Slavistica Vilnensis ISSN 2351-6895 eISSN 2424-6115

2022, vol. 67(1), pp. 99–115 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/SlavViln.2022.67(1).86

Spoon, Knife and Fork across Slovenian Dialects

Januška Gostenčnik

ZRC SAZU Fran Ramovš Institute of the Slovenian Language, Ljubljana, Slovenia

E-mail: januska.gostencnik@zrc-sazu.si

ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5967-0920

Mojca Kumin Horvat

ZRC SAZU Fran Ramovš Institute of the Slovenian Language, Ljubljana, Slovenia

E-mail: mojca.horvat@zrc-sazu.si

ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3235-4909

The article is an adapted and translated version of the article Slovenska narečna poimenovanja za žlico, nož in vilice, published in the Slovenski jezik / Slovene Linguistic Studies journal, no. 1/2021.

Abstract. The article presents Slovenian dialect names for cutlery used in eating or preparing food – spoon, knife and fork, from a geolinguistic, word-formational as well as etymological and semantic-motivational perspectives. The ethnological framework serves in particular to present the reasons for the (non-)borrowing of lexemes. It turns out that the terms for spoon and knife are not diverse from the point of view of borrowing, since the denotata have been in use in the Slovenian language area for a relatively long time. The fork was introduced relatively late as part of cutlery, so the most common name for it is a word-formational diminutive, and a high level of lexeme borrowing is observed in contact with the non-Slavic language area. The name for knife demonstrates word-formational diversity due to different uses in the past. The lexemes nožič, vilice and razsoška or plural razsoške have undergone a word-formational change, as they have kept their structural suffixes, but these do not (or rather, no longer) carry word-formational meaning; they are thus tautological derivations. The lexemes nož and pošada display a semantic change, as the meaning of both has narrowed in the hypernym → hyponym direction.

Keywords: Slovenian dialects, Slovenian linguistic atlas, cutlery, word-formation, geolinguistics, comparative Slavic linguistics

Ложка, нож и вилка в словенских диалектах

Аннотация: В статье рассматриваются словенские диалектные названия столовых приборов, используемых для приема или приготовления пищи – ложка, нож и вилка с точки зрения геолингвистики, словообразования, этимологии, семантической мотивации. Этнологическиe рамки облегчают, в частности, установление причин (не)заимствования рассматриваемых лексем. Термины, обозначающие ложку и нож, при заимствовании не различаются, так как их денотаты используются в словенском языковом пространстве уже довольно давно. Вилка, напротив, появилась относительно поздно, поэтому наиболее распространенное название для нее — словообразовательный диминутив; на границах с неславянским языковым пространством часто наблюдаются неславянские заимствования. Диалектные названия ножа демонстрируют словообразовательное разнообразие из-за использования этого предмета в прошлом в самых разных целях.

Ключевые слова: словенские диалекты, Словенский лингвистический атлас, столовыe приборы, словообразование, геолингвистика, сравнительное славянское языкознание

Šaukštas, peilis ir šakutė slovėnų kalbos tarmėse

Santrauka: Straipsnyje aptariami slovėnų dialektiniai valgant naudojamų stalo įrankių – šaukšto, peilio ir šakutės – pavadinimai geolingvistikos, žodžių darybos, etimologijos, semantinės motyvacijos požiūriu. Etnologinė struktūra ypač palengvina nagrinėjamų leksemų skolinimosi (ne)priežasčių nustatymą. Pasiskolinti šaukštą ir peilį žymintys terminai nesiskiria, nes slovėnų kalbos erdvėje jie vartojami gana seniai. Atvirkščiai, šakutė atsirado palyginti vėlai, todėl dažniausias jos pavadinimas yra mažybiniai vediniai: slovėnų kalbos ir neslavų kalbų kontaktų erdvėje dažnai vyksta neslaviškų pavadinimų skolinimas. Tarminiai peilio pavadinimai rodo išvestinę įvairovę dėl šio objekto naudojimo įvairiais tikslais praeityje.

Reikšminiai žodžiai: slovėnų kalbos tarmės, Slovėnų kalbos atlasas, stalo įrankiai, žodžių daryba, geolingvistika, lyginamoji slavų kalbotyra

Received: 19.01.2022. Accepted: 13.06.2022.

Copyright © 2022 Januška Gostenčnik, Mojca Kumin Horvat. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

1 Introduction1

Slovenian dialectal materials for the names of three basic pieces of cutlery — spoon, knife and fork — are at the core of the present discussion. Materials from the entire Slavic linguistic area have been used to facilitate orientation within the Slovenian language.

The study has aimed to answer the question what the dialectal names of individual pieces of cutlery under consideration have in common. Specifically, the interest has been whether they share any common either etymological, ethnological or typological characteristics.

Language and its words do not live separately from human life and activity. On the contrary, just as the (historical, societal and economic) situation of people or a given linguistic community and consequently their reality and physical world change, so do new words and meanings emerge or are borrowed from a territorially (non-) neighbouring language community when the need arises. Implements used in eating or preparing food, i.e., pieces of cutlery — spoon, knife and fork — are telling proofs of this.

However, the present study has revealed that something that is so tightly interconnected today does not share a common historical path: spoon, knife and fork reached their common hypernym, cutlery, through different routes of development. Familiarisation with these routes requires a relevant (dialectal) source of material, a word-formational and etymological analysis of the material and the identification of the semantic motivation of each lexeme’s emergence. The geolinguistic interpretation plays the role of displaying the collected and analysed materials more illustratively and points to the distribution and purpose of the named object as the result of different cultural influences. All this belongs to the field of linguistics, which, however, can present the history of individual parts of (contemporary) cutlery as tangible cultural heritage much better when considered in conjunction with ethnology.

