of transport: Pol. biały statek — Lith. baltas laivas ‘white ship’; buildings and their parts: Pol. biały dom — Lith. baltas namas ‘white house’; textiles and clothing: Pol. biały obrus — Lith. balta staltiesė ‘white tablecloth’.

In addition to the above-mentioned word expressions in which whiteness is not a permanent attribute, there are examples where whiteness can be a typical feature. These include such names of artifacts, as Pol. białe płótno [SFJP I, 98] — Lith. balta drobė ‘white canvas’ [LKŽe]; Pol. białe figury [SFJP I, 99] — Lith. baltosios figūros ‘white (chess) pieces’ [DLKŽe]; Pol. biały ser [ISJP I, 91] — Lith. baltas sūris ‘white cheese’ [DLKŽe]; Pol. biała flaga [SMITK 96] — Lith. balta vėliava ‘white flag’ and others. The metaphorical description of drugs Pol. biała śmierć — Lith. baltoji mirtis ‘white death’ is also common to both languages. This phrase has one more common metaphorical meaning ‘sugar’, sometimes it is also ‘salt’ [WSF].

The differences in the metaphorical use of the terms biały — baltas are few. Some of them refer to the white color of textiles and clothes, e.g. there is no Lithuanian equivalent for the Polish expression biały tydzień [WSF] that means ‘the week after receiving the first communion’ (recently also ‘the sale of bed linen’); in its turn in Lithuanian there is a phraseological unit balta diena that means ‘a holiday when everyone is dressed in white’. In Polish, there are also some word expressions motivated by the white color and its relation to the health care professionals, such as biała niedziela ‘it is Sunday when doctors examine people who have difficulty to access the health care facilities’ [WSF], and biały marsz ‘health care professionals’ protest march’ [SF].

Both in Polish and Lithuanian, there is an expression Pol. czarno na białym — Lith. juodu ant balto [WFS, LKŽe] whose meaning is ‘in black and white’ (it is ‘in printed or written form’) that is also used in the abstract sense ‘in an obvious, uncontestable way’.

3.4. Description of human appearance

The lexemes biały and baltas are used to describe human appearance, as well as the color of the teeth, complexion, some shades of fair or gray hair, eyebrows and eyelashes: Pol. białe zęby — Lith. balti dantys ‘white teeth’, Pol. biały uśmiech — Lith. balta šypsena ‘white smile’, Pol. białe ręce — Lith. baltos rankos ‘white hands’, Pol. białe włosy — Lith. balti plaukai ‘white hair’ [Sk, Sz; LKŽe]. Cf. other expressions found in the Corpora: Pol. białowłosi starcy ‘white-haired old people’ / Wiek pobielił mu włosy ‘His hair turned white with age’ / Czarna sukienka kontrastowała z bielą jej skóry ‘Her black dress contrasted with the whiteness of her skin’ — Lith. Jo galvelė baltut baltutėlė ‘His head is white, very white’/ Jos veidelis toks baltickas kaip sniegas ‘Her face is as white as snow’ / Ji tokia balta, graži, kaip iš pieno ištraukta ‘She is so white and beautiful, as if she bathed in milk’ [NKJPe, DLKTE ].

As connected with human appearance, anatomical and medical expressions motivated by the white color of the body parts should be mentioned: Pol. białe krwinki [ISJP I, 91] — Lith. baltieji kraujo kūneliai [LKŽe] ‘white blood cells’; Pol. biała substancja mózgu [SFJP I, 99] — Lith. baltoji medžiaga ʻwhite matter of the brainʼ [TBe].