2 Sources

The main source of materials for the study has been the Slovenian Linguistic Atlas (hereafter SLA) (https://sla.zrc-sazu.si/#v), but other Slavic languages have been taken into consideration as well — the Slavic Linguistic Atlas or Общеславянский лингвистический атлас (OLA) (www.slavatlas.org; http://ola.zrc-sazu.si/index.htm) has thus been a complementary source. Dialectal materials collected specifically for this study serve to shed light on the wider context.

2.1 SLA

SLA, which is being made at the Fran Ramovš Institute of the Slovenian Language at the SAZU Research Centre, was designed in 1934 by Fran Ramovš, a Slovenian linguist who followed the example of other European nations that had published their first linguistic atlases. Ramovš [1935, 11] was convinced that Slovenian linguistics needed a linguistic atlas covering the entire dialect diversification of the Slovenian language.2 This idea was developed further to become the basic project of Slovenian dialectology.

The SLA network includes 417 data points3 or local dialects, of which 78 are outside the state borders of Slovenia (41 data points in Austria, 2 in Hungary, 7 in Croatia and 28 in Italy). The questionnaire for SLA consists of 870 numbered questions or over 3000 in total when combined with supplementary questions.4

In the SLA (the first volume was published in 2011, the second in 2016, and the third is in the making),5 dialectal materials are published, spatially displayed on so-called word maps and explained in structurally uniform commentaries and published in indices. The second volume of SLA, i.e., Slovenski lingvistični atlas 2 — Kmetija (Slovenian Linguistic Atlas 2 — The Farm), is lexical, word-formational6 and sporadically semantical and presents a linguistically interpreted and ethnologically interesting physical world from all regions in the Slovenian language area.

Dialectal lexis belonging to the semantic field “farmhouse, farm, selected farm work” also includes expressions naming parts of cutlery or implements that are now used in preparing or eating food – spoon [Gostenčnik in SLA 2.1, 209, SLA 2.2, 366]7, knife [Kumin Horvat in SLA 2.1, 128−129, SLA 2.2, 236−237]8 and fork [Gostenčnik in SLA 2.1, 126−127, SLA 2.2, 234−235].9

2.2 OLA

OLA is a Slavic linguistic atlas involving linguists from all Slavic language communities. Work on OLA has been carried out since 1961 within the International Commission for the Compilation of the Slavic Linguistic Atlas based at the Russian Academy of Sciences in Moscow under the International Committee of Slavists. The main aim is the historical-comparative and synchronic-typological study of Slavic dialects. The network of localities comprises approximately 850 data points in total, including 25 Slovenian ones (of which 3 are in Italy, 3 are in Austria, and 1 is in Hungary).

3 Theoretical-methodological framework

3.1 Linguistic-theoretical basis

In terms of origin [based on Snoj 2016, 14–15], words are categorised into three main groups: 1. words that have arisen as part of continuous linguistic development, 2. words that have been borrowed from foreign languages and 3. imitative words. The collected materials mostly belong to the first and partly to the second group, while there are no imitative words.

As shown by research [Haspelmath, Tadmor 2009], words from some semantic fields are more susceptible to borrowing than others. According to the borrowability table, names for spoon, knife and fork are on the list of borrowing-resistant words included in semantic field 5, Food and drink (out of 24 semantic fields) (2009), or in semantic field 7, Food and drink [Haspelmath, Tadmor, Taylor 2010], which allows the assumption that their names in different languages are more likely to have arisen as part of continuous linguistic development and are less likely borrowed.

3.1.1 Inherited Slavic materials. The interpretation of inherited Slavic materials, i.e. words that have arisen as part of continuous linguistic development, is based on historical lexicology. The etymological explanation of materials presented here is based first on a word-formational analysis of the lexeme, which is initially used to ascertain the meanings and functions of individual morphemes, and then the denotative meaning of the root and the function of the other non-final morphemes are added together to form the structural meaning, and by knowing the physical world, i.e., what is named, the motivation that gave rise to the lexical meaning is explained [Furlan 2013, 21].

Within synchronically provided materials, however, there are frequent cases of lexemes with word-formational suffixes that no longer bear their word-formational meaning. This article thus uses the phrase tautological derivation (Polish derywat tautologiczny), which has been adopted from Polish linguistics [Kowalska 2011, 127]. In Slovenian word-formation, this phrase fills a terminological void for naming [Kumin Horvat 2013, 39 footnote 8] derived words whose denotative meaning is the same as the denotative meaning of the word-formation base, as the suffix does not provide any word-formational-semantic modification but is merely the carrier of a structural function [Kumin Horvat 2013, 39].

As regards the presence and frequency of individual structural types, it has been found that phrasal names are much more common in more peripheral dialects, while more word-formational differentiation has been noted in the central dialects for the lexemes belonging to the studied semantic sets. [Kumin Horvat 2012, 223]

In lexemes that are unmotivated in terms of word-formation, the central interest lies in the potential semantic change — a phenomenon in which, on a time axis, a given lexeme (in addition to a likely phonetic change) changes meaning, but not form. The lexeme thus changes at the (phonetic and) semantic, but not the formal level [Šekli 2011, 26]. Within the collected materials, there are also lexemes that have undergone a so-called narrowing of meaning. This is a semantic change in which a lexeme’s meaning becomes less extensive and more intensive, or in which the classifying semantic feature is kept and differentiating semantic features are acquired in terms of intensity [Šekli 2011, 26].

3.1.2 Borrowed lexis. The analysis of lexemes borrowed from foreign languages is based on the identification of borrowed elements from territorially neighbouring geolects and the possible added Slavic or Slovenian word-formational suffix.

Borrowed elements are considered to comprise lexemes that have been borrowed into Slovenian and then adapted in form (or not) and lexemes that have served as word-formation bases to form new lexemes in Slovenian. Only direct sources (proximate origin) are listed as foreign-language sources of a Slovenian dialectal lexeme, specifically in the temporal and stylistic variant of the foreign language that has been reconstructed as the likeliest source in light of the phonetic form of the Slovenian lexeme [Šekli in SLA 2.2, 56].

3.1.3 Geolinguistic presentation. Methodologically speaking, the geolinguistic presentation of dialectal materials is mostly based on the spatial distribution of individual lexemes, which is displayed on linguistic maps. It is traditional in principle and displays the synchronic word-formational or lexemic situation in the area of the Slovenian language system.

It builds upon the maps from the Slovenian Linguistic Atlas 2, but these have been visually10 adapted to suit the needs of the present discussion.

3.2 Ethnological-historical framework

The earliest element of cutlery is the spoon; žlica is attested as a Slovenian lexeme in 16th-century sources. It was used for the consumption of all types of food, not only liquids. Spoons were originally made of wood, later of metal as well [SEL 2004, 191].

Ethnological discoveries describe the knife as one of the earliest human inventions, which was first used as a tool but has developed into a piece of cutlery between prehistory and modern times.

The fork gained a foothold in Slovenia only in the second half of the 19th century, first in cities and towns, then in the countryside as well. In certain higher social strata, the fork had been used much earlier, presumably in the 16th century [Hazler in SLA 2.2, 235].

As regards the development of the eating culture and the related use of cutlery, Vilko Novak (1960, 164) notes that a major development in the manner of eating took place when the family moved from the fireplace in the smokehouse, where they had eaten from a common bowl and reached for many foods with their bare hands, to a table in the hiša — ‘main room’, where they still ate from a common bowl in a great many cases and used only spoons, but plates for every member with individual cutlery had also been widely adopted.

4 Cutlery across Slovenian dialects

The name for spoon features no lexemic diversity, both in terms of origin and word- formation. The names for knife are not diverse in terms of origin, but there is a high level of word-formational differentiation. The names for fork feature the highest level of borrowing, which raises two questions – the first relates to the semantic motivation of the non-borrowed lexeme, and the second to the reasons for the relatively high number of borrowed lexemes.

4.1 Spoon

4.1.1 Geolinguistic presentation

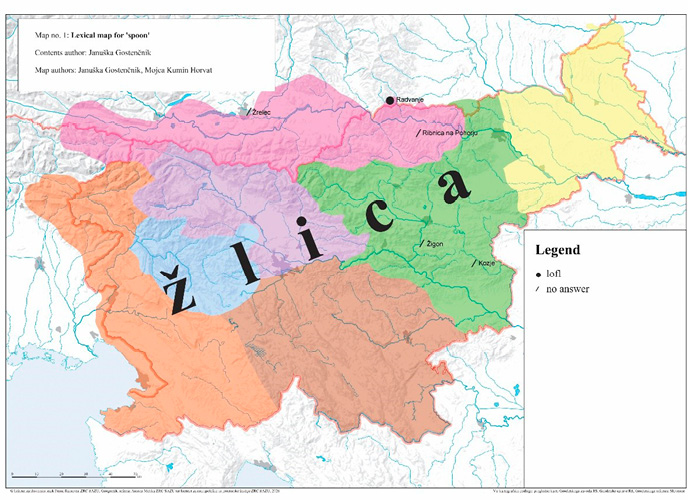

Figure 1: Lexical map for ‘spoon’

4.1.2 Analysis. Dialectal names for spoon, i.e., ‘a utensil with a long handle and oval concave part for putting (food) in one’s mouth’, are not diverse in terms of lexemes and word-formation; the (almost) only lexeme in the SLA materials is žlica ‘spoon’ (< PSl. *lъž-ic-a ← unattested *lъž-i) of Slavic origin. Only in SLA T415 (Radvanje — Rothwein), there is a one-off appearance of the Germanism lofl, which originates in the German Löffel ‘spoon’.

In her Istrian-Slovenian materials, Suzana Todorović lists the lexeme kučar (< Triestine Italian cuciar ‘spoon’ [Doria 1987, 189]) and its variant kučaro [Todorović 2020, 640], which do not appear in the SLA materials, in addition to žlica.

4.1.3 Slavic materials. A great uniformity of word roots is characteristic of the entire Slavic language area; in terms of word-formation, all the lexemes are diminutives. Compare:11 Croatian žlica, dialectal Serbian làžica, ložȉca, Macedonian лажица, Bulgarian лъжица, Czech lžíce, Upper Sorbian łžica, Lower Sorbian łžyca, Old Russian лъжица, Polabian låzaic12 (← *lъž-ic-); Slovak lyžica (← *lyž-ic-a); Polish łyżka (← *lyž-ьk-a); dialectal Czech ležka, Russian ложка, Belarusian лыжка, Ukrainian ложка (← *lъž-ьk-a) [OLA 6, 141, Snoj in Bezlaj 2005, 466].

Only in the Bosnian and Serbian standard languages, there is the borrowed lexeme kašika ‘spoon’ (< *(kašik)-a ← Turkish kaşık). This lexeme also predominates in Serbian dialects, such as OLA T082 Велика Крушевица (Velika Kruševica) kaʹšika, and rarely coexists on equal terms with the Slavic synonym žlica, such as in T081 Дренча (Drenča) loʹžica (← *lъž-ic-a), kaʹšika. Within Bosnian dialects, kašika is the only attested lexeme; only in the local dialect of OLA T038 Лохово (Lohovo) has žlica already become part of the passive vocabulary — kášika, archaic žlìca. The Turkism kašika appears as an exception in some Croatian local dialects as well, namely in OLA T150 Pogan (Pogány) in Hungary as kasìka [OLA 6, 140].