Another group of words connected with the adjectives biały and baltas(is) is the expressions describing the skin color that determines the racial belonging of a human being. The dictionaries note the following terms: Pol. biały — Lith. baltasis ‘a person belonging to white race’; Pol. rasa biała — Lith. baltoji rasė ‘white race’, Pol. biała odmiana człowieka, ludność biała — Lith. baltieji (žmonės) ‘white people’ [Sz, NKJPe, LKŽe]. There are a number of other expressions found in the Corpora that exemplify the stated meaning: Pol. białi Amerykanie — Lith. baltieji amerikiečiai ‘white Americans’, Pol. „biała” Afryka — Lith. baltoji Afrika ‘white Africans’ and some other [NKJPe, DLKTe]. This meaning is also associated with an occasional phrase Pol. biała niewolnica — Lith. baltoji vergė ‘white slave’ (about women sent abroad and forced into prostitution) [NKJPe, DLKTe] and the expressive Polish phraseme biały murzyn ‘a person exploited and treated like a slave’ [Sz].

3.5. Descriptions of psychophysiological states

In both languages there are expressions describing changes in skin color which are symptoms of certain psychophysical conditions. In this case, skin whiteness is not a positive feature, it rather signals some weakness or a disease (as contrasted to red, that is the color of health): Pol. biały (blady) jak ściana / jak papier / jak płótno — Lith. baltas (išbalęs) kaip popierėlis/ kaip drobė ‘as white (pale) as the wall / paper / canvas’, etc. [Sz, NKJPe, DLKTe].

It was noted that the change of the skin color to white is also connected with certain emotional states, such as fear, nervousness, excitation and rage, cf.: [...] jego biała, naprężona twarz nie zdradzała żadnego zaskoczenia ‘[...] his white, strained face showed no astonishment’ / Oleńka z rumianej zrobiła się w jednej chwili biała jak kreda ‘In a moment Olenka’s face went from ruddy to white as chalk’ / Szyszko był biały jak ściana ‘Szyszko was white as a wall’ [NKJPe]. However, the Polish examples of this kind are not so numerous due to the use of the hyponym blady ‘pale’ in similar contexts.

In the Lithuanian language, this meaning is expressed by the verbs išbalti, pabalti ‘to become white, pale’ (particularly by the participle forms of these verbs: išbalęs, pabalęs ‘paly, bloodless, ashy’) derived from the adjective baltas: Išbalęs veidas, matyt, nesveikuoja ‘His pale face seems to be unhealthy’ / Jam akys pabalna, kai supyksta ‘His eyes turn white when he’s angry’ [LKŽe] / Iš baimės jis net pabalo ‘He turned white with fear’ [DLKŽe].

The analyzed lexemes are also used in the metaphorical descriptions of the fit of anger, rage and fury — in Polish these are the expressions doprowadzać kogoś do białej gorączki / dostawać białej gorączki / rozpalać kogoś do białości ‘to make someone very angry, enraged, furious’ (literally: ‘to lead to a state of “white feverˮ, meaning delirium tremens’) [WSF]. In Lithuanian, the expression that has a similar meaning is iki balto kaulo (literally: ‘to the white bones’): […] jis man daėdė šiandien iki balto kaulo ‘Today he has made me furious’ [FŽ 286].

4. Extended meaning of the prototypes

4.1. The connotation ‘purity’

Tokarski [1995, 1997] states that color names can develop the connotations appropriate to its prototype reference. Тhe examples of this development in relation to qualitative whiteness are found both in Polish and Lithuanian. In the two languages, whiteness of the snow is associated with its purity and cleanness. The conceptual relation between whiteness and purity is reflected in both stereotypical and occasional word expressions, e.g. Pol.: Coś lśni białością (czystością) ‘Something shines whiteness (purity)’/ Nieskazitelnie biały obrus ‘A spotless white tablecloth’ / Masz wszystko wyczyścić do białości! ‘You have to clean everything up to whiteness!’ [Sz, NKJPe] — Lith. Numazgok stalą, kad būtų baltas! ‘Clean the table up to whiteness!’ / Baltas kaip iš pirties ‘White (clean) as after a bath’ / Baltutėliai marškiniai ‘A spotless white shirt’ [LKŽe, DLKŽe].