4.2 Knife

4.2.1 Geolinguistic presentation

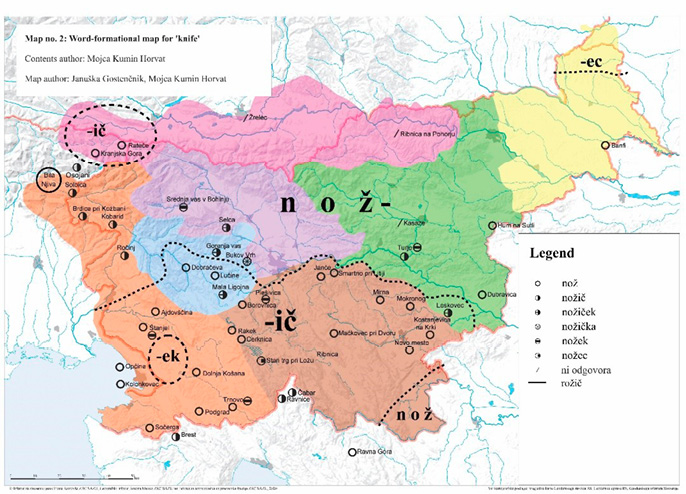

Figure 2: Word-formational map for ‘knife’

4.2.2 Analysis. Across the SLA materials, there are seven different lexemes for the meaning ‘utensil for cutting consisting of a blade and handle’ in Slovenian dialects, six of which belong to the word family with the root nož-, while the seventh name, rožič ‘knife’, is not related to the others at the root level. In her Istrian-Slovenian materials, Suzana Todorović lists the lexemes pošada ‘knife’ [Todorović, Filipi 2017, 55–56] and kortel ‘knife’ [Todorović 2020, 639], which do not appear in the SLA materials, in addition to nožič ‘nož’.

As regards geographical distribution, the listed names are recorded in large or small continuous areas. The nož lexeme, which is also the standard name for the denotatum in question, covers the widest area; the derived word nožič forms the second widest area; the derived words nožek and nožec are recorded in more peripheral dialects, and nožiček only in four local dialects as a variant name; the derived word nožička appears only once.

Thus, based on their distribution in the dialects (and in the standard language), the studied lexemes can be treated as pan-Slovenian or narrowly dialectal. In dialects, the pan-Slovenian lexeme nož, also present in the standard language as the neutral name, is recorded in a wide area, which extends from the Ter, Nadiža and Brda dialects and the northern part of the Karst dialect in the Littoral dialect group as well as the Tolmin and Cerkno dialects of the Rovte dialect group in the west and then fully encompasses the Upper Carniolan, Carinthian (with the exception of the Zilja dialect), Styrian (with the exception of certain local dialects of Posavje) and Pannonian dialect groups (with the exception of the northern part of the Prekmurje dialect).

The second most prevalent lexeme is nožič ‘knife’, which has a diminutive meaning in the standard language but an unmarked meaning in dialects; based on this standard and dialectal distinction in meaning, it can be defined as a widespread lexeme. It has been recorded in a wide area that extends from the southern part of the Karst dialect as well as the entire Notranjska and Istrian dialects in the Littoral dialect group and then (with the exception of the Tolmin and Cerkno dialects) fully encompasses the Rovte and Lower Carniolan dialect groups (excluding the Southern Bela Krajina dialect), also appearing in a small area of the Zilja dialect in the Carinthian dialect group.

In addition to the pan-Slovenian and broad dialectal lexemes, the materials for nož ‘knife’ also include records of locally spread names, namely nožec ‘knife’, recorded only in the northern part of the Prekmurje dialect, and nožek ‘knife’, recorded within an area of the Notranjska dialect and individually in the Upper Carniolan local dialect of Srednja vas v Bohinju (SV) and the Lower Carniolan local dialect of Plešivica (Pl). Both lexemes are treated as diminutives in the standard language but definitely as neutral names in dialects.

The lexemes nožiček and nožička always appear as variants of the lexeme nož or nožič in the materials, which suggests their word-formational meaning is diminutive in dialects as well.

As noted by Todorović and Filipi, the lexeme pošada is recorded in continuous areas in three local Istrian dialects. [Todorović, Filipi 2017, 55].

The name rožič, which is the only recorded name in two Resian data points, forms the smallest area.

The dialectal names for the meaning ‘utensil for cutting consisting of a blade and handle’ have all arisen as part of continuous linguistic development; both the derived words with the root nož- (*nož-ь ‘that which pricks, stabs; knife’: nožič < *nož-it́-ь; nožiček < *nož-it́-ьk-ъ; nožička < *nož-it́-ьk-a; nožek < *nož-ьk-ъ; nožec < *nož-ьc-ь) and the lexeme rožič (*rož-it́-ь ← *rog-ъ ‘horn’) have been formed out of Proto-Slavic word-formational precursors.

Thus, no borrowed names are recorded in the SLA materials for Slovenian dialects, but the Romance borrowed names kortel ‘knife’ (< Triestine Italian cortel ‘knife’ [Doria 1987, 176]) and pošada (< Istrian Venetian posàda ‘cutlery’ [Manzini – Rocchi 1995, 196]) are listed for this meaning by Todorović and Filipi [2017, 2020]. With pošada, a narrowing of the name’s original meaning can be observed: ‘cutlery’ → ‘piece of cutlery, i.e. knife’.13