In both languages, the aspect of physical purity is metaphorically transferred to the sphere of moral purity, thus, developing the meaning of ‘chastity’ that is seen in the following expressions with Pol. biały and Lith. baltas: Pol. Święta dziewczyno, biała gołębico [...] ‘Тhe Holy virgin, a white dove […]’ / Twarz biała, niemal anielska, niewinna ‘Нer face is white and innocent, like an angel’s’ [Sz, NKJPe] — Lit. Toli mano mergužėlė, graži, balta lelijėlė ‘Мy girl is like a beautiful white lily and she is far away’ [LKŽe].

Moral purity is also associated with the Polish expressions with the component w białych rękawiczkach ‘in white gloves’ (to have a sense of decency), e.g. Oszustwa odbywają się tu w białych rękawiczkach ‘Cheating takes place here “in white glovesˮ ’ [WSF] which have no literal equivalents in Lithuanian. The Polish expression białe małżeństwo ‘white marriage’, which describes a situation in which the couple does not have any sexual relationship, is not found in Lithuanian either. In Polish, the figurative meaning of the verb wybielać ‘to whitewash, defend against charge, justify’ and its derivatives belong to the same semantic sphere: Adwokat usiłował wybielić oskarżonego ‘The lawyer tried to whitewash the accused’ [MSJP].

4.2. The connotations ‘clarity’, ‘legality’

By pointing to light and day as a prototype reference for whiteness, Wierzbicka underlines the significant conceptual relationship between day, clarity and vision [Wierzbicka 1999, 420]. A day in the meaning of ‘the light time of the day’ evokes positive associations in the opposition jasny ‘light’ — ciemny ‘dark’. Light is in its turn associated with good visibility, and is metaphorically transferred into the realm of positive values — ‘clarity’ and ‘legality’, while darkness connotes ‘crime’, ‘illegality’, e.g. ciemna sprawa, ciemne interesy ‘suspicious (fishy, shady) business, interests’ [Sz]. The white color takes over the connotations characteristic of clarity and then of transparency and legality.

The connotation of whiteness as ‘clarity’ is also present in the phrase w biały dzień — baltą dieną that is used in the sense ‘openly, transparently, without hiding anything’ but also ‘barefacedly’, cf.: Pol. To jest po prostu rozbój w biały dzień! — Lith. Tai tiesiog plėšikavimas vidury baltos dienos! ‘It’s a robbery happening in broad daylight!’; Pol. To przecież oszustwo w biały dzień! — Lith. Tai sukčiavimas vidury baltos dienos / pačioje dienos šviesoje! ‘This is a scam in broad daylight!’ [NKJPe, DLKTe].

It is interesting to share that in both Polish and Lithuanian, there is a noticeable semantic asymmetry in the pair Pol. biały/ Lith. baltas ‘white’ — Pol. czarny / Lith. juodas ‘black’ when it comes to the ‘legal’ — ‘illegal’ connotation. In both languages, the adjective Pol. czarny — Lith. juodas can be used in the sense of ‘illegal, illegitimate’ especially in relation to work, employment (cf. Pol. czarny rynek — Lith. juodoji rinka ‘black market’). However, there are no examples of the ‘legal’ connotation for biały in Polish. In its turn in Lithuanian, the only example of this connotation for baltas is the expression baltoji buhalterija ‘white (legal) accounting’ which has appeared in recent years as an opposition to juodoji buhalterija ‘black (illegal) accounting’.

4.3. The connotation ‘good’

The evaluation ‘good’ — ‘bad’ often takes the form of the opposition biały / baltas ‘white’ — czarny / juodas ‘black’ [Tokarski 1995, 47]. On the connotational level, it is found in the Polish/ Lithuanian phraseologisms: Pol. biała magia / Lith. baltoji magija — Pol. czarna magia / Lith. juodoji magija ‘white (good) magic — black (bad, evil) magic’ / Pol. wiedzieć, co czarne, a co białe — Lith. žinoti, kas juoda, o kas balta ‘to know the difference between good (“whiteˮ) and bad (“blackˮ)’ / Pol. robić z czarnego białe — Lith. iš juodo padaryti baltą ‘to present bad (“blackˮ) as good (“whiteˮ), to cheat someone, misrepresent facts’, cf.: Pol. Kłamiesz! Robisz z czarnego białe i z białego czarne! ‘You’re lying! You present bad (“blackˮ) as good (“whiteˮ) and vice versa’ — Lith. Iš dviejų juodų nepadarysi nė vieno balto ‘Even two bad (“blackˮ) ones can’t be turned into one good (“whiteˮ) one’ [NKJPe, LKŽe].

The opposition biały/ baltas ‘white’ — czarny/ juodas ‘black’ has developed one more metaphorical meaning: ‘using simplified assessments, evaluation, dividing phenomena into good and bad or evil without recognizing the in-between steps’: Pol. Życie to nie tylko czerń czy biel — Lith. Gyvenimas nebūna tik juodas ar baltas ‘Life is not just black or white’; Pol. Postrzegasz wszystko w czerni i bieli — Lith. Tu viską matai tik juoda ir balta spalvomis ‘You see things in black and white’ [NKJPe, LKŽe].

Tokarski relates the ‘good’ connotation for Pol. biały ‘white’ to the prototype reference SNOW by stating at the same time that the ‘bad’ connotation is more emphasized for Pol. czarny ‘black’ due to the prototype NIGHT (darkness), which in its turn is a reference point for black in both quantitative and qualitative aspects. It seems, however, that the ‘good’ connotation can be associated not only with the purity of the snow, but also with the daytime, light and brightness, which imply positive by their nature phenomena, among others there is ‘transparency’ / ‘legality’ [cf. Wierzbicka 1999, 420].

The analysis of the connotative meanings including such semantic components as the ‘good’ and the ‘clarity / legality’ (not taken into account by Tokarski) indicates that DAYLIGHT as a quantitative prototype of WHITENESS could as well as SNOW (its qualitative prototype) contribute to the development of the positive connotations of the white color in Polish and Lithuanian. Both prototype patterns could create their own connotation chains with partly overlapping meanings though:

• ‘snow’ — ‘purity’ — ‘moral purity / innocence’ — ‘good’;

• ‘daylight’ — ‘transparency’ — ‘clarity’ / ‘legality’ — ‘good’.

4.4. The connotations ‘unknown’, ‘non-existent’

The lexemes biały and baltas can also function in the meaning of ‘unknown’. E.g. the phraseological unit Pol. biała plama — Lith. balta dėmė that means ‘an unknown place on the map’ and ‘unknown facts’: Pol. Wypełniona została biała plama w lokalnej historiografii ‘A “white spotˮ in local historiography was filled’ [SFJP] — Lith. Balta dėmė geografiniame žemėlapyje ‘A “white spotˮ on the geographical map’ [LKŽe].

4.5. The connotation ‘conservative’

The white names are used, like most primary colors, in political contexts. In addition to the symbolism of the white flag (Pol. biała flaga — Lith. balta vėliava) that is a sign of ceasefire or surrender, the white color (in opposition to the red color) is also the color of monarchists and conservatives. In Poland, during the January Uprising (1863), the Whites were the supporters of the conservative party and the opponents of the democratic Reds [SMITK, 95]. Both in Lithuanian and Polish, these substantivized adjectives mean a person with conservative beliefs mainly in relation to the revolution in the USSR. The following expressions refer to the sphere associated with the Whites during the Civil War in Russia: Pol. biała gwardia — Lith. baltoji gvardija ‘the White Guard’; Pol. białogwardzista — Lith. baltagvardietis ‘a White Guardist’, Pol. biała armia rosyjska — Lith. baltoji armija ‘the White Army’; Pol. biała emigracja — Lith. baltoji emigracija ‘White emigration’.