From the word-formation point of view, it appears at first glance that all the derived words — nožič, nožiček, nožička, nožek and nožec — are still both word-formational and semantic diminutives, as they were originally, but that is not the case. Data on the meaning of the nožič lexeme, such as for the local dialects of Bistrica na Zilji/Feistritz an der Gail, Blače/Vorderberg, Brdo pri Šmohorju/Egg bei Hermagor, Ricmanje/San Guiseppe della Chiusa, where this word means ‘kitchen knife’ and ‘ordinary knife’, clearly demonstrate these are no longer semantic diminutives, but only word-formational diminutives. This finding is corroborated by data from:

a) some dialect dictionaries, e.g., Kostelski slovar [Gregorič 2015, accessible at fran.si], where nožič is a ‘utensil for cutting consisting of a blade and handle’, while nožiček and nožičkec are true diminutives; Rječnik brodmoravičkog govora [Crnković, manuscript], where nožič is ‘knife’, and nožiček is ‘small knife’; the dictionary of the Haloze dialect (Belanski narečni govor), where nuž is ‘knife’, and nužek is a ‘double-handled knife for woodworking, wheelwright’s draw knife’ [Prašnički 2016, 180];

b) some examinations of local dialects in bachelor theses, where the nožič lexeme is recorded as a neutral name (e.g., in the Notranjska local dialect of Planina pri Ajdovščini [Bajec 2012], in the Karst local dialect of Ozeljan [Bučinel 2001] and Dornberk [Kavčič 2019], in the Istrian dialect and the Eastern Lower Carniolan subdialect of the Lower Carniolan dialect [Špiler 2016]).

The lexemes nož and nožič appear simultaneously, as synonyms, only in one data point of the SLA collection, i.e., T126 Sočerga. The synonymity and neutrality of the two lexemes are corroborated by the materials for the Istrian data point of Padna in SDLA-SI I for question V367 ‘kitchen knife’ ʹnužić/ʹnuoš [Cossutta 2005, 432] and materials of the Črni Vrh dialect dictionary [Tominec 1964, 141], i.e., nož and nožič.

The derived words nožič, nožek and nožec are thus so-called tautological derivations from the word-formation point of view, while the derived words nožiček and nožička are semantic diminutives.

4.2.3 Slavic materials. The non-diversity of lexemes and roots in general in the materials for nož can be observed across the entire Slavic materials, as all standard languages use the same lexeme, nož, in phonetic variants: Upper Sorbian nóž, Lower Sorbian nož, Polabian nüž, Polish nóż, Czech nůž, Slovak nóž, Bulgarian нож, Macedonian нож, Russian нож, Ukrainian нiж, Belarusian нож, Croatian nož, Serbian nož. [Snoj in Bezlaj 1982, 229]

4.3 Fork

4.3.1 Geolinguistic presentation

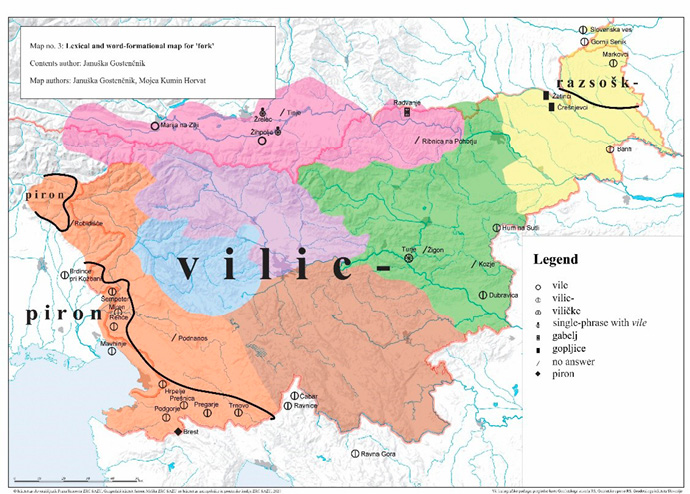

Figure 3: Lexical and word-formational map for ‘fork’

4.3.2 Analysis. The Slavic vilice ‘fork’ or its singular variant vilica is the most commonly attested lexeme for the meaning ‘utensil consisting of prongs and a handle for sticking pieces of food on’ in Slovenian dialects; this name extends across almost the entire Slovenian language area. Both the plural and singular forms appear as the answer in Slovenian dialects, leading to the display of both with the abstracted form vilic- on the lexical and word-formational map for ‘fork’. For example, the singular form is recorded in data points T032 Djekše — Diex, T033 Kneža — Grafenbach, T036 Rinkole — Rinkolach, T038 Vidra vas — Wiederndorf, T086 Kojsko, T089 Ročinj, T090 Avče, T092 Kal nad Kanalom, T094 Podlešče, T104 Branik, T198 Zgornje Gorje, T205 Zgornje Jezersko, T286 Stari trg ob Kolpi, T308 Velika Dolina, T358 Pivola, T375 Gibina, T384 Žetale, T392 Gomilica, T393 Nedelica, T403 Markovci, T404 Gornji Senik — Felsőszölnök, T407 Banfi, T408 Hum, T409 Dubravica, T410 Čabar, T412 Ravna Gora. Within the same word family, there are also single appearances of the lexeme viličke ‘fork’ and the phrases ta manjše vile ‘fork’ and majhne vile ‘fork’ in the Rož dialect.

The borrowed lexeme piron ‘fork’, a Romance word found in the Littoral dialect group14, and the lexeme razsoška ‘fork’ or plural razsoške ‘fork’ in the Prekmurje dialect are next in terms of frequency.

As regards Germanisms, the lexeme gopljice forms a small area in the Pannonian dialect group in the north-east, at the contact of the Slovenske gorice and Prekmurje dialects, while the lexeme gabelj appears only once in the North Pohorje-Remšnik dialect.

The names vilice (vilic- < *vidl-ic-ę/*vidl-ic-a ← *vidl-ę ‘vile’ according to SLA 2.2, 234) and razsošk- (< *orz-soš-ьk-a/-ę ← *orz-sox-a ‘tree fork’ ← *orz- [prefix meaning ‘apart’] + *sox-a ‘branch’) are inherited Slavic lexemes. Both arose with the same semantic motivation, which was the meaning ‘that which is branched’, i.e., vile ‘(pitch)fork’ or razsohe, which means ‘hay fork’ in the contemporary local dialect of eastern Styria [Furlan in Be III, 160].

The Romance name piron has been borrowed from Friulian piron or Venetian Italian piron, which originates from the Greek word περόνη ‘pin’ < ‘object used for piercing’ [Furlan in Bezlaj 1995, 40]. The gabelj lexeme and the root of the gopljice lexeme have been borrowed from the Bavarian variant of the German language (cf. German Gabel ‘fork’).

The most frequently attested and standard lexeme vilice ← vile is a word-formational diminutive, but not (or rather, no longer) a semantic diminutive. Razsošk- ← razsoha is also a word-formational diminutive. The underived lexeme vile appears only in two attested phrases (majhne/manjše vile). In terms of syntactic word-formation, the phrases ta manjše vile ‘fork’ (T020 Žihpolje — Maria Rain) and majhne vile ‘fork’ (T021 Žrelec — Ebenthal) are more primitive compared to the diminutive with the -ica suffix.15 The diminutive gopljice (pl.), whose word-formational precursor is the Germanism goplj-, has been derived using the Slovenian suffix -ica.

4.3.3 Slavic materials. Other standard Slavic languages display the same word-formational motivation, i.e., a word-formational diminutive of the precursor *vidl-. Compare: Polish widelec (instead of *widlec), Belarusian відэльцы (← *vidl- + *-ьc-); Czech vidlice, Slovak vidlica, Upper Sorbian widlicy, Lower Sorbian widlice, Kashubian v́idlëca, Macedonian/Bulgarian вилица, Croatian vilica (← *vidl- + *-ic-); Serbian viljuška (← *vidl- + *-ux- + *-ьka); Russian вилки, Ukrainian виделки (← *vidl- + *-ьk-) [Snoj in Bezlaj 2005, 317].

5 Names for cutlery in Slovenian dialects

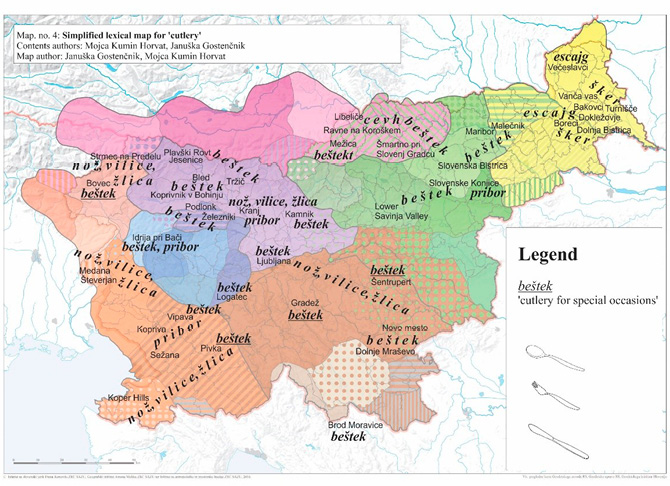

As the SLA material collection does not include a question for ‘cutlery’, the materials for this have been acquired from available dialect dictionaries, selected bachelor theses and through a short survey. The answers obtained have been standardised in form and can be categorised in six groups:

1. beštek < German Besteck ‘cutlery’ —

a) ‘cutlery for everyday use’: Idrija pri Bači (arch.), Bled, Tržič, Podlonk, Koprivnik v Bohinju, Kamnik, Železniki, Plavški Rovt, Jesenice, Ljubljana, Slovenske Konjice, Slovenska Bistrica, Lower Savinja Valley, Malečnik, Maribor, Novo mesto, Dolnje Mraševo, Brod Moravice, Vipava, Logatec, Ravne na Koroškem, Libeliče and phonetical variant beštekt in Mežica;

b) ‘cutlery for special occasions’: Bovec, Pivka, Gradež, Šentrupert,

2. šker < OHG giskirri ‘dish, device’, MHG geschirre ‘dish, device’ [Furlan in Bezlaj 2005, 54] — Dolnja Bistrica, Boreci, Vanča vas, Turnišče;

3. escajg < German Esszeug ‘cutlery’ — Dokležovje, Bakovci, Večeslavci;

4. pribor < Czech příbor ‘cutlery, dishware’ ← Czeczh přebrat, přebírat ‘to sort, to select’ — Idrija pri Bači, Kranj, Kopriva, Sežana, Vipava, Slovenske Konjice;

5. cevh < MHG ziuc, ziug ‘hand tools’, German Zeug ‘things’ [Bezlaj 1977, 63] — Ravne na Koroškem, Libeliče;

6. nož, žlica, vilice ‘cutlery’ (no hypernym) — Kranj, Ljubljana, Pivka, Koper Hills, Števerjan, Medana, Bovec, Strmec na Predelu, Gradež, Šentrupert.

The dialectal materials suggest that in Slovenian dialects hypernyms for ‘cutlery’ were not in general use as the phrase noži, žlica, vilice is widely spread. The most frequent borrowed lexem beštek can have the meaning ‘cutlery for everyday use’, but often coexists with the phrase noži, žlica, vilice then having the meaning ‘cutlery for special occasions’, which suggests a later borrowing. The lexemes escajg and šker are heard in the dialects of the Pannonian dialect group, cevh in the Carinthian dialect group. Literary lexem pribor is dispersed across the wider Slovenian area. It was accepted into Slovenian literary language from Czech only in the 19th century.

Figure 4: Simplified lexical map for ‘cutlery’

6 Conclusion

This article discusses dialectal lexemes naming three objects with similar, yet different culturological/ethnographic backgrounds. In examining the origin of each lexeme, the question of its connection to the origin of the denotatum itself has thus been explored. The situation in Slovenian dialects has also been clarified and put into context with wider Slavic materials.