5. Conclusion

The research has illustrated that Pol. biały and Lith. baltas have similar ranges of use and develop almost identical connotations. In both languages, whiteness is interpreted as the lightest color whose qualitative prototype pattern is SNOW (cf.: Pol. biały jak śnieg — Lith. baltas kaip sniegas), and the quantitative prototype pattern is DAYLIGHT (cf. Pol. biały dzień, biały płomień — Lith. balta diena, balta ugnis).

The prototype references create characteristic connotation chains:

• ‘as white as snow’ — ‘pure (also morally)’ — ‘innocent’ — ‘honest’ — ‘good’;

• ‘as white (light, bright) as daylight’ — ‘transparent’ — ‘obvious’ — ‘legal’ — ‘good’.

It follows therefrom that the ‘good’ connotation can be considered a derivative of both prototype references.

An important semantic feature of the lexemes Pol. biały / Lith. baltas ‘white’ is their antonymous relations with the adjectives Pol. czarny / Lith. juodas ‘black’ that also appear on the connotational level (cf. ‘black’ / ‘dark’ — ‘dirty’ — ‘immoral’ — ‘illegal’ — ‘bad’).

In addition to the meanings derived from the prototypes, both Pol. biały and Lith. baltas carry the connotations ‘unknown’, ‘non-existent’ and ‘conservative’. The two lexemes are also used in the descriptions of human beings’ appearance and their psychophysical states. However, the Polish examples of psychophysiological states are not so numerous as Lithuanian due to the use of the hyponym blady ‘pale’ in similar contexts.

The differences between the discussed units are mainly noted on the level of the lexical components with individual connotations. For instance, the Polish phraseologism załatwić coś w białych rękawiczkach ‘to do the job, tasks legally, discreetly’ has no literal equivalent in Lithuanian (Lith. atlikti, sutvarkyti ką nors taktiškai, doriai), however, there is a component in both languages carrying the common meaning ‘honesty, moral purity’.

Apart from the few phenomena that are culturally specific (e.g. Pol. białe małżeństwo ‘a marriage without intimacy’), in the use of the lexemes biały / baltas in the sphere of their connotations, there are no major discrepancies. Instead, it is possible to note only the asymmetry as it is in the case with the related meanings ‘clarity’ and ‘legality’ where the former has more examples in Polish, while the latter is found only in Lithuanian.

A significant number of the analyzed word expressions are free and occasional. However, the contextual use of the words in other word expressions is not occasional, instead it is fixed by the specific connotations of their components. It proves the productivity and the semantic potential of the analyzed color names.

Dictionaries

Boryś — W. Boryś. Słownik etymologiczny języka polskiego. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie, 2005.

DLKTe — Dabartinės lietuvių kalbos tekstynas. Prieiga per internetą: http://tekstynas.vdu.lt/tekstynas/ [2020–04–15].

DLKŽe — Dabartinės lietuvių kalbos žodynas, red. S. Keinys. T. I–VI. Prieiga per internetą: http://lkiis.lki.lt/dabartinis/ [2020–04–15].

FŽ — J. Paulauskas. Frazeologijos žodynas. Vilnius: Lietuvių kalbos institutas, 2001.

ISJP — Inny słownik języka polskiego PWN, red. M. Bańko. T. I–II. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, 2000.

LKIISe — Lietuvių kalbos išteklių informacinė sistema. Frazeologizmai. Prieiga per internetą: http://lkiis.lki.lt/frazeologizmu [2020–04–15].

LKŽe — Lietuvių kalbos žodynas, red. G. Naktinienė. T. I–XX. Prieiga per internetą: http://www.lkz.lt/ [2020–04–15].

MSJP — Mały słownik języka polskiego, red. S. Skorupka, H. Auderska, Z. Łempicka. Warszawa: PWN, 1974.

NKJPe — Narodowy Korpus Języka Polskiego, red. M. Bańko i in.: http://nkjp.pl/ [2020–04–15].

NSJP — Nowy słownik języka polskiego, red. E. Sobol. Warszawa: PWN, 2003.