Based on the dialectal materials, it can be concluded that the lexemes nožič ‘knife’, vilice and razsoška ‘fork’ or plural razsoške have undergone a word-formational change, as they have kept their structural suffixes, but these do not (or rather, no longer) carry word-formational meaning; they are thus tautological derivations. The lexemes nož ‘knife’ and pošada ‘knife’ display a semantic change, as the meaning of both has narrowed in the hypernym → hyponym direction.

Based on findings from ethnological literature, the following chronology of the emergence and use of cutlery items can be outlined: 1) the knife and spoon are the oldest implements used for eating; when it appeared, the knife was used by the head of the family to cut big pieces of food, meat, bread [Novak 1964]; the food was eaten with the hands or spoon; 2) the fork is a newer piece of cutlery; its name in the Slovenian area fits two types: a) the name is a lexeme borrowed from neighbouring languages (in the Littoral dialect group and individually in the Carinthian and Pannonian groups); b) the name is taken from an already-known similar object, i.e. vile ‘farm tool’, razsoške ‘farm tool’ (in most dialects); 3) the table knife for each individual at the dinner table has appeared most recently and is thus the newest element of cutlery.

Bibliography

BAJEC, N., 2012. Kuhinjsko izrazje na Planini pri Ajdovščini: bachelor thesis. Ljubljana: Filozofska fakulteta, Univerza v Ljubljani. Mentor: Vera Smole.

BEZLAJ, F., 1977. Etimološki slovar slovenskega jezika I: A–J. Ljubljana: published for SAZU, Inštitut za slovenski jezik by Mladinska knjiga.

BEZLAJ, F., 2005. Etimološki slovar slovenskega jezika IV: Š–Ž, entry authors: France Bezlaj, Marko Snoj and Metka Furlan, editors: Marko Snoj and Metka Furlan. Ljubljana: published for SAZU – Znanstvenoraziskovalni center, Inštitut za slovenski jezik, Etimološko-onomastična sekcija – by Založba ZRC.

BUČINEL, M., 2001. Slovar kuharske terminologije v Ozeljanu: bachelor thesis. Ljubljana: Filozofska fakulteta, Univerza v Ljubljani. Mentor: Vera Smole.

CRNKOVIĆ, V. Rječnik brodmoravičkog govora. Forthcoming.

FURLAN, M., 2013. Novi etimološki slovar slovenskega jezika: Poskusni zvezek. Ljubljana: Založba ZRC.

GOSTENČNIK, J., KUMIN HORVAT, M., 2021. Slovenska narečna poimenovanja za žlico, nož in vilice, Slovenski jezik / Slovene Linguistic Studies, 13(2021). 21–40. https://doi.org/10.3986/sjsls.13.1.02

GREGORIČ, J., 2015. Kostelski slovar, www.fran.si, accessed 11.11.2020.

KOWALSKA, A., 2011. Gwary dziś: apelatywne nazwy miejsc w dialektach polskich: derywacja sufiksalna. Poznań: Wydawnictwo Poznańskiego Towarzystwa Przyjaciół Nauk.

KAVČIČ, J., 2019. Slovar govora kraja Dornberk: master thesis. Koper: Fakulteta za humanistične študije, Univerza na Primorskem. Mentor: Jožica Škofic.

KUMIN HORVAT, M., 2013. Narečne tvorjenke s priponskim obrazilom -ica iz pomenskega

polja »človek« (po gradivu za SLA 1). In WEISS, P. (ed.). Jezikoslovni zapiski: zbornik Inštituta za slovenski jezik Frana Ramovša, 19, no. 2, = Dialektološki razgledi, 33–57.

KUMIN HORVAT, M., 2018. Besedotvorni atlas slovenskih narečij. Ljubljana: ZRC SAZU, Založba ZRC.

MALNAR, S., 2008. Rječnik govora čabarskog kraja. Čabar: Matica hrvatska, Ogranak Čabar.

MANZINI, G., ROCCHI, L., 1995. Dizionario storico fraseologico etimologico del dialetto di Capodistria. Trieste: Università Popolare: Istituto Regionale per la Cultura Istriana, Rovigno: Centro di Ricerche Storiche.

NOVAK, V., 1960. Slovenska ljudska kultura: oris. Ljubljana: Državna založba Slovenije.

OLA = Obščeslavjanskij lingvističeskij atlas: serija leksiko-slovoobrazovatel’naja 6: Домашнее хозяйство и приготовление пищи, Москва: Международный комитет славистов комиссия общеславянского лингвистического атласа – Российская академия наук Институт русского языка им. В. В. Виноградова Институт славяноведения 2007, 140–143.

PRAŠNIČKI, M. et al., 2016. Belanski narečni govor. Cirkulane: Društvo za oživitev gradu Borl.

RAMOVŠ, F., 1935. Karta slovenskih narečij v priročni izdaji. Ljubljana: Akademska založba.

SEL = BAŠ, A., RAMŠAK, M., 2004. Slovenski etnološki leksikon. Ljubljana: Mladinska knjiga.

SDLA-SI = COSSUTTA, R., CREVATINO, F., 2005. Slovenski dialektološki leksikalni atlas slovenske Istre. Koper: Univerza na Primorskem, Znanstveno-raziskovalno središče, Založba Annales: Zgodovinsko društvo za južno Primorsko.

ŠEKLI, M., 2011. Neprevzeto besedje za sorodstvo v slovenščini z vidika zgodovinskega besedjeslovja. In SMOLE, V. (ed.). Družina v slovenskem jeziku, literaturi in kulturi: zbornik predavanj. Ljubljana: Znanstvena založba Filozofske fakultete, 21–28.

SLA 2.1 = ŠKOFIC J., GOSTENČNIK, J., HAZLER, V., HORVAT, M., JAKOP, T., JEŽOVNIK, J., KENDA-JEŽ, K., NARTNIK, V., SMOLE, V., ŠEKLI, M., ZULJAN KUMAR, D., (editors: ŠKOFIC, J., HORVAT, M., KENDA-JEŽ, K.). 2016. Slovenski lingvistični atlas 2: kmetija, 1: atlas. Ljubljana: Založba ZRC, ZRC SAZU (Jezikovni atlasi). Online edition at: www.fran.si.

SLA 2.2 = ŠKOFIC J., GOSTENČNIK, J., HAZLER, V., HORVAT, M., JAKOP, T., JEŽOVNIK, J., KENDA-JEŽ, K., NARTNIK, V., SMOLE, V., ŠEKLI, M., ZULJAN KUMAR, D., (editors: ŠKOFIC, J., ŠEKLI, M.). 2016. Slovenski lingvistični atlas 2: kmetija, 2: komentarji. Ljubljana: Založba ZRC, ZRC SAZU (Jezikovni atlasi). Online edition at: www.fran.si.

ŠPILER, M., 2016. Besedni atlas za posodo 1 (BAP1): bachelor thesis. Ljubljana: Filozofska fakulteta, Univerza v Ljubljani. Mentor: Vera Smole.

TADMOR, U., HASPELMATH, M., TAYLOR, B., 2009. Loanwords in the world’s languages: A comparative handbook. Berlin, New York: De Gruyter Mouton.

TADMOR, U., HASPELMATH, M., TAYLOR, B., 2010. Borrowability and the notion of basic vocabulary, Diachronica, 27(2). 226–246. https://doi.org/10.1075/dia.27.2.04tad

TODOROVIĆ, S., FILIPI, G., 2017. Etimologije izbranih aloglotizmov s področja kuhinje v slovenskih istrskih govorih, Croatica et Slavica Iadertina: časopis Odjela za kroatistiku i slavistiku, 13(1). 49–63.

TODOROVIĆ, S., 2020. Istrskobeneški jezikovni atlas severozahodne Istre 2: števniki in opisni pridevniki, čas in koledar, življenje, poroka in družina, hiša in posestvo. Koper: Libris, d. o. o., Italijanska unija, Osrednja knjižnica Srečka Vilharja Koper.

TOMINEC, I., 1964. Črnovrški dialekt. Ljubljana: Slovenska akademija znanosti in umetnosti.

Januška Gostenčnik, PhD, Assistant professor, Research Associate at the ZRC SAZU Fran Ramovš Institute of the Slovenian Language.

Янушка Гостенчник (Januška Gostenčnik), доцент, научный сотрудник Институт словенского языка имени Франа Рамовша, Научно-исследовательский центр Словенской Академии наук и искусств.

Januška Gostenčnik, docentė, Slovėnijos mokslų ir menų akademijos Slovėnų kalbos Frano Ramovšo instituto mokslo darbuotoja.

Mojca Kumin Horvat, PhD, Research Associate at the ZRC SAZU Fran Ramovš Institute of the Slovenian Language.

Мойца Кумин Хорват (Mojca Kumin Horvat), научный сотрудник Института словенского языка имени Франа Рамовша, Научно-исследовательский центр Словенской Академии наук и искусств.

Mojca Kumin Horvat, humanitarinių mokslų daktarė, Slovėnijos mokslų ir menų akademijos Slovėnų kalbos Frano Ramovšo instituto mokslo darbuotoja.

1 The article has been produced based on research results within the i-SLA – Interaktivni atlas slovenskih narečij (i-SLA – Interactive Atlas of Slovene Dialects) project (L6-2628, 1.9.2020–31.8.2023), co-financed by the Slovenian Research Agency under the P6-0038 programme (1.1.2004–31.12.2021).

2 A current map of Slovenian dialects is available at: https://www.fran.si/204/sla-slovenski-lingvisticni-atlas/datoteke/SLA_Karta-narecij.pdf.

3 The SLA network is available at: https://www.fran.si/203/sla-slovenski-lingvisticni-atlas-2/datoteke/SLA2_Atlas.pdf (page 13), and a list of localities is available at: https://www.fran.si/203/sla-slovenski-lingvisticni-atlas-2/datoteke/SLA2_Kraji.pdf.

4 The full questionnaire is available at: http://bos.zrc-sazu.si/c/Dial/Ponovne_SLA/P/03_1_Vprasalnica_STEV.pdf.

5 The first and second volumes are both freely accessible at the www.fran.si and https://sla.zrc-sazu.si/#v portals.

6 The maps are either lexical or lexical and word-formational; there are no purely word-formational maps.

7 The dialectal materials for spoon published in SLA 2 are available at: https://www.fran.si/Search/File2?dictionaryId=203&name=gradivo_karti__SLA_V151.01.pdf.

8 The dialectal materials for knife published in SLA 2 are available at: https://www.fran.si/Search/File2?dictionaryId=203&name=gradivo_karti__SLA_V153A.01.pdf.

9 The dialectal materials for fork published in SLA 2 are available at: https://www.fran.si/Search/File2?dictionaryId=203&name=gradivo_karti__SLA_V152.01.pdf.

10 Data on which dialect the local dialect belongs to have been added; the local dialect labels have been modified to replace the numerical labels with alphabetical ones; isoglosses and text lines have been added.

11 Unless otherwise stated, the examples provided are taken from standard languages.

12 Reconstruction according to ESSJA 16, 258.

13 A narrowed meaning is also displayed by pošada meaning ‘kitchen knife’ on the Chakavian island of Vrgada in northern Dalmatia [Furlan in Bezlaj III, 93].

14 The same is confirmed by Todorović (2017, 59−60) for Istrian and Chakavian data points.

15 In Slovenian dialects, this phenomenon has also been noted for the cultivated plants semantic field (Kumin Horvat 2018, 223).