SF — M. Dobrowolski. Słownik frazeologiczny, Katowice: Videograf, 2004.

SFJP — St. Skorupka. Słownik frazeologiczny języka polskiego. T. I–II. Warszawa: Wiedza Powszechna, 1993.

SMITK — W. Kopaliński. Słownik mitów i tradycji kultury. Warszawa: Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy, 1985.

Sz — Słownik języka polskiego, red. M. Szymczak. T. I–III. Warszawa: PWN, 1988–1989.

TBe — Terminų bankas. Prieiga per internetą: http://terminai.vlkk.lt/ [2020–04–15].

WSF — Wielki słownik frazeologiczny PWN z przysłowiami, A. Kłosińska, E. Sobol, A. Stankiewicz (red.), Warszawa: PWN, 2005.

WSJPe — P. Żmigrodzki. Wielki słownik języka polskiego. Wersja elektroniczna: http://www.wsjp.pl/ [2020–04–15].

References

BERLIN, B., KAY, P., 1969. Basic Color Terms. Their Universality and Evolution. Berkeley: University of California Press.

PIETRZAK-PORWISZ, G., 2006. Semantyka bieli w języku polskim i szwedzkim. Studia Linguistica Universitatis Iagellonicae Cracoviensis 123, 135–154.

TEODOROWICZ-HELLMAN, E., 1997. Biały w języku polskim i vit w języku szwedzkim. Analiza wstępna. In: Nilsson, B., Teodorowicz-Hellman, E. (red.). Nazwy barw i wymiarów. Colour and Measure Terms. Stockholm: University of Stockholm, 34–41.

TOKARSKI, R., 1995 (2004). Semantyka barw we współczesnej polszczyźnie. Lublin: Wydawnictwo UMSC.

TOKARSKI, R., 1997. Regularny i nieregularny rozwój konotacji semantycznych nazw barw. In: B. Nilsson, E. Teodorowicz-Hellman (red.). Nazwy barw i wymiarów. Colour and Measure Terms. Stockholm: University of Stockholm, 63–74.

WASZAKOWA, K., 2000a. Podstawowe nazwy barw i ich prototypowe odniesienia. Metodologia opisu porównawczego. In: R. Grzegorczykowa, K. Waszakowa (red.). Studia z semantyki porównawczej. Nazwy barw. Nazwy wymiarów. Predykaty mentalne. Część I. Warszawa: Wyd. Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego, 17–28.

WASZAKOWA, K., 2000b. Struktura znaczeniowa podstawowych nazw barw. Założenia opisu porównawczego. In: R. Grzegorczykowa, K. Waszakowa (red.). Studia z semantyki porównawczej. Nazwy barw. Nazwy wymiarów. Predykaty mentalne. Część I. Warszawa: Wyd. Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego, 59–72.

WIERZBICKA, A., 1999. Znaczenie nazw kolorów i uniwersalia widzenia. In: J. Bartmiński (red.) Język –— umysł — kultura. Warszawa: PWN, 405–449.

Viktorija Ušinskienė, PhD (Humanities), Assoc. Prof. of the Centre for Polish Studies of Vilnius University.

Viktorija Ušinskienė, humanitarinių mokslų daktarė, Vilniaus universiteto Polonistikos centro docentė.

Viktorija Ušinskienė, doktor nauk humanistycznych, docent w Centrum Polonistycznym Uniwersytetu Wileńskiego.

1 Tokarski [1995] examines color names by considering their prototypes and connotations, and taking into account both systemic and textual (i.e. individual) connotations. Waszakowa’s [2000a, 2000b] aim is to identify (through the analysis of the words connectivity) the semantic spheres to which the names of colors are referred to, as well as to compare the conceptualization of a given color range in different languages.

2 A. Wierzbickа as the prototype of the white color recognizes DAY, which in its turn is associated primarily with LIGHT and BRIGHTNESS, thus, the differentiation of these concepts does not seem reasonable [Wierzbicka 1999, 421].